Changing Security Perceptions in Turkish-Iranian Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

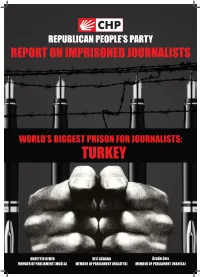

Report on Imprisoned Journalists

REPUBLICAN PEOPLE’S PARTY REPORT ON IMPRISONED JOURNALISTS WORLD’S BIGGEST PRISON FOR JOURNALISTS: TURKEY NURETTİN DEMİR VELİ AĞBABA ÖZGÜR ÖZEL MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT (MUĞLA) MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT (MALATYA) MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT (MANİSA) REPUBLICAN PEOPLE’S PARTY PRISON EXAMINATION AND WATCH COMMISSION REPORT ON IMPRISONED JOURNALISTS WORLD’S BIGGEST PRISON FOR JOURNALISTS: TURKEY NURETTİN DEMİR VELİ AĞBABA ÖZGÜR ÖZEL MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT (MUĞLA) (MALATYA) (MANİSA) CONTENTS PREFACE, Ercan İPEKÇİ, General Chairman of the Union of Journalists in Turkey ....... 3 1. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................... 11 2. JOURNALISTS IN PRISON: OBSERVATIONS AND FINDINGS .................. 17 3. JOURNALISTS IN PRISON .......................................................................... 21 3.1 Journalists Put on Trial on Charges of Committing an Off ence against the State and Currently Imprisoned ................................................................................ 21 3.1.1Information on a Number of Arrested/Sentenced Journalists and Findings on the Reasons for their Arrest ........................................................................ 21 3.2 Journalists Put on Trial in Association with KCK (Union of Kurdistan Communities) and Currently Imprisoned .................................... 32 3.2.1Information on a Number of Arrested/Sentenced Journalists and Findings on the Reasons for their Arrest ....................................................................... -

M. Fethullah Gülen's Understanding of Sunnah

M. FETHULLAH GÜLEN’S UNDERSTANDING OF SUNNAH Submitted by Mustafa Erdil A thesis in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Theology Faculty of Theology and Philosophy Australian Catholic University Research Services Locked Bag 4115 Fitzroy, Victoria 3065 Australia 23 JULY 2016 1 | P a g e STATEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP AND SOURCES This thesis contains no material published elsewhere or extracted in whole or in part from a thesis by which I have qualified for or been awarded another degree or diploma. No other person’s work has been used without due acknowledgement in the main text of the thesis. This thesis has not been submitted for the award of any degree or diploma in any other tertiary institution. All research procedures in the thesis received the approval of the relevant Ethics/Safety Committees (where required). Mustafa Erdil 23 JULY 2016 Signature: ABSTRACT The aim and objective of this study is to highlight the importance of and the status of hadith in Islam, as well as its relevance and reference to sunnah, the Prophetic tradition and all that this integral source of reference holds in Islam. Furthermore, hadith, in its nature, origin and historical development with its close relationship with the concept of memorisation and later recollection came about after the time of Prophet Muhammad. This study will thus explore the reasons behind the prohibition, in its initial stage, with the authorisation of recording the hadiths and its writing at another time. The private pages of hadith recordings kept by the companions will be sourced and explored as to how these pages served as prototypes for hadith compilations of later generations. -

Turan Dursun

21.03.2010 Din Bu 1 1.sayfadan 50. sayfaya TURAN DURSUN Tabu Can Çekişiyor DİN BU I. KİTAP İÇİNDEKİLER Yazarın önsözü 9 Prof. Dr. İlhan Arsel'in önsözü 11 "Muhammed'in Cinsel Hayatı" 16 İslam ve Şiddet 48 Nasıl Yakıldım? 61 Rüşvetle Müslüman Olanlar 78 Kur'an'm Orijinalleri Yakıldığı İçin Şimdi Yok 78 islamcıların Pehlivanı Yok 90 Ayetler Uydurma mı? 101 "Şeytan Ayetleri" Islamın Gerçeği 103 Kara Sesli Karanlık 108 Muhammed'e Göre Kadın "Uğursuz"dur 110 İnandırmak İçin Kur'andaki Tanrı'nın Andiçmeleri 113 Büyü ve Muhammed'in Büyülenmişliği 116 islam'a Göre "Millet" 119 Kurban 122 "Kor'an Mucizeleri" 128 Muhammed'in Doktorluğu I 131 Muhammed'in Doktorluğu II 134 Muhammed'in Doktorluğu III 138 Kur'an'm Tanrısı Nerede? 141 gencalevilerharekati.eu/…/Din_Bu 1 Tu… 1/47 21.03.2010 Din Bu 1 Tanrı'nın Tahtı, Sarayı 8 Dağ Keçisinin Sırtında 144 "Gök Sofrası" 147 Tevrat, İncil, Kur'an 150 Tann'nın Biçimi ve Boyu 153 Kur'an'daki Tann'nın İnsanları Ayırma Politikası 156 Kur'an'm Tanrı'smın Elindeki Terazi 159 Kur'an'daki Tann'nın Beddualan 162 insanı Hayvana Dönüştürme Cezası 165 "inşallah" 168 islam'ın Tannsı Akıllı mı? 171 "Tann Bildi-Anladı ki..." 174 Görüş Değiştiren "Tann" 177 Tann Sarayında Namaz indirimleri 180 Kur'an'daki "Çelişki"lerden I 183 Kur'an'daki "Çelişkilerden" II 186 Kur'an'daki "Akıl ve Bilim" Dışılıklar I 190 Kur'an'daki "Akıl ve Bilim" Dışılıklar II 193 Kur'an'daki "Akıl ve Bilim" Dışılıklar III 196 Kur'an'daki "Akıl ve Bilim" Dışılıklar IV 199 Kur'an'daki "Akıl ve Bilim" Dışılıklar V 202 Kur'an'daki "Akıl ve Bilim" Dışılıklar VI 205 Kur'an'daki "Akıl ve Bilim" Dışüıklar Vü 208 Kur'an'daki "Akıl ve Bilim" Dışılıklar VIII . -

The Discourse on the Praxis and Pragmatics of the Qur'an

TranscUlturAl, vol. 12.1 (2020), 75-98 . http://ejournals.library.ualberta.ca/index.php/TC The Discourse on the Praxis and Pragmatics of the Qur’an Retranslations in Turkish Sema Üstün Külünk 1. Introduction The Qur’an, holy book of all the Muslims around the world, has been partially and wholly translated into numerous languages since its revelation in Arabic in the 7th century (Binark and Eren. As a country, where the majority of the population identifies as Muslim, Turkey has hosted a great number of retranslations of the Qur’an into Turkish since the early Republican era as well. More than five-hundred Turkish retranslations of the Qur’an have become available since 1923 till the present day (Üstün 297). This number includes various re-editions of the same Qur’an translations, annotated formats, simplified versions, and facsimiles. As one of the most retranslated works in Turkish, Qur’an translations in Turkey constitute an intriguing site of research. Ongoing interest in these retranslations derives from a number of issues, including the sacred status of the source text, arguments over its untranslatability, the claimed deficiency of the human translator to render the words of the Holy creator, particular Arabicity of the source text vis-à-vis Turkish, and the hegemonic expertise claimed by faculties of theology vis-à-vis Translation Studies departments, creating a meta-narrative on the retranslations of the Qur’an in Turkish. As is well-known “retranslation” prevailingly serves as an equivocal frame of reference as “the act of translating a work that has previously been translated into the same language” and “the result of such an act, i.e. -

20 Years of Struggle for Freedom to Publish In

20 YEARS OF STRUGGLE FOR FREEDOM TO PUBLISH IN TURKEY 1994- 2014 20 YEARS OF STRUGGLE 20 YEARS OF STRUGGLE FOR FREEDOM TO PUBLISH IN TURKEY Freedom of Thought and Expression Awards and Freedom to Publish Reports FOR FREEDOM TO PUBLISH 1994 - 2014 IN TURKEY 1. EDITION İSTANBUL, SEPTEMBER 2014 ISBN 978-975-365-017-5 Freedom of Thought and Expression Awards All rights reserved. @TURKIYE YAYINCILAR VE YAYIN DAGITIMCILARI BIRLIGI DERNEGI and Freedom to Publish Reports Inonu Caddesi Opera Palas Apt. No: 55 D:2 34437 Gumussuyu, Beyoglu / ISTANBUL 1994 - 2014 T: 0 212 512 56 02 F: 0 212 511 77 94 E: [email protected] TRANSLATION Ali Ottoman, Funda Soysal, Deniz İnal EDITING Yonca Cingöz PROOF READING Sara Whyatt GRAPHIC DESIGN Elif Rifat TYPESETTING Nevruz Kıran Öksüz PRINTED AND BOUND IN Umut Matbaası 3 CONTENTS Foreword.........................................................................................................................................5 FOREWORD Freedom to Publish Report 1994.....................................................................................................8 Every year since 1995, the Turkish Publishers Association prepares Freedom Freedom of Thought and Expression Awards 1995........................................................................16 to Publish Report and hands out an award to a writer, a publisher and a booksell- er. This year the writer’s award goes to Tonguç Ok, an exceptionally productive Freedom of Thought and Expression Awards 1996........................................................................18 -

MEZHEPLER TARİHİ AKADEMİK YAYINLAR BİBLİYOGRAFYASI* Ahmet İshak DEMİR** Gülsüm KABA***

e-makâlât Mezhep Araştırmaları, IV/2 (Güz 2011), ss. 185-254. ISSN 1309-5803 | www.emakalat.com MEZHEPLER TARİHİ AKADEMİK YAYINLAR BİBLİYOGRAFYASI* Ahmet İshak DEMİR** Gülsüm KABA*** GİRİŞ Bilimsel çalışmalarda meydana gelen artış, bu çalışmalardan ha- berdar olma ve bunlara ulaşma güçlüğünü de beraberinde getirmiş- tir. Böyle olunca bütün bilim dallarıyla ilgili bibliyografik çalışmala- rın yapılması zorunluluğu belirmekte ve zaman zaman bu ihtiyacı gidermeye yönelik çeşitli çabalar ortaya konulmaktadır. Bu çalışmada Türkiye’de İslam Mezhepleri alanında yapılan kitap ve tez bazlı bilimsel çalışmaların, ulaşılabildiği kadarıyla bir bibli- yografyası oluşturulmaya gayret edilmiştir. Eser seçiminde konu ve nitelik kapsamı esnek tutularak itikâdî mezhepler ile dolaylı ilgili olanlar da bibliyografyamıza dahil edilmiştir. Böylece alan dâhilin- deki konuların neler olabileceği, ne kadar çalışma bulunduğu ve bu alanda hangi akademisyen ve yazarın ne tür çalışmalar ortaya koy- duğu ortaya çıkarılmaya çalışılmıştır. Dolaylı olarak da mezhepler tarihi alanında merak edilip üzerinde çalışılan konular bir araya gelmiş olmaktadır. Konuyla ilgili makale ve bildiriler ayrı bir çalışma olarak düşünüldüğünden kapsam dışı bırakılmıştır. Çalışmaların bir arada görülebilmesi için tezler ve kitaplar yazar soyadına göre alfabetik olarak verilmiştir. Tezlerin türü YL, DR, DOÇ, ve ÖÜ (öğretim üyeliği) kısaltmaları ile kitap çalışmalarından ayırt edilmiştir. _____ * Bu çalışma Rize Ü. Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü’ne bağlı olarak yapılmış yüksek lisans dönemi seminer çalışmasının gözden geçirilip geliştirilmiş halidir. ** Yrd. Doç. Dr. Rize Ün. İlahiyat Fak. [email protected] *** Rize Ü. SBE. İslam Mezhepleri Tarihi yüksek lisans öğrencisi 186 Mezhepler Tarihi Bibliyografyası Toplam 963 eserin yer aldığı çalışmamızda 455’i yüksek lisans, 169’u doktora ve 6 tanesi doçentlik, 1 tanesi de öğretim üyeliği tezi olmak üzere 624 adet tez ile 245 telif ve 81 çeviri olmak üzere 339 adet kitap listelenmiştir. -

Department of Economics Yale University P.O

DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS YALE UNIVERSITY P.O. Box 208268 New Haven, CT 06520-8268 http://www.econ.yale.edu/ Economics Department Working Paper No. 60 CHOICE UNDER PRESSURE A Dual Preference Model and Its Application Tolga Koker March 2009 This paper can be downloaded without charge from the Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1368398 Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1368398 CHOICE UNDER PRESSURE A Dual Preference Model and Its Application Tolga Koker* Yale University March 2009 Abstract By making a distinction between public and private preferences, the paper presents a dual preference model depicting possible responses (i.e., exit, sincere voice and self-subversion) to social pressures from two opposing pressure groups. Exit is deserting the setting; sincere voice is publicly expressing dissatisfaction and self-subversion is the misrepresentation of one’s private preference under social pressures. Exit and sincere voice involve prohibitive costs, making self-subversion the superior option. Massive self-subversion polarizes the society, harboring multiple social equilibria with oscillating public opinion. In an effort to dominate the public discourse, each rival pressure group opts for favorable corner equilibrium. The paper applies the dual preference model to Turkey where two kinds of self- subversion appear in response to competing Islamist and secularist social projects. Islamist pressures lead to pro-Islamist self-subversion, and secularist pressures to pro-secularist self-subversion, resulting in the polarization of the Turkish public opinion along Islamists vs. Secularists. Three field experiments with 450 respondents provide empirical support for the model’s conclusions. The paper ends with the discussion of the model’s implications for new social equilibrium(s). -

İndir PDF İndir

e-ISSN 2651-379X İBN HALDUN ÇALIŞMALARI DERGİSİ JOURNAL OF IBN HALDUN STUDIES | Cilt / Volume 1| Sayı / Issue 2 | Temmuz / July 2016 | Açık Erişim Dergi / Open Access Journal | Yayıncı İbn Haldun Üniversitesi / Publisher Ibn Haldun University | e-ISSN 2651-379X | Sıklık Yılda İki Sayı / Frequency bi-annually | İbn Haldun Üniversitesi Adına Sahibi Recep Şentürk, İbn Haldun Üniversitesi, Türkiye Yayın Kurulu Başkanı Recep Şentürk, İbn Haldun Üniversitesi, Türkiye Editörler Sönmez Çelik, İbn Haldun Üniversitesi, Türkiye Vahdettin Işık, İbn Haldun Üniversitesi, Türkiye Savaş Cihangir Tali, İbn Haldun Üniversitesi, Türkiye Editörler Kurulu Recep Şentürk, İbn Haldun Üniversitesi, Türkiye Sefa Bulut, İbn Haldun Üniversitesi, Türkiye Ali Osman Kuşakçı, İbn Haldun Üniversitesi, Türkiye Vahdettin Işık, İbn Haldun Üniversitesi, Türkiye Sönmez Çelik, İbn Haldun Üniversitesi, Türkiye Ahu Dereli Dursun, İstanbul Ticaret Üniversitesi, Türkiye Mehmet Öncel, İbn Haldun Üniversitesi, Türkiye Savaş Cihangir Tali, İbn Haldun Üniversitesi, Türkiye Danışma Kurulu Prof. Dr. Bruce B. Lawrence, Duke Universiry, ABD Prof. Dr. Tahsin Görgün, İstanbul 29 Mayıs Üniversitesi, Türkiye Prof. Dr. Miriam Cooke, Duke University, ABD Prof. Dr. Syed Farid Alatas, National University of Singapore, Singapur Dr. Hüseyin Yılmaz, George Mason University, ABD Yazı İşleri Müdürü Sönmez Çelik, İbn Haldun Üniversitesi, Türkiye İbn Haldun Çalışmaları Dergisi (e-ISSN 2651-379X), İbn Haldun Üniversitesi tarafından yılda iki kez yayınlanan hakemli bir dergidir. 2016 yılında yayımlanmaya başlanan dergi; dil, edebiyat, tarih, sanat, mimari, sosyoloji, ilahiyat ile insan ve toplum bilimleri alanlarında özgün bilimsel Türkçe, İngilizce ve Arapça makaleler yayımlar. Yazılarda belirtilen düşünce ve görüşlerden yazar(lar)ı sorumludur. Journal of Ibn Haldun Studies (e-ISSN 2651-379X) is published by Ibn Haldun University, which is a referred bi-annual and blind peer- review. -

Ali'siz Alevilik

Ali’siz Alevilik Faik Bulut Lisans eğitimini İstanbul Üniversitesi Tarih Bölümün1950 Kars doğumIu; İlkokulu köyünde ve Ortaokulu Kağızman'da Gazi Eğitim Enstitüsü mezunu. '68 Kuşağı'ndan olup, o dönem gençl ik hareketi içinde yer aldı. Siyasi nedenlerle. 1972-1980 arasında Suriye, Filistin, Lübnan ve İsrail'de bulundu. Bu süre içinde Arapça, İngilizce, Fransızca ve İbranice öğrendi. Ortadoğu, Arap-İslam dünyası üzerine incelemeler yaptı. 1980 yılında Türkiye'ye döndü. Gazetecilik mesleğine başladı. Büyük basın dahil çeşitli yayın organlarında Ortadoğu, Kürt ve İslam konularında muhabir ve köşe yazarı olarak çalıştı. Uzmanlık alanını genişleterek çalışmalarını kitaplaştırdı. Anadili Kürtçe dışında Türkçe, Arapça, İngilizce, Fransızca, İbranice ve Farsça biliyor. Gazetecilik mesleğini sürdürüyor. Şimdiye kadar şu eserleri yayınlandı: Filistin Rüyası (anı-belgesel), Filistin İntifada Dersleri, Allah Devletinde Demokrasi (1993 Turan Dursun Araştırma Ödülü), Devletin Gözüyle Kürt İsyanları (araştırma), Türk Basınında Kürtler (belgesel), Kürt Dilinin Tarihçesi (araştırma), İslamcı Örgütler (araştırma), Ordu ve Din (araştırma), İslam Komüncüleri (araştırma), Şeriat Gölgesinde Cezayir (araştırma), Ehmede Xane'nin Kaleminden Kürtlerin Bilinmeyen Dünyası (1995 Musa Anter Araştırma Ödülü’nde ikincilik), Dar Üçgende Üç İsyan: Kürdistan'da Etnik' Çatışmalar, Ali’siz Alevilik, İslam’da Cinsel Büyüler (araştırma), Horasan Kimin Yurdu? (araştırma), Horasan'dan Anadolu’ya Alevilik (araştırma), Eşitlikçi Dervişan Cumhuriyeti (araştırma). ARKA KAPAK AIi'siz Alevilik; Türkiye'de aydınlanma ile Şeriatçılık arasındaki fikirsel ve ideolojik mücadelede turnusol kağıdıdır, köşe taşıdır. Aleviliğin ilk kaynaklarını, tarihsel köklerini, dış etkilerini, Arap-İslam, Türk-İslam, İran-İslam dünyasındaki oluşum ve gelişimini irdeliyor. Alevi fikriyatının “Türklük veya Kürtlük”le özdeşleştirilmesini eleştiriyor. Aleviliği, Türk-İslam sentezi çerçevesinde Sünnileştirmeye çalışan görüşleri teşhir ediyor. Aleviliğin "İslam dışı" bir inanç, kültür ve yaşam tarzı olduğunu savunuyor. -

Martin Van Bruinessen

Martin van Bruinessen Martin van Bruinessen, "The Kurds and Islam". Working Paper no. 13, Islamic Area Studies Project, Tokyo, Japan, 1999. [this is a slightly revised version of the article in Islam des Kurdes (Les Annales de l'Autre Islam, No.5). Paris: INALCO, 1998, pp. 13- 35] The Kurds and Islam Martin van Bruinessen After Turkish, Arabic and Persian, Kurdish is the fourth language of the Middle East in number of speakers.[1] Presently the Kurds number, by conservative estimate, 20 to 25 million, which makes them the largest stateless people of the Middle East. Numerous Kurds have played important roles in the history of Islam but this has often remained unnoticed because they did not explicitly identify themselves by their ethnic origins; when they expressed themselves in writing they usually did so in one (or more) of the three neighbour languages. Kurdistan, the mountainous region where most of the Kurds lived, has long been a buffer zone between the Turkish-, Arabic- and Persian-speaking regions of the Muslim world. Politically, Kurdistan constituted a periphery to each of these cultural- political regions, but it has also had the important cultural role of mediation between them. Learned Kurds have frequently acted as a bridge between different intellectual traditions in the Muslim world, and Kurdish `ulama have made major contributions to Islamic scholarship and Muslim literature in Arabic and Turkish as well as Persian. Islam has, conversely, deeply affected Kurdish society; even ostensibly non-religious aspects of social and political life are moulded by it. As in other tribal societies, networks of madrasas and sufi orders have functioned as mechanisms of social integration, overcoming segmentary division. -

![Søren Dosenrode [Ed.]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4920/s%C3%B8ren-dosenrode-ed-5184920.webp)

Søren Dosenrode [Ed.]

Søren Dosenrode [Ed.] Freedom of the Press On Censorship, Self-censorship, and Press Ethics Nomos Søren Dosenrode [Ed.] Freedom of the Press On Censorship, Self-censorship, and Press Ethics Nomos © Foto Cover: istockphoto.com Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de. ISBN 978-3-8329-5184-9 1. Auflage 2010 © Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden 2010. Printed in Germany. Alle Rechte, auch die des Nachdrucks von Auszügen, der fotomechanischen Wiedergabe und der Übersetzung, vorbehalten. Gedruckt auf alterungsbeständigem Papier. This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically those of translation, reprinting, re-use of illustrations, broadcasting, reproduction by photocopying machine or similar means, and storage in data banks. Under § 54 of the German Copyright Law where copies are made for other than private use a fee is payable to »Verwertungsgesellschaft Wort«, Munich. Table of Contents Preface ............................................................................................ 7 Søren Dosenrode Section One Kaj Munk Chapter One: Approaching the Questions of Freedom of the Press, Censorship, Self-Censorship, and Press Ethics .................................... -

Current Trends in ISLAMIST IDEOLOGY

CT 25 repaginate.qxp_Layout 1 2020-01-30 5:23 PM Page 1 Current Trends IN ISLAMIST IDEOLOGY VOLUME 25 February, 2020 ■ WHERE WILL ERDOGAN’S REVOLUTION STOP? Suleyman Ozeren, Suat Cubukcu, and Matthew Bastug ■ THE SYRIA EFFECT: AL-QAEDA FRACTURES Charles Lister ■ THE ORIGINS OF BOKO HARAM—AND WHY IT MATTERS Bulama Bukarti ■ EDUCATOR OF THE FAITHFUL: THE POWER OF MOROCCAN ISLAM Bradley Davis ■ THE CO-OPTATION OF ISLAM IN RUSSIA Rebecca Fradkin ■ DEPLOYING SOCIAL MEDIA TO EMPOWER IRANIAN WOMEN: AN INTERVIEW WITH MASIH ALINEJAD Lela Gilbert Hudson Institute Center on Islam, Democracy, and the Future of the Muslim World CT 25 repaginate.qxp_Layout 1 2020-01-30 5:23 PM Page 2 CT 25 repaginate.qxp_Layout 1 2020-01-30 5:23 PM Page 3 CT 25 repaginate.qxp_Layout 1 2020-01-30 5:23 PM Page 4 CT 25 repaginate.qxp_Layout 1 2020-01-30 5:23 PM Page 1 Current Trends IN ISLAMIST IDEOLOGY VOLUME 25 Edited by Hillel Fradkin, Husain Haqqani, and Eric Brown Hudson Institute Center on Islam, Democracy, and the Future of the Muslim World CT 25 repaginate.qxp_Layout 1 2020-01-30 5:23 PM Page 2 ©2020 Hudson Institute, Inc. All rights reserved. ISSN: 1940-834X For more information about obtaining additional copies of this or other Hudson Institute publica- tions, please visit Hudson’s website at www.hudson.org/bookstore or call toll free: 1-888-554-1325. ABOUT HUDSON INSTITUTE Hudson Institute is a nonpartisan, independent policy research organization dedicated to innova- tive research and analysis that promotes global security, prosperity, and freedom.