Lö. Sipuncula: Developmental Evidence for Phylogenetic Inference

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RECORDS of the HAWAII BIOLOGICAL SURVEY for 1995 Part 2: Notes1

RECORDS OF THE HAWAII BIOLOGICAL SURVEY FOR 1995 Part 2: Notes1 This is the second of two parts to the Records of the Hawaii Biological Survey for 1995 and contains the notes on Hawaiian species of plants and animals including new state and island records, range extensions, and other information. Larger, more compre- hensive treatments and papers describing new taxa are treated in the first part of this Records [Bishop Museum Occasional Papers 45]. New Hawaiian Pest Plant Records for 1995 PATRICK CONANT (Hawaii Dept. of Agriculture, Plant Pest Control Branch, 1428 S King St, Honolulu, HI 96814) Fabaceae Ulex europaeus L. New island record On 6 October 1995, Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources, Division of Forestry and Wildlife employee C. Joao submitted an unusual plant he found while work- ing in the Molokai Forest Reserve. The plant was identified as U. europaeus and con- firmed by a Hawaii Department of Agriculture (HDOA) nox-A survey of the site on 9 October revealed an infestation of ca. 19 m2 at about 457 m elevation in the Kamiloa Distr., ca. 6.2 km above Kamehameha Highway. Distribution in Wagner et al. (1990, Manual of the flowering plants of Hawai‘i, p. 716) listed as Maui and Hawaii. Material examined: MOLOKAI: Molokai Forest Reserve, 4 Dec 1995, Guy Nagai s.n. (BISH). Melastomataceae Miconia calvescens DC. New island record, range extensions On 11 October, a student submitted a leaf specimen from the Wailua Houselots area on Kauai to PPC technician A. Bell, who had the specimen confirmed by David Lorence of the National Tropical Botanical Garden as being M. -

Number of Living Species in Australia and the World

Numbers of Living Species in Australia and the World 2nd edition Arthur D. Chapman Australian Biodiversity Information Services australia’s nature Toowoomba, Australia there is more still to be discovered… Report for the Australian Biological Resources Study Canberra, Australia September 2009 CONTENTS Foreword 1 Insecta (insects) 23 Plants 43 Viruses 59 Arachnida Magnoliophyta (flowering plants) 43 Protoctista (mainly Introduction 2 (spiders, scorpions, etc) 26 Gymnosperms (Coniferophyta, Protozoa—others included Executive Summary 6 Pycnogonida (sea spiders) 28 Cycadophyta, Gnetophyta under fungi, algae, Myriapoda and Ginkgophyta) 45 Chromista, etc) 60 Detailed discussion by Group 12 (millipedes, centipedes) 29 Ferns and Allies 46 Chordates 13 Acknowledgements 63 Crustacea (crabs, lobsters, etc) 31 Bryophyta Mammalia (mammals) 13 Onychophora (velvet worms) 32 (mosses, liverworts, hornworts) 47 References 66 Aves (birds) 14 Hexapoda (proturans, springtails) 33 Plant Algae (including green Reptilia (reptiles) 15 Mollusca (molluscs, shellfish) 34 algae, red algae, glaucophytes) 49 Amphibia (frogs, etc) 16 Annelida (segmented worms) 35 Fungi 51 Pisces (fishes including Nematoda Fungi (excluding taxa Chondrichthyes and (nematodes, roundworms) 36 treated under Chromista Osteichthyes) 17 and Protoctista) 51 Acanthocephala Agnatha (hagfish, (thorny-headed worms) 37 Lichen-forming fungi 53 lampreys, slime eels) 18 Platyhelminthes (flat worms) 38 Others 54 Cephalochordata (lancelets) 19 Cnidaria (jellyfish, Prokaryota (Bacteria Tunicata or Urochordata sea anenomes, corals) 39 [Monera] of previous report) 54 (sea squirts, doliolids, salps) 20 Porifera (sponges) 40 Cyanophyta (Cyanobacteria) 55 Invertebrates 21 Other Invertebrates 41 Chromista (including some Hemichordata (hemichordates) 21 species previously included Echinodermata (starfish, under either algae or fungi) 56 sea cucumbers, etc) 22 FOREWORD In Australia and around the world, biodiversity is under huge Harnessing core science and knowledge bases, like and growing pressure. -

Fauna of Australia 4A Phylum Sipuncula

FAUNA of AUSTRALIA Volume 4A POLYCHAETES & ALLIES The Southern Synthesis 5. PHYLUM SIPUNCULA STANLEY J. EDMONDS (Deceased 16 July 1995) © Commonwealth of Australia 2000. All material CC-BY unless otherwise stated. At night, Eunice Aphroditois emerges from its burrow to feed. Photo by Roger Steene DEFINITION AND GENERAL DESCRIPTION The Sipuncula is a group of soft-bodied, unsegmented, coelomate, worm-like marine invertebrates (Fig. 5.1; Pls 12.1–12.4). The body consists of a muscular trunk and an anteriorly placed, more slender introvert (Fig. 5.2), which bears the mouth at the anterior extremity of an introvert and a long, recurved, spirally wound alimentary canal lies within the spacious body cavity or coelom. The anus lies dorsally, usually on the anterior surface of the trunk near the base of the introvert. Tentacles either surround, or are associated with the mouth. Chaetae or bristles are absent. Two nephridia are present, occasionally only one. The nervous system, although unsegmented, is annelidan-like, consisting of a long ventral nerve cord and an anteriorly placed brain. The sexes are separate, fertilisation is external and cleavage of the zygote is spiral. The larva is a free-swimming trochophore. They are known commonly as peanut worms. AB D 40 mm 10 mm 5 mm C E 5 mm 5 mm Figure 5.1 External appearance of Australian sipunculans. A, SIPUNCULUS ROBUSTUS (Sipunculidae); B, GOLFINGIA VULGARIS HERDMANI (Golfingiidae); C, THEMISTE VARIOSPINOSA (Themistidae); D, PHASCOLOSOMA ANNULATUM (Phascolosomatidae); E, ASPIDOSIPHON LAEVIS (Aspidosiphonidae). (A, B, D, from Edmonds 1982; C, E, from Edmonds 1980) 2 Sipunculans live in burrows, tubes and protected places. -

An Annotated Checklist of the Marine Macroinvertebrates of Alaska David T

NOAA Professional Paper NMFS 19 An annotated checklist of the marine macroinvertebrates of Alaska David T. Drumm • Katherine P. Maslenikov Robert Van Syoc • James W. Orr • Robert R. Lauth Duane E. Stevenson • Theodore W. Pietsch November 2016 U.S. Department of Commerce NOAA Professional Penny Pritzker Secretary of Commerce National Oceanic Papers NMFS and Atmospheric Administration Kathryn D. Sullivan Scientific Editor* Administrator Richard Langton National Marine National Marine Fisheries Service Fisheries Service Northeast Fisheries Science Center Maine Field Station Eileen Sobeck 17 Godfrey Drive, Suite 1 Assistant Administrator Orono, Maine 04473 for Fisheries Associate Editor Kathryn Dennis National Marine Fisheries Service Office of Science and Technology Economics and Social Analysis Division 1845 Wasp Blvd., Bldg. 178 Honolulu, Hawaii 96818 Managing Editor Shelley Arenas National Marine Fisheries Service Scientific Publications Office 7600 Sand Point Way NE Seattle, Washington 98115 Editorial Committee Ann C. Matarese National Marine Fisheries Service James W. Orr National Marine Fisheries Service The NOAA Professional Paper NMFS (ISSN 1931-4590) series is pub- lished by the Scientific Publications Of- *Bruce Mundy (PIFSC) was Scientific Editor during the fice, National Marine Fisheries Service, scientific editing and preparation of this report. NOAA, 7600 Sand Point Way NE, Seattle, WA 98115. The Secretary of Commerce has The NOAA Professional Paper NMFS series carries peer-reviewed, lengthy original determined that the publication of research reports, taxonomic keys, species synopses, flora and fauna studies, and data- this series is necessary in the transac- intensive reports on investigations in fishery science, engineering, and economics. tion of the public business required by law of this Department. -

Madagascar and Indian Océan Sipuncula

Bull. Mus. natn. Hist. nat., Paris, 4e sér., 1, 1979, section A, n° 4 : 941-990. Madagascar and Indian Océan Sipuncula by Edward B. CUTLER and Norma J. CUTLER * Résumé. — Une collection de plus de 4 000 Sipunculides, représentant 54 espèces apparte- nant à 10 genres, est décrite. Les récoltes furent faites par de nombreux scientifiques fors de diverses campagnes océanographiques de 1960 à 1977. La plupart de ces récoltes proviennent de Madagas- car et des eaux environnantes ; quelques-unes ont été réalisées dans l'océan Pacifique Ouest et quelques autres dans des régions intermédiaires. Cinq nouvelles espèces sont décrites (Golfingia liochros, G. pectinatoida, Phascolion megaethi, Aspidosiphon thomassini et A. ochrus). Siphonosoma carolinense est mis en synonymie de 5. cumanense. Phascolion africanum est ramené à une sous- espèce de P. strombi. Des commentaires sont faits sur la morphologie de la plupart des espèces, et, surtout, des précisions nouvelles importantes sont faites pour Siphonosoma cumanense, Gol- fingia misakiana, G. rutilofusca, Aspidosiphon jukesii et Phascolosoma nigrescens. Des observations sur la répartition biogéographique des espèces sont données ; 10 espèces (6 Aspidosiphon, 2 Phas- colion, et 2 Themiste) provenant d'aires très différentes de celles d'où elles étaient connues anté- rieurement sont recensées. Abstract. — A collection ot over 4000 sipunculans representing 54 species in 10 gênera is described. The collections were made by numerous individuals and ships during the 1960's and early 1970's, most coming from Madagascar and surrounding waters ; a few from the western Pacific Océan ; and some from intervening régions. Five new species are described (Golfingia liochros, G. pectinatoida, Phascolion megaethi, Aspidosiphon thomassini, and A. -

Tropical Marine Invertebrates CAS BI 569 Phylum ANNELIDA by J

Tropical Marine Invertebrates CAS BI 569 Phylum ANNELIDA by J. R. Finnerty Phylum ANNELIDA Porifera Ctenophora Cnidaria Deuterostomia Ecdysozoa Lophotrochozoa Chordata Arthropoda Annelida Hemichordata Onychophora Mollusca Echinodermata Nematoda Platyhelminthes Acoelomorpha Silicispongiae Calcispongia PROTOSTOMIA “BILATERIA” (=TRIPLOBLASTICA) Bilateral symmetry (?) Mesoderm (triploblasty) Phylum ANNELIDA Porifera Ctenophora Cnidaria Deuterostomia Ecdysozoa Lophotrochozoa Chordata Arthropoda Annelida Hemichordata Onychophora Mollusca Echinodermata Nematoda Platyhelminthes Acoelomorpha Silicispongiae Calcispongia PROTOSTOMIA “COELOMATA” True coelom Coelomata gut cavity endoderm mesoderm coelom ectoderm [note: dorso-ventral inversion] Phylum ANNELIDA Porifera Ctenophora Cnidaria Deuterostomia Ecdysozoa Lophotrochozoa Chordata Arthropoda Annelida Hemichordata Onychophora Mollusca Echinodermata Nematoda Platyhelminthes Acoelomorpha Silicispongiae Calcispongia PROTOSTOMIA PROTOSTOMIA “first mouth” blastopore contributes to mouth ventral nerve cord The Blastopore ! Forms during gastrulation ectoderm blastocoel blastocoel endoderm gut blastoderm BLASTULA blastopore The Gut “internal, epithelium-lined cavity for the digestion and absorption of food sponges lack a gut simplest gut = blind sac (Cnidaria) blastopore gives rise to dual- function mouth/anus through-guts evolve later Protostome = blastopore contributes to the mouth Deuterostome = blastopore becomes the anus; mouth is a second opening Protostomy blastopore mouth anus Deuterostomy blastopore -

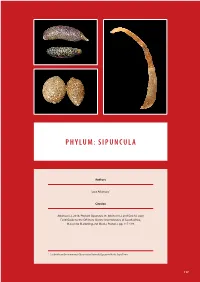

Phylum: Sipuncula

PHYLUM: SIPUNCULA Authors Lara Atkinson1 Citation Atkinson LJ. 2018. Phylum Sipuncula In: Atkinson LJ and Sink KJ (eds) Field Guide to the Ofshore Marine Invertebrates of South Africa, Malachite Marketing and Media, Pretoria, pp. 117-119. 1 South African Environmental Observation Network, Egagasini Node, Cape Town 117 Phylum: SIPUNCULA Peanut worms Peanut worms (Sipunculids) can be described as tentacles surrounding the mouth. Reproduction can smooth, unsegmented marine worms mostly be both sexual (external fertilisation) and asexual found buried in sediment due to their burrowing (transverse ission). habits. Some are known to burrow into solid rock or discarded shells, which are used as shelters. These Collection and preservation worms feed on detritus and sand as they burrow, Specimens should be preserved in 5% formalin processing the edible content. Sipunculid worms are and 96% ethanol for molecular studies. Menthol typically less than 10 cm in length, however some crystals can be used to relax the specimen for several have been known to reach several times that length. hours until unresponsive to touch. The specimen The body is divided into a trunk and introvert, the can then be kept in fresh water for one hour before latter being muscular and can be evaginated or preservation. retracted. The introvert terminates in a crown of References Cutler EB. 1994. The Sipuncula: Their systems, biology and evolution. Cornell University Press. New York. Huang D-Y, Chen J-Y, Vannier J and Saiz Salinas JI. 2004. Early Cambrian sipunculan worms from southwest China. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 271 (1549): 1671. doi:10.1098/ rspb.2004.2774. -

Musculature in Sipunculan Worms: Ontogeny and Ancestral States

EVOLUTION & DEVELOPMENT 11:1, 97–108 (2009) DOI: 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2008.00306.x Musculature in sipunculan worms: ontogeny and ancestral states Anja Schulzeà and Mary E. Rice Smithsonian Marine Station, 701 Seaway Drive, Fort Pierce, FL 34949, USA ÃAuthor for correspondence (email: [email protected]). Present address: Department of Marine Biology, Texas A & M University at Galveston, 5007 Avenue U, Galveston, TX 77551, USA. SUMMARY Molecular phylogenetics suggests that the introvert retractor muscles as adults, go through devel- Sipuncula fall into the Annelida, although they are mor- opmental stages with four retractor muscles that are phologically very distinct and lack segmentation. To under- eventually reduced to a lower number in the adult. The stand the evolutionary transformations from the annelid to the circular and sometimes the longitudinal body wall musculature sipunculan body plan, it is important to reconstruct the are split into bands that later transform into a smooth sheath. ancestral states within the respective clades at all life history Our ancestral state reconstructions suggest with nearly 100% stages. Here we reconstruct the ancestral states for the head/ probability that the ancestral sipunculan had four introvert introvert retractor muscles and the body wall musculature in retractor muscles, longitudinal body wall musculature in bands the Sipuncula using Bayesian statistics. In addition, we and circular body wall musculature arranged as a smooth describe the ontogenetic transformations of the two muscle sheath. Species with crawling larvae have more strongly systems in four sipunculan species with different de- developed body wall musculature than those with swimming velopmental modes, using F-actin staining with fluo- larvae. -

So. Calif. Marine Invertebrates SIPUNCULA by BRUCE

From; AHF Tech. Rpt. 3: So. Calif. Marine Invertebrates SIPUNCULA by BRUCE E. THOMPSON SCCWRP 646 W. P.C.H. Long Beach, CA 90806 The sipunculan fauna of southern California is poorly known. The first report was that of Chamberlain (1918). Fisher's (1950a,b, .1952) work provides the only major reference for this group. He erected subgenera for the genus Golfingia and described nearly all of the intertidal sipunculans, but only a few of the species from offshore. Recently however, several large scale surveys of the intertidal and benthic habitats of the entire southern California borderland have collected many species not reported from this area, including several apparently new taxa. This listing includes all previously reported sipunculans and also includes species seen in collections from southern California. It includes species from inter- tidal to bathyal habitats. The classification used is based upon the families of Stephen and Edmonds (1972), and the subgenera of Fisher (1952), as revised by Stephen and Edmonds (1972), Cutler and Murina (1977), and Cutler (1979). Sipuncula Stephen, 1965 Sipunculoidea Sedgwick, 1898 Sipunculida Pickford, 1947 Sipunculidae Baird, 1868 Siphonosoma Spengel, 1912 Siphonosoma (Siphonosoma) Fisher, 1950 Siphonosoma (Siphonosoma) ingens Fisher, 1950 Sipunculus Linnaeus, 1766 Sipuncvlus nudus Linnaeus, 1766 AHF Tech. Rpt. 3: So. Calif. Marine Invertebrates Golfingiidae Stephen & Edmonds, 1972 Golfingia Lankester, 1885 Golfingia (Apionsoma) Sluiter, 1902, sensu Cutler Golfingia (Apionsoma) capitata (Gerould, -

1409 Lab Manual

The Diversityof Life Lab Manual Stephen W. Ziser Department of Biology Pinnacle Campus for BIOL 1409 General Biology: The Diversity of Life Lab Activities, Homework & Lab Assignments 2017.6 Biol 1409: Diversity of Life – Lab Manual, Ziser, 2017.6 1 Biol 1409: Diversity of Life Ziser - Lab Manual Table of Contents 1. Overview of Semester Lab Activities Laboratory Activities . 3 2. Introduction to the Lab & Safety Information . 5 3. Laboratory Exercises Microscopy . 13 Taxonomy and Classification . 14 Cells – The Basic Units of Life . 18 Asexual & Sexual Reproduction . 23 Development & Life Cycles . 27 Ecosystems of Texas . 30 The Bacterial Kingdoms . 33 The Protists . 43 The Fungi . 51 The Plant Kingdom . 60 The Animal Kingdom . 90 4. Lab Reports (to be turned in - deadline dates as announced) Taxonomy & Classification . 16 Ecosystems of Texas. 31 The Bacterial Kingdoms . 40 The Protists . 47 The Fungi . 55 Leaf Identification Exercise . 69 The Plant Kingdom . 82 Identifying Common Freshwater Invertebrates . 105 The Animal Kingdom . 148 Biol 1409: Diversity of Life – Lab Manual, Ziser, 2017.6 2 Biol 1409: Diversity of Life Semester Activities Lab Exercises The schedule for the lab activities is posted in the Course Syllabus and on the instructor’s website. Changes will be announced ahead of time. The Photo Atlas is used as a visual guide to the activities described in this lab manual Introduction & Use of Compound Microscope & Dissecting Scope be able to identify and use the various parts of a compound microscope be able to use a magnifying -

Echinodermata

Echinodermata Gr : spine skin 6500 spp all marine except for few estuarine, none freshwater 1) pentamerous radial symmetry (adults) *larvae bilateral symmetrical 2) spines 3) endoskeleton mesodermally-derived ossicles calcareous plates up to 95% CaCO3, up to 15% MgCO3, salts, trace metals, small amount of organic materials 4) water vascular system (WVS) 5) tube feet (podia) Unicellular (acellular) Multicellular (metazoa) protozoan protists Poorly defined Diploblastic tissue layers Triploblastic Cnidaria Porifera Ctenophora Placozoa Uncertain Acoelomate Coelomate Pseudocoelomate Priapulida Rotifera Chaetognatha Platyhelminthes Nematoda Gastrotricha Rhynchocoela (Nemertea) Kinorhyncha Entoprocta Mesozoa Acanthocephala Loricifera Gnathostomulida Nematomorpha Protostomes Uncertain (misfits) Deuterostomes Annelida Mollusca Echinodermata Brachiopoda Hemichordata Arthropoda Phoronida Onychophora Bryozoa Chordata Pentastomida Pogonophora Sipuncula Echiura 1 Chapter 14: Echinodermata Classes: 1) Asteroidea (Gr: characterized by star-like) 1600 spp 2) Ophiuroidea (Gr: snake-tail-like) 2100 spp 3) Echinoidea (Gr: hedgehog-form) 1000 spp 4) Holothuroidea (Gr: sea cucumber-like) 1200 spp 5) Crinoidea (Gr: lily-like) stalked – 100 spp nonstalked, motile comatulid (feather stars)- 600 spp Asteroidea sea stars/starfish arms not sharply marked off from central star shaped disc spines fixed pedicellariae ambulacral groove open tube feet with suckers on oral side anus/madreporite aboral 2 Figure 22.01 Pincushion star, Culcita navaeguineae, preys on coral -

The Molecular and Developmental Biologisk Basis of Bodyplan Patterning in Institut Sipuncula and the Evolution Of

1 THE MOLECULAR AND DEVELOPMENTAL BIOLOGISK BASIS OF BODYPLAN PATTERNING IN INSTITUT SIPUNCULA AND THE EVOLUTION OF SEGMENTATION Alen Kristof | Københavns Universitet 2 DEPARTMENT OF BIOLOGY FACULTY OF SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF COPENHAGEN PhD thesis Alen Kristof The molecular and developmental basis of bodyplan patterning in Sipuncula and the evolution of segmentation Principal supervisor Associate Prof. Dr. Andreas Wanninger Co-supervisor Prof. Dr. Pedro Martinez, University of Barcelona April, 2011 3 Reviewed by: Assistant Professor Anja Schulze Department of Marine Biology, Texas A&M University at Galveston Galveston, USA Professor Stefan Richter Department of Biological Sciences, University of Rostock Rostock, Germany Faculty opponent: Associate Professor Danny Eibye-Jacobsen Natural History Museum of Denmark, University of Denmark Copenhagen, Denmark ______________________________________________________________ Cover illustration: Front: Frontal view of an adult specimen of the sipunculan Themiste pyroides with a total length of 13 cm. Back: Confocal laserscanning micrograph of a Phascolosoma agassizii pelagosphera larva showing its musculature. Lateral view. Age of the specimen is 15 days and its total size approximately 300 µm in length. 4 “In a world that keeps on pushin’ me around, but I’ll stand my ground, and I won’t back down.” Thomas Earl Petty, 1989 5 Preface Preface The content of this dissertation comprises three years of research at the University of Copenhagen from May 1, 2008 to April 30, 2011. The PhD project on the development of Sipuncula was mainly carried out in the Research Group for Comparative Zoology, Department of Biology, University of Copenhagen under the supervision of Assoc. Prof. Dr. Andreas Wanninger. I spent nine months working on body patterning genes in the lab of Prof.