Download File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to 20Th-Century Non- Domestic Buildings and Public Places In

th Guide to 20 -century Non- Domestic Buildings and Public Places in Worcestershire Published 2020 as part of NHPP7644 Adding a new layer: th 20 -century non-domestic buildings and public places in Worcestershire Authorship and Copyright: This guidance has been written by Emily Hathaway of Worcestershire County Council Archive and Archaeology Service and Jeremy Lake, Heritage Consultant with contributions by Paul Collins, Conservation Officer, Worcester City Council Published: Worcestershire County Council and Historic England 2020 Front Cover Image: Pre-fabricated Village Hall, Pensax. Images: © Worcestershire County Council unless specified. Publication impeded until October 2020, due to the impact of the COVID-19 global pandemic. NHPP7644: GUIDE TO 20th CENTURY NON-DOMESTIC BUILDINGS AND PUBLIC PLACES IN WORCESTERSHIRE CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………………………………………………1 1.1 The planning and legislative background…………………………………………………………..2 1.2 Heritage assets and Historic Environment Records…..……………………………………….3 2. TYPES OF 20TH CENTURY HERITAGE IN WORCESTERSHIRE………………………………………4 2.1 Agricultural and Subsistence (including Allotments) …………………………..………………4 2.2 Civil…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..11 2.3 Commemorative (including Public Art).…………………………………………………………….19 2.4 Commercial……………………………………………………………………………………………………….23 2.5 Communications……………………………………………………………………………………………….31 2.6 Defence…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….36 2.7 Education………………………………………………………………………………………………………….41 2.8 Gardens, Parks and -

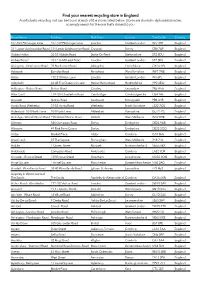

Find Your Nearest Recycling Store in England a Soft Plastic Recycling Unit Can Be Found at Each of the Stores Listed Below

Find your nearest recycling store in England A soft plastic recycling unit can be found at each of the stores listed below. Stores are shared in alphabetical order, so simply search for the one that’s closest to you. Store Name Address Post Town County Post Code Country 107-109 Pitshanger Lane 107-109 Pitshanger Lane London Greater London W5 1RH England 311 Lower Addiscombe Road 311 Lower Addiscombe Road Croydon Surrey CR0 7AF England Abbey Hulton 53-55 Abbots Road Stoke-On-Trent Staffordshire ST2 8DU England Abbey Wood 103-116 McLeod Road London Greater London SE2 0BS England Abingdon - Northcourt Road 39 Northcourt Road Abingdon Oxfordshire OX14 1PJ England Ackworth Barnsley Road Pontefract West Yorkshire WF7 7NB England Acton 192-210 Horn Lane London Greater London W3 6PL England Adeyfield 46-48 The Queens Square Hemel Hempstead Hertfordshire HP2 4EW England Adlington - Bolton Road Bolton Road Chorley Lancashire PR6 9NA England Ailsa Court 179-185 Chesterton Road Cambridge Cambridgeshire CB4 1AF England Ainsdale Station Road Southport Merseyside PR8 3HR England Ainsty Road Wetherby 51-55 Ainsty Road Wetherby North Yorkshire LS22 7QS England Aldershot - 264 North Lane 264 North Lane Aldershot Hampshire GU12 4TJ England Aldridge - Walsall Wood Road 198 Walsall Wood Road Walsall West Midlands WS9 8HB England Allenton 840 Osmaston Road Derby Derbyshire DE24 9AB England Allestree 49 Park Farm Centre Derby Derbyshire DE22 2QQ England Alston Market Place Alston Cumbria CA9 3HS England Alvechurch 25 The Square Birmingham West Midlands B48 7LA England Amble 1 Queen Street Morpeth Northumberland NE65 0BX England Ambleside Compston Road Ambleside Cumbria LA22 9DR England Ancaster - Ermine Street 139 Ermine Street Grantham Lincolnshire NG32 3QN England Angel Square 1 Angel Square Manchester Greater Manchester M60 0AG England Ansdell - Woodlands Road 38-40 Woodlands Road Lytham St. -

Registered Pharmacies 2019-07-12

The list of pharmacies registered to sell PPCs on our behalf is sorted alphabetically in postcode order. 0 NAME PREMISES ADDRESS 1 PREMISES ADDRESS 2 PREMISES ADDRESS 3 PREMISES ADDRESS 4 POSTCODE LLOYDS PHARMACY SAINSBURYS, EVERARD CLOSE ST ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL1 2QU BOOTS UK LIMITED 9 ST PETERS STREET ST.ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL1 3DH FREEMAN GRIEVES LTD 111-113 ST PETERS STREET ST.ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL1 3ET LLOYDS PHARMACY PARKBURY HOUSE ST PETER ST ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL1 3HD IMED PHARMACY 67 HATFIELD ROAD ST ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL1 4JE ST ALBANS PHARMACY 197 CELL BARNES LANE ST ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL1 5PX LLOYDS PHARMACY SAINSBURYS, BARNET ROAD LONDON COLNEY ST ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL2 1AB LLOYDS PHARMACY 17 RUSSELL AVENUE ST ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL3 5ES NORMANDY PHARMACY 52 WAVERLEY ROAD ST ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL3 5PE CROWN PHAMRACY 65 HIGH STREET REDBOURN ST ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL3 7LW MANOR PHARMACY (WHEATHAMPSTEAD) LTD 2 HIGH STREET WHEATHAMPSTEAD HERTFORDSHIRE AL4 8AA BOOTS UK LIMITED 23-25 HIGH STREET HARPENDEN HERTFORDSHIRE AL5 2RU LLOYDS PHARMACY 40 HIGH STREET WELWYN GARDEN CITY HERTFORDSHIRE AL6 9EQ LLOYDS PHARMACY 84 HALDENS WELWYN GARDEN CITY HERTFORDSHIRE AL7 1DD BOOTS UK LIMITED 65 MOORS WALK WELWYN GARDEN CITY HERTFORDSHIRE AL7 2BQ BOOTS UK LIMITED 31 COLE GREEN LANE WELWYN GARDEN CITY HERTFORDSHIRE AL7 3PP PEARTREE PHARMACY 110 PEARTREE LANE WELWYN GARDEN CITY HERTFORDSHIRE AL7 3UJ BOOTS UK LIMITED 126 PEARTREE LANE WELWYN GARDEN CITY HERTFORDSHIRE AL7 3XY BOOTS UK LIMITED 31 THE HOWARD CENTRE WELWYN GARDEN -

South Worcestershire Employment Land Monitor (April 2010)

Sustainable Economic Development Monitor, April 2010 Sustainable Economic Development Monitor 2010 Information presented in this study represents data monitored from the period: 1St April 2009 to 31 st March 2010 This study also includes analysis of Malvern Hills District’s rolling five-year reservoir of employment land Sustainable Economic Development Monitor, April 2010 Sustainable Economic Development Monitor, April 2010 CONTENTS PART A PAGE 1.0 INTRODUCTION 6 1.1 What is Economic Development 6 1.2 Planning Policy Framework 7 1.2 Economic Profile 8 1.3 Employment Land Availability 8 2.0 METHODOLOGY 9 3.0 PLANNING POLICY FRAMEWORK 11 3.1 National 11 3.2 Regional and Sub-regional 14 4.0 AN ECONOMIC PROFILE OF THE SOUTH 23 WORCESTERSHIRE AREA 5.0 MALVERN HILLS DISTRICT EMPLOYMENT LAND 27 AVAILABILITY MONITOR 5.1 Malvern Hills District Employment Completions 27 2009 to 2010 5.2 Malvern Hills District Employment Land Position at 36 April 2010 5.3 Progress Towards Meeting Employment Targets 38 and Five-Year Reservoir of Employment Land for Malvern Hills District 6.0 WORCESTER CITY EMPLOYMENT LAND 43 AVAILABILITY MONITOR 6.1 Worcester City Employment Completions 2009 to 43 2010 6.2 Worcester City Employment Land Position at April 53 Sustainable Economic Development Monitor, April 2010 2010 6.3 Progress Towards Meeting Employment Targets 56 and Five-Year Reservoir of Employment Land for Worcester City 7.0 WYCHAVON DISTRICT EMPLOYMENT LAND 61 AVAILABILITY MONITOR 7.1 Wychavon District Employment Completions 2009 61 to 2010 7.2 Wychavon District -

Registered Pharmacies 2017-02-28

The list of pharmacies registered to sell PPCs on our behalf is sorted alphabetically in postcode order. 0 NAME PREMISES ADDRESS 1 PREMISES ADDRESS 2 PREMISES ADDRESS 3 PREMISES ADDRESS 4 BOOTS UK LIMITED 9 ST PETERS STREET ST.ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL1 3DH FREEMAN GRIEVES LTD 111-113 ST PETERS STREET ST.ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL1 3ET IMED PHARMACY 67 HATFIELD ROAD ST ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL1 4JE MANOR PHARMACY (WHEATHAMPSTEAD) LTD 2 HIGH STREET WHEATHAMPSTEAD HERTFORDSHIRE AL4 8AA BOOTS UK LIMITED 23-25 HIGH STREET HARPENDEN HERTFORDSHIRE AL5 2RU BOOTS UK LIMITED 65 MOORS WALK WELWYN GARDEN CITY HERTFORDSHIRE AL7 2BQ BOOTS UK LIMITED 31 COLE GREEN LANE WELWYN GARDEN CITY HERTFORDSHIRE AL7 3PP PEARTREE PHARMACY 110 PEARTREE LANE WELWYN GARDEN CITY HERTFORDSHIRE AL7 3UJ BOOTS UK LIMITED 126 PEARTREE LANE WELWYN GARDEN CITY HERTFORDSHIRE AL7 3XY BOOTS UK LIMITED 31 THE HOWARD CENTRE WELWYN GARDEN CITY HERTFORDSHIRE AL8 6HA BOOTS UK LIMITED 47 TOWN CENTRE HATFIELD HERTFORDSHIRE AL10 0LD BOOTS UK LIMITED 2A BRINDLEY PLACE BIRMINGHAM B1 2JB BOOTS UK LIMITED UNIT MSU 10A NEW BULL RING SHOP CTR BIRMINGHAM WEST MIDLANDS B2 4BE BOOTS UK LIMITED 102 NEW STREET BIRMINGHAM WEST MIDLANDS B2 4HQ BOOTS UK LIMITED 66 HIGH STREET BIRMINGHAM WEST MIDLANDS B4 7TA BOOTS UK LIMITED 71 PERSHORE ROAD EDGBASTON BIRMINGHAM WEST MIDLANDS B5 7NX NUCARE HEALTHCARE LTD VICTORIA ROAD MEDICAL CTR 229-233 VICTORIA ROAD ASTON BIRMINGHAM B6 5HP SODHA P 31 REVESBY WALK NECHELLS BIRMINGHAM WEST MIDLANDS B7 4LG J DOCTER LTD BLOOMSBURY VILLAGE CENTRE 67 RUPERT STREET NECHELLS -

Employment Land Monitor 2015

Employment Land Monitor 2015 Information presented in this report represents data monitored from the period: 1St April 2014 to 31st March 2015 Contents Page 1. Introduction 3 2. Employment Land Development 4 3. Land Type 7 4. Available Employment Floorspace 8 5. Worcester Employment Land Supply at April 2015 9 6. Provision and Rolling Five-Year Reservoir of 17 Employment Land 7. Conclusion 22 Employment Land Monitor Schedules 2014/15 23 Schedule 1 - Brownfield Land identified in the Adopted 24 Local Plan for Employment Schedule 2 - Greenfield Land identified in the Adopted 25 Local Plan for Employment Schedule 3 - Commitments for Employment Uses 26 including Allocated Sites Schedule 4 - Land developed for Industrial/Employment 28 Use 1st April 1996 – 31st March 2015 Schedule 5 - Total land developed for Employment Uses 41 1st April 1996 – 31st March 2015 Schedule 6 - Permissions included in the last monitoring 42 report which had expired by 31st March 2015 Schedule 7 - Employment Sites Larger than 0.1 Hectare 43 Lost to Other Uses Since 1996 Schedule 8 - South Worcestershire Development Plan 45 Employment Site Allocations including Current Local Plan Allocations Page 1 Tables Page Table 1 Employment Land in Worcester 1996-2015 5 Table 2 Status of Local Plan Sites 11 Table 2a Approved non B use class development on allocated 12 employment sites Table 3 Worcester Local Plan Employment Land Supply 31st 13 March 2015 Table 4 South Worcestershire Development Plan Wider 15 Worcester Employment Land Supply 31st March 2015 Table 5 South Worcestershire Development Plan Worcester 16 City Employment Land Supply 31st March 2015 Table 6 Worcester Five Year Reservoir of Employment Land 20 Page 2 1. -

Worcester Town Investment Plan Appendix D: Detailed Project Summary Report January 2020

Worcester Town Investment Plan Appendix D: Detailed Project Summary Report January 2020 Mott MacDonald Ground floor Royal Liver Building Pier Head Liverpool L3 1JH United Kingdom T +44 (0)151 482 9910 mottmac.com Worcester Town Investment Plan Appendix D: Detailed Project Summary Report January 2020 Mott MacDonald Limited. Registered in England and Wales no. 1243967. Registered office: Mott MacDonald House, 8-10 Sydenham Road, Croydon CR0 2EE, United Kingdom Mott MacDonald | Worcester Town Investment Plan Appendix D: Detailed Project Summary Report Issue and Revision Record Revision Date Originator Checker Approver Description 1A 08/01/2021 A Bennett S Donlon V Hurst First Draft Document reference: 421824 | 1 | A Information class: Standard This document is issued for the party which commissioned it and for specific purposes connected with the above- captioned project only. It should not be relied upon by any other party or used for any other purpose. We accept no responsibility for the consequences of this document being relied upon by any other party, or being used for any other purpose, or containing any error or omission which is due to an error or omission in data supplied to us by other parties. This document contains confidential information and proprietary intellectual property. It should not be shown to other parties without consent from us and from the party which commissioned it. 421824 | 1 | A | January 2020 Mott MacDonald | Worcester Town Investment Plan Appendix D: Detailed Project Summary Report Contents 1 Introduction -

WORCESTER MUNICIPAL CHARITIES (CIO) TRUSTEES' ANNUAL REPORT 1St JANUARY – 31St DECEMBER 2020

A R 2 ( ) 0 WORCESTER MUNICIPAL CHARITIES CIO 2 Registered Charity No.1166931 • Member of the Almshouse Consortium 0 Registered Housing Association No.4855 • Member of the Almshouse Association No.159 Predecessor charities founded 1559 & 1836 TRUSTEES' ANNUAL REPORT 1st JANUARY – 31st DECEMBER 2020 This is the fourth year’s Annual Report of the Charity which was created specifically by the Trustees as the successor Charity for Worcester Municipal Exhibitions Foundation and Worcester Consolidated Municipal Charity in 2016. The Charity is a “Charitable Incorporated Organisation” but has very similar objects to the two unincorporated predecessor charities which it replaced. The Trustees present their report and the audited financial statements of the Charity for the twelve months’ period ended 31st December 2020 (“The Period”). The Trustees have adopted the provisions of the Statement of Recommended Practice (SORP): "Accounting by Registered Social Housing Providers Update 2018” along with Financial Reporting Standard 102 in preparing the report and financial statements of the Charity. The financial statements for the Charity have been prepared in accordance with the accounting policies set out in the notes to the accounts and comply with the Statements of Recommended Practice. Registered Office All enquiries to: Worcester Municipal Charities (CIO) Kateryn Heywood House Berkeley Court, The Foregate Worcester WR1 3QG Telephone: 01905 317117 Fax: 01905 619979 Office Administration: Maggie Inglis, Sarah Bradnick, Margaret Green Email: [email protected] -

Annual Monitoring Report

What is an Annual Inside this Monitoring Report? document: Monitoring and evaluation are both vitally important if councils are to demonstrate their Introduction………..…..…..2 effectiveness and value for money. Recent changes to Government Legislation now mean Profile of Worcester….…...4 councils are responsible for their own perfor- mance management and are accountable to Population………...…..……5 local communities rather than central govern- ment. Economy…………......……..6 Planning delivers the council’s objectives for Employment Land.….…..….8 Worcester through the planning policy and development management processes. Worcester City Council Housing……………………..9 The AMR assesses and demonstrates the Natural Environment……..14 effectiveness of Worcester’s planning policies, Annual Monitoring monitors Worcester’s City Council’s perfor- Built Environment………...16 mance in implementing Local Plan policies Report 2010/11 and monitors the council’s performance in Transport………………….18 producing and implementing Local Develop- Appendix…………………..19 ment Framework policy. Worcester City Council Orchard House Complex Farrier Street Worcester WR1 3BB Phone: 01905 722233 E-mail: [email protected] achieved (Sections 13 and 35 of the Planning and Introduction Compulsory Purchase Act 2004). Executive Summary The AMR is helpful in that it looks to establish the value added by Development Management, Con- he primary purpose of this docu- servation and Enforcement activity. For example, a n 2010 Worcester produced a joint AMR ment is to share the performance statistic like the number of affordable houses de- with Wychavon and Malvern Hills districts. and achievements of the planning livered would translate into the outcome of The purpose of this was feed in to the joint service with the local community. -

Sustainability Appraisal of the South Worcestershire Development Plan Review

Sustainability Appraisal of the South Worcestershire Development Plan Review Scoping Report August 2018 Sustainability Appraisal of the South Worcestershire Development Plan Review Scoping Report LC-342 Document Control Box Client Malvern Hills District Council Sustainability Appraisal of the South Worcestershire Development Plan Review: Scoping Report Title Report Filename LC-361_SWDP_SA_Scoping_8_030818JE.docx Date August, 2018 Author CW Reviewed JE Approved ND Front cover: Bredon Hill from Broadway Tower by Richard Giddy About this report & notes for readers Lepus Consulting Ltd (Lepus) has prepared this report for effects of the South Worcestershire Development Plan the use of Malvern Hills District Council on the behalf of Review and meets the requirements of the SEA Directive. It South Worcestershire Councils. There are a number of is not intended to be a substitute for Environmental Impact limitations that should be borne in mind when considering Assessment (EIA) or Appropriate Assessment (AA). the conclusions of this report. No party should alter or change this report whatsoever without written permission from Lepus. Client comments can be sent to Lepus using the following address. © Lepus Consulting Ltd 1 Bath Street, Cheltenham This Scoping Report is based on the best available information, including that provided to Lepus by the Council Gloucestershire and information that is publicly available. No attempt to GL50 1YE verify these secondary data sources has been made and they have assumed to be accurate as published. This Telephone: -

Worcester West • Claines (North)

Contents Page 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 2. Summary ............................................................................................................................................................... 5 2.1 Background ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 2.2 Consultation Material ................................................................................................................................................................... 6 2.3 Key Conclusions ............................................................................................................................................................................. 7 2.4 Worcestershire County Council Local Members .................................................................................................................... 7 2.5 Worcestershire District Members ............................................................................................................................................. 8 2.6 Local Government Officers ......................................................................................................................................................... 8 2.7 Statutory Stakeholders, Regional Bodies & Operators ....................................................................................................... -

Planning Committee

PLANNING COMMITTEE AGENDA Planning Officers will be available in the Guildhall from 1.00pm to respond to questions on the detail of applications from Members. The late papers will be available at that time. Date: Thursday, 22nd August, 2013 Time: 1.30 pm Venue: Guildhall PLANNING COMMITTEE Members o f the C ommittee :- Chairman: Councillor David Wilkinson (C) Vice -Chairman: Councillor Pa tricia Agar (L) Councillor Alan Amos (L) Councillor Andrew Roberts (C) Councillor Roger Berry (L) Councillor Robert Rowden (C) Councillor Lynn Denham (L) Councillor Aubrey Tarbuck (C) Councillor Paul Denham (L) Councillor Dr David Tibbutt (C) Councillor Derek Prodger MBE (C) Councillor Geoff Williams (L) C = Conservative L = Labour Information for Members of the Public Access to the Guildhall is via the front entrance in the High Street. The nearest car park is Copenhagen Street (pay and display). If you are a wheelchair user or have restricted mobility, access to the Guildhall can be gained either through the door on the right side of the forecourt as you face the Guildhall, or through the sliding doors at the rear of the Guildhall. There is dedicated disabled parking space at the rear (access via Copenhagen Street). Most meetings are held on the ground floor, which can be reached by using a lift. If you are a wheelchair user or have restricted mobility and you wish to attend a meeting, please telephone or email the officer mentioned below in advance and we will make any necessary arrangements to assist your visit. Part I of the Agenda includes items for discussion in public.