Ghost Prisoner Two Years in Secret CIA Detention

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Day Two of Military Judge Questioning 9/11 Accused About Self-Representation

Public amnesty international USA Guantánamo: Day two of military judge questioning 9/11 accused about self-representation 11 July 2008 AI Index: AMR 51/077/2008 On 10 July 2008, military commission judge US Marine Colonel Ralph Kohlmann held further proceedings to question the men accused of orchestrating the attacks of 11 September 2001 about their decision to represent themselves at their forthcoming death penalty trial in the US Naval Base in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba. Amnesty International had an observer at the proceedings. The primary purpose of the hearings was to inquire of each of the accused individually about whether they had been intimidated before or during their arraignment on 5 June 2008 into making a choice to represent themselves, or whether this decision had been made knowingly and voluntarily. Judge Kohlmann had questioned two of the accused, ‘Ali ‘Abd al-‘Aziz ‘Ali (‘Ammar al Baluchi) and Mustafa al Hawsawi at individual sessions held on 9 July (see http://www.amnesty.org/en/library/info/AMR51/076/2008/en). He had scheduled sessions for the other three men, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, Walid bin Attash and Ramzi bin al-Shibh on 10 July. In the event, Ramzi bin al-Shibh refused to come to his session. It seems unlikely that the military judge will question him again on the matter of legal representation until the issue of Ramzi bin al-Shibh’s mental competency is addressed at a hearing scheduled to take place next month (see http://www.amnesty.org/en/library/info/AMR51/074/2008/en). Both Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and Walid bin Attash denied that they had been intimidated or that any intimidation had taken place. -

Observer Dispatch by Mary Ann Walker

Interrogating the Interrogator at Guantánamo Bay GTMO OBSERVER PROGRAM FEBRUARY 5, 2020 By: Mary Ann Walker As part of the Pacific Council’s Guantánamo Bay Observer Program, I traveled to Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, in January 2020 to attend the 9/11 military pre-trial hearing of alleged plotter and mastermind Khalid Sheik Mohammad and four others charged with assisting in the 9/11 attacks: Walid bin Attash, Ramzi bin al-Shibh, Ali Abdul Aziz Ali, and Mustafa al-Hawsawi. Pretrial hearings have been ongoing in Guantánamo Bay since 2008. The trial itself is scheduled to begin in January 2021, nearly 20 years after the 9/11 attacks. I was among 13 NGO observers from numerous organizations. Media outlets including Al Jazeera, The Guardian, the Los Angeles Times, and The New York Times were also present in order to cover this historic hearing along with many family members of the 9/11 victims. It was an eye-opening experience to be an observer. Defense attorney for Ali Abdul Aziz Ali, James Connell, met with the NGOs and media the evening we arrived on January 18. He explained the current status of pretrial hearings and what we could expect in the days to come. Chief Defense Counsel General John Baker met with the NGOs on Martin Luther King, Jr., Day to give background on the upcoming trial and military commissions. At the start of the meeting, Baker commended Pacific Council on International Policy for its excellent work on the three amendments to the FY2018 defense bill allowing for transparent and fair military commission trials in Guantánamo Bay, which includes the broadcast of the trials via the internet. -

Trying Terrorists Brian S

William Mitchell Law Review Volume 34 Article 6 Issue 5 Journal of the National Security Forum 2008 Trying Terrorists Brian S. Carter-Stiglitz Follow this and additional works at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr Part of the Military, War, and Peace Commons, and the National Security Law Commons Recommended Citation Carter-Stiglitz, Brian S. (2008) "Trying Terrorists," William Mitchell Law Review: Vol. 34: Iss. 5, Article 6. Available at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr/vol34/iss5/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at Mitchell Hamline Open Access. It has been accepted for inclusion in William Mitchell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Mitchell Hamline Open Access. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Mitchell Hamline School of Law Carter-Stiglitz: Trying Terrorists TRYING TERRORISTS Brian S. Carter-Stiglitz Trying terrorists in Article III courts presents a host of complications and problems. As terrorism cases come before civilian courts, prosecutors have had to wrestle with these challenges. The most significant challenge may be the tension between protecting national-security secrets and prosecuting those who threaten national security in open court. The Classified Information Procedures Act (CIPA) is the main litigation tool for dealing with these challenges. Two cases, both with Minnesota roots, demonstrate the challenges that face civil prosecution in terrorism cases. Mohammed Abdullah Warsame, a largely unknown name, is being tried in the District of Minnesota on material support charges. Michael Ward, a former assistant U.S. Attorney (AUSA) for the District of Minnesota, initially led Warsame's prosecution.' The complications caused by CIPA have already prolonged Warsame's prosecution for four years-with no end currently in sight. -

9/11 Report”), July 2, 2004, Pp

Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page i THE 9/11 COMMISSION REPORT Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page v CONTENTS List of Illustrations and Tables ix Member List xi Staff List xiii–xiv Preface xv 1. “WE HAVE SOME PLANES” 1 1.1 Inside the Four Flights 1 1.2 Improvising a Homeland Defense 14 1.3 National Crisis Management 35 2. THE FOUNDATION OF THE NEW TERRORISM 47 2.1 A Declaration of War 47 2.2 Bin Ladin’s Appeal in the Islamic World 48 2.3 The Rise of Bin Ladin and al Qaeda (1988–1992) 55 2.4 Building an Organization, Declaring War on the United States (1992–1996) 59 2.5 Al Qaeda’s Renewal in Afghanistan (1996–1998) 63 3. COUNTERTERRORISM EVOLVES 71 3.1 From the Old Terrorism to the New: The First World Trade Center Bombing 71 3.2 Adaptation—and Nonadaptation— ...in the Law Enforcement Community 73 3.3 . and in the Federal Aviation Administration 82 3.4 . and in the Intelligence Community 86 v Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page vi 3.5 . and in the State Department and the Defense Department 93 3.6 . and in the White House 98 3.7 . and in the Congress 102 4. RESPONSES TO AL QAEDA’S INITIAL ASSAULTS 108 4.1 Before the Bombings in Kenya and Tanzania 108 4.2 Crisis:August 1998 115 4.3 Diplomacy 121 4.4 Covert Action 126 4.5 Searching for Fresh Options 134 5. -

Radical Milieus and Salafis Movements in France: Ideologies, Practices, Relationships with Society and Political Visions

MWP 2014 /13 Max Weber Programme Radical Milieus and Salafis Movements in France: Ideologies, Practices, Relationships with Society and Political Visions AuthorMohamed-Ali Author Adraouiand Author Author European University Institute Max Weber Programme Radical Milieus and Salafis Movements in France: Ideologies, Practices, Relationships with Society and Political Visions Mohamed-Ali Adraoui EUI Working Paper MWP 2014/13 This text may be downloaded for personal research purposes only. Any additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copy or electronically, requires the consent of the author(s), editor(s). If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the working paper or other series, the year, and the publisher. ISSN 1830-7728 © Mohamed-Ali Adraoui, 2014 Printed in Italy European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy www.eui.eu cadmus.eui.eu Abstract This paper deals mainly with the issue of radical Islam within French society over recent decades. More particularly, this study illustrates evolutions and the radicalization processes among some militant Islamic groups in this country since the end of the 1970s. Focusing on connections between geopolitical issues born in the Arab world and their implications within a predominantly non Muslim society, enables highlighting the centrality of some actors and currents that have been the impulse for the emergence of a radical and militant activism in France. Some specific attention is paid to Salafist movements, whether they are primarily interested in political protest or whether they desire first to break with the rest of society in order to purify their beliefs and social relations.This paper has to do with the political vision, strategies, history and sociology of Islamic radical militancy in France. -

Hearing for Majid Khan

C05403115 o (b)(1) (b)(3) Verbatim Transcript of Combatant Status Review Tribnnal Hearing for ISN 10020 OPENING PRESIDENT: This hearing shall come to order. RECORDER: This Tribunal is being conducted at 08:42 on 15 April 2007 on board U.S. Naval Base Guantanarno Bay, Cuba. The following personnel are present: Colonel United States Air Force, President, Commander United States Navy, Member, Lieutenant Colonel United States Air Force, Member, Major United States Air Force, Personal Representative, Sergeant First Class United States Army, Reporter, Major_United States Air Force, Recorder. Lieutenant Colonel_is the Judge Advocate member ofthe Tribunal. OATH SESSION 1 RECORDER: All rise. PRESIDENT: The Recorder will be sworn. Do you, Major-swear or affirm that you will faithfully perform the duties as ~signed in this Tribunal, so help you God? RECORDER: I do. PRESIDENT: The Reporter will now be sworn. The Recorder will administer the oath. RECORDER: Do you, Sergeant First Class swear that you will faithfully discharge your duties as Reporter assigned in this Tribunal, so help you God? REPORTER: [ do. PRESIDENT: We'll take a briefrecess while the Detainee is brought into the room. RECORDER: The time is 08:43 on IS Apri12007. This Tribunal is now in recess. All rise. [All personnel depart the room.] CONVENING AUTHORITY RECORDER: [All personnel return into the room at 08:48.] All rise. PRESIDENT: This hearing will come to order. You may be seated. Good morning. DETAINEE: Good morning. How are you guys doing? ISN # 10020 Enclosure (3) Page1 of50 C05403115 PRESIDENT: Very good, fine, thank you. This Tribunal is convened by order ofthe Director, Combatant Status Review Tribunals under the provisions ofhis Order of 12 February 2007. -

True and False Confessions: the Efficacy of Torture and Brutal

Chapter 7 True and False Confessions The Efficacy of Torture and Brutal Interrogations Central to the debate on the use of “enhanced” interrogation techniques is the question of whether those techniques are effective in gaining intelligence. If the techniques are the only way to get actionable intelligence that prevents terrorist attacks, their use presents a moral dilemma for some. On the other hand, if brutality does not produce useful intelligence — that is, it is not better at getting information than other methods — the debate is moot. This chapter focuses on the effectiveness of the CIA’s enhanced interrogation technique program. There are far fewer people who defend brutal interrogations by the military. Most of the military’s mistreatment of captives was not authorized in detail at high levels, and some was entirely unauthorized. Many military captives were either foot soldiers or were entirely innocent, and had no valuable intelligence to reveal. Many of the perpetrators of abuse in the military were young interrogators with limited training and experience, or were not interrogators at all. The officials who authorized the CIA’s interrogation program have consistently maintained that it produced useful intelligence, led to the capture of terrorist suspects, disrupted terrorist attacks, and saved American lives. Vice President Dick Cheney, in a 2009 speech, stated that the enhanced interrogation of captives “prevented the violent death of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of innocent people.” President George W. Bush similarly stated in his memoirs that “[t]he CIA interrogation program saved lives,” and “helped break up plots to attack military and diplomatic facilities abroad, Heathrow Airport and Canary Wharf in London, and multiple targets in the United States.” John Brennan, President Obama’s recent nominee for CIA director, said, of the CIA’s program in a televised interview in 2007, “[t]here [has] been a lot of information that has come out from these interrogation procedures. -

The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: an Empirical Study

© Reuters/HO Old – Detainees at XRay Camp in Guantanamo. The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: An Empirical Study Benjamin Wittes and Zaahira Wyne with Erin Miller, Julia Pilcer, and Georgina Druce December 16, 2008 The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: An Empiricial Study Table of Contents Executive Summary 1 Introduction 3 The Public Record about Guantánamo 4 Demographic Overview 6 Government Allegations 9 Detainee Statements 13 Conclusion 22 Note on Sources and Methods 23 About the Authors 28 Endnotes 29 Appendix I: Detainees at Guantánamo 46 Appendix II: Detainees Not at Guantánamo 66 Appendix III: Sample Habeas Records 89 Sample 1 90 Sample 2 93 Sample 3 96 The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: An Empiricial Study EXECUTIVE SUMMARY he following report represents an effort both to document and to describe in as much detail as the public record will permit the current detainee population in American T military custody at the Guantánamo Bay Naval Station in Cuba. Since the military brought the first detainees to Guantánamo in January 2002, the Pentagon has consistently refused to comprehensively identify those it holds. While it has, at various times, released information about individuals who have been detained at Guantánamo, it has always maintained ambiguity about the population of the facility at any given moment, declining even to specify precisely the number of detainees held at the base. We have sought to identify the detainee population using a variety of records, mostly from habeas corpus litigation, and we have sorted the current population into subgroups using both the government’s allegations against detainees and detainee statements about their own affiliations and conduct. -

Islamist Extremism in Europe

Order Code RS22211 Updated January 6, 2006 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Islamist Extremism in Europe Kristin Archick (Coordinator), John Rollins, and Steven Woehrel Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Summary Although the vast majority of Muslims in Europe are not involved in radical activities, Islamist extremists and vocal fringe communities that advocate terrorism exist and reportedly have provided cover for terrorist cells. Germany and Spain were identified as key logistical and planning bases for the September 11, 2001, attacks on the United States. The March 2004 terrorist bombings in Madrid have been attributed to an Al Qaeda-inspired group of North Africans. And UK authorities are investigating suspected Al Qaeda support to the British perpetrators of the July 7, 2005, terrorist attacks on London. This report provides an overview of Islamist extremism in Europe, possible terrorist links, European responses, and implications for the United States. It will be updated as needed. See also CRS Report RL31612, European Counterterrorist Efforts: Political Will and Diverse Responses in the First Year after September 11, and CRS Report RL33166, Muslims in Europe: Integration in Selected Countries, by Paul Gallis. Background: Europe’s Muslim Communities1 Estimates of the number of Muslims in Europe vary widely, depending on the methodology and definitions used, and the geographical limits imposed. Excluding Turkey and the Balkans, researchers estimate that as many as 15 to 20 million Muslims live on the European continent. Muslims are the largest religious minority in Europe, and Islam is the continent’s fastest growing religion. Substantial Muslim populations exist in Western European countries, including France, Germany, the United Kingdom, Spain, Italy, the Netherlands, and Belgium. -

Homeland Security Implications of Radicalization

THE HOMELAND SECURITY IMPLICATIONS OF RADICALIZATION HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE, INFORMATION SHARING, AND TERRORISM RISK ASSESSMENT OF THE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION SEPTEMBER 20, 2006 Serial No. 109–104 Printed for the use of the Committee on Homeland Security Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/index.html U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 35–626 PDF WASHINGTON : 2008 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY PETER T. KING, New York, Chairman DON YOUNG, Alaska BENNIE G. THOMPSON, Mississippi LAMAR S. SMITH, Texas LORETTA SANCHEZ, California CURT WELDON, Pennsylvania EDWARD J. MARKEY, Massachusetts CHRISTOPHER SHAYS, Connecticut NORMAN D. DICKS, Washington JOHN LINDER, Georgia JANE HARMAN, California MARK E. SOUDER, Indiana PETER A. DEFAZIO, Oregon TOM DAVIS, Virginia NITA M. LOWEY, New York DANIEL E. LUNGREN, California ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON, District of JIM GIBBONS, Nevada Columbia ROB SIMMONS, Connecticut ZOE LOFGREN, California MIKE ROGERS, Alabama SHEILA JACKSON-LEE, Texas STEVAN PEARCE, New Mexico BILL PASCRELL, JR., New Jersey KATHERINE HARRIS, Florida DONNA M. CHRISTENSEN, U.S. Virgin Islands BOBBY JINDAL, Louisiana BOB ETHERIDGE, North Carolina DAVE G. REICHERT, Washington JAMES R. LANGEVIN, Rhode Island MICHAEL MCCAUL, Texas KENDRICK B. MEEK, Florida CHARLIE DENT, Pennsylvania GINNY BROWN-WAITE, Florida SUBCOMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE, INFORMATION SHARING, AND TERRORISM RISK ASSESSMENT ROB SIMMONS, Connecticut, Chairman CURT WELDON, Pennsylvania ZOE LOFGREN, California MARK E. -

Requests Report

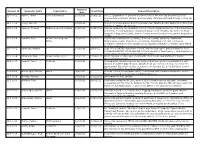

Received Request ID Requester Name Organization Closed Date Request Description Date 12-F-0001 Vahter, Tarmo Eesti Ajalehed AS 10/3/2011 3/19/2012 All U.S. Department of Defense documents about the meeting between Estonian president Arnold Ruutel (Ruutel) and Secretary of Defense Richard Cheney on July 19, 1991. 12-F-0002 Jeung, Michelle - 10/3/2011 - Copies of correspondence from Congresswoman Shelley Berkley and/or her office from January 1, 1999 to the present. 12-F-0003 Lemmer, Thomas McKenna Long & Aldridge 10/3/2011 11/22/2011 Records relating to the regulatory history of the following provisions of the Department of Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (DFARS), the former Defense Acquisition Regulation (DAR), and the former Armed Services Procurement Regulation (ASPR). 12-F-0004 Tambini, Peter Weitz Luxenberg Law 10/3/2011 12/12/2011 Documents relating to the purchase, delivery, testing, sampling, installation, Office maintenance, repair, abatement, conversion, demolition, removal of asbestos containing materials and/or equipment incorporating asbestos-containing parts within its in the Pentagon. 12-F-0005 Ravnitzky, Michael - 10/3/2011 2/9/2012 Copy of the contract statement of work, and the final report and presentation from Contract MDA9720110005 awarded to the University of New Mexico. I would prefer to receive these documents electronically if possible. 12-F-0006 Claybrook, Rick Crowell & Moring LLP 10/3/2011 12/29/2011 All interagency or other agreements with effect to use USA Staffing for human resources management. 12-F-0007 Leopold, Jason Truthout 10/4/2011 - All documents revolving around the decision that was made to administer the anti- malarial drug MEFLOQUINE (aka LARIAM) to all war on terror detainees held at the Guantanamo Bay prison facility as stated in the January 23, 2002, Infection Control Standard Operating Procedure (SOP). -

1 the Dark Truth Behind Gitmo the Twenty-Second Blaine Sloan

The Dark Truth Behind Gitmo The Twenty-Second Blaine Sloan Lecture at Pace Law School – Delivered on November 15, 2009 in White Plains, NY Scott Horton On his second day as president, Barack Obama acted on a promise to close the detention facility that his predecessor opened in Guantánamo. He created an inter-agency task force to advise him on the specifics of this process and to create future guidelines for the detention of terrorism suspects captured abroad. He set a deadline on the accomplishment of this objective: one year. To- day we are two weeks away from the issuance of the inter-agency task force’s report, and media commentators tell us that almost no one expects that his goal of closing the facility in one year can be met. This will be portrayed by some, especially the superficial commentators who populate the Beltway world, as a failure by the administration. But in fact, as we meet here today Attorney General Holder is announcing a series of prosecutions that will go for- ward quickly, one group in federal court in New York, another before a military commission. The framework of the Obama effort is quickly coming into shape. Lessons Learned from Guantánamo Today, I’d like to invite a new look at Guantánamo. And I’ll start by asking a simple question--can we really bring the Guantánamo debacle to a close with- out focusing careful attention on how it was set up and what went on there, and drawing some conclusions about the past? I think the answer to that question is clearly “no.” Yet Barack Obama tells us we need to “look forwards, not backwards.” This has been a regular response to calls for accountability stem- ming from the excesses of the Bush Administration’s war on terror--torture and the mistreatment of prisoners, the operation of black sites and warrantless domestic surveillance.