Philippines: Human Rights Education in Nueva Ecija

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Historical Evaluation of the Emergence of Nueva Ecija As the Rice Granary of the Philippines

Presented at the DLSU Research Congress 2015 De La Salle University, Manila, Philippines March 2-4, 2015 A Historical Evaluation of The Emergence of Nueva Ecija as the Rice Granary of the Philippines Fernando A. Santiago, Jr., Ph.D. Department of History De La Salle University [email protected] Abstract: The recognition of Nueva Ecija’s potential as a seedbed for rice in the latter half of the nineteenth century led to the massive conversion of public land and the establishment of agricultural estates in the province. The emergence of these estates signalled the arrival of wide scale commercial agriculture that revolved around wet- rice cultivation. By the 1920s, Nueva Ecija had become the “Rice Granary of the Philippines,” which has been the identity of the province ever since. This study is an assessment of the emergence of Nueva Ecija as the leading rice producer of the country. It also tackles various facets of the rice industry, the profitability of the crop and some issues that arose from rice being a controlled commodity. While circumstances might suggest that the rice producers would have enjoyed tremendous prosperity, it was not the case for the rice trade was in the hands of middlemen and regulated by the government. The government policy which favored the urban consumers over rice producers brought meager profits, which led to disappointment to all classes and ultimately caused social tension in the province. The study therefore also explains the conditions that made Nueva Ecija the hotbed of unrest prior to the Second World War. Historical methodology was applied in the conduct of the study. -

Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population AURORA

2010 Census of Population and Housing Aurora Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population AURORA 201,233 BALER (Capital) 36,010 Barangay I (Pob.) 717 Barangay II (Pob.) 374 Barangay III (Pob.) 434 Barangay IV (Pob.) 389 Barangay V (Pob.) 1,662 Buhangin 5,057 Calabuanan 3,221 Obligacion 1,135 Pingit 4,989 Reserva 4,064 Sabang 4,829 Suclayin 5,923 Zabali 3,216 CASIGURAN 23,865 Barangay 1 (Pob.) 799 Barangay 2 (Pob.) 665 Barangay 3 (Pob.) 257 Barangay 4 (Pob.) 302 Barangay 5 (Pob.) 432 Barangay 6 (Pob.) 310 Barangay 7 (Pob.) 278 Barangay 8 (Pob.) 601 Calabgan 496 Calangcuasan 1,099 Calantas 1,799 Culat 630 Dibet 971 Esperanza 458 Lual 1,482 Marikit 609 Tabas 1,007 Tinib 765 National Statistics Office 1 2010 Census of Population and Housing Aurora Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population Bianuan 3,440 Cozo 1,618 Dibacong 2,374 Ditinagyan 587 Esteves 1,786 San Ildefonso 1,100 DILASAG 15,683 Diagyan 2,537 Dicabasan 677 Dilaguidi 1,015 Dimaseset 1,408 Diniog 2,331 Lawang 379 Maligaya (Pob.) 1,801 Manggitahan 1,760 Masagana (Pob.) 1,822 Ura 712 Esperanza 1,241 DINALUNGAN 10,988 Abuleg 1,190 Zone I (Pob.) 1,866 Zone II (Pob.) 1,653 Nipoo (Bulo) 896 Dibaraybay 1,283 Ditawini 686 Mapalad 812 Paleg 971 Simbahan 1,631 DINGALAN 23,554 Aplaya 1,619 Butas Na Bato 813 Cabog (Matawe) 3,090 Caragsacan 2,729 National Statistics Office 2 2010 Census of Population and -

1TT Ilitary ISTRICT 15 APRIL 1944 ENERAL HEADQU Rtilrs SQUI WES F2SPA LCEIC AREA Mitiaryi Intcligee Sectionl Ge:;;Neral Staff

. - .l AU 1TT ILiTARY ISTRICT 15 APRIL 1944 ENERAL HEADQU RTiLRS SQUI WES F2SPA LCEIC AREA Mitiaryi IntcligeE Sectionl Ge:;;neral Staff MINDA NAO AIR CENTERS 0) 5 0 10 20 30 SCALE IN MILS - ~PROVI~CIAL BOUNDARIEtS 1ST& 2ND CGLASS ROADIS h A--- TRAILS OPERATIONAL AIRDROMES O0 AIRDROMES UNDER CONSTRUCTION 0) SEAPLANE BASES (KNO N) _ _ _ _ 2 .__. ......... SITUATION OF FRIENDLY AR1'TED ORL'S IN TIDE PHILIPPINES 19 Luzon, Mindoro, Marinduque and i asbate: a) Iuzon: Pettit, Shafer free Luzon, Atwell & Ramsey have Hq near Antipolo, Rizal, Frank Johnson (Liguan Coal Mines), Rumsel (Altaco Transport, Rapu Rapu Id), Dick Wisner (Masbate Mines), all on Ticao Id.* b) IlocoseAbra: Number Americans free this area.* c) Bulacan: 28 Feb: 40 men Baliuag under Lt Pacif ico Cabreras. 8ev guerr loaders Bulacan, largest being under Lorenzo Villa, ox-PS, 1"x/2000 well armed men in "77th Regt".., BC co-op w/guerr thruout the prov.* d) Manila: 24 Mar: FREE PHILIPPITS has excellent coverage Manila, Bataan, Corregidor, Cavite, Batangas, Pampanga, Pangasinan, Tayabas, La Union, and larger sirbases & milit installations.* e) Tayabas: 19 Mar: Gen Gaudencia Veyra & guerr hit 3 towns on Bondoc Penin: Catanuan, Macal(lon & Genpuna && occu- pied them. Many BC reported killed,* f) icol Peninsula : 30 Mar: Oupt Zabat claims to have uni-s fied all 5th MD but Sorsogon.* g) Masbate: 2 Apr Recd : Villajada unit killed off by i.Maj Tanciongco for bribe by Japs.,* CODvjTNTS: (la) These men, but Ramsey, not previously reported. Ramsey previously reported in Nueva Ecija. (lb) Probably attached to guerrilla forces under Gov, Ablan. -

Over Land and Over Sea: Domestic Trade Frictions in the Philippines – Online Appendix

ONLINE APPENDIX Over Land and Over Sea: Domestic Trade Frictions in the Philippines Eugenia Go 28 February 2020 A.1. DATA 1. Maritime Trade by Origin and Destination The analysis is limited to a set of agricultural commodities corresponding to 101,159 monthly flows. About 5% of these exhibit highly improbable derived unit values suggesting encoding errors. More formally, provincial retail and farm gate prices are used as upper and lower bounds of unit values to check for outliers. In such cases, more weight is given to the volume record as advised by the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA), and values were adjusted according to the average unit price of the exports from the port of the nearest available month before and after the outlier observation. 2. Interprovince Land Trade Interprovince land trade flows were derived using Marketing Cost Structure Studies prepared by the Bureau of Agricultural Statistics for a number of products in selected years. These studies identify the main supply and destination provinces for certain commodities. The difference between production and consumption of a supply province is assumed to be the amount available for export to demand provinces. The derivation of imports of a demand province is straightforward when an importing province only has one source province. In cases where a demand province sources from multiple suppliers, such as the case of the National Capital Region (NCR), the supplying provinces are weighted according to the sample proportions in the survey. For example, NCR sources onions from Ilocos Norte, Pangasinan, and Nueva Ecija. Following the sample proportion of traders in each supply province, it is assumed that 26% of NCR imports came from Ilocos Norte, 34% from Pangasinan, and 39% from Nueva Ecija. -

Flood Risk Assessment Under the Climate Change in the Case of Pampanga River Basin, Philippines

FLOOD RISK ASSESSMENT UNDER THE CLIMATE CHANGE IN THE CASE OF PAMPANGA RIVER BASIN, PHILIPPINES Santy B. Ferrer* Supervisor: Mamoru M. Miyamoto** MEE133631 Advisors: Maksym Gusyev*** Miho Ohara**** ABSTRACT The main objective of this study is to assess the flood risk in the Pampanga river basin that consists of the flood hazard, exposure, and risk in terms of potential flood fatalities and economic losses under the climate change. The Rainfall-Runoff-Inundation (RRI) model was calibrated using 2011 flood and validated with the 2009, 2012 and 2013 floods. The calibrated RRI model was applied to produce flood inundation maps based on 10-, 25, 50-, and 100-year return period of 24-hr rainfall. The rainfall data is the output of the downscaled and bias corrected MRI -AGCM3.2s for the current climate conditions (CCC) and two cases of future climate conditions with an outlier in the dataset (FCC-case1) and without an outlier (FCC-case2). For this study, the exposure assessment focuses on the affected population and the irrigated area. Based on the results, there is an increasing trend of flood hazard in the future climate conditions, therefore, the greater exposure of the people and the irrigated area keeping the population and irrigated area constant. The results of this study may be used as a basis for the climate change studies and an implementation of the flood risk management in the basin. Keywords: Risk assessment, Pampanga river basin, Rainfall-Runoff-Inundation model, climate change, MRI-AGCM3.2S 1. INTRODUCTION The Pampanga river basin is the fourth largest basin in the Philippines located in the Central Luzon Region with an approximate area of 10,545 km² located in the Central Luzon Region. -

Climate-Responsive Integrated Master Plan for Cagayan River Basin

Climate-Responsive Integrated Master Plan for Cagayan River Basin VOLUME I - EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Submitted by College of Forestry and Natural Resources University of the Philippines Los Baños Funded by River Basin Control Office Department of Environment and Natural Resources CLIMATE-RESPONSIVE INTEGRATED RIVER BASIN MASTER PLAN FOR THE i CAGAYAN RIVER BASIN Table of Contents 1 Rationale .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 2 Objectives of the Study .............................................................................................................................. 1 3 Scope .................................................................................................................................................................. 1 4 Methodology .................................................................................................................................................. 2 5 Assessment Reports ................................................................................................................................... 3 5.1 Geophysical Profile ........................................................................................................................... 3 5.2 Bioecological Profile ......................................................................................................................... 6 5.3 Demographic Characteristics ...................................................................................................... -

Notes on Current Health and Health

Addendum : Notes on current health and health –related programs in the Philippines – Implications on the Reproductive Roles of Indgenous Women (c2-24-16) -- The government’s allocation for health is now the highest for 2016. However the failure to achieve the MDGs 4 and 5 is attributed to the basic lack of accountaBility of the government to invest in the long-term Benefit of the poor Filipinos through provision of Basic necessities to facilitate effective health delivery to Filipinos, especially to the marginalized sector. According to Folger (2015), in her article for aspiring expats to the Philippines: “In the Philippines, the reports notes, the level of per-person healthcare spending is one of the lowest among Southeast Asia’s major economies. At 4.6%, the same holds true for spending as a proportion of GDP. Due to weak public financing, that number is expected to drop to 4.5% by 2018. At the same time, the nation’s healthcare spending is projected to increase an average of 8% annually, from an estimated $12.5 billion in 2013 to $20 billion in 2018. To address the growing need for improved healthcare coverage, the government in 2013 passed the Universal Healthcare Bill, which promises health insurance for all Philippine nationals, especially the poor”. Still prevalent up to now is shortage of medical personnel in the Philippines, in general, more so in rural areas. According to Folger (2015): “Another challenge facing many countries in Southeast Asia is the chronic shortage of medical personnel. The average number of physicians in Southeast Asia is 0.6 per 1,000 people; in the Philippines, that figure is slightly higher at approximately one physician per 1,000 Filipinos. -

REGIONAL PROFILE Region 3 Or Central Luzon Covers the Provinces of Bulacan, Pampanga, Tarlac, Nueva Ecija, Bataan, Zambales

REGIONAL PROFILE Region 3 or Central Luzon covers the provinces of Bulacan, Pampanga, Tarlac, Nueva Ecija, Bataan, Zambales and Aurora. It has a total land area of 2,215,752 hectares. The region is endowed with a balanced mix of environmental assets to value, maintain, develop and manage accordingly. It is composed of 494,533 hectares of forestland, 251,518 hectares of protected areas composed of watersheds and forest reserves, national parks, games refuge, bird sanctuary and wildlife area covering 13.8% of the region’s land area. Forty one percent of its land area is composed of agricultural plains with rice as its main crop. Long coastlines rich with fishing grounds border it. Mineral resources may be extracted in Bulacan and Zambales Central Luzon is traditionally known as the Rice Bowl of the Philippines due to its vast rice lands that produces most of the nation’s staple food products as well as a wide variety of other crops. With the opening of various investment opportunities in Economic Zones in Clarkfield and Subic Bay Area, Region III is now termed as the W-Growth Corridor due to the industrialization of many areas in the region. The W-Growth Corridor covers areas with rapid growth potentials for the industrial, tourism and agricultural sectors of Central Luzon, making Region III one of the most critical regions in terms of environmental concerns primarily due to the rapid sprawl of industries/establishments and human settlements while the necessary land use and environmental planning are not yet effectively being carved. [As such, the EMB, together with Local Government Units (LGUs) and other entities are trying to lessen the impact of infrastructure development and industrialization on the environment. -

Media Update

Media Update MEDIA UPDATE Effects of Tropical Depression “Winnie” As of December 1, 2004 11:30 AM A. Background The continuous monsoon rains brought about by Tropical Depression “Winnie” triggered massive floodings in the low-lying areas of the provinces of Bulacan, Nueva Ecija, Aurora, Quezon, Camarines Norte, Rizal and Metro Manila particularly Quezon City, Marikina City, San Juan and Malabon affecting 37,418 families or 168,214 persons in 114 barangays of 31 municipalities. These had also resulted to 182 persons deaths and 27 injured. The floodwaters ranging from five (5) meters to knee/house-deep rendered roads and bridges impassable to all types of vehicles. B. Emergency Management Activities 1. Damage and Needs Assessment 1.1 Profile of Areas and Population Affected ( Source : Local DCCs) Region/Province No. of Mun No of Bgys Affected Fam Per Region II 3 18 424 1,793 Isabela 3 18 424 1,793 1 Region III 23 83 33,123 148,566 Bulacan 10 35 8 ,515 51,087 Nueva Ecija 8 Cabanatuan City 40 12,556 35,130 Palayan City 8 1,086 4,837 Aurora 5 10,966 57,511 Media Update Region IV 6 6 1,409 7,045 Quezon (for 3 1 validation) Rizal 3 5 1,409 7,045 Region V 1 Camarines Sur 1 NCR 2 7 2,462 10,810 Metro Manila 2 Marikina City 4 722 3,610 Quezon City 1 40 200 Pasig City 2 1,700 6,800 Grand –Total 31 114 37,418 168,214 Note: During the passage of Tropical Depression Winnie, there were 584 passengers, and 17 rolling cargoes stranded in the terminals of Tabaco, Albay; Virac, Catanduanes; and Sabang, Camarines Sur, all in Region V. -

JICA Philippines Operations Map

JICA Philippines Operations Map 6466 JICA Philippines Annual Report 2019 JICA Philippines Project List (Ongoing projects as of December 2019) Priority Area: Achieving economic growth Priority Area: Overcoming vulnerability Diesel Fuel with Renergy System in Boracay island through further promotion of investment and stabilizing bases for human life and BORACAY ISLAND 54. Project for Enhancing Solid Waste Management in production activity GOVERNANCE Davao City DAVAO CITY 55. Project on Promoting Sustainable Reduce, Reuse, 1. The Project for Enhancement of Philippine Coast DISASTER RISK REDUCTION AND MANAGEMENT and Recycle (3Rs) System through Education Guard Capability on Vessel Operation, Maintenance 30. Pasig Marikina River Channel Improvement Project to Produce Environment-Minded Society for Planning and Maritime Law Enforcement METRO (Phase IV) METRO MANILA Development BOHOL MANILA 31. Flood Risk Management Project for Cagayan River, 56. Plastic Recycling Project for Improving Women’s 2. Maritime Safety Capability Improvement Project Tagoloan River, and Imus River CAGAYAN, MISAMIS (Phase I and II) NATIONWIDE Income in Tagbilaran City BOHOL ORIENTAL, CAVITE 57. Ensuring Children’s Potential for Development and 3. Improvement of TV Programs of People’s Television 32. Flood Risk Management Project for Cagayan de Independence through Improved Residential Care Network METRO MANILA Oro River CAGAYAN DE ORO Practices PAMPANGA, OLONGAPO, METRO MANILA 33. Cavite Industrial Area Flood Risk Management 58. Project on Knowledge Dissemination and Actual ECONOMIC INFRASTRUCTURE Project CAVITE Implementation of Preventive Care Program for 4. The Project on Improvement of Quality 34. Promotion of School Disaster Risk Reduction and the Senior Citizens of Capas Municipality TARLAC Management for Road and Bridge Construction Management in Cebu CEBU 59. -

The Case of Selected Communities in Talugtug, Nueva Ecija, Philippines

The CGPRT Centre The Regional Co-ordination Centre for Research and Development of Coarse Grains, Pulses, Roots and Tuber Crops in the Humid Tropics of Asia and the Pacific (CGPRT Centre) was established in 1981 as a subsidiary body of UN/ESCAP. Objectives In co-operation with ESCAP member countries, the Centre will initiate and promote research, training and dissemination of information on socio-economic and related aspects of CGPRT crops in Asia and the Pacific. In its activities, the Centre aims to serve the needs of institutions concerned with planning, research, extension and development in relation to CGPRT crop production, marketing and use. Programmes In pursuit of its objectives, the Centre has two interlinked programmes to be carried out in the spirit of technical cooperation among developing countries: 1. Research and development which entails the preparation and implementation of projects and studies covering production, utilization and trade of CGPRT crops in the countries of Asia and the South Pacific. 2. Human resource development and collection, processing and dissemination of relevant information for use by researchers, policy makers and extension workers. CGPRT Centre Working Papers currently available: Working Paper No. 58 Food Security Strategies for Vanuatu by Shadrack R. Welegtabit Working Paper No. 59 Integrated Report: Food Security Strategies for Selected South Pacific Island Countries by Pantjar Simatupang and Euan Fleming Working Paper No. 60 CGPRT Crops in the Philippines: A Statistical Profile 1990-1999 by Mohammad A.T. Chowdhury and Muhamad Arif Working Paper No. 61 Stabilization of Upland Agriculture under El Nino Induced Climatic Risk: Impact Assessment and Mitigation Measures in Malaysia by Ariffin bin Tawang, Tengku Ariff bin Tengku Ahmad and Mohd. -

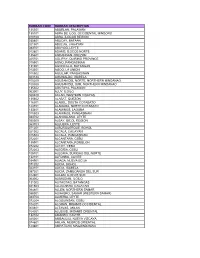

Rurban Code Rurban Description 135301 Aborlan

RURBAN CODE RURBAN DESCRIPTION 135301 ABORLAN, PALAWAN 135101 ABRA DE ILOG, OCCIDENTAL MINDORO 010100 ABRA, ILOCOS REGION 030801 ABUCAY, BATAAN 021501 ABULUG, CAGAYAN 083701 ABUYOG, LEYTE 012801 ADAMS, ILOCOS NORTE 135601 AGDANGAN, QUEZON 025701 AGLIPAY, QUIRINO PROVINCE 015501 AGNO, PANGASINAN 131001 AGONCILLO, BATANGAS 013301 AGOO, LA UNION 015502 AGUILAR, PANGASINAN 023124 AGUINALDO, ISABELA 100200 AGUSAN DEL NORTE, NORTHERN MINDANAO 100300 AGUSAN DEL SUR, NORTHERN MINDANAO 135302 AGUTAYA, PALAWAN 063001 AJUY, ILOILO 060400 AKLAN, WESTERN VISAYAS 135602 ALABAT, QUEZON 116301 ALABEL, SOUTH COTABATO 124701 ALAMADA, NORTH COTABATO 133401 ALAMINOS, LAGUNA 015503 ALAMINOS, PANGASINAN 083702 ALANGALANG, LEYTE 050500 ALBAY, BICOL REGION 083703 ALBUERA, LEYTE 071201 ALBURQUERQUE, BOHOL 021502 ALCALA, CAGAYAN 015504 ALCALA, PANGASINAN 072201 ALCANTARA, CEBU 135901 ALCANTARA, ROMBLON 072202 ALCOY, CEBU 072203 ALEGRIA, CEBU 106701 ALEGRIA, SURIGAO DEL NORTE 132101 ALFONSO, CAVITE 034901 ALIAGA, NUEVA ECIJA 071202 ALICIA, BOHOL 023101 ALICIA, ISABELA 097301 ALICIA, ZAMBOANGA DEL SUR 012901 ALILEM, ILOCOS SUR 063002 ALIMODIAN, ILOILO 131002 ALITAGTAG, BATANGAS 021503 ALLACAPAN, CAGAYAN 084801 ALLEN, NORTHERN SAMAR 086001 ALMAGRO, SAMAR (WESTERN SAMAR) 083704 ALMERIA, LEYTE 072204 ALOGUINSAN, CEBU 104201 ALORAN, MISAMIS OCCIDENTAL 060401 ALTAVAS, AKLAN 104301 ALUBIJID, MISAMIS ORIENTAL 132102 AMADEO, CAVITE 025001 AMBAGUIO, NUEVA VIZCAYA 074601 AMLAN, NEGROS ORIENTAL 123801 AMPATUAN, MAGUINDANAO 021504 AMULUNG, CAGAYAN 086401 ANAHAWAN, SOUTHERN LEYTE