Lorenzo Mango

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Approval Page for Graduate Thesis Or Project Gs-13

APPROVAL PAGE FOR GRADUATE THESIS OR PROJECT GS-13 SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF REQUIREMENTS FOR DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS AT CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, LOS ANGELES BY Dan Terrence Belzer Candidate Theatre Arts Field of Concentration TITLE: The Sound and Music of Ibsen APPROVED: Susan Mason, Ph.D. Faculty Member Signature David Connors, D.M.E. Faculty Member Signature Jane McKeever, M.F.A. Faculty Member Signature Peter McAllister, Ph.D. Department Chairperson Signature DATE: October 13, 2011 THE SOUND AND MUSIC OF IBSEN A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Music, Theatre, and Dance California State University, Los Angeles In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts By Dan Terrence Belzer October 2011 © 2011 Dan Terrence Belzer ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Susan Mason for her advisement and guidance throughout my graduate studies and thesis writing. Her insight and expertise have been invaluable to me. Additionally, I thank Dr. David Connors and Professor Jane McKeever for serving on my thesis committee and for giving me so much individual attention during my directed studies with them. I also thank my mother, Geraldine Belzer, who has been completely supportive of and interested in my endeavors and pursuits throughout my entire life. Her encouragement to pursue a graduate degree and her interest along the way, including discussing several of the plays I read in my coursework, made this journey all the more memorable. iii ABSTRACT THE SOUND AND MUSIC OF IBSEN By Dan Terrence Belzer Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen included specific sound and music stage directions and details in his nineteenth-century realistic prose plays. -

A Doll's House Henrik Ibsen

A Doll's House Henrik Ibsen ۳۲ Setting: The play takes place in Norway in the late ۱۹th century. The entire play is = set in one location, the city apartment of Torvald and Nora Helmer, a married couple. = The action of the play takes place over three days: Christmas Eve, Christmas Day and Boxing Day. = The main characters in the play are Nora and Torvald Helmer, Mrs Linde (Noraʼs childhood friend), Doctor Rank (a family friend) and Nils Krogstad (an employee at the bank of which Torvald has recently been made Director). Plot: The play opens on Christmas Eve. Nora returns home with a Christmas tree and presents for her three children. Her husband Torvald is at work in his study, but soon comes out into the living room to see what she’s bought. He chides Nora for being a squanderer and spending all their money; Nora responds by saying that surely they can let themselves go a little bit this year, now that he has been appointed Director of the bank and will be earning a good salary. They talk more about money; Nora says that all she wants for Christmas is money, so that she can buy herself something with it later; she also suggests that they borrow some money until Torvald receives his first pay packet, however Torvald rejects this suggestion as he doesn’t agree with borrowing money. The couple is very affectionate and playful together; Torvald calls Nora his songbird, his lark and his squirrel, and teases her about her sweet tooth. Noraʼs friend Mrs. -

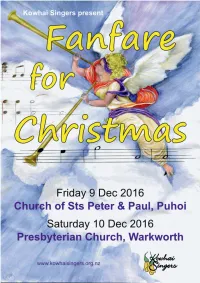

16-12 Prog.Pdf

Fanfare for Christmas The title of our concert is taken from our opening song for the full choir - Fanfare for Christmas Day: Gloria in Excelsis Deo, an anthem, by Martin Shaw. Martin Edward Fallas Shaw OBE FRCM (1875 – 1958) was an English composer, conductor and (in his early life) theatre producer. His over 300 published works include songs, hymns, carols, oratorios, several instrumental works, a congregational mass setting (the Anglican Folk Mass) and four operas including a ballad opera With a voice of Singing is another of his anthems in our repertoire, performed several times in the past at Kowhai Singers concerts. Conductor Peter Cammell (BA, Post Grad. Dip. Mus.) studied music at Auckland and Otago Universities and then taught in secondary schools in both Auckland and London. He has sung in the Dorian Choir, Auckland Anglican Cathedral Choir, Cantus Firmus, The Graduate Choir, Musica Sacra, Viva Voce, and is currently with Calico Jam. As director of the Kowhai Singers for 21 years Peter has worked hard to extend the choir's repertoire and singing skills and thereby their musical understanding. Accompanist Riette Ferreira (PhD) has been the choir's pianist for most of the time since August 2003 except when personal commitments such as study towards her PhD degree in Music has taken her away from us. She has wide experience teaching music in both South African and New Zealand schools and is frequently engaged as director and/or keyboard player for musical theatre productions at Centrestage Theatre, Orewa. Introit - Beata Viscera Marie Virginis† (words 12th C) Pontin Fanfare for Christmas Day: Gloria in Excelsis Deo Martin Shaw While shepherds watched their flocks (with the congregation) Welcome, Yule! (Anon. -

Production Staff

PRODUCTION STAFF S1:age Management MARY MANCHEGO,· assisted b-y jEFFREY EMBLER, ALBERT HEE Company Manager MARGARET BusH Lighting LAURA GARILAO and RoY McGALLIARD, assisted by DANIEL S. P. YANG, MIR MAGSUDUS SALAHEEN, CAROL ANZAI Costume Maintenance CARROLL RrcE, assisted by PEGGY PoYNTZ Costume Construction FRANCES ELLISON, assisted by DoRoTHY BLAKE, LouiSE HAMAl Scene Construction and Painting HELENE SHIRATORI, AMY YoNASHIRo, RrcHARD YoUNG, jEANNETTE ALLYN, FLoRENCE FUJITANI, RoNDA PHILLIPs, CYNTHIA BoYNToN, RosEMARIE ORDONEZ, JoAN YuHAs, IRENE KAME~A, WILLIAM SIEVERS, JoHN LANE, CHRISTOBEL KEALOHA, MILDRED YEE, CAROLYN LEE, ERNEST CocKETT, LoRRAINE SAITO, JumTH BAVERMAN, JosEPH PrscroTTE, DENNIS TANIGUCHI, jANICE YAMASAKI, VIRGINIA MENE FEE, LoursE ELSNER, CHARLES BouRNE, VERA STEVENSoN, GEORGE OKAMOTO Makeup MrR MAGsuous SALAHEEN, assisted by BARBARA BABBS Properties AMANDA PEcK, assisted b)• MARY MANCHEGO Sound ARTHUR PARSON Business Management JoAN LEE, assisted by ANN MIYAMOTO, jACKIE Mrucr, CAROL SoNENSHEIN, RANDY KrM, Juoy Or Public Relations JoAN LEE, assisted by SHEILA UEDA, DouG KAYA House Management FRED LEE GALLEGos, assisted by DAVE McCAULEY, HENRY HART, PAT ZANE, VERNON ToM, CLYDE WoNG, Eo GAYAGAS Ushers PHI DELTA SIGMA, WAKABA KAI, UNIVERSITY YWCA, EQUESTRIANS, HUI LoKAHI Actors' Representatives ANN MIYAMOTO, WILLIAM KROSKE Members of the classes in Dramatic Productio11 (Drama 150), Theatre Practice (Drama 200), and Advat~ced Theatre Practice (Drama 600) have assisted in the preparation of this production. THEATRE GROUP PRODUCTION CHAIRMEN Elissa Guardino Joan Lee Amanda Peck Fred Gallegos Ann Miyamoto Clifton Chun Arthur Parson Carol Sonenshein Lucie Bentley, Earle Erns,t, Edward Langhans, Donald Swinney, John Dreier, ~rthur Caldeira, Jeffrey Embler, Tom Kanak (Advisers-Directors) ACKNOWLEDGMENT The Theatre Group wishes to thank Star Furniture Co. -

Henrik Ibsen's Use Of

Henrik Ibsen’s use of ‘Friluftsliv’. by Dag T. Elgvin Presented at the conference: «Henrik Ibsen: The birth of ‘friluftsliv’ – a 150 years Celebration», North Trøndelag University College, Sept. 14th – 19th 2009 Summary This paper intends to explore Henrik Ibsen's concept of "Friluftsliv", as he incorporated it into his writing. Henrik Ibsen (1828-1906) is probably best known for his plays, which cast light over existential human issues. Freedom in life and obligations in marriage society, how one chooses right from wrong, and how one realizes his own talents and abilities, all are fundamental in his works. The concept "Friluftsliv" appears no more than two times in his writings, once in a play and once in a poem. 1 Both were written in a period when Ibsen was struggling to find his life's purpose. The poem "On The Heights" is considered to have a biographical strain (Hemmer, 2003). The poem's main character chooses a free life in the wilds of nature and away from the village in which he grew up. Ibsen chose to be a writer, to experience his freedom in this fashion, instead of following the wishes of his father, a pharmacist, who wanted his son to follow in his footsteps. In fact, Ibsen moved from Norway to Italy in 1864, when he was 36 years old, where he lived for 27 years. Henrik Ibsen's meaning with "Friluftsliv" might best be interpreted as the total appreciation of the experience one has when communing with the natural environment, not for sport or play, but for its value in the development of one's entire spiritual and physical being. -

Wexford Carol 1

q = 64 Wexford Carol 1. Good peo - ple all, this Christ-mas- time, con - si - der well and 2. The night be - fore that hap - py tide, the no - ble Vir - gin 3. Near Beth- le - hem did shep-herds keep theirflocks of lambs and 4. With thank-ful heart and joy - ful mind, the shep-herds went the 5. There were three wise men from a - far di - rec - ted by a bear in mind what our good God for us has done, in and her guide were long time seek - ing up and down to feed -ing sheep; to whom God's an - gels did ap - pear, which babe to find, and as God's an - gel had fore - told, they glo-rious star, and on they wan - dered night and day un- send-ing his be -lo - ved son. With Ma - ry ho - ly find a lodg - ing in the town. But mark how all things put the shep - herds in great fear. "Pre - pare and go," the did our Sav - ior Christ be - hold. With - in a man - ger til they came where Je - sus lay. And when they came un - WORDS: Traditional English and Irish (Mt. 1:18-2:11; Luke 2:1-20) WEXFORD CAROL MUSIC: Traditional Irish melody, arr. Martin Shaw (1875-1958) LMD Published by The General Board of Discipleship of The United Methodist Church, PO Box 340003, Nashville TN 37203. Website www.gbod.org/worship Source: The Oxford Book of Carols, compiled and edited by Percy Dearmer, R. Vaughan Williams, Martin Shaw. -

A Journey of Teaching Henrik Ibsen's a Doll House to Play Analysis

“ONLY CONNECT”: A JOURNEY OF TEACHING HENRIK IBSEN’S A DOLL HOUSE TO PLAY ANALYSIS STUDENTS Dena Michelle Davis, B.F.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2004 APPROVED: Andrew B. Harris, Major Professor Donald B. Grose, Committee Member and Dean of Libraries Timothy R. Wilson, Chair of the Department of Dance and Theatre Arts Sandra L. Terrell, Interim Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Davis, Dena Michelle, “Only Connect”: A Journey of Teaching Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll House to Play Analysis Students. Master of Arts (Theatre), May 2004, 89 pp., bibliography, 14 titles. This work examines the author’s experience in teaching A Doll House by Henrik Ibsen to students in the course Play Analysis, THEA 2440, at the University of North Texas in the Fall 2003 and Spring 2004 semesters. Descriptions of the preparations, presentations, student responses, and the author’s self-evaluations and observations are included. Included as appendices are a history of Henrik Ibsen to the beginning of his work on A Doll House, a description of Laura Kieler, the young woman on whose life Ibsen based the lead character, and an analysis outline form that the students completed for the play as a requirement for the class. Copyright 2004 by Dena Michelle Davis ii TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................1 PREPARATION: FALL 2003................................................................................3 PRESENTATION -

Ibsen - Chronology

Ibsen - Chronology http://ibsen.nb.no/id/1431.0 1828 Henrik Johan Ibsen born on March 20th in Stockmannsgården in Skien. Parents: Marichen (née Altenburg) and Knud Ibsen, merchant. 1835 Father has to give up his business. The properties are auctioned off. The family moves to Venstøp, a farm in Gjerpen. 1843 Confirmed in Gjerpen church. Family moves to Snipetorp in Skien. Ibsen leaves home in November. Arrives in Grimstad on November 29th to be apprenticed to Jens Aarup Reimann, chemist. 1846 Has an illegitimate child by Else Sophie Jensdatter, one of Reimann’s servants. 1847 Lars Nielsen takes over ownership of the chemist’s, moving to larger premises. 1849 Ibsen writes Catiline. 1850 Goes to Christiania to study for the university entrance examination. Catiline is published under the pseudonym Brynjolf Bjarme. Edits the Students’ Union paper Samfundsbladet and the satirical weekly Andhrimner. First Ibsen staging in history: the one-act The Burial Mound is performed at Christiania Theatre on September 26th. 1851 Moves to Bergen to begin directing productions at Det norske Theatre. Study tour to Copenhagen and Dresden. 1853 First performance of St. John’s Night. 1854 First performance of The Burial Mound in a revised version. 1855 First performance of Lady Inger. 1856 First performance of The Feast at Solhaug. Becomes engaged to Suzannah Thoresen. 1857 First performance of Olaf Liljekrans. Is appointed artistic director of Kristiania Norske Theatre. 1858 Marries Suzannah Thoresen on June 18th. First performance of The Vikings at Helgeland. 1859 Writes the poem "Paa Vidderne" ("Life on the Upland") and the cycle of poems "I billedgalleriet" ("At the Art Gallery"). -

Holst and Vaughan Williams Manuscripts at Liverpool Cathedral

HOLST AND VAUGHAN WILLIAMS MANUSCRIPTS AT LIVERPOOL CATHEDRAL Judith The recent discovery of a small collection of manuscripts at the Anglican Cathedral, Liverpool, has shed light on a precisely identifiable but now almost forgotten period in the late 1920s and early 1930s when the Cathedral provided the initial context for various innovations in church music, some of which have become established as enduring features of the repertory. The collection also gives an insight into the working methods of two composers whose importance extends far beyond that of their contributions to English church music: Gustav Hoist and Ralph Vaughan Williams. The collection consists chiefly of correspondence, dating from c. 1930 to 1951, between the Dean of the Cathedral and various distinguished individuals including Hoist, Vaughan Williams and the composer Martin Shaw (1875 1958). Of particular interest are two manuscripts of music: an autograph draft score of Hoist's anthem Eternal Father, who didst all create] and a printed vocal score annotated by the composer, with corresponding autograph manuscript instrumental parts, of the Te Deum in G by Vaughan Williams. The Cathedral archive is essentially a private one without facilities for research, and the discovery of these manuscripts was fortuitous. As an aid to scholars, therefore, the Cathedral authorities kindly permitted the manuscripts to be photographed. One complete set of photographs is now held by the Department of Music at Liverpool Univer sity. Of the second set of photographs, those showing the hand of Gustav Hoist are now in the possession of the Hoist 162 J. Foundation. Those pertaining to Ralph Vaughan Williams have been donated to the Department of Manuscripts at the British Library by Mrs Ursula Vaughan Williams. -

Henrik Ibsen and Isadora Duncan” Author: India Russell Source: Temenos Academy Review 17 (2014) Pp

THE TEMENOS ACADEMY “Expressing the Inexpressible: Henrik Ibsen and Isadora Duncan” Author: India Russell Source: Temenos Academy Review 17 (2014) pp. 148-177 Published by The Temenos Academy Copyright © The Estate of India Russell, 2014 The Temenos Academy is a Registered Charity in the United Kingdom www.temenosacademy.org 148-177 Russell Ibsen Duncan.qxp_Layout 1 04/10/2014 13:32 Page 148 Expressing the Inexpressible: Henrik Ibsen and Isadora Duncan * India Russell he two seemingly opposing forces of Isadora Duncan and Henrik TIbsen were complementary both in their spirit and in their epic effect upon the world of dance and drama, and indeed upon society in general. From the North and from the West, Ibsen and Isadora flashed into being like two unknown comets hurtling across the heavens, creat - ing chaos and upheaval as they lit up the dark spaces of the world and, passing beyond our ken, leaving behind a glimmering trail of profound change, as well as misunderstanding and misinterpretation. I would like to show how these two apparently alien forces were driven by the same rhythmical and spiritual dynamics, ‘towards the Joy and the Light that are our final goal’. That a girl of nineteen, with no credentials, no institutional backing and no money should challenge the artistic establishment of wealthy 1890s San Francisco with the declaration of her belief in Truth and Beauty, telling a theatre director that she had discovered the danc e— ‘the art which has been lost for two thousand years’; and that, twenty years earlier, a young man, far away from the centres of culture in hide-bound nineteenth -century Norway, should challenge the beliefs and double standards of contemporary society, showing with his revolutionary plays a way out of the mire of lies and deception up into the light of Truth, is as astounding as the dramatic realisation of their ideals. -

Unfaithfulness of Elida Wangel Reflected at Henrik Ibsen’S the Lady from the Sea (1888): a Psychoanalytic Approach

UNFAITHFULNESS OF ELIDA WANGEL REFLECTED AT HENRIK IBSEN’S THE LADY FROM THE SEA (1888): A PSYCHOANALYTIC APPROACH PUBLICATION ARTICLE Submitted as a Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Getting Bachelor Degree of Education in English Department by ERLANGGA DJATI A320110044 SCHOOL OF TEACHER TRAINING AND EDUCATION MUHAMMADIYAH UNIVERSITY OF SURAKARTA 2016 APROVAL AUTHENTICITY UNFAITHFULNESS OF ELIDA WANGEL REFLECTED AT HENRIK IBSEN’S THE LADY FROM SEA (1888): A PSYCHOANALYTIC APPROACH Erlangga Djati Dr. Phil. Dewi Chandraningrum, M. Ed Siti Fatimah, S.Pd., M.Hum. Department of English Education, Muhammadiyah University of Surakarta Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT ERLANGGA DJATI. A320110044. UNFAITHFULNESS OF ELIDA WANGEL REFLECTED AT HENRIK IBSEN’S THE LADY FSEA (1888): A PSYCHOANALYTIC APPROACH. Research Paper. School of Teacher Training and Education, Muhammadiyah University of Surakarta. February, 2016. The problem of this study is ―How is the the personality of Ellida Wangel reflected in Henrik Ibsen’s Lady from the sea play?‖. The objective of this study to analyze Lady from the sea based on Structural analysis and the to analyze Lady from the sea play based on Psychoanalytic perspective. The researcher employs qualitative method. The writer uses two data sources: primary and secondary. The primary data source is about The primary data sources is the textplay itself. Then, the secondary data sources are from other sources such as essay, articles, biography of Henrik Ibsen, Internet and other relevant information. The method of data collection is library research and the technique of data collection is descriptive technique. Based on the anaylisis, the researcher get some conclusions. -

IBSEN News and Comment the Journal of the Ibsen Society of America Vol

IBSEN News and Comment The Journal of The Ibsen Society of America Vol. 28 (2008) Phoenix Theatre, New York, An Enemy of the People, page 12 Gerry Goodstein IBSEN ON STAGE, 2008 From the Midwest: Two Minnesota Peer Gynt’s: Jim Briggs 2 From Dublin: The Gate’s Hedda Gabler: Irina Ruppo Malone 6 From New York: the Irish Rep’s Master Builder and the Phoenix’s Enemy: Marvin Carlson 10 From Stockholm: the Stadsteater’s Wild Duck: Mark Sandberg 14 NEWS AND NOTICES Ibseniana: The Rats’ Peer Gynt 16 ISA at SASS, 2009; Amazon’s Ibsen Collection, the Commonweal Ibsen Festival 17 IBSEN IN PRINT Annual Survey of Articles 18 Book Review: Thomas Van Laan on Helge Rønning’s Den Umulige Friheten. Henrik Ibsen og 43 Moderniteten (The Impossible Freedom. Henrik Ibsen and Modernity) The Ibsen Society of America Department of English, Long Island University, Brooklyn, New York 11201 www.ibsensociety.liu.edu Established in 1978 Rolf Fjelde, Founder is a production of The Ibsen Society of America and is sponsored by support from Long Island University, Brooklyn. Distributed free of charge to members of the So- ciety. Information on membership in the Society and on library rates for Ibsen News and Comment is available on the Ibsen Society web site: www.ibsensociety.liu.edu ©2008 by the Ibsen Society of America. ISSN-6171. All rights reserved. Editor, Joan Templeton Editor’s Note: We try to cover important U.S. productions of Ibsen’s plays as well as significant foreign pro- ductions. Members are encouraged to volunteer; please contact me at [email protected] if you are interested in reviewing a particular production.