The Molecular and Developmental Biologisk Basis of Bodyplan Patterning in Institut Sipuncula and the Evolution Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RECORDS of the HAWAII BIOLOGICAL SURVEY for 1995 Part 2: Notes1

RECORDS OF THE HAWAII BIOLOGICAL SURVEY FOR 1995 Part 2: Notes1 This is the second of two parts to the Records of the Hawaii Biological Survey for 1995 and contains the notes on Hawaiian species of plants and animals including new state and island records, range extensions, and other information. Larger, more compre- hensive treatments and papers describing new taxa are treated in the first part of this Records [Bishop Museum Occasional Papers 45]. New Hawaiian Pest Plant Records for 1995 PATRICK CONANT (Hawaii Dept. of Agriculture, Plant Pest Control Branch, 1428 S King St, Honolulu, HI 96814) Fabaceae Ulex europaeus L. New island record On 6 October 1995, Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources, Division of Forestry and Wildlife employee C. Joao submitted an unusual plant he found while work- ing in the Molokai Forest Reserve. The plant was identified as U. europaeus and con- firmed by a Hawaii Department of Agriculture (HDOA) nox-A survey of the site on 9 October revealed an infestation of ca. 19 m2 at about 457 m elevation in the Kamiloa Distr., ca. 6.2 km above Kamehameha Highway. Distribution in Wagner et al. (1990, Manual of the flowering plants of Hawai‘i, p. 716) listed as Maui and Hawaii. Material examined: MOLOKAI: Molokai Forest Reserve, 4 Dec 1995, Guy Nagai s.n. (BISH). Melastomataceae Miconia calvescens DC. New island record, range extensions On 11 October, a student submitted a leaf specimen from the Wailua Houselots area on Kauai to PPC technician A. Bell, who had the specimen confirmed by David Lorence of the National Tropical Botanical Garden as being M. -

Number of Living Species in Australia and the World

Numbers of Living Species in Australia and the World 2nd edition Arthur D. Chapman Australian Biodiversity Information Services australia’s nature Toowoomba, Australia there is more still to be discovered… Report for the Australian Biological Resources Study Canberra, Australia September 2009 CONTENTS Foreword 1 Insecta (insects) 23 Plants 43 Viruses 59 Arachnida Magnoliophyta (flowering plants) 43 Protoctista (mainly Introduction 2 (spiders, scorpions, etc) 26 Gymnosperms (Coniferophyta, Protozoa—others included Executive Summary 6 Pycnogonida (sea spiders) 28 Cycadophyta, Gnetophyta under fungi, algae, Myriapoda and Ginkgophyta) 45 Chromista, etc) 60 Detailed discussion by Group 12 (millipedes, centipedes) 29 Ferns and Allies 46 Chordates 13 Acknowledgements 63 Crustacea (crabs, lobsters, etc) 31 Bryophyta Mammalia (mammals) 13 Onychophora (velvet worms) 32 (mosses, liverworts, hornworts) 47 References 66 Aves (birds) 14 Hexapoda (proturans, springtails) 33 Plant Algae (including green Reptilia (reptiles) 15 Mollusca (molluscs, shellfish) 34 algae, red algae, glaucophytes) 49 Amphibia (frogs, etc) 16 Annelida (segmented worms) 35 Fungi 51 Pisces (fishes including Nematoda Fungi (excluding taxa Chondrichthyes and (nematodes, roundworms) 36 treated under Chromista Osteichthyes) 17 and Protoctista) 51 Acanthocephala Agnatha (hagfish, (thorny-headed worms) 37 Lichen-forming fungi 53 lampreys, slime eels) 18 Platyhelminthes (flat worms) 38 Others 54 Cephalochordata (lancelets) 19 Cnidaria (jellyfish, Prokaryota (Bacteria Tunicata or Urochordata sea anenomes, corals) 39 [Monera] of previous report) 54 (sea squirts, doliolids, salps) 20 Porifera (sponges) 40 Cyanophyta (Cyanobacteria) 55 Invertebrates 21 Other Invertebrates 41 Chromista (including some Hemichordata (hemichordates) 21 species previously included Echinodermata (starfish, under either algae or fungi) 56 sea cucumbers, etc) 22 FOREWORD In Australia and around the world, biodiversity is under huge Harnessing core science and knowledge bases, like and growing pressure. -

Comparative Neuroanatomy of Mollusks and Nemerteans in the Context of Deep Metazoan Phylogeny

Comparative Neuroanatomy of Mollusks and Nemerteans in the Context of Deep Metazoan Phylogeny Von der Fakultät für Mathematik, Informatik und Naturwissenschaften der RWTH Aachen University zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades einer Doktorin der Naturwissenschaften genehmigte Dissertation vorgelegt von Diplom-Biologin Simone Faller aus Frankfurt am Main Berichter: Privatdozent Dr. Rudolf Loesel Universitätsprofessor Dr. Peter Bräunig Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 09. März 2012 Diese Dissertation ist auf den Internetseiten der Hochschulbibliothek online verfügbar. Contents 1 General Introduction 1 Deep Metazoan Phylogeny 1 Neurophylogeny 2 Mollusca 5 Nemertea 6 Aim of the thesis 7 2 Neuroanatomy of Minor Mollusca 9 Introduction 9 Material and Methods 10 Results 12 Caudofoveata 12 Scutopus ventrolineatus 12 Falcidens crossotus 16 Solenogastres 16 Dorymenia sarsii 16 Polyplacophora 20 Lepidochitona cinerea 20 Acanthochitona crinita 20 Scaphopoda 22 Antalis entalis 22 Entalina quinquangularis 24 Discussion 25 Structure of the brain and nerve cords 25 Caudofoveata 25 Solenogastres 26 Polyplacophora 27 Scaphopoda 27 i CONTENTS Evolutionary considerations 28 Relationship among non-conchiferan molluscan taxa 28 Position of the Scaphopoda within Conchifera 29 Position of Mollusca within Protostomia 30 3 Neuroanatomy of Nemertea 33 Introduction 33 Material and Methods 34 Results 35 Brain 35 Cerebral organ 38 Nerve cords and peripheral nervous system 38 Discussion 38 Peripheral nervous system 40 Central nervous system 40 In search for the urbilaterian brain 42 4 General Discussion 45 Evolution of higher brain centers 46 Neuroanatomical glossary and data matrix – Essential steps toward a cladistic analysis of neuroanatomical data 49 5 Summary 53 6 Zusammenfassung 57 7 References 61 Danksagung 75 Lebenslauf 79 ii iii 1 General Introduction Deep Metazoan Phylogeny The concept of phylogeny follows directly from the theory of evolution as published by Charles Darwin in The origin of species (1859). -

Defining Phyla: Evolutionary Pathways to Metazoan Body Plans

EVOLUTION & DEVELOPMENT 3:6, 432-442 (2001) Defining phyla: evolutionary pathways to metazoan body plans Allen G. Collins^ and James W. Valentine* Museum of Paleontology and Department of Integrative Biology, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA 'Author for correspondence (email: [email protected]) 'Present address: Section of Ecology, Befiavior, and Evolution, Division of Biology, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093-0116, USA SUMMARY Phyla are defined by two sets of criteria, one pothesis of Nielsen; the clonal hypothesis of Dewel; the set- morphological and the other historical. Molecular evidence aside cell hypothesis of Davidson et al.; and a benthic hy- permits the grouping of animals into clades and suggests that pothesis suggested by the fossil record. It is concluded that a some groups widely recognized as phyla are paraphyletic, benthic radiation of animals could have supplied the ances- while some may be polyphyletic; the phyletic status of crown tral lineages of all but a few phyla, is consistent with molecu- phyla is tabulated. Four recent evolutionary scenarios for the lar evidence, accords well with fossil evidence, and accounts origins of metazoan phyla and of supraphyletic clades are as- for some of the difficulties in phylogenetic analyses of phyla sessed in the light of a molecular phylogeny: the trochaea hy- based on morphological criteria. INTRODUCTION Molecules have provided an important operational ad- vance to addressing questions about the origins of animal Concepts of animal phyla have changed importantly from phyla. Molecular developmental and comparative genomic their origins in the six Linnaean classis and four Cuvieran evidence offer insights into the genetic bases of body plan embranchements. -

Sipuncula: an Emerging Model of Spiralian Development and Evolution MICHAEL J

Int. J. Dev. Biol. 58: 485-499 (2014) doi: 10.1387/ijdb.140095mb www.intjdevbiol.com Sipuncula: an emerging model of spiralian development and evolution MICHAEL J. BOYLE1 and MARY E. RICE2 1Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI), Panama, Republic of Panama and 2Smithsonian Marine Station at Fort Pierce (SMSFP), Florida, USA ABSTRACT Sipuncula is an ancient clade of unsegmented marine worms that develop through a conserved pattern of unequal quartet spiral cleavage. They exhibit putative character modifications, including conspicuously large first-quartet micromeres and prototroch cells, postoral metatroch with exclusive locomotory function, paired retractor muscles and terminal organ system, and a U-shaped digestive architecture with left-right asymmetric development. Four developmental life history patterns are recognized, and they have evolved a unique metazoan larval type, the pelagosphera. When compared with other quartet spiral-cleaving models, sipunculan development is understud- ied, challenging and typically absent from evolutionary interpretations of spiralian larval and adult body plan diversity. If spiral cleavage is appropriately viewed as a flexible character complex, then understudied clades and characters should be investigated. We are pursuing sipunculan models for modern molecular, genetic and cellular research on evolution of spiralian development. Protocols for whole mount gene expression studies are established in four species. Molecular labeling and confocal imaging techniques are operative from embryogenesis through larval development. Next- generation sequencing of developmental transcriptomes has been completed for two species with highly contrasting life history patterns, Phascolion cryptum (direct development) and Nephasoma pellucidum (indirect planktotrophy). Looking forward, we will attempt intracellular lineage tracing and fate-mapping studies in a proposed model sipunculan, Themiste lageniformis. -

Fauna of Australia 4A Phylum Sipuncula

FAUNA of AUSTRALIA Volume 4A POLYCHAETES & ALLIES The Southern Synthesis 5. PHYLUM SIPUNCULA STANLEY J. EDMONDS (Deceased 16 July 1995) © Commonwealth of Australia 2000. All material CC-BY unless otherwise stated. At night, Eunice Aphroditois emerges from its burrow to feed. Photo by Roger Steene DEFINITION AND GENERAL DESCRIPTION The Sipuncula is a group of soft-bodied, unsegmented, coelomate, worm-like marine invertebrates (Fig. 5.1; Pls 12.1–12.4). The body consists of a muscular trunk and an anteriorly placed, more slender introvert (Fig. 5.2), which bears the mouth at the anterior extremity of an introvert and a long, recurved, spirally wound alimentary canal lies within the spacious body cavity or coelom. The anus lies dorsally, usually on the anterior surface of the trunk near the base of the introvert. Tentacles either surround, or are associated with the mouth. Chaetae or bristles are absent. Two nephridia are present, occasionally only one. The nervous system, although unsegmented, is annelidan-like, consisting of a long ventral nerve cord and an anteriorly placed brain. The sexes are separate, fertilisation is external and cleavage of the zygote is spiral. The larva is a free-swimming trochophore. They are known commonly as peanut worms. AB D 40 mm 10 mm 5 mm C E 5 mm 5 mm Figure 5.1 External appearance of Australian sipunculans. A, SIPUNCULUS ROBUSTUS (Sipunculidae); B, GOLFINGIA VULGARIS HERDMANI (Golfingiidae); C, THEMISTE VARIOSPINOSA (Themistidae); D, PHASCOLOSOMA ANNULATUM (Phascolosomatidae); E, ASPIDOSIPHON LAEVIS (Aspidosiphonidae). (A, B, D, from Edmonds 1982; C, E, from Edmonds 1980) 2 Sipunculans live in burrows, tubes and protected places. -

10. Sipuncula

10. SIPUNCULA MARY E. RICE Smithsonian Marine Station at Link Port, 5612 Old Dixie Highway, Fort Pierce, Florida 34946, U.S.A. JOHN F. PILGER Department of Biology, Agnes Scott College, Decatur, Georgia 30030, U.S.A. I. INTRODUCTION Studies of development in sipunculans were first published in the latter part of the 19th century, but it has been only recently that reproductive cycles have been investigated and that sufficient comparative information has become available for any understanding of the trends and diversity of developmental patterns. In addition to their more usual means of sexual reproduction, a few sipunculans have been found to use different modes of asexual reproduction. Processes of transverse fission and budding have been described by Rajulu and Krishnan (1969), Rice (1970), and Rajulu (1975). Also, an interesting example of parthenogenesis has been discovered and is under current study (Pilger, 1987, 1989). A number of descriptive studies have been made on breeding cycles of sipun- culans; however, there have been no interpretive analyses or experimental consider- ations of controlling mechanisms. In connection with these studies a few incidental observations have been reported on fecundity. Major references on reproductive cycles are those of Gonse (1956a, b). Rice (1975a), and Gibbs (1975, 1976). II. ASEXUAL PROPAGATION AND REGENERATION Although sexual reproduction is the common mode of propagation among sipuncu- lans, asexual reproduction has been reported to occur in two species, Aspidosiphon brocki and Sipunculus robustus (Rice, 1970 and Rajulu and Krishnan, 1969 re- spectively). In the former it occurs as a type of transverse fission and in the latter as either budding or transverse fission. -

Tropical Marine Invertebrates CAS BI 569 Phylum ANNELIDA by J

Tropical Marine Invertebrates CAS BI 569 Phylum ANNELIDA by J. R. Finnerty Phylum ANNELIDA Porifera Ctenophora Cnidaria Deuterostomia Ecdysozoa Lophotrochozoa Chordata Arthropoda Annelida Hemichordata Onychophora Mollusca Echinodermata Nematoda Platyhelminthes Acoelomorpha Silicispongiae Calcispongia PROTOSTOMIA “BILATERIA” (=TRIPLOBLASTICA) Bilateral symmetry (?) Mesoderm (triploblasty) Phylum ANNELIDA Porifera Ctenophora Cnidaria Deuterostomia Ecdysozoa Lophotrochozoa Chordata Arthropoda Annelida Hemichordata Onychophora Mollusca Echinodermata Nematoda Platyhelminthes Acoelomorpha Silicispongiae Calcispongia PROTOSTOMIA “COELOMATA” True coelom Coelomata gut cavity endoderm mesoderm coelom ectoderm [note: dorso-ventral inversion] Phylum ANNELIDA Porifera Ctenophora Cnidaria Deuterostomia Ecdysozoa Lophotrochozoa Chordata Arthropoda Annelida Hemichordata Onychophora Mollusca Echinodermata Nematoda Platyhelminthes Acoelomorpha Silicispongiae Calcispongia PROTOSTOMIA PROTOSTOMIA “first mouth” blastopore contributes to mouth ventral nerve cord The Blastopore ! Forms during gastrulation ectoderm blastocoel blastocoel endoderm gut blastoderm BLASTULA blastopore The Gut “internal, epithelium-lined cavity for the digestion and absorption of food sponges lack a gut simplest gut = blind sac (Cnidaria) blastopore gives rise to dual- function mouth/anus through-guts evolve later Protostome = blastopore contributes to the mouth Deuterostome = blastopore becomes the anus; mouth is a second opening Protostomy blastopore mouth anus Deuterostomy blastopore -

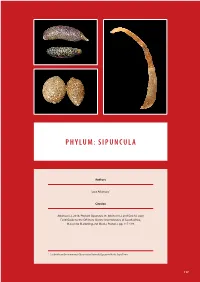

Phylum: Sipuncula

PHYLUM: SIPUNCULA Authors Lara Atkinson1 Citation Atkinson LJ. 2018. Phylum Sipuncula In: Atkinson LJ and Sink KJ (eds) Field Guide to the Ofshore Marine Invertebrates of South Africa, Malachite Marketing and Media, Pretoria, pp. 117-119. 1 South African Environmental Observation Network, Egagasini Node, Cape Town 117 Phylum: SIPUNCULA Peanut worms Peanut worms (Sipunculids) can be described as tentacles surrounding the mouth. Reproduction can smooth, unsegmented marine worms mostly be both sexual (external fertilisation) and asexual found buried in sediment due to their burrowing (transverse ission). habits. Some are known to burrow into solid rock or discarded shells, which are used as shelters. These Collection and preservation worms feed on detritus and sand as they burrow, Specimens should be preserved in 5% formalin processing the edible content. Sipunculid worms are and 96% ethanol for molecular studies. Menthol typically less than 10 cm in length, however some crystals can be used to relax the specimen for several have been known to reach several times that length. hours until unresponsive to touch. The specimen The body is divided into a trunk and introvert, the can then be kept in fresh water for one hour before latter being muscular and can be evaginated or preservation. retracted. The introvert terminates in a crown of References Cutler EB. 1994. The Sipuncula: Their systems, biology and evolution. Cornell University Press. New York. Huang D-Y, Chen J-Y, Vannier J and Saiz Salinas JI. 2004. Early Cambrian sipunculan worms from southwest China. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 271 (1549): 1671. doi:10.1098/ rspb.2004.2774. -

Animal Phylogeny and the Ancestry of Bilaterians: Inferences from Morphology and 18S Rdna Gene Sequences

EVOLUTION & DEVELOPMENT 3:3, 170–205 (2001) Animal phylogeny and the ancestry of bilaterians: inferences from morphology and 18S rDNA gene sequences Kevin J. Peterson and Douglas J. Eernisse* Department of Biological Sciences, Dartmouth College, Hanover NH 03755, USA; and *Department of Biological Science, California State University, Fullerton CA 92834-6850, USA *Author for correspondence (email: [email protected]) SUMMARY Insight into the origin and early evolution of the and protostomes, with ctenophores the bilaterian sister- animal phyla requires an understanding of how animal group, whereas 18S rDNA suggests that the root is within the groups are related to one another. Thus, we set out to explore Lophotrochozoa with acoel flatworms and gnathostomulids animal phylogeny by analyzing with maximum parsimony 138 as basal bilaterians, and with cnidarians the bilaterian sister- morphological characters from 40 metazoan groups, and 304 group. We suggest that this basal position of acoels and gna- 18S rDNA sequences, both separately and together. Both thostomulids is artifactal because for 1000 replicate phyloge- types of data agree that arthropods are not closely related to netic analyses with one random sequence as outgroup, the annelids: the former group with nematodes and other molting majority root with an acoel flatworm or gnathostomulid as the animals (Ecdysozoa), and the latter group with molluscs and basal ingroup lineage. When these problematic taxa are elim- other taxa with spiral cleavage. Furthermore, neither brachi- inated from the matrix, the combined analysis suggests that opods nor chaetognaths group with deuterostomes; brachiopods the root lies between the deuterostomes and protostomes, are allied with the molluscs and annelids (Lophotrochozoa), and Ctenophora is the bilaterian sister-group. -

So. Calif. Marine Invertebrates SIPUNCULA by BRUCE

From; AHF Tech. Rpt. 3: So. Calif. Marine Invertebrates SIPUNCULA by BRUCE E. THOMPSON SCCWRP 646 W. P.C.H. Long Beach, CA 90806 The sipunculan fauna of southern California is poorly known. The first report was that of Chamberlain (1918). Fisher's (1950a,b, .1952) work provides the only major reference for this group. He erected subgenera for the genus Golfingia and described nearly all of the intertidal sipunculans, but only a few of the species from offshore. Recently however, several large scale surveys of the intertidal and benthic habitats of the entire southern California borderland have collected many species not reported from this area, including several apparently new taxa. This listing includes all previously reported sipunculans and also includes species seen in collections from southern California. It includes species from inter- tidal to bathyal habitats. The classification used is based upon the families of Stephen and Edmonds (1972), and the subgenera of Fisher (1952), as revised by Stephen and Edmonds (1972), Cutler and Murina (1977), and Cutler (1979). Sipuncula Stephen, 1965 Sipunculoidea Sedgwick, 1898 Sipunculida Pickford, 1947 Sipunculidae Baird, 1868 Siphonosoma Spengel, 1912 Siphonosoma (Siphonosoma) Fisher, 1950 Siphonosoma (Siphonosoma) ingens Fisher, 1950 Sipunculus Linnaeus, 1766 Sipuncvlus nudus Linnaeus, 1766 AHF Tech. Rpt. 3: So. Calif. Marine Invertebrates Golfingiidae Stephen & Edmonds, 1972 Golfingia Lankester, 1885 Golfingia (Apionsoma) Sluiter, 1902, sensu Cutler Golfingia (Apionsoma) capitata (Gerould, -

Nemertean and Phoronid Genomes Reveal Lophotrochozoan Evolution and the Origin of Bilaterian Heads

Nemertean and phoronid genomes reveal lophotrochozoan evolution and the origin of bilaterian heads Author Yi-Jyun Luo, Miyuki Kanda, Ryo Koyanagi, Kanako Hisata, Tadashi Akiyama, Hirotaka Sakamoto, Tatsuya Sakamoto, Noriyuki Satoh journal or Nature Ecology & Evolution publication title volume 2 page range 141-151 year 2017-12-04 Publisher Springer Nature Macmillan Publishers Limited Rights (C) 2017 Macmillan Publishers Limited, part of Springer Nature. Author's flag publisher URL http://id.nii.ac.jp/1394/00000281/ doi: info:doi/10.1038/s41559-017-0389-y Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) ARTICLES https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-017-0389-y Nemertean and phoronid genomes reveal lophotrochozoan evolution and the origin of bilaterian heads Yi-Jyun Luo 1,4*, Miyuki Kanda2, Ryo Koyanagi2, Kanako Hisata1, Tadashi Akiyama3, Hirotaka Sakamoto3, Tatsuya Sakamoto3 and Noriyuki Satoh 1* Nemerteans (ribbon worms) and phoronids (horseshoe worms) are closely related lophotrochozoans—a group of animals including leeches, snails and other invertebrates. Lophotrochozoans represent a superphylum that is crucial to our understand- ing of bilaterian evolution. However, given the inconsistency of molecular and morphological data for these groups, their ori- gins have been unclear. Here, we present draft genomes of the nemertean Notospermus geniculatus and the phoronid Phoronis australis, together with transcriptomes along the adult bodies. Our genome-based phylogenetic analyses place Nemertea sis- ter to the group containing Phoronida and Brachiopoda. We show that lophotrochozoans share many gene families with deu- terostomes, suggesting that these two groups retain a core bilaterian gene repertoire that ecdysozoans (for example, flies and nematodes) and platyzoans (for example, flatworms and rotifers) do not.