Bryophytes of UBC Botanical Garden

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bryo's to Know Table

BRYOS TO KNOW Common Name Claim to Fame MOSSES: Bryopsida: Buckiella undulata Snake Moss, Wavy-Leaf aka Plagiothecium undulatum Moss, Tongue-Moss, Wavy Cotton, Moss Claopodium crispifolium Rough moss Dicranum scoparium Broom Moss Dicranum tauricum Finger-licking-good-moss Eurhynchium oreganum Oregon Beaked-Moss aka Kindbergia oregana Eurhynchium praelongum Slender-Beaked Moss aka Kindbergia praelonga Hylocomium splendens Step Moss, Stair-Step Moss, Splendid Feather Moss Grimmia pulvinata Grey-cushioned Grimmia Hypnum circinale Coiled-Leaf Moss Leucolepis acanthoneuron Menzie’s Tree Moss, Umbrella Moss, Palm-Tree Moss Plagiomnium insigne Badge Moss, Coastal Leafy Moss Pseudotaxiphyllum elegans Small-Flat Moss Rhizomnium glabrescens Fan Moss Rhytidiadelphus loreus Lanky Moss, Loreus Goose Neck Moss Rhytidiadelphus squarrosum Springy Turf-Moss, Square Goose Neck Moss Rhytidiadelphus triquetrus Electrified Cat-Tail Moss, Goose Necked Moss Rhytidiopsus robusta Robust mountain moss Schistostega pennata Goblin’s Gold, Luminous Moss Polytrichopsida: Atrichum Atrichum Moss , Crane’s Bill Moss (for Atrichum selwynii) Pogonatum contortum Contorted Pogonatum Moss Polytrichum commune Common Hair Cap Moss Polytrichum piliferum Bristly Haircap Moss Andreaeopsida Andreaea nivalis Granite moss, Lantern moss, Snow Rock Moss Sphagnopsida: Sphagnum capillifolium Red Bog Moss, Small Red Peat Moss Sphagnum papillosum Fat Bog Moss, Papillose sphagnum Sphagnum squarrosum Shaggy Sphagnum, Spread- Leaved Peat Moss Takakiopsida: Takakia lepidoziooides Impossible -

Coptis Trifolia Conservation Assessment

CONSERVATION ASSESSMENT for Coptis trifolia (L.) Salisb. Originally issued as Management Recommendations December 1998 Marty Stein Reconfigured-January 2005 Tracy L. Fuentes USDA Forest Service Region 6 and USDI Bureau of Land Management, Oregon and Washington CONSERVATION ASSESSMENT FOR COPTIS TRIFOLIA Table of Contents Page List of Tables ................................................................................................................................. 2 List of Figures ................................................................................................................................ 2 Summary........................................................................................................................................ 4 I. NATURAL HISTORY............................................................................................................. 6 A. Taxonomy and Nomenclature.......................................................................................... 6 B. Species Description ........................................................................................................... 6 1. Morphology ................................................................................................................... 6 2. Reproductive Biology.................................................................................................... 7 3. Ecological Roles ............................................................................................................. 7 C. Range and Sites -

Residents Meet Election Candidates University RCMP Welcomes

Published by the University Neighbourhoods Association Volume 9, Issue 10 OCTOBER 16, 2018 University RCMP Welcomes Stadium Road Neighbourhood Residents to First Open House Public Consultation: “Reaching a Reasonable Solution” Residents who launched May in the Stadium Road Neighbourhood, and petition concerning Stadium Road once built, it will become the sixth neigh- Neighbourhood development, have bourhood developed at UBC after Hamp- ton Place (1990s), Hawthorn Place (2000s), launched a second petition Chancellor Place (2000s), East Campus (2010s) and Wesbrook Place (2010s). John Tompkins Editor Meanwhile, members of the UBC residen- tial community have expressed objections to what they see as the ballooning size of the SRN project. UBC originally proposed If you have a last-minute opinion on the the size of the residential floor area to be plan options for the proposed residential 993,000 square feet. Then, in an amended neighbourhood on Stadium Road at UBC, version of the plan earlier this year, build- the time to express it is before October 21, ing area rose to 1.5 million square feet. the last date of an online survey. Some residents even believe the project is on its way to 1.8 million square feet. After three weeks of listening to the public Firefighter Mark McCash from Vancouver Hall No.10 at UBC, RCMP officer on everything – from where a new football The Alma Mater Society, which represents Kyle Smith and Staff Sergeant Chuck Lan, University RCMP Detachment field should be located in relation to the 50,000 UBC students, added to size projec- Commander, at University RCMP Detachment Open House at 2990 layout of numerous residential buildings to tions recently by proposing that the current Wesbrook Mall on Saturday, October 13. -

Riparian Bryophytes of the H. J. Andrews Experimental Forest in the Western Cascades, Oregon

The Bryologist 99(2), pp. 226-235 Copyright © 1996 by the American Bryological and Lichenological Society, Inc. Riparian Bryophytes of the H. J. Andrews Experimental Forest in the Western Cascades, Oregon BENGT GUNNAR JONSSON I Department of Forest Science, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331 Abstract. The knowledge of the distribution and habitat demands for bryophytes in the Pacific Northwest is scarce, and few published quantitative accounts of the flora are present. The present paper includes habitat description, elevational range, substrate preference, and frequency esti- mates for more than 130 riparian mosses and liverworts found in old-growth Pseudotsuga-Tsuga forests of the H. J. Andrews Experimental Forest, Oregon. The data are based on 360 samples distributed among 42 sites covering 1st to 5th order streams and 420 to 1250 m. TWINSPAN analysis resulted in 6 sample groups, representing samples from different elevations, geomorphic surfaces, and stream sizes. The most common mosses are Eurhynchium oreganum, Isothecium stoloniferum, Hypnum circinale, and Dicranum fuscescens. Among the hepatics Scapania bolan- deri, Cephalozia lunulifolia, and Porella navicularis are the most abundant species. Most species are rare at both site and sampte gtot (ever; and this is especially true for acrocarps where more than one-third of the observed species occurred in only one or two sites orland samples. Four of the occurring species (i.e., Antitrichia curtipendula, Buxbaumia piperi, Douinia ovata, and Ptili- dium californicum) are listed for special management and/or regional surveys. Bryophytes constitute an important and conspic- a wide range of different substrates, disturbance uous component of old-growth forests in the Pacific patterns, and a moist microclimate are important Northwest (Lesica et al. -

15Th Canadian Symposium

15TH CANADIAN SYMPOSIUM February 22-24 | 2019 The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC Canada 1 Preface 15th Canadian Symposium | February 22-24, 2019 Home Economics | Family Studies | Human Ecology | Family & Consumer Science Education: Issues & Directions The University of British Columbia, AMS Student Nest, Nest 3500, 6133 University Blvd, Vancouver, BC Canada V6T 1Z4 Organizers Dr. Kerry Renwick, University of British Columbia | Dr. Mary Leah de Zwart, University of British Columbia | Ms. Melissa Edstrom, THESA | Dr. Mary Gale Smith, University of British Columbia | Ms. Jennifer Johnson, THESA | Mr. Joe Tong, SHETA Graphic Design | Kirsty Robbins, University of British Columbia Sponsors We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the following: Canadian Home Economics Foundation (CHEF) | Department of Curriculum & Pedagogy, Faculty of Education, UBC | Teachers of Home Economics Specialist Association (THESA) | BC Dairy Association | BC Agriculture in the Classroom Foundation | Surrey Home Economics Teachers Association (SHETA) | Kwantlen Polytechnic University Canadian La Fondation Home Economics canadienne Foundation pour l’Économie familiale Contents Contents 2 Being A Guest On Musqueam Territory 3 Welcome 4 Overview 5 Program 6 Wayfinding UBC 12 2 ▶ 6 sʔi:ɬqəy ̓ qeqən Being A Guest On Musqueam Territory UBC’s Point Grey Campus is located on the traditional, ancestral, and unceded territory of the Musqueam people. The land it is situated on has always been a place of learning for the Musqueam people, who for millennia have passed on their culture, history, and traditions from one generation to the next. It is common at UBC events to begin with an acknowledgment of Musqueam territory. Acknowledging territory is a way of honoring and showing respect to the Musqueam, who have long inhabited this land. -

Heathland Wind Farm Technical Appendix A8.1: Habitat Surveys

HEATHLAND WIND FARM TECHNICAL APPENDIX A8.1: HABITAT SURVEYS JANAURY 2021 Prepared By: Harding Ecology on behalf of: Arcus Consultancy Services 7th Floor 144 West George Street Glasgow G2 2HG T +44 (0)141 221 9997 l E [email protected] w www.arcusconsulting.co.uk Registered in England & Wales No. 5644976 Habitat Survey Report Heathland Wind Farm TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................................................. 1 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 2 1.1 Background .................................................................................................... 2 1.2 Site Description .............................................................................................. 2 2 METHODS .................................................................................................................. 3 2.1 Desk Study...................................................................................................... 3 2.2 Field Survey .................................................................................................... 3 2.3 Survey Limitations .......................................................................................... 5 3 RESULTS .................................................................................................................... 6 3.1 Desk Study..................................................................................................... -

Prescribed Fire Decreases Lichen and Bryophyte Biomass and Alters Functional Group Composition in Pacific Northwest Prairies Author(S): Lalita M

Prescribed Fire Decreases Lichen and Bryophyte Biomass and Alters Functional Group Composition in Pacific Northwest Prairies Author(s): Lalita M. Calabria, Kate Petersen, Sarah T. Hamman and Robert J. Smith Source: Northwest Science, 90(4):470-483. Published By: Northwest Scientific Association DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3955/046.090.0407 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.3955/046.090.0407 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Lalita M. Calabria1, Kate Petersen,The Evergreen State College, 2700 Evergreen Parkway NW, Olympia, Washington 98505 Sarah T. Hamman, The Center for Natural Lands Management, 120 Union Ave SE #215, Olympia, Washington 98501 and Robert J. Smith, Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, 2082 Cordley Hall, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon 97331 Prescribed Fire Decreases Lichen and Bryophyte Biomass and Alters Functional Group Composition in Pacific Northwest Prairies Abstract The reintroduction of fire to Pacific Northwest prairies has been useful for removing non-native shrubs and supporting habitat for fire-adapted plant and animal species. -

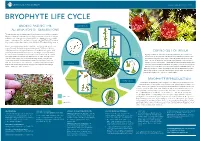

Bryophyte Life Cycle

MARCH 2016LEARNING | VELD & FLORA ABOUT BIODIVERSITY Veld & Flora MARCHFACTSHEET: 2016 | VELD MOSS & FLORA 24 25 3. BRYOPHYTE LIFE CYCLE Gametophyte (n) UNDERSTANDING THE GERMINATION MALE ALTERNATION OF GENERATIONS The way that almost all land plants reproduce is by means of two distinct, alternating life forms, a sexual phase that produces and releases gametes or sex cells and allows fertilisation, and a dispersal phase – both of which are adaptations to an essentially waterless environment. The sexual phase is known as the GAMETOPHYTE or haploid spores (n) generation and the dispersal phase is the SPOROPHYTE or diploid (2n) generation. Mature gametophyte plants produce haploid sex cells (egg and sperm) in sex organs (the male antheridia and female archegonia). These sex cells (also called gametes) fuse during fertilisation to form a diploid (2n) zygote which COPING OUT OF WATER grows, by means of mitosis (that results in two daughter cells each having Sperm (n) the same number and kind of chromosomes as the parent cell), into a new released Bryophytes, which include moss, are primitive plants that give us some idea sporophyte plant. The diploid sporophyte produces haploid (n) spores (i.e. from male of how the first plants that ventured onto land coped with their new waterless FEMALE each spore has a single set of chromosomes) by means of the process environment. They share many features with other plants, but differ in some of cell division called meiosis. Meiosis results in four daughter cells each ways – such as the lack of an effective vascular system (specialised tissue for with half the number of chromosomes of the parent cell. -

The Origin of Alternation of Generations in Land Plants

Theoriginof alternation of generations inlandplants: afocuson matrotrophy andhexose transport Linda K.E.Graham and LeeW .Wilcox Department of Botany,University of Wisconsin, 430Lincoln Drive, Madison,WI 53706, USA (lkgraham@facsta¡.wisc .edu ) Alifehistory involving alternation of two developmentally associated, multicellular generations (sporophyteand gametophyte) is anautapomorphy of embryophytes (bryophytes + vascularplants) . Microfossil dataindicate that Mid ^Late Ordovicianland plants possessed such alifecycle, and that the originof alternationof generationspreceded this date.Molecular phylogenetic data unambiguously relate charophyceangreen algae to the ancestryof monophyletic embryophytes, and identify bryophytes as early-divergentland plants. Comparison of reproduction in charophyceans and bryophytes suggests that the followingstages occurredduring evolutionary origin of embryophytic alternation of generations: (i) originof oogamy;(ii) retention ofeggsand zygotes on the parentalthallus; (iii) originof matrotrophy (regulatedtransfer ofnutritional and morphogenetic solutes fromparental cells tothe nextgeneration); (iv)origin of a multicellularsporophyte generation ;and(v) origin of non-£ agellate, walled spores. Oogamy,egg/zygoteretention andmatrotrophy characterize at least some moderncharophyceans, and arepostulated to represent pre-adaptativefeatures inherited byembryophytes from ancestral charophyceans.Matrotrophy is hypothesizedto have preceded originof the multicellularsporophytes of plants,and to represent acritical innovation.Molecular -

MUSQUEAM NEWSLETTER Tel: 604-263

MUSQUEAM NEWSLETTER Friday July 20, 2018 Tel: 604-263-3261, Toll Free: 1-866-282-3261, Fax: 604-263-4212...Safety Patrol: 604-968-8058 Inside this issue: FIRE BAN 2 MIB JOB POSTINS 3-27 MCC INFO. 28-31 EDUCATION 32-33 HEALTH DEPT. 34-40 Lawn Watering Regulations are in effect May 1 to October 15 HOUSING DEPT. 41-44 STAGE 1 RESIDENTIAL LAWN WATERING ALLOWED: REMAINING NEWS 45-64 Even-numbered addresses Wednesday, Saturday mornings 4 am to 9 am Odd-numbered addresses Thursday, Sunday mornings 4 am to 9 am Watering trees, shrubs and flowers is permitted any day, from 4 am to 9 am if using a sprinkler, or any time if hand watering or us- ing drip irrigation. All hoses must have an automatic shut-off de- vice. These restrictions do not apply to the use of rain water, gray water, any forms of recycled water, or other sources of water outside the GVWD/municipal water supply system. ST. MICHAEL’S CHURCH Water restrictions are set by Metro Vancouver and apply to the use of treated drinking water. Our drinking water comes from rain NO CHURCH UNTIL and snowmelt collected in the Capilano, Seymour, and Coquitlam watersheds. With population growth and climate change, there is increasing pressure on our water supply. Water restrictions help to make sure we have enough treated drinking water for everyone during the dry summer months. Restrictions are in effect May 1 to October 15. AUG. 2018, FATHER PAUL ~~~IS ON VACATION… BC Wild Fire Ban Effective at 12 noon Wednesday, July 18, 2018 within the Coastal Fire Centre’s jurisdiction (BC Parks, Crown lands and private lands), campfires will only be allowed on Northern Vancouver Island, the mid-coast portion of the mainland and on Haida Gwaii. -

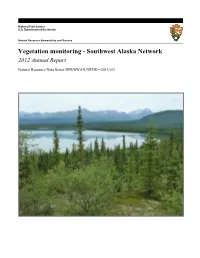

Vegetation Monitoring - Southwest Alaska Network 2012 Annual Report

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Vegetation monitoring - Southwest Alaska Network 2012 Annual Report Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SWAN/NRDS—2013/521 ON THE COVER A white spruce-black spruce (Picea glauca-P. mariana) stand occupies an old burn on the western shore of Two Lakes, Lake Clark National Park and Preserve. Photograph by Amy Miller. Vegetation monitoring - Southwest Alaska Network 2012 Annual Report Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SWAN/NRDS—2013/521 Amy E. Miller and James K. Walton National Park Service Southwest Alaska Network 240 West 5th Avenue Anchorage, AK 99501 August 2013 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado Month Year U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Data Series is intended for the timely release of basic data sets and data summaries. Care has been taken to assure accuracy of raw data values, but a thorough analysis and interpretation of the data has not been completed. Consequently, the initial analyses of data in this report are provisional and subject to change. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. -

Of Mount Sibayak North Sumatra, Indonesia Marchantia

BIOTROPIA Vol. 20 No. 2, 2013: 73 - 80 DOI: 10.11598/btb.2013.20.2.3 THE LIVERWORT GENUS MARCHANTIA (MARCHANTIACEAE) OF MOUNT SIBAYAK NORTH SUMATRA, INDONESIA ETTI SARTINA SIREGAR1,2 , NUNIK S. ARIYANTI 3 , and SRI S.TJITROSOEDIRDJO3,4 1 Plant Biology Graduate Program, Graduate School, Bogor Agricultural University, IPB-Campus Darmaga, Bogor, Indonesia 2University of Sumatra Utara, Medan, Indonesia 3Department of Biology, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Bogor Agricultural University, IPB-Campus Darmaga, Bogor Indonesia 4 SEAMEO BIOTROP, Jl. Raya Tajur km 6, Bogor, Indonesia Received 21 January 2013/Accepted 02 July 2013 ABSTRACT Knowledge on the liverworts (Marchantiophyta) flora of Sumatra is very scanty including that of genusMarchantia (Marchantiaceae). This study was conducted to explore the diversity of Marchantia in Mount Sibayak North Sumatra, Indonesia. Altogether, seven species of Marchantia are found in Mount Sibayak North Sumatra, of which five are previously known (Marchantia acaulis , M. emarginata , M. geminata , M. paleacea , and M. treubii ), while one is as new species record (M. polymorpha ) for Sumatra, and one species has not been identified ( Marchantia sp. ). An identification key to the species of Marchantia from Sumatra is provided. Key words: Liverwort,Marchantia , Marchantiaceae, Mount Sibayak, North Sumatra INTRODUCTION Marchantia L. is one of the largest genera in the liverworts order Marchantiales. This genus is represented by 36 species found in the world (Bischler-Causse 1998). In Indonesia especially Sumatra, the floristic work onMarchantia is still very scarce. Herzog (1943) in his study of liverworts from Sumatra, recorded three species of Marchantia,namely M. emarginata , M. mucilaginosa and M.