CONTENTS Digital.Pmd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Indian Ant:Iqijary

New Indian Ant:iqijary A monthly Journcl of Oriental Research in Archoeology, Art, Epigrophy, Ethnology, Folklore, Geography, History, Languages, Linguistics, Literature, Numismatics, Philoso phy, Religion and all subjects connected with lndology. VOLUME IV 1941-42 Edited by S. M. KATRE, M. A., Ph. D. ( London) and P. K. GODE, M. A. \NDz~ ......~"tl~ -- 3 \. ~ug.\983 KARNATAK PUBLISHING HOUSE BOMBAY ( INDIA) ;SOME NOTES ON THE HISTORY OF THE FIG (FICUS . CARICA) FROM FOREIGN AND INDIAN SOURCES By P. K. GODE, Poona. According to the history of the Fig (Ficus:Carica) recorded in the Ency r:lopoodiaBritannica,1 it was probably one of the earliest objects of cultivation. , There are frequent allusions to it in the Hebrew Scriptures. According to ; Herodotus it may have been unknown to the Persians in the days of the First Cyrus. Pliny mentions varieties of figs ani::11the plant played an im ..portant part in Latin myths. This history of the fig testifies to the high value • set upon the fruit by' the nations of antiquity but it says nothing about its · early existence in India or its importation to the Indian provinces known to the Greeks and Romans. According to Dr. AITCHISONIZ the Fig orFicus Carica was " probably a of Afghanistan and Persia "3 and it is indigenom; in the Badghis 1. Vide p. 228 of Vol. IX of the Fourteenth Edn. 1920. 11 From !he ease with which the nutritious fruit can be preserved it was probably one of the earliest · objects of cultivation ...... antiquity." I may note here the points in the para ,, noted above:- ( 1) Fig must have spread in remote ages over Agean and Levant ; (2) May have been unknown to Persians in the days of the First Cyrus according to a passage in Herodotus ; (3) Greeks received it from Caria (hence the name Ficus Carica) ; ( 4) Fig, the chief article of sustenance for the Greeks-laws to regulate their exportation-Attic Figs celebrated throughout the East-improved under Helenic Culture ; . -

Lady S.: Portuguese Medley Free

FREE LADY S.: PORTUGUESE MEDLEY PDF Jean van Hamme,Philippe Aymond | 48 pages | 07 Apr 2015 | CINEBOOK LTD | 9781849182225 | English | Ashford, United Kingdom Slings & Arrows Sitting at a restaurant, the guests are seen shifting in their seats, trying to get a glimpse of the singer. While Nadia has performed in Portugal in the past and has already established a career in Goa as a Fadista; this trip, which was meant to be for an academic purpose, ended up being a fantastic musical journey full of inspiration and rich experiences. Nadia had recently gone to Portugal to do a Portuguese language course at the University of Aveiro. I was told that I have a Portuguese soul with an exotic feel. It may be recalled Nadia had performed alongside the renowned Portuguese fadista "Marco Rodrigues and the famous Portuguese Fadista, Claudia Duarte, at their respective concerts held in Goa in the past. Rui Baceira. Being called to perform at the World Goa Day in Porto init gave her Lady S.: Portuguese Medley opportunity to sing at various Casas de Fado across Portugal, something she enjoyed performing this time around as well. A Seraulim girl and the granddaughter of Ponda, Nadia grew up in Lady S.: Portuguese Medley home Lady S.: Portuguese Medley always had music playing every day and she reminisces about the days that paved the path to who she is today. I also remember my dad training me to participate in my first Portuguese singing competition wherein he taught me Lady S.: Portuguese Medley song in a single day and I participated with it. -

Title Title Daily Current Affairs Capsule 19Th December 2020

Title Daily Current Affairs Capsule 19th DecemberTitle 2020 Pakistan approves chemical castration of sex offenders Pakistan has approved the chemical castration of rapists as part of sweeping new legislation sparked by outcry over the gang rape of a mother on a motorway. New laws approved by President Arif Alvi will see rape cases expedited through the courts and create the country’s first national sex offenders register. Pakistan is a deeply conservative and patriarchal nation where victims of sexual abuse often are too afraid to speak out, or where criminal complaints are frequently not investigated seriously. In September, protests erupted after a mother was raped on the side of the road in front of her children when her car broke down near Lahore. Goa Liberation Day 2020: 19 December Goa Liberation Day is observed on December 19 every year in India and it marks the day Indian armed forces freed Goa in 1961 following 450 years of Portuguese rule. The Portuguese colonised several parts of India in 1510 but by the end of the 19th-century Portuguese colonies in India were limited to Goa, Daman, Diu, Dadra, Nagar Haveli and Anjediva Island. The Goa liberation movement, which sought to end Portuguese colonial rule in Goa, started off with small scale revolts. The 36-hour military operation, conducted from December 18, 1961, was code-named ‘Operation Vijay’ meaning ‘Operation Victory,’ and involved attacks by the Indian Navy, Indian Air Force and Indian Army. All India Radio's weekly magazine 'Sanskrit Saptahiki' airs its 25th episode All India Radio's weekly magazine 'Sanskrit Saptahiki' aired its 25th episode. -

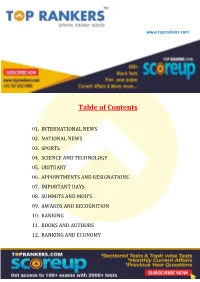

Table of Contents

www.toprankers.com Table of Contents 01. INTERNATIONAL NEWS 02. NATIONAL NEWS 03. SPORTS 04. SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 05. OBITUARY 06. APPOINTMENTS AND RESIGNATIONS 07. IMPORTANT DAYS 08. SUMMITS AND MOU’S 09. AWARDS AND RECOGNITION 10. RANKING 11. BOOKS AND AUTHORS 12. BANKING AND ECONOMY www.toprankers.com INTERNATIONAL NEWS India-Vietnamese Navy conducts PASSEX-2020 in South China Sea The Indian Navy and Vietnamese Navy undertook the naval passage exercise PASSEX in the South China Sea. The two-day exercise was conducted s part of efforts to boost maritime cooperation between the two countries. The Indian Naval Ship (INS) Kiltan took part in the exercise. INS Kiltan, reached Vietnam’s Nha Rong Port in Ho Chi Minh City, carrying humanitarian assistance to deliver 15 tonnes of relief material for flood-affected people under Mission Sagar-III. This mission of INS Kiltan is part of India’s Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR) assistance to Friendly Foreign Countries during the ongoing pandemic. Myanmar commissions submarine gifted by India Myanmar on Saturday inducted into its navy a submarine it received from India, which of late stepped up its maritime security cooperation with its neighbours as well as other nations in the Indo-Pacific region amid growing belligerence of China. The INS Sindhuvir, a Kilo-class submarine of the Indian Navy, has been renamed as the UMS Minye Theinkhathu. It was commissioned by the Myanmar Navy on the occasion of its 73rd anniversary. It is the first submarine to be acquired by the Myanmar Navy. India handed over the INS Sindhuvir to Myanmar three years after China provided two submarines to Bangladesh in 2017. -

Goa Liberation Day

Goa Liberation Day drishtiias.com/printpdf/goa-liberation-day-1 Why in News The Prime Minister of India greeted the people of Goa on Goa Liberation Day, which falls on 19th December every year. Key Points The day marks the occasion when the Indian armed forces freed Goa in 1961 from 450 years of Portuguese rule. The Portuguese colonised several parts of India in 1510 but by the end of the 19th-century Portuguese colonies in India were limited to Goa, Daman, Diu, Dadra, Nagar Haveli and Anjediva Island (a part of Goa). As India gained independence on 15th August, 1947, it requested the Portuguese to cede their territories but they refused. The Goa liberation movement started off with small scale revolts, but reached its peak between 1940 to 1960. In 1961, after the failure of diplomatic efforts with Portuguese, the Indian Government launched Operation Vijay and annexed Daman and Diu and Goa with the Indian mainland on 19th December. On 30th May 1987, the territory was split and Goa was formed. Daman and Diu remained a Union Territory. Hence, 30th May is celebrated as the Statehood Day of Goa. Goa 1/3 2/3 It is located on the southwestern coast of India within the region known as the Konkan, and geographically separated from the Deccan highlands by the Western Ghats. Capital: Panji. Official Language: Konkani. Konkani is one of the 22 languages from the Eight Schedule. It was added in the list along with Manipuri and Nepali by the 71st Amendment Act of 1992. Borders: It is surrounded by Maharashtra to the north and Karnataka to the east and south, with the Arabian Sea forming its western coast. -

List of Movements Recognized for Grant of Swatantrata Sainik Samman Pension

LIST OF MOVEMENTS RECOGNIZED FOR GRANT OF SWATANTRATA SAINIK SAMMAN PENSION. 1. Suez Canal Army Revolt in 1943 during Quit-India Movement & Ambala Cantt. Army Revolt in 1943. 2. Jhansi Regiment Case in Army (1940). The Rani of Jhansi Regiment was the Women's Regiment of the Indian National Army, with the aim of overthrowing the British Raj in colonial India. It was one of the all-female combat regiments of the Second World War. Led by Lakshmi Sahgal),the unit was raised in July 1943 with volunteers from the expatriate Indian population in South East Asia.The unit was named the Rani of Jhansi Regiment after Lakshmibai, Rani of Jhansi Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose announced the formation of the Regiment on 12 July 1943.Most of the women were teenage volunteers of Indian descent from Malayan rubber estates; very few had ever been to India.The initial nucleus of the force was established with its training camp in Singaporewith approximately a hundred and seventy cadets. The cadets were given ranks of non-commissioned officer or sepoy (private) according to their education. Later, camps were established inRangoon and Bangkok and by November 1943, the unit had more than three hundred cadets Training in Singapore began on 23 October 1943.The recruits were divided into sections and platoons and were accorded ranks of Non-Commissioned Officers and Sepoys according to their educational qualifications. These cadets underwent military and combat training with drills, route marches as well as weapons training in rifles, hand grenades, and bayonet charges. Later, a number of the cadets were chosen for more advanced training in jungle warfare in Burma.The Regiment had its first passing out parade at the Singapore training camp of five hundred troops on 30 March 1944. -

Kanhoji Angré and the Anglo-Portuguese Expedition of 1721

ISSN 2603-6096 East India Company Power Projection: Kanhoji Angré and the Anglo-Portuguese Expedition of 1721 (La proyección de la compañía de la India Oriental: Kanhoji Angré y la expedición anglo- portuguesa de 1721) Edward Teggin Trinity College Dublin Recibido: 03/12/2020; Aceptado: 03/03/2021; Abstract This article examines the causes and consequences of the 1721 Anglo-Portuguese expedition through the prism of regional geopolitics, power projection, and the balancing of power. The existing narrative of the expedition, presently very unclear and full of inconsistencies, shall be revised through the use of the private papers of Sir Robert Cowan, governor of Bombay (1729-34). The existing accounts have until now not adequately incorporated the key role played by Cowan. This article is, as such, an important revision in the wider history of European geopolitics on the west coast of India in the early eighteenth century. Keywords Colonial Bombay; Colonial Goa; Kanhoji Angré; Marathas; Power Projection Resumen Este artículo examina las causas y consecuencias de la expedición anglo-portuguesa de 1721 a través del prisma de la geopolítica regional, la proyección de poder y el equilibrio de fuerzas. La narración existente de la expedición, actualmente muy poco clara y llena de incoherencias ha sido revisada a partir de los documentos privados de Sir Robert Cowan, Edward Teggin gobernador de Bombay (1729-34). Hasta ahora, los relatos existentes no han incorporado adecuadamente el papel clave desempeñado por Cowan. Este artículo constituye, por tanto, una importante revisión en la historia más amplia de la geopolítica europea en la costa occidental de la India a principios del siglo XVIII. -

Political Structures in India.Pdf

mathematics HEALTH ENGINEERING DESIGN MEDIA management GEOGRAPHY EDUCA E MUSIC C PHYSICS law O ART L agriculture O BIOTECHNOLOGY G Y LANGU CHEMISTRY TION history AGE M E C H A N I C S psychology Political Structures In India Subject: POLITICAL STRUCTURE IN INDIA Credits: 4 SYLLABUS Early State Formation Pre-State to State, Territorial States to Empire, Polities from 2nd Century B.C. to 3rd Century A.D., Polities from 3rd Century A.D. to 6th Century A.D State in Early Medieval India Early Medieval Polities in North India, 7th to 12th Centuries A.D., Early Medieval Polities in Peninsular India 6th to 8th Centuries A.D., Early Medieval Polities In Peninsular India 8th To 12 Centuries A.D. Administrative and Institutional Structures Administrative and Institutional Structures in Peninsular India, Administrative and Institutional Systems in North India, Law and Judicial Systems, State Under the Delhi Sultanate, Vijayanagar, Bahmani and other Kingdoms, The Mughal State, 18th Century Successor States Colonization-Part I The Eighteenth Century Polities, Colonial Powers Portuguese, Dutch and French, The British Colonial State, Princely States Colonization Part II Ideologies of the Raj, Activities, Resources, Extent of Colonial Intervention Education and Society, End of the Colonial State-establishment of Democratic Polity. Suggested Reading: 1. Social Change and Political Discourse in India: Structures of Power, Movements of Resistance Volume 4: Class Formation and Political Transformation in Post-Colonial India by T. V. Sathymurthy, T. V. Sathymurthy 2. Political parties and Collusion : Atanu Dey 3. The Indian Political System : Mahendra Prasad Singh, Subhendu Ranjan Raj CHAPTER 1 Early State Formation STRUCTURE Learning objectives Pre-state to state Territorial states to empire Polities from 2nd century BC. -

Bharatiya Manyaprad International Journal of Indian Studies

Bharatiya Manyaprad International Journal of Indian Studies Vol. 6 Annual April-May 2018 Executive Editor Sanjeev Kumar Sharma FORM-IV 1. Place of Publication : Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, Ahmedabad Kendra 2. Periodicity : Annual 3. Printer’s Name : Dr Neerja A Gupta Nationality : Indian Address : II Floor Rituraj Apartment Opp. Rupal Flats, Nr St. Xavier’s Loyola Hall Navrangpura, Ahmedabad 4. Publishers’ Name : Dr Neerja A Gupta Nationality : Indian Address : II Floor Rituraj Apartment Opp. Rupal Flats, Nr St. Xavier’s Loyola Hall Navrangpura, Ahmedabad 5. Editor’s Name : Dr Neerja A Gupta Nationality : Indian Address : II Floor Rituraj Apartment Opp. Rupal Flats, Nr St. Xavier’s Loyola Hall Navrangpura, Ahmedabad 6. Name and Address of the: Nil Individuals who own the Newspaper and partners/ Shareholders holding more than one percent of the Capital I, Neerja A Gupta, hereby declare that the particulars are true to my knowledge and belief. Sd. (Neerja A Gupta) Bharatiya Manyaprad International Journal of Indian Studies Vol. 6 Annual April-May 2018 Contents Editorial v 1. Science in Jain Canonical Literature 7 Ajay Kumar Singh 2. Media, Platform for Self-Expression and Ethnic Identity: Case of Indian Diaspora 13 Wisdom Peter Awuku & Sonal Pandya 3. Migration and Enclaves System: A Study on North Bengal of India 25 Sowmit C. Chanad & Neerja A. Gupta 4. Philosophy Subject vis-s-vis Philosophy Works: Contemporary Need and Relevance 34 Sushim Dubey 5. Satyagraha and Nazism: Two most Contradictory Movements of the Century 45 Apexa Munjal Fitter 6. The Mahabharata: A Glorious Literary Gift to the World from Bharata 65 Virali Patoliya & Vidya Rao 7. -

Operation Vijay-Liberation of Goa

Operation Vijay-Liberation of Goa December 26, 2020 In news Goa Liberation Day is observed on December 19 every year in India Background The Portuguese colonized several parts of India in 1510 but by the end of the 19th-century Portuguese colonies in India were limited to Goa, Daman, Diu, Dadra, Nagar Haveli and Anjediva Island. On August 15, 1947, when India gained its Independence, Goa was still under the Portuguese rule. The Portuguese refused to give up their hold over Goa and other Indian territories. Following a myriad of unsuccessful negotiations and diplomatic efforts with the Portuguese, the former prime minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru, decided that military intervention was the only option. The 36-hour military operation, conducted from December 18, 1961, was code-named ‘Operation Vijay’ meaning ‘Operation Victory,’ and involved attacks by the Indian Navy, Indian Air Force, and Indian Army. Ram Manohar Lohia’s effort In June 1946, Ram Manohar Lohia, an Indian Socialist leader, entered Goa on a visit to his friend, Julião Menezes, a nationalist leader, who had founded the Gomantak Praja Mandal in Bombay and edited the weekly newspaper Gomantak. Ram Manohar Lohia advocated the use of non-violent Gandhian techniques to oppose the government. On 18 June 1946, the Portuguese government disrupted a protest against the suspension of civil liberties in Panajiorganised by Lohia, Cunha and others including Purushottam Kakodkar and Laxmikant Bhembre in defiance of a ban on public gatherings, and arrested them His efforts were followed by diplomatic efforts by Indian government which failed and led to armed action against the Portuguese rule About Operation Vijay: The liberation of Goa Operation Vijay marks the day Indian armed forces(with armed action)freed Goa, Daman & Diu in 1961 following 450 years of Portuguese rule. -

General Population Tables and Primary Census Abstract, Part II-A

CENSUS OF INDIA 1981 SERIES-29 GOA" DAMAN & DIU PART II-A GENERAL POPULATION TABLES AND PART II-B PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT S.K.GANDHE Of the Indian Economic Service, Director of Census Operations, Goa. Dam'm &: Pi" I I ::J (f) 2 i i -c o <It • iii i i 0.. C oCS > « I I "") o z 2: « <C ::2: <C 1: C 0 .. E "t< a: :.! «2 ..t- o( z 15 0 z ;;; ":> j O~ ;;;) 0« ,: D! 0( z i I " ~ ~ .. I;; I K A N T A K A R «o (!) : z \l: 0', CD W a:: 1981 CENSUS PUBLICATIONS OF GOA, DAMAN & DIU (All the Census Publications of this Union Territory will bear Series No. 29) Central Government Publications Part I Administration Report(for official:useonly) Part LA Administration Report-EnmeHtion. Part I.B A (1 ministration Report-T<I bulation. Part II G-lneral Pdpuation Ta bles Part II.A General Population Tables Part n.B Primary Census Abstract. Pact III General Economic Tables Part III.A B·Sedes Tables of first priority (Table B.t t(1 B.IO). Part III.B B·Series Tables of second priority (Tables B.Il to B.12)· Part IV Social and Cultural Tables Part IV. A C-Series Tables of first priority (1abks ~C-l to C-6) Part IV.B C-Series Tables of second priority (Tables C-7 to C·lO ). Part V Migration Tables Part V.A D·Series Tables of first priority (Tables D·l to D·4) Part V.B D·Series Tables of second priority (Tables D·5 to 0.13). -

Mitragotri V R 1992.Pdf

A SOCIO-CULTURAL HISTORY OF GOA FROM THE BHOJAS TO THE VIJAYANAGARA By V. R. Mitragotri M.A. (History), M.A. (Archaeology), Post Graduate Diploma in Archaeology For the Degree of Ph. D. (History) of the Goa University Under the guidance of Dr. K. M. Mathew Department of History Goa University GOA UNIVERSITY TALEIGAO PLATEAU GOA 403 005. V. R. MITRAGOTRI, M. A., Departthent of History, Taleigao Plateau, Goa University, Goa. STATEMENT BY THE CANDIDATE I hereby state that the thesis for the Ph. D. Degree on " SOCIO - CULTURAL HISTORY OF GOA FROM THE BHOJASTO THE yr VIJAYANAGARA" is my original work and that it has not previously formed the basis for the award of any Degree, Diploma, Associateship, Fellowship or any other similar title. Place: GOA Signature of the Candidate Date : ( V. R. Mitragotri ) Counters]. ned Dr. K. M. athew, M. A. Ph. D. Head of the Department, Department of History, Goa University, Taleigao Plateau, Goa. I PREFACE During the sixteen'years from 1977, as an Assistant Superintending Archaeologist in the Directorate of Archives, . Archaeology and Muscum, , I have travelled throughout Goa. Through my work involved in the Directorate, I realised that there is no work exclusively devoted to Socio-Cultural History • of Goa pertaining to Pre-Portuguese period. In Goa sources in epigraphy. are available from c. 400 A.D. Hence the Socio- Cultural History of Goa from the Bhojas to the Vijayanagara was selected. Dr. K. .M. Mathew of the History Department of • , Goa University accepted me as the student. I am beholden for his constant encouragement and valuable guidance ih completing this work.