Nepali Hindu Women's Thorny Path to Liberation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

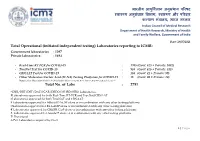

Laboratories Reporting to ICMR

भारतीय आयु셍वज्ञि ान अनुसंधान पररषद वा्य अनुसंधान 셍वभाग, वा्य और पररवार क쥍याण मंत्रालय, भारत सरकार Indian Council of Medical Research Department of Health Research, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India Date: 28/07/2021 Total Operational (initiated independent testing) Laboratories reporting to ICMR: Government laboratories : 1297 Private laboratories : 1494 - Real-Time RT PCR for COVID-19 : 1705 (Govt: 623 + Private: 1082) - TrueNat Test for COVID-19 : 938 (Govt: 625 + Private: 313) - CBNAAT Test for COVID-19 : 130 (Govt: 41 + Private: 89) - Other Molecular-Nucleic Acid (M-NA) Testing Platforms for COVID-19 : 18 (Govt: 08 + Private: 10) Note: Other Molecular-Nucleic Acid includes Abbott ID NOW, RT-LAMP, CRISPR-Cas9 and Accula™ Total No. of Labs : 2791 *CSIR/DBT/DST/DAE/ICAR/DRDO/MHRD/ISRO Laboratories. #Laboratories approved for both Real-Time RT-PCR and TrueNat/CBNAAT $Laboratories approved for both TrueNAT and CBNAAT ¥ Laboratories approved for Abbott ID NOW alone or in combination with any other testing platforms @Laboratories approved for RT-LAMP alone or in combination with any other testing platforms € Laboratories approved for CRISPR-Cas9 alone or in combination with any other testing platforms δ Laboratories approved for Accula™ alone or in combination with any other testing platforms P: Provisional Δ Pvt. Laboratories acquired by Govt. 1 | P a g e S. Test Names of States Names of Government Institutes Names of Private Institutes No. Category 1. Andhra Pradesh RT-PCR 1. Sri Venkateswara Institute of Medical 1. Manipal Hospital, Tadepalli, Guntur (131) Sciences, Tirupati 2. -

Nepal Side, We Must Mention Prof

The Journal of Newar Studies Swayambhv, Ifliihichaitya Number - 2 NS 1119 (TheJournal Of Newar Studies) NUmkL2 U19fi99&99 It has ken a great pleasure bringing out the second issue of EdltLlo the journal d Newar Studies lijiiiina'. We would like to thank Daya R Sha a Gauriehankar Marw&~r Ph.D all the members an bers for their encouraging comments and financial support. ivc csp~iilly:-l*-. urank Prof. Uma Shrestha, Western Prof.- Todd ttwria Oregon Univers~ty,who gave life to this journd while it was still in its embryonic stage. From the Nepal side, we must mention Prof. Tej Shta Sudip Sbakya Ratna Kanskar, Mr. Ram Shakya and Mr. Labha Ram Tuladhar who helped us in so many ways. Due to our wish to publish the first issue of the journal on the Sd Fl~ternatioaalNepal Rh&a levi occasion of New Nepal Samht Year day {Mhapujii), we mhed at the (INBSS) Pdand. Orcgon USA last minute and spent less time in careful editing. Our computer Nepfh %P Puch3h Amaica Orcgon Branch software caused us muble in converting the files fm various subrmttd formats into a unified format. We learn while we work. Constructive are welcome we try Daya R Shakya comments and will to incorporate - suggestions as much as we can. Atedew We have received an enormous st mount of comments, Uma Shrcdha P$.D.Gaurisbankar Manandhar PIID .-m -C-.. Lhwakar Mabajan, Jagadish B Mathema suggestions, appreciations and so forth, (pia IcleI to page 94) Puma Babndur Ranjht including some ~riousconcern abut whether or not this journal Rt&ld Rqmmtatieca should include languages other than English. -

Convened by the Peace Council and the Center for Health and Social

CHSP_Report_cover.qxd Printer: Please adjust spine width if necessary. Additional copies of this report may be obtained from: ............................................................................................................. ............................................................................................................. International Committee for the Peace Council The Center for Health and Social Policy 2702 International Lane, Suite 108 847 25th Avenue Convened by The Peace Council and The Center for Health and Social Policy Madison, WI 53704 San Francisco, CA 94121 United States United States Chiang Mai, Thailand 1-608-241-2200 Phone 1-415-386-3260 Phone February 29–March 3, 2004 1-608-241-2209 Fax 1-415-386-1535 Fax [email protected] [email protected] www.peacecouncil.org www.chsp.org ............................................................................................................. Copyright © 2004 by The Center for Health and Social Policy and The Peace Council ............................................................................................................. Convened by The Peace Council and The Center for Health and Social Policy Chiang Mai, Thailand February 29–March 3, 2004 Contents Introduction 5 Stephen L. Isaacs and Daniel Gómez-Ibáñez The Chiang Mai Declaration: 9 Religion and Women: An Agenda for Change List of Participants 13 Background Documents World Religions on Women: Their Roles in the Family, 19 Society, and Religion Christine E. Gudorf Women and Religion in the Context of Globalization 49 Vandana Shiva World Religions and the 1994 United Nations 73 International Conference on Population and Development A Report on an International and Interfaith Consultation, Genval, Belgium, May 4-7, 1994 3 Introduction Stephen L. Isaacs and Daniel Gómez-Ibáñez Forty-eight religious and women’s leaders participated in a “conversation” in Chi- ang Mai, Thailand between February 29 and March 3, 2004 to discuss how, in an era of globalization, religions could play a more active role in advancing women’s lives. -

South-Indian Images of Gods and Goddesses

ASIA II MB- • ! 00/ CORNELL UNIVERSITY* LIBRARY Date Due >Sf{JviVre > -&h—2 RftPP )9 -Af v^r- tjy J A j£ **'lr *7 i !! in ^_ fc-£r Pg&diJBii'* Cornell University Library NB 1001.K92 South-indian images of gods and goddesse 3 1924 022 943 447 AGENTS FOR THE SALE OF MADRAS GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. IN INDIA. A. G. Barraud & Co. (Late A. J. Combridge & Co.)> Madras. R. Cambrav & Co., Calcutta. E. M. Gopalakrishna Kone, Pudumantapam, Madura. Higginbothams (Ltd.), Mount Road, Madras. V. Kalyanarama Iyer & Co., Esplanade, Madras. G. C. Loganatham Brothers, Madras. S. Murthv & Co., Madras. G. A. Natesan & Co., Madras. The Superintendent, Nazair Kanun Hind Press, Allahabad. P. R. Rama Iyer & Co., Madras. D. B. Taraporevala Sons & Co., Bombay. Thacker & Co. (Ltd.), Bombay. Thacker, Spink & Co., Calcutta. S. Vas & Co., Madras. S.P.C.K. Press, Madras. IN THE UNITED KINGDOM. B. H. Blackwell, 50 and 51, Broad Street, Oxford. Constable & Co., 10, Orange Street, Leicester Square, London, W.C. Deighton, Bell & Co. (Ltd.), Cambridge. \ T. Fisher Unwin (Ltd.), j, Adelphi Terrace, London, W.C. Grindlay & Co., 54, Parliament Street, London, S.W. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. (Ltd.), 68—74, iCarter Lane, London, E.C. and 25, Museum Street, London, W.C. Henry S. King & Co., 65, Cornhill, London, E.C. X P. S. King & Son, 2 and 4, Great Smith Street, Westminster, London, S.W.- Luzac & Co., 46, Great Russell Street, London, W.C. B. Quaritch, 11, Grafton Street, New Bond Street, London, W. W. Thacker & Co.^f*Cre<d Lane, London, E.O? *' Oliver and Boyd, Tweeddale Court, Edinburgh. -

DELHI DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY (LIST of Pios & Faas As on 22.06

DELHI DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY (LIST of PIOs & FAAs as on 22.06.2020) Central Public Information Officers & Appellate Authorities Following are the details of Central Public Information Officers and Appellate Authority in different departments of DDA Sl. Designation & Telephone Jurisdiction Designation & Telephone A.O. for Offices from No. Address of (Office)/E-Mail Address of First (Office)/E-Mail Collection of where the CPIOs ID Appellate Authority ID Fees Application can be obtainned/ submitted 1. LAND DISPOSAL A.O. DEPTT. (Cash)Main C- Sh. Rajpal, Ph. Sh. P.S. Joshi, Block, Ground Window No. 15, Asstt. Director 24690431/35 1.Rohini Dy. Direct Ph. Floor, Vikas Near Main (GH), Room No. 2.Dwarka or (GH), Room No. 24690431/35 Sadan, DDA, Reception in ‘D’ 202, C-III 2nd Extn. 1642. 215, C-III 2nd Floor, INA, Delhi-23 Block, Vikas Floor, Vikas Vikas Sadan, INA, Extn.1625 Sadan, INA, Sadan, INA, New New Delhi-110023. Delhi-110023. Delhi-110023. 2. Asstt. Director 1.Vikas Puri Sh. P.S. Joshi Ph. A.O. (Cash) Window No. 15, (GH), Room No. Ph. 2.Pitam Pura Dy. Director (GH), 24690431/35 Main C-Block, Near Main 203, C-III 2nd 24690431/35 3.Pashchim Vihar Room No. 215, C-III Ground Floor, Reception in ‘D’ Floor, Vikas 4. Rohtak Road 2nd floor, Vikas Extn.1625 Vikas Sadan, Block, Vikas Sadan, INA, New Extn. 1641. 5. Mayur Vihar Sadan, INA, New DDA, INA, Sadan, INA, New Delhi-110023. 6. Patpar Ganj Delhi-110023. New Delhi- Delhi-110023. 7. I.P. Extn. 110023. 8. Vasundhra 9. -

Recasting Caste: Histories of Dalit Transnationalism and the Internationalization of Caste Discrimination

Recasting Caste: Histories of Dalit Transnationalism and the Internationalization of Caste Discrimination by Purvi Mehta A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology and History) in the University of Michigan 2013 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Farina Mir, Chair Professor Pamela Ballinger Emeritus Professor David W. Cohen Associate Professor Matthew Hull Professor Mrinalini Sinha Dedication For my sister, Prapti Mehta ii Acknowledgements I thank the dalit activists that generously shared their work with me. These activists – including those at the National Campaign for Dalit Human Rights, Navsarjan Trust, and the National Federation of Dalit Women – gave time and energy to support me and my research in India. Thank you. The research for this dissertation was conducting with funding from Rackham Graduate School, the Eisenberg Center for Historical Studies, the Institute for Research on Women and Gender, the Center for Comparative and International Studies, and the Nonprofit and Public Management Center. I thank these institutions for their support. I thank my dissertation committee at the University of Michigan for their years of guidance. My adviser, Farina Mir, supported every step of the process leading up to and including this dissertation. I thank her for her years of dedication and mentorship. Pamela Ballinger, David Cohen, Fernando Coronil, Matthew Hull, and Mrinalini Sinha posed challenging questions, offered analytical and conceptual clarity, and encouraged me to find my voice. I thank them for their intellectual generosity and commitment to me and my project. Diana Denney, Kathleen King, and Lorna Altstetter helped me navigate through graduate training. -

Dissertation Abstracts

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 6 Number 3 Himalayan Research Bulletin 1986 Article 6 Fall 1986 Dissertation Abstracts Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation . 1986. Dissertation Abstracts. HIMALAYA 6(3). Available at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol6/iss3/6 This Dissertation Abstract is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Courtesy of Fronk Joseph Shulman, Compiler and Editor Doctoral Dissertation on Asia: An Annotated Bibliographical Journal of Current International Research (c/o East Asia Collection, McKelddin Libmry University of Maryland, College Park, MD. 20742 U.S.A.) University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Ann Arbor, MI 48106 U.S.A. (W ATS telephone number: 1-800-521-06(0) NOTE: We are aware that some universities do not submit dissertations or abstracts to the central dissertation services. If your dissertation is not generally available, or if you know of one that is not, please send us the necessary information so that our listings can be more complete. The SwastMni Vrata: Newar Women and Ritual in Nepal. Order No. DA8528426 Swasthani, the Goddess of Own Place, is popularly worshipped by women and families in Nepal. Worship of SwastMni centers on a month-long ritual recitation of the Swasthclni Vrata Kathd, a book of stories concerning her various emanations, the oldest manuscripts of which appear in Nepalbhasa, or Newari. -

The Menstrual Taboo and Modern Indian Identity

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Honors College at WKU Projects 6-28-2017 The eM nstrual Taboo and Modern Indian Identity Jessie Norris Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses Part of the Hindu Studies Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Norris, Jessie, "The eM nstrual Taboo and Modern Indian Identity" (2017). Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Projects. Paper 694. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses/694 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Capstone Experience/ Thesis Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE MENSTRUAL TABOO AND MODERN INDIAN IDENTITY A Capstone Project Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of History and Degree Bachelor of Anthropology With Honors College Distinction at Western Kentucky University By Jessie Norris May 2017 **** CE/T Committee: Dr. Tamara Van Dyken Dr. Richard Weigel Sharon Leone 1 Copyright by Jessie Norris May 2017 2 I dedicate this thesis to my parents, Scott and Tami Norris, who have been unwavering in their support and faith in me throughout my education. Without them, this thesis would not have been possible. 3 Acknowledgements Dr. Tamara Van Dyken, Associate Professor of History at WKU, aided and counseled me during the completion of this project by acting as my Honors Capstone Advisor and a member of my CE/T committee. -

The Teaching of Buddha”

THE TEACHING OF BUDDHA WHEEL OF DHARMA The Wheel of Dharma is the translation of the Sanskrit word, “Dharmacakra.” Similar to the wheel of a cart that keeps revolving, it symbolizes the Buddha’s teaching as it continues to be spread widely and endlessly. The eight spokes of the wheel represent the Noble Eightfold Path of Buddhism, the most important Way of Practice. The Noble Eightfold Path refers to right view, right thought, right speech, right behavior, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right meditation. In the olden days before statues and other images of the Buddha were made, this Wheel of Dharma served as the object of worship. At the present time, the Wheel is used internationally as the common symbol of Buddhism. Copyright © 1962, 1972, 2005 by BUKKYO DENDO KYOKAI Any part of this book may be quoted without permission. We only ask that Bukkyo Dendo Kyokai, Tokyo, be credited and that a copy of the publication sent to us. Thank you. BUKKYO DENDO KYOKAI (Society for the Promotion of Buddhism) 3-14, Shiba 4-chome, Minato-ku, Tokyo, Japan, 108-0014 Phone: (03) 3455-5851 Fax: (03) 3798-2758 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.bdk.or.jp Four hundred & seventy-second Printing, 2019 Free Distribution. NOT for sale Printed Only for India and Nepal. Printed by Kosaido Co., Ltd. Tokyo, Japan Buddha’s Wisdom is broad as the ocean and His Spirit is full of great Compassion. Buddha has no form but manifests Himself in Exquisiteness and leads us with His whole heart of Compassion. -

Environmental Compliance Monitoring Report

Environmental Compliance Monitoring Report Semi-Annual Report January 2021 Project Number: 51190-001 Nepal: Disaster Resilience of Schools Project Prepared by the Central Level Project Implementation Unit (Education) of National Reconstruction Authority for the Asian Development Bank. This Environmental Compliance Monitoring Report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Semi-annual Environmental Compliance Monitoring Report July-December 2020 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank BoQ - Bill of Quantities CLPIU - Central Level Project Implementation Unit COVID-19 2019 novel coronavirus DRSP - Disaster Resilience Schools Project DSC – Design and Supervision Consultant DUDBC – Department of Urban Development and Building Construction DLPIU - District Level Project Implementation Unit EA – Executing Agency EARF - Environmental Assessment and Review Framework EEAP - Earthquake Emergency Assistance Project EMP - Environmental Management Plan EPR - Environment Protection Rules GON – Government of Nepal GRC – Grievance Redress Committee IA – Implementing Agency IEE - Initial Environmental Examination LOC - Land Ownership Certificate MoSTE - Ministry of Education, Science and Technology NRA - National Reconstruction Authority PAM – Project Administration Manual PD – Project Director PIU – Project Implementation Unit PPE - Personal Protective Equipment RE - Residence Engineer REA - Rapid Environment Assessment Recon - Re-construction SE - Site Engineer Sq. -

Bus Routes & Timings

BUS ROUTES & TIMINGS ACADEMIC YEAR 2015 - 2016 ROUTE NO. 15 ROUTE NO. 1 to 12, 50, 54, 55, 56, 61,64,88, RAJA KILPAKKAM TO COLLEGE 113,117 to 142 R2 - RAJ KILPAKKAM : 07.35 a.m. TAMBARAM TO COLLEGE M11 - MAHALAKSHMI NAGAR : 07.38 a.m. T3 - TAMBARAM : 08.20 a.m. C2 - CAMP ROAD : 07.42 a.m. COLLEGE : 08.40 a.m. S11 - SELAIYUR : 07.44 a.m. A4 - ADHI NAGAR : 07.47 a.m. ROUTE NO. 13 C19 - CONVENT SCHOOL : 07.49 a.m. KRISHNA NAGAR - ITO COLLEGE COLLEGE : 08.40 a.m. K37 - KRISHNA NAGAR (MUDICHUR) : 08.00 a.m. R4 - RAJAAMBAL K.M. : 08.02 a.m. ROUTE NO. 16 NGO COLONY TO COLLEGE L2 - LAKSHMIPURAM SERVICE ROAD : 08.08 a.m. N1 - NGO COLONY : 07.45 a.m. COLLEGE : 08.40 a.m. K6 - KAKKAN BRIDGE : 07.48 a.m. A3 - ADAMBAKKAM : 07.50 a.m. (POLICE STATION) B12 – ROUTE NO. 14 BIKES : 07.55 a.m. KONE KRISHNA TO COLLEGE T2 - T. G. NAGAR SUBWAY : 07. 58 a.m. K28 - KONE KRISHNA : 08.05 a.m. T3 - TAMBARAM : 08.20 a.m. L5 - LOVELY CORNER : 08.07 a.m. COLLEGE : 08.40 a.m. ROUTE NO. 17 ADAMBAKKAM - II TO COLLEGE G3 - GANESH TEMPLE : 07.35 a.m. V13 - VANUVAMPET CHURCH : 07.40 a.m. J3 - JAYALAKSHMI THEATER : 07.43 a.m. T2 - T. G. NAGAR SUBWAY : 07.45 a.m. T3 - TAMBARAM : 08.20 a.m. COLLEGE : 08.40 a.m. ROUTE NO. 18 KANTHANCHAVADI TO COLLEGE ROUTE NO.19 NANGANALLUR TO COLLEGE T 43 – THARAMANI Rly. -

Interpreting the Human Rights Field

Journal of Human Rights Practice, 2021, 1–21 Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jhrp/advance-article/doi/10.1093/jhuman/huab005/6275395 by University of British Columbia user on 18 May 2021 doi: 10.1093/jhuman/huab005 Dialogue Dialogue Interpreting the Human Rights Field: A Conversation Laura Kunreuther, Shiva Acharya, Ann Hunkins, Sachchi Ghimire Karki, Hikmat Khadka, Loknath Sangroula, Mark Turin, Laurie Vasily* Abstract This article takes the form of a conversation between an anthropologist and seven interpreters who worked for the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) during its mission in Nepal (2005–2011). As any human rights or humanitarian worker knows quite well, an interpreter is essential to any field mission; they are typically the means by which ‘internationals’ are able to speak to any local person. Interpreters make it possible for local events to be transformed into a globally legible register of human rights abuses or cases. Field interpreters are therefore crucial to realizing the global ambitions of any bureaucracy like the UN. Yet rarely do human rights officers or academics (outside of translation studies) hear from interpreters themselves about their experience in the field. This conversa- tion is an attempt to bridge this lacuna directly, in the hope that human rights practitioners and academics might benefit from thinking more deeply about the people upon whom our knowledge often depends. Keywords: field interpreters; Nepal; Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights; UN human rights