Norse and Celtic Place-Names Around the Dornoch Firth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Divided We Stand POLITEIA

Peter Fraser Divided We Stand Scotland a Nation Once Again? POLITEIA A FORUM FOR SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC THINKING POLITEIA A Forum for Social and Economic Thinking Politeia commissions and publishes discussions by specialists about social and economic ideas and policies. It aims to encourage public discussion on the relationship between the state and the people. Its aim is not to influence people to support any given political party, candidates for election, or position in a referendum, but to inform public discussion of policy. The forum is independently funded, and the publications do not express a corporate opinion, but the views of their individual authors. www.politeia.co.uk Divided We Stand Scotland a Nation Once Again? Peter Fraser POLITEIA 2012 First published in 2012 by Politeia 33 Catherine Place London SW1E 6DY Tel. 0207 799 5034 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.politeia.co.uk © Politeia 2012 Essay Series ISBN 978-0-9571872-0-7 Cover design by John Marenbon Printed in Great Britain by: Plan – IT Reprographics Atlas House Cambridge Place Hills Road Cambridge CB2 1NS THE AUTHOR Lord Fraser of Carmyllie QC Lord Fraser of Carmyllie QC was the Conservative Member of Parliament for Angus South (1979-83) and Angus East (1983-87) and served as Solicitor General for Scotland from 1982-88. He became a peer in 1989 and served as Lord Advocate (1989-92), Minister of State at the Scottish Office (1992-95) and the Department of Trade and Industry (1995-97). He was Deputy Leader of the Opposition from 1997-98. His publications include The Holyrood Inquiry, a 2004 report on the Holyrood building project. -

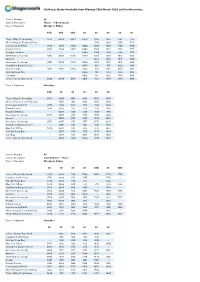

BCS Paper 2016/13

Boundary Commission for Scotland BCS Paper 2016/13 2018 Review of Westminster Constituencies Considerations for constituency design in Highland and north of Scotland Action required 1. The Commission is invited to consider the issue of constituency size when designing constituencies for Highland and the north of Scotland and whether it wishes to propose a constituency for its public consultation outwith the electorate quota. Background 2. The legislation governing the review states that no constituency is permitted to be larger than 13,000 square kilometres. 3. The legislation also states that any constituency larger than 12,000 square kilometres may have an electorate lower than 95% of the electoral quota (ie less than 71,031), if it is not reasonably possible for it to comply with that requirement. 4. The constituency size rule is probably only relevant in Highland. 5. The Secretariat has considered some alternative constituency designs for Highland and the north of Scotland for discussion. 6. There are currently 3 UK Parliament constituencies wholly with Highland Council area: Caithness, Sutherland and Easter Ross – 45,898 electors Inverness, Nairn, Badenoch and Strathspey – 74,354 electors Ross, Skye and Lochaber – 51,817 electors 7. During the 6th Review of UK Parliament constituencies the Commission developed proposals based on constituencies within the electoral quota and area limit. Option 1 – considers electorate lower than 95% of the electoral quota in Highland 8. Option 1: follows the Scottish Parliament constituency of Caithness, Sutherland and Ross, that includes Highland wards 1 – 5, 7, 8 and part of ward 6. The electorate and area for the proposed Caithness, Sutherland and Ross constituency is 53,264 electors and 12,792 sq km; creates an Inverness constituency that includes Highland wards 9 -11, 13-18, 20 and ward 6 (part) with an electorate of 85,276. -

Easy Guide Highland

EEaassyy GGuuiiddee HHiigghhllaanndd IInntteeggrraatteedd CChhiillddrreenn’’ss SSeerrvviicceess 2 “Getting it right for every child - Highland’s Children” The Children’s Services Managers Group (SMG) is the lead body of Managers involved in the provision of services for children & young people. The SMG is tasked with ensuring strong integration and high quality of services for children and families in Highland. Encompassing Education, Social Work, NHS, Northern Constabulary and partner services and agencies, the SMG facilitates the development of services and professional networks around Associated School Groups and their communities. As part of our commitment to ensuring best use of resources and early intervention this guide has been developed to assist you. This Easy Guide has been updated at the request of local staff who found the previous edition a useful element of their resources library. We are keen to ensure staff know what resources are available. This information is ever changing. Consequently, the Easy Guide focuses on directing you to resource web sites, ensuring you see the most up to date information on a service or resource. When working with a child & family a Named Person or Lead Professional will find this updated Easy Guide a useful tool for tracking down resources to help in the development of a Childs Plan. Equally, it is hoped that it will be of use to all staff working with children and young people. The Easy Guide will be updated on a regular basis. If you become aware of any amendments, errors or additions please forward to Maggie Tytler. Please do not hesitate to let us know of ways in which this resource might be improved. -

Simplicity at Our Core

SIMPLICITY AT OUR CORE PORTFOLIO Contents OUR BUILDINGS Findhorn•Sands, p3 Bonlokke, p10 Social Bite Homeless Village, p17 Bonsall, p4 Mackinnon, p11 Nedd House, p18 Dionard, p5 Salvesen, p12 Dyson IET, p19 Hill•Cottage, p6 Woodlands Workspace (Artists Hub), p13 Virtual Reality, p20 Alness, p7 Helmsdale•Recording Studio, p14 Team, p21 Kingsmills, p8 Findhorn•Eco•Wedge, p15 Fit•Homes, p16 Unit 17 Cromarty Firth Industrial Park, Bunchrew, p9 Invergordon, UK, IV18 0LT About Us Carbon Dynamic is a world leader in modular timber manufacture. “Our goal is to provide everything you will ever need to achieve your build under the one roof. We strive to free ourselves from the complexity At Carbon Dynamic we design and manufacture beautiful timber and intricacy of the traditional build process believing the simpler the modular buildings with exceptional levels of insulation, airtightness and process the less stressful and more enjoyable it becomes”. sustainability. We’re dedicated to providing cost effective, low energy Matt Stevenson, Director buildings using locally-sourced and sustainable materials. Findhorn Eco Lodges Part of the long-term development adjacent to the sand dunes of Findhorn, each of these lodges are individually owned and designed. Laid to a Findhorn, Scotland curve, each lodge has its own unique views and high levels of privacy. Although externally similar the design of these lodges is so flexible that 1,2 or Residential, 2015 3 bedroom or even completely open-planned layouts are possible. Unit 17 Cromarty Firth Industrial Park, Invergordon, UK, IV18 0LT 3 Bonsall Eco Lodge Contemporary, open plan living with oak floors. Painted in calming tones and everything a guest should require for a comfortable and enjoyable Brodie, Scotland stay, with the capacity to accommodate four guests. -

Rosehall Information

USEFUL TELEPHONE NUMBERS Rosehall Information POLICE Emergency = 999 Non-emergency NHS 24 = 111 No 21 January 2021 DOCTORS Dr Aline Marshall and Dr Scott Smith PLEASE BE AWARE THAT, DUE TO COVID-RELATED RESTRICTIONS Health Centre, Lairg: tel 01549 402 007 ALL TIMES LISTED SHOULD BE CHECKED Drs C & J Mair and Dr S Carbarns This Information Sheet is produced for the benefit of all residents of Creich Surgery, Bonar Bridge: tel 01863 766 379 Rosehall and to welcome newcomers into our community DENTISTS K Baxendale / Geddes: 01848 621613 / 633019 Kirsty Ramsey, Dornoch: 01862 810267; Dental Laboratory, Dornoch: 01862 810667 We have a Village email distribution so that everyone knows what is happening – Golspie Dental Practice: 01408 633 019; Sutherland Dental Service, Lairg: 402 543 if you would like to be included please email: Julie Stevens at [email protected] tel: 07927 670 773 or Main Street, Lairg: PHARMACIES 402 374 (freephone: 0500 970 132) Carol Gilmour at [email protected] tel: 01549 441 374 Dornoch Road, Bonar Bridge: 01863 760 011 Everything goes out under “blind” copy for privacy HOSPITALS / Raigmore, Inverness: 01463 704 000; visit 2.30-4.30; 6.30-8.30pm There is a local residents’ telephone directory which is available from NURSING HOMES Lawson Memorial, Golspie: 01408 633 157 & RESIDENTIAL Wick (Caithness General): 01955 605 050 the Bradbury Centre or the Post Office in Bonar Bridge. Cambusavie Wing, Golspie: 01408 633 182; Migdale, Bonar Bridge: 01863 766 211 All local events and information can be found in the -

Caithness Guide Timetable from Monday 23Rd March 2020 Until Further Notice

Caithness Guide timetable from Monday 23rd March 2020 until further notice. Service Number 80 Service Description Thurso - John O Groats Days of Operation Monday to Friday 80D 80D 80D 80 80 80 80 80 Thurso Olrig St Santander 0551 0608 0640 0830 1025 1235 1545 1735 Mount Pleasant Towerhill Road - - - - 1030 1240 1550 1740 Castletown Drill Hall 0601 0618 0650 0840 1039 1249 1559 1749 Dunnet Corner 0607 0624 0656 0846 1045 1255 1605 1755 Brough Letterbox - - - 0849 1048 1258 1608 1758 Greenvale Crossroads 0611 0628 0700 0854 1053 1303 1613 1803 Barrock - - - - 1055 1305 1616 1806 Greenvale Crossroads 0611 0628 0700 0854 1057 1307 1618 1808 Scarfskerry Baptist Church - - - 0858 1101 1311 1622 1812 Mey Post Office 0615 0632 0704 904 1107 1317 1628 1818 Gills Bay Road End - - - 0909 1113 1323 1634 1824 Canisbay - - - 0912 1117 1327 1638 1828 John o' Groats Bus Stand 0626 0643 0715 0918 1124 1334 1645 1835 Days of Operation Saturdays 80D 80 80 80 80 80 Thurso Olrig St Santander 0725 0905 1105 1305 1505 1755 Mount Pleasant Towerhill Road - 0910 1110 1310 1510 1800 Castletown Drill Hall 0735 0919 1119 1319 1519 1809 Dunnet Corner 0741 0925 1125 1325 1525 1815 Brough Letterbox - 0928 1128 1328 1528 1818 Greenvale Crossroads 0745 0933 1133 1333 1533 1823 Barrock - 0935 1135 1335 1535 1825 Greenvale Crossroads 0745 0937 1137 1337 1537 1827 Scarfskerry Baptist Church - 0941 1141 1341 1541 1831 Mey Post Office 0749 0947 1147 1347 1547 1837 Gills Bay Road End - 0953 1153 1353 1553 1843 Canisbay - 0957 1157 1357 1557 1847 John o' Groats Bus Stand - 1004 -

North Highlands North Highlands

Squam Lakes Natural Science Center’s North Highlands Wester Ross, Sutherland, Caithness and Easter Ross June 14-27, 2019 Led by Iain MacLeod 2019 Itinerary Join native Scot Iain MacLeod for a very personal, small-group tour of Scotland’s Northern Highlands. We will focus on the regions known as Wester Ross, Sutherland, Caithness and Easter Ross. The hotels are chosen by Iain for their comfort, ambiance, hospitality, and excellent food. Iain personally arranges every detail—flights, meals, transportation and daily destinations. Note: This is a brand new itinerary, so we will be exploring this area together. June 14: Fly from Logan Airport, Boston to Scotland. I hope that we will be able to fly directly into Inverness and begin our trip from there. Whether we fly through London, Glasgow or Dublin will be determined later in 2018. June 15: Arrive in Inverness. We will load up the van and head west towards the spectacular west coast passing by Lochluichart, Achnasheen and Kinlochewe along the way. We will arrive in the late afternoon at the Sheildaig Lodge Hotel (http://www.shieldaiglodge.com/) which will be our base for four nights. June 16-18: We will explore Wester Ross. Highlights will include Beinn Eighe National Nature Reserve, Inverewe Gardens, Loch Torridon and the Torridon Countryside Center. We’ll also take a boat trip out to the Summer Isles on Shearwater Summer Isle Cruises out of Ullapool. We’ll have several opportunities to see White-tailed Eagles, Golden Eagles, Black-throated Divers as well as Otters and Seals. June 19: We’ll head north along the west coast of Wester Ross and Sutherland past Loch Assynt and Ardvreck Castle, all the way up tp the north coast. -

Ipas in Scotland • 2

IPAs in Scotland • 2 • 5 • 6 • 3 • 4 • 15 • 10 • 11 • 14 • 16 • 12 • 13 • 9 • 7 • 8 • 17 • 19 • 21 • 26 • 29 • 23 • 25 • 27 31 • • 33 • 18 • 28 • 32 • 24 • 20 • 22 • 30 • 40 • 34 • 39 • 41 • 45 • 35 • 37 • 38 • 44 • 36 • 43 • 42 • 47 • 46 2 Contents Contents • 1 4 Foreword 6 Scotland’s IPAs: facts and figures 12 Protection and management 13 Threats 14 Land use 17 Planning and land use 18 Land management 20 Rebuilding healthy ecosystems 21 Protected areas Code IPA name 22 Better targeting of 1 Shetland 25 Glen Coe and Mamores resources and support 2 Mainland Orkney 26 Ben Nevis and the 24 What’s next for 3 Harris and Lewis Grey Corries Scotland’s IPAs? 4 Ben Mor, Assunt/ 27 Rannoch Moor 26 The last word Ichnadamph 28 Breadalbane Mountains 5 North Coast of Scotland 29 Ben Alder and Cover – Glen Coe 6 Caithness and Sutherland Aonach Beag ©Laurie Campbell Peatlands 30 Crieff Woods 7 Uists 31 Dunkeld-Blairgowrie 8 South West Skye Lochs 9 Strathglass Complex 32 Milton Wood 10 Sgurr Mor 33 Den of Airlie 11 Ben Wyvis 34 Colonsay 12 Black Wood of Rannoch 35 Beinn Bheigier, Islay 13 Moniack Gorge 36 Isle of Arran 14 Rosemarkie to 37 Isle of Cumbrae Shandwick Coast 38 Bankhead Moss, Beith 15 Dornoch Firth and 39 Loch Lomond Woods Morrich More 40 Flanders Moss 16 Culbin Sands and Bar 41 Roslin Glen 17 Cairngorms 42 Clearburn Loch 18 Coll and Tiree 43 Lochs and Mires of the 19 Rum Ale and Ettrick Waters 20 Ardmeanach 44 South East Scotland 21 Eigg Basalt Outcrops 22 Mull Oakwoods 45 River Tweed 23 West Coast of Scotland 46 Carsegowan Moss 24 Isle of Lismore 47 Merrick Kells Citation Author Plantlife (2015) Dr Deborah Long with editorial Scotland’s Important comment from Ben McCarthy. -

The Parish of Edderton During 1940 and World War II. After the Retreat from Dunkirk in June 1940, the British Army and Its Allie

The Parish of Edderton during 1940 and World War II. After the retreat from Dunkirk in June 1940, the British Army and its allies regrouped rapidly to take up defensive positions throughout the United Kingdom. In the North of Scotland the Army High Command was faced with the problem of preventing an effective German landing in the Highlands. Such a landing would have the objectives of isolating the naval bases in the Northern Isles and driving southwards to gain control of the many naval and air force bases around the Moray Firth. The key area in such a strategy was the Dornoch Firth which effectively cuts off Caithness and Sutherland from the rest of Scotland. The crossing of the firth itself was very difficult with its fast tides and shelving mudflats. The road bridge at Bonar and the railway bridge at Culrain were the only ways across that waterway unless the crossing was to be made in the difficult hill country away to the west. If the bridge at Bonar - and to a lesser extent the railway bridge at Invershin - could be held or destroyed, there was then no efficient way by which the tanks and vehicles of an attacking force could drive south out of Sutherland. The Dornoch Firth must have presented the same pattern of problems to the attacking Vikings and the defending Picts twelve hundred years earlier. In July 1940 the Army moved the Norwegian Brigade north to the Tain/Edderton area. They were supported by Royal Engineers and a battalion of the Pioneer Corps. The Engineers set to and prepared sites for demolition charges in both bridges and built concrete pill boxes that would command the approaches to the bridge. -

Builders Yard / Potential Residential Development

The Highlands Commercial Property Specialists Hotels Guesthouses BUILDERS YARD / POTENTIAL Licensed Retail RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT SITE Offices TULLOCH ROAD, BONAR BRIDGE Industrial HIGHLAND IV24 3EF Units Spacious Builders Yard located in the Highland village of Bonar Bridge with views across open country side Potential residential development site subject to planning permission on a site extending to circa 0.4 of an acre 17 Kenneth The subjects have availability to all amenity services and there are some buildings on Street site suitable for storage Inverness IV3 5NR Telephone 01463 714757 www.bedandbreakfastsales.co.uk Offers Around £140,000 (Freehold) DESCRIPTION SITE The sale comprise of an irregularly shaped but mainly The site extends to approximately 0.4 Acres. Site plans level site with rising ground to the rear of the subjects. will be available upon request Located within a mainly residential area of the village in an elevated position the site would lend itself to the SERVICES development of residences. The vendors have sought It is understood that services are located on the site. pre-planning advice which is available to interested parties upon request. PRICE Offers around £140,000 for the freehold of the subjects. LOCATION The development site is situated on an elevated site on VIEWING Tulloch Rd at the junction with Migdale Road in the All appointments to view must be made through the Village of Bonar Bridge in Sutherland. The site benefits vendors selling agents: from views over to the surrounding Countryside and to ASG Commercial the Kyle of Sutherland and the hills beyond. The village 17 Kenneth Street, Inverness IV3 5NR is situated at the junction of the A836 and A949. -

Caithness and Sutherland Proposed Local Development Plan Committee Version November, 2015

Caithness and Sutherland Proposed Local Development Plan Committee Version November, 2015 Proposed CaSPlan The Highland Council Foreword Foreword Foreword to be added after PDI committee meeting The Highland Council Proposed CaSPlan About this Proposed Plan About this Proposed Plan The Caithness and Sutherland Local Development Plan (CaSPlan) is the second of three new area local development plans that, along with the Highland-wide Local Development Plan (HwLDP) and Supplementary Guidance, will form the Highland Council’s Development Plan that guides future development in Highland. The Plan covers the area shown on the Strategy Map on page 3). CaSPlan focuses on where development should and should not occur in the Caithness and Sutherland area over the next 10-20 years. Along the north coast the Pilot Marine Spatial Plan for the Pentland Firth and Orkney Waters will also influence what happens in the area. This Proposed Plan is the third stage in the plan preparation process. It has been approved by the Council as its settled view on where and how growth should be delivered in Caithness and Sutherland. However, it is a consultation document which means you can tell us what you think about it. It will be of particular interest to people who live, work or invest in the Caithness and Sutherland area. In preparing this Proposed Plan, the Highland Council have held various consultations. These included the development of a North Highland Onshore Vision to support growth of the marine renewables sector, Charrettes in Wick and Thurso to prepare whole-town visions and a Call for Sites and Ideas, all followed by a Main Issues Report and Additional Sites and Issues consultation. -

Site Condition Monitoring for Otters (Lutra Lutra) in 2011-12

Scottish Natural Heritage Commissioned Report No. 521 Site condition monitoring for otters (Lutra lutra) in 2011-12 COMMISSIONED REPORT Commissioned Report No. 521 Site condition monitoring for otters (Lutra lutra) in 2011-12 For further information on this report please contact: Rob Raynor Scottish Natural Heritage Great Glen House INVERNESS IV3 8NW Telephone: 01463 725000 E-mail: [email protected] This report should be quoted as: Findlay, M., Alexander, L. & Macleod, C. 2015. Site condition monitoring for otters (Lutra lutra) in 2011-12. Scottish Natural Heritage Commissioned Report No. 521. This report, or any part of it, should not be reproduced without the permission of Scottish Natural Heritage. This permission will not be withheld unreasonably. The views expressed by the author(s) of this report should not be taken as the views and policies of Scottish Natural Heritage. © Scottish Natural Heritage 2015. COMMISSIONED REPORT Summary Site condition monitoring for otters (Lutra lutra) in 2011-12 Commissioned Report No. 521 Project No: 12557 and 13572 Contractor: Findlay Ecology Services Ltd. Year of publication: 2015 Keywords Otter; Lutra lutra; monitoring; Special Area of Conservation. Background 44 Special Areas of Conservation (SACs) for which otter is a qualifying interest were surveyed during 2011 and 2012 to collect evidence to inform an assessment of the condition of each SAC. 73 sites outside the protected areas network were also surveyed. The combined data were used to look for trends in the recorded otter population in Scotland since the first survey of 1977-79. Using new thresholds for levels of occupancy, and other targets agreed with SNH for the current report, the authors assessed 34 SACs as being in favourable condition, and 10 sites were assessed to be in unfavourable condition.