Ghost Stories, Dir. by Andy Nyman, Jeremy Dyson (Lionsgate Films, 2018)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entertainment

ENTERTAINMENT All The Park’s A Stage Sit underneath the stars and experience the magic of open-air theatre in the beautiful setting of Regent’s Park. Jo Caird goes behind the curtains for the classic-packed season ahead. here are few London experiences only began to take shape in 1953 and form of The Gershwins’ Porgy And Bess more magical than watching the it wasn’t until 1976 that the current (17 Jul-23 Aug) and To Kill A Mockingbird T night fall over the Open Air Theatre amphitheatre-style auditorium was built. (28 Aug-13 Sep). The latter show, based in Regent’s Park. When the performance All My Sons, which kicks off the season, on the iconic novel of the same name by begins, the outdoor theatre and is directed by the venue’s artistic director, Harper Lee, returns to Regent’s Park picturesque glade that surrounds it are Timothy Sheader, whose 2010 Open Air following last year’s sell-out run. The theatre bathed in the soft light of early evening. Theatre production of Arthur Miller’s The also presents a show for family audiences: But then, imperceptibly, darkness Crucible was lauded by the critics and a re-imagining of Shakespeare’s Twelfth envelops the auditorium until there is earned him a best director gong from Night, with live music, for children aged six nothing to see but the drama being What’s On Stage. The play, which Miller and over (21 Jun-12 Jul). JENSEN DAVID © played out before you. The atmosphere wrote in 1947, is based on the true story As you sit in the Inner Circle of historic is suddenly, startlingly, intimate. -

The Limehouse Golem’ by

PRODUCTION NOTES Running Time: 108mins 1 THE CAST John Kildare ................................................................................................................................................ Bill Nighy Lizzie Cree .............................................................................................................................................. Olivia Cooke Dan Leno ............................................................................................................................................ Douglas Booth George Flood ......................................................................................................................................... Daniel Mays John Cree .................................................................................................................................................... Sam Reid Aveline Mortimer ............................................................................................................................. Maria Valverde Karl Marx ......................................................................................................................................... Henry Goodman Augustus Rowley ...................................................................................................................................... Paul Ritter George Gissing ................................................................................................................................ Morgan Watkins Inspector Roberts ............................................................................................................................... -

Theater in England Syllabus 2010

English 252: Theatre in England 2010-2011 * [Optional events — seen by some] Monday December 27 *2:00 p.m. Sleeping Beauty. Dir. Fenton Gay. Sponsored by Robinsons. Cast: Brian Blessed (Star billing), Sophie Isaacs (Beauty), Jon Robyn (Prince), Tim Vine (Joker). Richmond Theatre *7:30 p.m. Mike Kenny. The Railway Children (2010). Dir. Damian Cruden. Music by Christopher Madin. Sound: Craig Veer. Lighting: Richard G. Jones. Design: Joanna Scotcher. Based on E. Nesbit’s popular novel of 1906, adapted by Mike Kenny. A York Theatre Royal Production, first performed in the York th National Railway Museum. [Staged to coincide with the 40 anniversary of the 1970 film of the same name, dir. Lionel Jefferies, starring Dinah Sheridan, Bernard Cribbins, and Jenny Agutter.] Cast: Caroline Harker (Mother), Marshall Lancaster (Mr Perks, railway porter), David Baron (Old Gentleman/ Policeman), Nicholas Bishop (Peter), Louisa Clein (Phyllis), Elizabeth Keates Mrs. Perks/Between Maid), Steven Kynman (Jim, the District Superintendent), Roger May (Father/Doctor/Rail man), Blair Plant(Mr. Szchepansky/Butler/ Policeman), Amanda Prior Mrs. Viney/Cook), Sarah Quintrell (Roberta), Grace Rowe (Walking Cover), Matt Rattle (Walking Cover). [The production transforms the platforms and disused railway track to tell the story of Bobby, Peter, and Phyllis, three children whose lives change dramatically when their father is mysteriously taken away. They move from London to a cottage in rural Yorkshire where they befriend the local railway porter and embark on a magical journey of discovery, friendship, and adventure. The show is given a touch of pizzazz with the use of a period stream train borrowed from the National Railway Museum and the Gentlemen’s saloon carriage from the famous film adaptation.] Waterloo Station Theatre (Eurostar Terminal) Tuesday December 28 *1:45 p.m. -

A Second Book of Essential Advice and Insight for Actors More Golden

Published by Nick Hern Books A second book of essential advice and insight for actors 9 More Golden Rules of Acting by Andy Nyman 201 Further priceless and witty nuggets of wisdom, from an experienced actor, writer and / director – full-colour illustrations throughout ISBN: 978 1 84842 874 4 09 £7.99 paperback 128pp Publication date: 3 October 2019 / Andy Nyman’s first book, The Golden Rules of Acting, has become a bestseller in the acting world. Now he returns to bring performers more priceless nuggets gleaned from more than thirty years in the acting business. 24 This book will help actors to... • Learn to love auditions and self-tapes (yes, really!) • Look after their mental health • Deal with success and failure • Burst a few bubbles that need bursting Written with the same candid wit as his first book, this is every actor's new best friend – in handy paperback form. Andy Nyman said: ‘I’ve been blown away with the response to The Golden Rules of Acting. The love it’s received - from newcomers to film stars - is truly overwhelming. More Golden Rules of Acting has been written in the same way as the first volume: noting and observing lessons I have learnt in the seven years since the first book came out. It addresses many new themes that have emerged in that time, such as self-taping and managing one’s mental health. I truly hope actors love it as much as they do the first book.’ Praise for More Golden Rules of Acting release ‘With great humour, wisdom and panache, Andy Nyman presents tasty advice for any actor. -

Lyric Hammersmith Press Release

PRESS RELEASE 04 September 2019 LYRIC HAMMERSMITH SPRING 2019 SEASON ANNOUNCEMENT Today the Lyric Hammersmith announces its Spring 2019 season, the final productions programmed by outgoing Artistic Director Sean Holmes. The season celebrates Holmes’ tenure - bringing back one of his most successful shows, reflecting the Lyric’s partnerships with the UK’s leading theatre companies, and embodying a reputation for daring new work alongside a commitment to nurturing the creativity of young people. Leave to Remain – the world premiere of a new play with songs by Matt Jones and Kele Okereke opens the season. Commissioned by the Lyric, directed by Robby Graham and designed by Rebecca Brower, with Olivier Award nominated actor Tyrone Huntley in the lead role. The first song from Leave to Remain, ‘Not the drugs talking’ written and performed by Bloc Party’s Kele Okereke is released today, available on iTunes and Spotify. The Lyric welcomes the highly acclaimed 1927 Theatre Company with The Animals and Children Took to the Streets and Kneehigh’s Dead Dog in a Suitcase (and other love songs). Ghost Stories – following worldwide success and the smash hit movie, the original terrifying hit is back. Written by Andy Nyman and Jeremy Dyson and directed by Andy Nyman, Jeremy Dyson and Sean Holmes. Continuing the theatre’s commitment to providing opportunities for young creative talent, Holly Race Roughan is announced as the Artistic Director for the Lyric Ensemble for 2019 and TD Moyo as the director for the lead show of the Evolution Festival. A new season of Little Lyric shows is announced for families and children under 11, presented in the newly refurbished studio theatre. -

Still Kicking Ass!

THE MAGIC MAGAZINE FOR MAGICIANS & MENTALISTS Taster Issue No.19 PAUL ZENON NICE AND SLEAZY DOES IT! HYPNOSIS YOU ARE FEELING DROWSY... (MAGICSEEN HAS THAT EFFECT ON READERS!) S.A.M.P.A ANDY DOES THE TRICK REVIEWS NYMAN 20 MAGIC HEADLINES WE’D LIKE TO SEE STILL KICKING ASS! BOOK TO CD PLAYER RABBIT IN HAT PUPPET - £295.00 - £24.99 At first there is an ordinary book in This is a lovely item, suitable for kids the magician’s hand. He shows it to and adults alike. You start off by the audience, so the spectators see holding a black top hat with both that is a regular book. Then he hands. As you look away, a rabbit opens the book and tears cuts out a page and draws a CD player pops his head out of the hat. As you on it. Then he places it in front of the book and then removing it. start to look back, it pops back in. Amazingly a CD player now takes the place of the book, which can A great comedy item that is loved by be shown on all sides to be solid. You can perform this item with children and adults alike with endless different methods to suit your own style. Size when open is possibilities. 40 x 27 x 24 cm Weight: 2 Kg PANDORA - £22.95 DOVE PAN REVERSE - This is one of the funniest and most startling ways NEW MODEL of producing a selected card that I have ever seen. In effect a card is selected and returned to - £85.00 the pack. -

1. UK Films for Sale TIFF 2016

Prepared by Although great efforts have been made to present correct and up-to-date details, no warranty is made regarding the accuracy or completeness of the information in this listing. Films have been included because they match several criteria, including: Where completed, films are less than one year old (not seen at or before AFM 2015). They are represented in person by a contactable sales company at AFM in 2016. 47 Meters Down TAltitude Film Sales Cast: Claire Holt, Mandy Moore , Matthew Modine Robin Andrews +44 796 842 8658 Genre: Thriller [email protected] Director: Johannes Roberts Market Office: Loews #863 Status: Completed Home Office tel: +44 20 7478 7612 Synopsis: Twenty-something sisters Kate and Lisa are gorgeous, fun-loving and ready for the holiday of a lifetime in Mexico. When the opportunity to go cage diving to view Great White sharks presents itself, thrill-seeking Kate jumps at the chance while Lisa takes some convincing. After some not so gentle persuading, Lisa finally agrees and the girls soon find themselves two hours off the coast of Huatulco and about to come face to face with nature's fiercest predator. But what should have been the trip to end all trips soon becomes a living nightmare when the shark cage breaks free from their boat, sinks and they find themselves trapped at the bottom of the ocean. With less than an hour of oxygen left in their tanks, they must somehow work out how to get back to the boat above them through 47 meters of shark-infested waters. -

WHAT the FEST!? Genre Film Festival Announces Full Lineup

Media Alert WHAT THE FEST!? Genre Film Festival Announces Full Lineup Festival Featuring a Devil’s Dozen of Eleven Unique Events, with Bizarro World Premieres, Cinematic Oddities and Unforgettable Moments of Onscreen Mayhem to Take Place March 29th - April 1st at New York’s IFC Center (New York, NY | March 7, 2018) IFC Center is proud to announce the full slate for the upcoming film festival What the Fest!? (www.whatthefestnyc.com), a four-day showcase of outrageous content -- horror, sci-fi, documentary, thrillers, and beyond -- from March 29th through April 1st. What the Fest!? will feature exciting premieres, including one world premiere, one US premiere, many New York premieres and the world premiere of a new digital restoration of a film never before released in the U.S. What the Fest!? also boasts under the radar cinematic finds, film festival hits from Sundance, TIFF, and Rotterdam, as well as buzzworthy talent in-person at screenings and post-screening events. Opening night of What the Fest!? will feature the New York Premiere of Coralie Fargeat’s REVENGE, a thriller about a mistress who exacts “revenge” on her married lover and his friends, turning their annual hunting trip into a decidedly deadlier adventure. The closing night film will be Jenn Wexler’s THE RANGER, about a group of teen punks on the lam, who hide out from the cops in a remote cabin… only to run into bigger troubles. Wexler will appear with the film, along with producer and co-star Larry Fessenden of Glass Eye Pix. “It's a thrill to celebrate the opening of the festival with a powerhouse film and filmmaker like Coralie Fargeat. -

Ghost Stories

1 / 2 Ghost Stories 4 days ago — Photo of the ruins of Gillespie Mansion taken in 1983. Courtesy of Deborah Moore Wolff. Every week, we explore a different Texas ghost story or .... New Orleans Ghost Stories · Coven: The (Un)True American Horror Story · The Truth About the Casket Girls · The Axeman of New Orleans · The Dark Side of Mardi .... Apr 20, 2018 — With a movie title like Ghost Stories, you'd expect a few decent frights. But this three-part British creepshow from writer-directors Andy Nyman .... Parcast Network's all-new original series is here—and with it, the scariest, most hair-raising ghost stories ever imagined. Join host Alastair Murden as he .... Jan 1, 2019 — You may think you're immune to scary ghost stories, but one of these truly terrifying tales may just make you afraid of the dark again.. I'm surprised how inappropriate, yet hilarious this is [Ghost Stories]. Clip. 00:00. 00:00. 11.3k. 6. 626 Share. 626 Comments sorted byBest. Log in or sign up to .... The Spookiest Ghost Stories From All 50 States. BY mentalfloss .com. October 8, 2018. iStock. From heartbroken brides to spectral oenophiles, America is a .... Dec 17, 2019 — Dickens was also a huge editor of Christmas ghost stories. He believed that “Christmas Eve [… is the] “witching time for Story-telling” and .... Nov 4, 2019 — These menacing tales are as old as culture, ghost stories whispered around crackling campfires and swapped on playgrounds. The details shift .... Dec 15, 2017 — Charles Dickens' A Christmas Carol was first published in 1843, and its story about a man tormented by a series of ghosts the night before .. -

GOTHIC: the DARK HEART of FILM Season Launches on 21 October at BFI SOUTHBANK, London

GOTHIC: THE DARK HEART OF FILM Season Launches on 21 October at BFI SOUTHBANK, London Part 1: MONSTROUS & Part 2: THE DARK ARTS Featuring special guests Roger Corman, Dario Argento and George A Romero Plus previews and events with Sir Christopher Frayling, Charlie Brooker, Charlie Higson, Russell Tovey, Anthony Head, Benjamin Zephaniah, Mark Gatiss, John Das, Philip Saville and Sarah Karloff The BFI blockbuster project GOTHIC: THE DARK HEART OF FILM launches at BFI Southbank on Monday 21 October and runs until Friday 31 January 2014. With the longest running season ever held to celebrate GOTHIC, one of Britain’s biggest cultural exports. An interview with the legendary director Roger Corman (The Masque of the Red Death, 1964) on 25 October will be followed with a haunting Hallowe’en that will fill BFI screens with mummies and vampires – old and new. Exclusive Film and TV previews will feature on-stage interviews with cinema luminaries such as George A Romero (Night of the Living Dead, 1968) and Dario Argento (Suspiria, 1976), and Sonic Cinema music nights such as the UK premiere of the Roland S Howard (The Birthday Party, Crime and the City Solution) documentary Autoluminescent (2011), accompanied by a live performance from Savages and HTRK. There will be specially curated exhibitions in the Atrium and Mezzanine that offer the chance to view the original contracts for Peter Cushing and Sir Christopher Lee at Hammer and Truman Capote’s handwritten screenplay for The Innocents (1961), plus Mediatheque programmes from the BFI National Archive, horribly good Family Fundays, education events and panel discussions, while across the length and breadth of the UK, GOTHIC will thrill audiences with fantastic screenings and restored films, starting with Werner Herzog’s Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979) on 31 October. -

Skylight by David Hare Skylight

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Skylight by David Hare Skylight. Kyra is a young teacher working and living in one of London's less attractive districts. Tom's wife has recently died of cancer: he is a wealthy entrepreneur and Kyra's former lover. On a cold winter night Tom's teenage son, Edward, calls on the young teacher to beg her to be reconciled with his father. Tom himself arrives, wishing to expiate his guilt and renew his lust. Kyra complies, sort of, until the debate soars and the insults fly in a way that makes you wish your own kitchen-table tiffs were half as brutal, half as civilised. David Hare's passionate play is sharp and satisfying, an impassioned head-on collision of values and confused desires. Author David Hare. Sir David Hare (b 1947) Hare was born in Bexhill, East Sussex into a family with no tradition in theatre but which was keen for him to better himself through education, with the goal of becoming a chartered accountant. He has written little of his family and childhood except to record that Bexhill in the Fifties was "incredibly dull". In 1970 his first play 'Slag' was performed at the Hampstead Theatre Club and a year later he first worked at the National Theatre, beginning one of the longest relationships of any playwright with a contemporary theatre. Through the 1970s he also ran a touring theatre company working with a number of other writers and then in 1978 wrote 'Plenty', his most ambitious play to date which was almost universally panned by the London critics. -

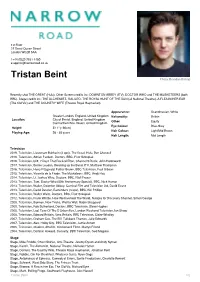

Tristan Beint Photo: Brandon Bishop

1st Floor 37 Great Queen Street London WC2B 5AA t +44 (0)20 7831 4450 e [email protected] Tristan Beint Photo: Brandon Bishop Recently shot THE GREAT (Hulu). Other Screen credits inc: DOWNTON ABBEY (ITV), DOCTOR WHO and THE MUSKETEERS (both BBC). Stage credits inc: THE ALCHEMIST, GALILEO, THE ROYAL HUNT OF THE SUN (all National Theatre), A FLEA IN HER EAR (The Old Vic) and THE COUNTRY WIFE (Theatre Royal Haymarket). Appearance: Scandinavian, White Greater London, England, United Kingdom Nationality: British Location: City of Bristol, England, United Kingdom Other: Equity Carmarthenshire, Wales, United Kingdom Eye Colour: Blue-Grey Height: 5'11" (180cm) Hair Colour: Light/Mid Brown Playing Age: 26 - 38 years Hair Length: Mid Length Television 2019, Television, Lieutenant Bukharin (2 eps), The Great, Hulu, Ben Chessell 2018, Television, Adrian Pardem, Doctors, BBC, Piotr Szkopiak 2018, Television, Cliff, 7 Days That Rocked Elton, Channel 5/Reelz, John Holdsworth 2017, Television, Bernie Leadon, Breaking up the Band, ITV, Matthew Thompson 2016, Television, Harry Fitzgerald, Father Brown, BBC Television, Paul Gibson 2015, Television, Vicomte de la Prade, The Musketeers, BBC, Andy Hay 2014, Television, Lt. Joshua Wise, Doctors, BBC, Niall Fraser 2013, Television, Tom, Doctor Who (50th Anniversary Special), BBC, Nick Hurran 2013, Television, Waiter, Downton Abbey, Carnival Film and Television Ltd, David Evans 2013, Television, David Dessler, Eastenders (3 eps), BBC, Nic Phillips 2013, Television, Walter Waite, Doctors, BBC, Piotr Szkopiak