Martin Van Bruinessen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/26/2021 08:13:54AM Via Free Access Matrimonial Alliances and the Transmission of Dynastic Power 223

EURASIAN Studies 15 (2017) 222-249 brill.com/eurs Matrimonial Alliances and the Transmission of Dynastic Power in Kurdistan: The Case of the Diyādīnids of Bidlīs in the Fifteenth to Seventeenth Centuries Sacha Alsancakli Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3 / UMR 7528 Mondes iranien et indien [email protected] Abstract The Diyādīnids of Bidlīs, one of the important Kurdish principalities of the early mod- ern period (fourteenth to seventeenth centuries), have constantly claimed a central role in the political powers of Kurdistan. This article will explore the ways in which the Diyādīnid’s matrimonial alliances helped bolster that claim and otherwise secure and enhance the political standing of the dynasty. * An earlier version of this paper was presented at the DYNTRAN panel “Familles, autorité et savoir dans l’espace moyen-oriental (XVe-XVIIe siècles)” of the 2nd Congress of the GIS “Moyen-Orient et mondes musulmans” (Paris, 5-8 July 2017). The French-German collective project DYNTRAN (Dynamics of Transmission: Families, Authority and Knowledge in the Early Modern Middle East [15th-17th centuries]) is cofounded by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR) and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) (ANR-14-FRAL-0009-01). All translations are my own unless stated otherwise. I have chosen to use a mixed translit- eration system in this article: Persian and Kurdish proper names are transliterated accord- ing to the system of the German Oriental Society (DMG, 1969) for Persian, except for the vocalization of the names of some Kurdish tribes and places, where forms closer to Kurdish prononciation have been preferred (eg. Boḫtān, not Buḫtān, Ḥazzō, not Ḥazzū). -

September 2013 KURDISTAN REGION of IRAQ

An eye on alluring leaders, emerging sectors, leading companies and rising trends shaping the future of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. THE REVIEW September 2013 KURDISTAN REGION OF IRAQ Exclusive Nechirvan Barzani Prime Minister Nechirvan Barzani on political stability, major structural reforms, and economic growth EXCLUSIVE ANALYSIS Minister Yasin Sheikh by Dr. Fuad Hussein Abu Bakir Mawati INVEST IN GROUP AN EYE ON THE EMERGING WORLD Home to several major real estate and development projects, Empire World spans a land area of 750,000 m2. Empire’s multi-faceted and mixed-use approach to land utilization affords the Project the distinguishing characteristic of a city within a city. CONTENTS SEPTEMBER 2013 Diplomacy & Politics 22 Shaping the Future of the Kurdistan Region — PM Nechirvan Barzani 26 Diplomacy in Action — Dr. Fuad Hussein 28 Planned Expansion — Nawzad Hadi 30 Reaffirming the UK’s long-term commitment — Hugh Evans 33 Importing Experience — Jeroen Kelderhuis “The Kurdistan Region is a suc- “I believe that in 3-5 years, cess story, not only in comparison Erbil will continue to to the rest of the country but to the expand, with significant rest of the region as well.” growth in all sectors.” Page 26 Page 28 Economy “We want to demon- strate that the private 36 Strong, Inspiring, Visionary — Hawre Daro Noori 40 Invest in Slemani — Farman Gharib Sa’eed sector is capable of 42 Changing the Mindset — Jamal Asfour raising the standard 44 Huge Opportunities — Serwan M. Mahmood of an industry and 46 Staffing Kurdistan— Haller Dleir Miran provide a model for 48 An eye on Integrity, Political & Security Risks — Harry Bucknall others to follow.” Page 36 Energy 52 Preparing to Export — Yasin Sheikh Abu Bakir Muhammad Mawati 54 Electricity Factsheet 56 Commitment to Clean Energy — Shakir Wajid Shakir 58 Developing to be a Major — Umur Eminkahyagil 60 High-Level of Expertise — Dr. -

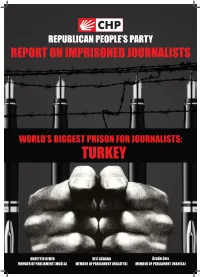

Report on Imprisoned Journalists

REPUBLICAN PEOPLE’S PARTY REPORT ON IMPRISONED JOURNALISTS WORLD’S BIGGEST PRISON FOR JOURNALISTS: TURKEY NURETTİN DEMİR VELİ AĞBABA ÖZGÜR ÖZEL MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT (MUĞLA) MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT (MALATYA) MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT (MANİSA) REPUBLICAN PEOPLE’S PARTY PRISON EXAMINATION AND WATCH COMMISSION REPORT ON IMPRISONED JOURNALISTS WORLD’S BIGGEST PRISON FOR JOURNALISTS: TURKEY NURETTİN DEMİR VELİ AĞBABA ÖZGÜR ÖZEL MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT (MUĞLA) (MALATYA) (MANİSA) CONTENTS PREFACE, Ercan İPEKÇİ, General Chairman of the Union of Journalists in Turkey ....... 3 1. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................... 11 2. JOURNALISTS IN PRISON: OBSERVATIONS AND FINDINGS .................. 17 3. JOURNALISTS IN PRISON .......................................................................... 21 3.1 Journalists Put on Trial on Charges of Committing an Off ence against the State and Currently Imprisoned ................................................................................ 21 3.1.1Information on a Number of Arrested/Sentenced Journalists and Findings on the Reasons for their Arrest ........................................................................ 21 3.2 Journalists Put on Trial in Association with KCK (Union of Kurdistan Communities) and Currently Imprisoned .................................... 32 3.2.1Information on a Number of Arrested/Sentenced Journalists and Findings on the Reasons for their Arrest ....................................................................... -

Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nineteenth-Century Iran

publications on the near east publications on the near east Poetry’s Voice, Society’s Song: Ottoman Lyric The Transformation of Islamic Art during Poetry by Walter G. Andrews the Sunni Revival by Yasser Tabbaa The Remaking of Istanbul: Portrait of an Shiraz in the Age of Hafez: The Glory of Ottoman City in the Nineteenth Century a Medieval Persian City by John Limbert by Zeynep Çelik The Martyrs of Karbala: Shi‘i Symbols The Tragedy of Sohráb and Rostám from and Rituals in Modern Iran the Persian National Epic, the Shahname by Kamran Scot Aghaie of Abol-Qasem Ferdowsi, translated by Ottoman Lyric Poetry: An Anthology, Jerome W. Clinton Expanded Edition, edited and translated The Jews in Modern Egypt, 1914–1952 by Walter G. Andrews, Najaat Black, and by Gudrun Krämer Mehmet Kalpaklı Izmir and the Levantine World, 1550–1650 Party Building in the Modern Middle East: by Daniel Goffman The Origins of Competitive and Coercive Rule by Michele Penner Angrist Medieval Agriculture and Islamic Science: The Almanac of a Yemeni Sultan Everyday Life and Consumer Culture by Daniel Martin Varisco in Eighteenth-Century Damascus by James Grehan Rethinking Modernity and National Identity in Turkey, edited by Sibel Bozdog˘an and The City’s Pleasures: Istanbul in the Eigh- Res¸at Kasaba teenth Century by Shirine Hamadeh Slavery and Abolition in the Ottoman Middle Reading Orientalism: Said and the Unsaid East by Ehud R. Toledano by Daniel Martin Varisco Britons in the Ottoman Empire, 1642–1660 The Merchant Houses of Mocha: Trade by Daniel Goffman and Architecture in an Indian Ocean Port by Nancy Um Popular Preaching and Religious Authority in the Medieval Islamic Near East Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nine- by Jonathan P. -

M. Fethullah Gülen's Understanding of Sunnah

M. FETHULLAH GÜLEN’S UNDERSTANDING OF SUNNAH Submitted by Mustafa Erdil A thesis in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Theology Faculty of Theology and Philosophy Australian Catholic University Research Services Locked Bag 4115 Fitzroy, Victoria 3065 Australia 23 JULY 2016 1 | P a g e STATEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP AND SOURCES This thesis contains no material published elsewhere or extracted in whole or in part from a thesis by which I have qualified for or been awarded another degree or diploma. No other person’s work has been used without due acknowledgement in the main text of the thesis. This thesis has not been submitted for the award of any degree or diploma in any other tertiary institution. All research procedures in the thesis received the approval of the relevant Ethics/Safety Committees (where required). Mustafa Erdil 23 JULY 2016 Signature: ABSTRACT The aim and objective of this study is to highlight the importance of and the status of hadith in Islam, as well as its relevance and reference to sunnah, the Prophetic tradition and all that this integral source of reference holds in Islam. Furthermore, hadith, in its nature, origin and historical development with its close relationship with the concept of memorisation and later recollection came about after the time of Prophet Muhammad. This study will thus explore the reasons behind the prohibition, in its initial stage, with the authorisation of recording the hadiths and its writing at another time. The private pages of hadith recordings kept by the companions will be sourced and explored as to how these pages served as prototypes for hadith compilations of later generations. -

Islamism and Totalitarianism Jeffrey M

This article was downloaded by: [Bale, Jeffrey M.] On: 17 December 2009 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 917909397] Publisher Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37- 41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713636813 Islamism and Totalitarianism Jeffrey M. Bale a a Monterey Terrorism Research and Education Program and Graduate School of International Policy Studies, Monterey Institute of International Studies, USA Online publication date: 17 December 2009 To cite this Article Bale, Jeffrey M.(2009) 'Islamism and Totalitarianism', Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions, 10: 2, 73 — 96 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/14690760903371313 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14690760903371313 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

E-Makâlât ISSN 1309-5803 Mezhep Araştırmaları Dergisi 10, Sy

e-makâlât www.emakalat.com ISSN 1309-5803 Mezhep Araştırmaları Dergisi 10, sy. 2 (Güz 2017): 435-454 Journal of Islamic Sects Research 10, no. 2 (Fall 2017): 435-454 Hakemli Araştırma Makalesi | Peer-reviewed Research Article BİR ETNO-DİNİ İNANIŞ OLARAK İRAN’DAKİ YARSAN İNANCI: TARİHİ, ESASLARI VE BUGÜNKÜ DURUMU Ethno-Religious Beliefs in Iran: History, Principles and Current State of Yarsan Faith İsmail Numan TELCİ* Öz Abstract İran’da kökleri yüzlerce yıl öncesine Yarsan faith is one of the most indigenous dayanan dini gruplardan birisi olan religious groups in Iran that has a long his- Yarsan inanışı günümüzde Tahran tory in the country’s socio-religious lands- rejiminin uyguladığı insan hakları cape. Its believers claim that the Iranian ihlalleri nedeniyle hem bölgesel hem government practices assimilation-driven de uluslararası araştırmacıların dik- policies towards them, but the members of katini çekmektedir. 12 İmam Şiili- Yarsan community have been confronting such policies by clinging to their identity. ğini benimseyen İran yönetiminin As a result of these discriminatory policies, kendilerine yönelik asimilasyon poli- thousands of Yarsan believers have emig- tikası izlediğini iddia eden Yarsan rated to Western Europe for seeking asy- inananları, Tahran rejimine karşı lum and refugee status. In recent years, lo- zaman zaman protesto gösterileri cal, regional and international scholars and düzenlemektedir. Son yıllarda bin- institutions have started to recognize hu- lerce üyesi özellikle Avrupa ülkele- man rights violations towards the Yarsan rine iltica eden Yarsan inanışıyla il- faith by the Iranian regime. Despite the re- gili literatürde kısıtlı bir yazın bu- porting of local and international human lunmaktadır. -

Illiberal Media and Popular Constitution-Making in Turkey

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Communication Department Faculty Publication Series Communication 2020 Illiberal Media and Popular Constitution-Making in Turkey Burcu Baykurt Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/communication_faculty_pubs 1 Illiberal Media and Popular Constitution Making in Turkey 1. Introduction Popular constitution making, a process that allows for public participation as opposed to a handful of elites writing a fundamental social contract behind closed doors and imposing it on the rest of society, is tricky. It sounds like a noble idea in theory, but it is difficult to execute effectively, efficiently, and, most importantly, democratically. Even trickier are the roles of publicity and media in popular constitution making. What are the consequences of reporting during the drafting of a new constitution? In what ways could the media lend legitimacy to the process by informing the public and incorporating public opinion into the drafting of a constitution? Coupled with the rise of new media technologies, an ideal of participatory constitution making (and an active role for the media) may seem desirable, not to mention attainable, but there are myriad ways to participate, and basing a constitution on popular opinion could easily devolve into a majority of 50 percent plus one that imposes its will on the rest. The bare minimum, ideally, is to expect journalists to report on facts without bowing to political or economic pressures, but even that is easier said than done. For which audiences are these journalistic facts intended? For those leaders drafting the new constitution or the public at large? These are not easy questions to answer empirically, not only because media and communications are often neglected in studies of constitution making, but also because the relationship between the two is hard to ascertain precisely. -

Individual Values and Acculturation Processes of Immigrant Groups from Turkey: Belgium, Germany, and the Netherlands

Journal of Identity and Migration Studies Volume 15, number 1, 2021 RESEARCH ARTICLES Individual Values and Acculturation Processes of Immigrant Groups from Turkey: Belgium, Germany, and the Netherlands Ergün ÖZGÜR Abstract. This quantitative research describes the values of three ethnic groups in comparison with each other as well as with the native groups. It also discusses the acculturation processes of Circassians, Kurds and Turks in Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands. The first research question, “Do immigrant and native groups have similar values?” shows value similarities of Circassians with the French in Belgium, German and Dutch respondents. They have value differences from Flemish respondents. Kurds and Turks have value similarities with German and Flemish respondents, and they have value differences from the Dutch. The second research question, “What acculturation processes do immigrant groups go through?”, confirms high hard assimilation means of Circassians, and high separation means of Turks and Kurds in the Netherlands. In Belgium, Turks have hard high assimilation means, is unexpected, given that Belgium has been a modestly multicultural country. In Turkey, Kurds and Circassians have high assimilation, and Circassians have high integration means. Contrary to the discourses about less participation of immigrants, research findings reveal value similarities of immigrant and native groups in three countries. The European authorities need to develop participative policies to reduce immigrants’ sense of discrimination and natives’ perception of threat for a peaceful society. Keywords: immigrant groups from Turkey, individual values, acculturation processes, discrimination-threat perception, European countries Introduction This comparative research describes the values of three ethnic groups in comparison with each other as well as with the native groups. -

Iraq and the Kurds: the Brewing Battle Over Kirkuk

IRAQ AND THE KURDS: THE BREWING BATTLE OVER KIRKUK Middle East Report N°56 – 18 July 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. COMPETING CLAIMS AND POSITIONS................................................................ 2 A. THE KURDISH NARRATIVE....................................................................................................3 B. THE TURKOMAN NARRATIVE................................................................................................4 C. THE ARAB NARRATIVE .........................................................................................................5 D. THE CHRISTIAN NARRATIVE .................................................................................................6 III. IRAQ’S POLITICAL TRANSITION AND KIRKUK ............................................... 7 A. USES OF THE KURDS’ NEW POWER .......................................................................................7 B. THE PACE OF “NORMALISATION”........................................................................................11 IV. OPPORTUNITIES AND CONSTRAINTS................................................................ 16 A. THE KURDS.........................................................................................................................16 B. THE TURKOMANS ...............................................................................................................19 -

2Artboard 1 Copy

The First One Who Divided Their Countries and Displaced Them Suleiman the Magnificent Inaugurated the Kurdish “Bloodbath” History is merciless. Leaders and headmen shall be aware that one mistake may lead a nation to damage. Sometimes, it may rather eliminate it. This is what happened to Kurds and their relationship with the Ottoman Empire. It started with mutual concern between the two parties. It was followed by an alliance that quickly ended and turned into hostility that caused bloody massacres from which Kurds suffered until today. The story details date back to (1514 AD) when Idris Bitlisi, the leader of Kurds at that time, made a political deal with Selim I (1520 -1512). The deal was that Kurds should help Selim to gain victory over the Safavid state; in return, Ottoman Sultan shall recognize the autonomy of Kurds and give them freedom to form their own army and in addition; not to interfere in their internal affairs. Indeed, the deal was made and Selim I gained victory over Safavids in Chaldiran (1514 AD). The deal between Kurds and Turkish was named Chaldiran. The situation did not last long; as soon as Selim I died (1520 AD), everything changed. Although alliances made between countries do not depend on the life or death of people, this was not applicable to Turkish sultans as whenever one of them superseded, he breached the covenant of his predecessor and so on. Thus, they were known as the Empire of breaching covenants. This was the first mistake of Kurds, even if they realized it too late. -

I TURKEY and the RESCUE of JEWS DURING the NAZI ERA: a RE-APPRAISAL of TWO CASES; GERMAN-JEWISH SCIENTISTS in TURKEY & TURKISH JEWS in OCCUPIED FRANCE

TURKEY AND THE RESCUE OF JEWS DURING THE NAZI ERA: A REAPPRAISAL OF TWO CASES; GERMAN-JEWISH SCIENTISTS IN TURKEY & TURKISH JEWS IN OCCUPIED FRANCE by I. Izzet Bahar B.Sc. in Electrical Engineering, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, 1974 M.Sc. in Electrical Engineering, Bosphorus University, Istanbul, 1977 M.A. in Religious Studies, University of Pittsburgh, 2006 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Art and Sciences in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Cooperative Program in Religion University of Pittsburgh 2012 i UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences This dissertation was presented by I. Izzet Bahar It was defended on March 26, 2012 And approved by Clark Chilson, PhD, Assistant Professor, Religious Studies Seymour Drescher, PhD, University Professor, History Pınar Emiralioglu, PhD, Assistant Professor, History Alexander Orbach, PhD, Associate Professor, Religious Studies Adam Shear, PhD, Associate Professor, Religious Studies Dissertation Advisor: Adam Shear, PhD, Associate Professor, Religious Studies ii Copyright © by I. Izzet Bahar 2012 iii TURKEY AND THE RESCUE OF JEWS DURING THE NAZI ERA: A RE-APPRAISAL OF TWO CASES; GERMAN-JEWISH SCIENTISTS IN TURKEY & TURKISH JEWS IN OCCUPIED FRANCE I. Izzet Bahar, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2012 This study aims to investigate in depth two incidents that have been widely presented in literature as examples of the humanitarian and compassionate Turkish Republic lending her helping hand to Jewish people who had fallen into difficult, even life threatening, conditions under the racist policies of the Nazi German regime. The first incident involved recruiting more than one hundred Jewish scientists and skilled technical personnel from German-controlled Europe for the purpose of reforming outdated academia in Turkey.