Downloaded from Brill.Com10/04/2021 11:07:43PM Via Free Access P a G E | 156

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Truth About Angels

PROJECT CONNECT PROJECT CONNECT PROJECT CONNECT The Truth About Angels by Donald L. Deffner I grew up during the Great Depression in the early 1930s. My father was a minister. Behind our small home was a dirt alley which led nine blocks to downtown Wichita, Kansas. I can remember when I was a boy the hungry, destitute men who came to the back door begging for food. My mother never turned them down. She shared what little we had, even if only a couple of pieces of bread and a glass of milk. My mother didn’t just say, “Depart in peace! I’ll pray for you! Keep warm and well fed!” (See James 2:16.) No. She acted. She gave. Often I was curious about these mysterious and somewhat scary men. I had a sense that they were “different” than I was, not worse, not better, just different. I always watched these strangers heading back up the alley toward downtown, and sometimes, in a cops-and-robbers fashion, I secretly followed them, jumping behind bushes so I wouldn’t be seen. I think I half expected them to suddenly disappear. After all, my Sunday school teacher, encouraging us to be kind and care for strangers, told us the Bible says that, by doing so, many people have entertained angels without knowing it (see Hebrews 13:2). I never saw any of the men disappear. They were ordinary, hungry human beings. But my Sunday school teacher was right. God does send His angels to us, and they do interact with us—not just to test us and see if we are kind, but to protect us and guide us. -

HIGHLANDS NEWS-SUN Thursday, October 31, 2019

HIGHLANDS NEWS-SUN Thursday, October 31, 2019 VOL. 100 | NO. 304 | $1.00 YOUR HOMETOWN NEWSPAPER SINCE 1919 An Edition Of The Sun Markley charged Bear breaks school rules with child By ROBERT MILLER area of South Orange Street NEWS CLERK and Nasturtium Avenue, one block off East Center Street, in neglect after SEBRING — Students and the area between First United faculty at Sebring Middle Methodist Church and the daughter dies School found themselves Sebring Parkway. on the lookout for a bear Sebring Police Commander By KIM LEATHERMAN Wednesday afternoon just as Curtis Hart said that Sebring STAFF WRITER the end-of-day school bell residents had a bear sighting rang. off Hammock Road a few AVON PARK — Elizabeth Danielle A bear was spotted in the years ago and police have had Markley, 29, of Avon Park was arrested area between the school periodic reports of them since. Tuesday afternoon by the and the Highlands County But not immediately down- Highlands County Sheriff’s Sheriff’s Office. Florida Fish town. “This is the first time Office. She is being charged and Wildlife officials would in recent memory that a bear with child neglect with not allow students to leave the had been this close to down- HCSO SCREENSHOT great bodily harm. The campus on foot or via bicycle town Sebring,” Hart said. “The young girl died on Feb. 27. while they looked for the bear. BEAR | 7A The bear caught on security camera near Fernleaf Avenue on An intensive investiga- The bear was seen in the Tuesday evening. tion revealed Markley’s 9-year-old daughter did not MARKLEY get the medical care she needed and died of “pneu- monia with Contributing Conditions of congenital heart disease, fluid and electrolyte imbalance.” The investigation results were provided by District Six Chief Medical Examiner Dr. -

Indigo in Motion …A Decidedly Unique Fusion of Jazz and Ballet

A Teacher's Handbook for Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre's Production of Indigo in Motion …a decidedly unique fusion of jazz and ballet Choreography Kevin O'Day Lynne Taylor-Corbett Dwight Rhoden Music Ray Brown Stanley Turrentine Lena Horne Billy Strayhorn Sponsored by Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre's Arts Education programs are supported by major grants from the following: Allegheny Regional Asset District Claude Worthington Benedum Foundation Pennsylvania Council on the Arts The Hearst Foundation Sponsoring the William Randolph Hearst Endowed Fund for Arts Education Additional support is provided by: Alcoa Foundation, Allegheny County, Bayer Foundation, H. M. Bitner Charitable Trust, Columbia Gas of Pennsylvania, Dominion, Duquesne Light Company, Frick Fund of the Buhl Foundation, Grable Foundation, Highmark Blue Cross Blue Shield, The Mary Hillman Jennings Foundation, Milton G. Hulme Charitable Foundation, The Roy A. Hunt Foundation, Earl Knudsen Charitable Foundation, Lazarus Fund of the Federated Foundation, Matthews Educational and Charitable Foundation,, McFeely-Rogers Fund of The Pittsburgh Foundation, William V. and Catherine A. McKinney Charitable Foundation, Howard and Nell E. Miller Foundation, The Charles M. Morris Charitable Trust, Pennsylvania Department of Community and Economic Development, The Rockwell Foundation, James M. and Lucy K. Schoonmaker Foundation, Target Corporation, Robert and Mary Weisbrod Foundation, and the Hilda M. Willis Foundation. INTRODUCTION Dear Educator, In the social atmosphere of our country, in this generation, a professional ballet company with dedicated and highly trained artists cannot afford to be just a vehicle for public entertainment. We have a mission, a commission, and an obligation to be the standard bearer for this beautiful classical art so that generations to come can view, enjoy, and appreciate the significance that culture has in our lives. -

Supernatural Bingo

B I N G O Sam and Dean’s Flashbacks are Sam suffers Castiel and Meg Meg returns new home ‘The seen more ‘Trial’ have a special with vital Batcave’ is in symptoms moment information the episode together Garth and or Crowley spouts Dean uncovers Meg does not Castiel gets into Kevin is off his usual some special fare well in their Deans face referenced wisecracks and reading material mission or insults from the bunker Angel killing Brothers go Black eyes and Castiel manages sword is used undercover or smoke is to free himself seen from Naomi’s mind control Lucifer is Castiel flies in Naomi messes Ruby’s knife and A secret is referenced un-expectantly with Castiels or Demon revealed head and forces bombs are used him to do nasty deeds The Demon and Heaven VS Hell! Reference to the Devils Trap is Big betrayal or Angel Castiel and Trials is made used occurs tablet(s) are Crowley get into referenced a confrontation B I N G O Reference to The Demon and Big betrayal Heaven VS Hell! Devils Trap is the Trials is or Angel occurs Castiel and used made tablet(s) are Crowley get into referenced a confrontation Castiel flies in Naomi messes Lucifer is A secret is Ruby’s knife and un-expectantly with Castiels referenced revealed or Demon head and forces bombs are used him to do nasty deeds Brothers go Black eyes and Castiel manages Sam suffers undercover or smoke is to free himself more ‘Trial’ seen from Naomi’s symptoms mind control Meg returns Castiel and Meg Angel killing Sam and Dean’s Flashbacks are with vital have a special sword is used new home -

De-Demonising the Old Testament

De-Demonising the Old Testament An Investigation of Azazel , Lilith , Deber , Qeteb and Reshef in the Hebrew Bible Judit M. Blair Doctor of Philosophy University of Edinburgh 2008 Declaration I declare that the present thesis has been composed by me, that it represents my own research, and that it has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. ______________________ Judit M. Blair ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are many people to thank and acknowledge for their support and help over the past years. Firstly I would like to thank the School of Divinity for the scholarship and the opportunity they provided me in being able to do this PhD. I would like to thank my ‘numerous’ supervisors who have given of their time, energy and knowledge in making this thesis possible: To Professor Hans Barstad for his patience, advice and guiding hand, in particular for his ‘adopting’ me as his own. For his understanding and help with German I am most grateful. To Dr Peter Hayman for giving of his own time to help me in learning Hebrew, then accepting me to study for a PhD, and in particular for his attention to detail. To Professor Nick Wyatt who supervised my Masters and PhD before his retirement for his advice and support. I would also like to thank the staff at New College Library for their assistance at all times, and Dr Jessie Paterson and Bronwen Currie for computer support. My fellow colleagues have provided feedback and helpful criticism and I would especially like to thank all members of HOTS-lite I have known over the years. -

Will This Manhattan Projects Original Artwork Cliffhanger Make Another

COMICS COSPLAY TV/FILM GAMES SUBMIT CGC Search … Will This Manhattan Projects Original Artwork Cliffhanger Make Another Big Splash? Posted by Mark Seifert March 19, 2014 0 Comments Facebook Twitter Pinterest LinkedIn Tumblr Email Reddit [The Manhattan Projects #18 has been out for a couple weeks, but still — if you haven’t read this issue and plan to, you might want to skip this post for now.] Several years into the digital era for both comics reading and comics production, I still love to look at original comic art up close. The look and feel of the art board, the subtle texture of the ink, the faint traces of changes and corrections… it all adds up to a little extra insight into the time and circumstances behind the comics book’s creation. We’ve mentioned a bunch of noteworthy original art sales here in recent times — from that awe-inspiring Golden Age Action Comics #15 cover by Fred Guardineer, to this Silver Age Fantastic Four #55 page by Jack Kirby, to this Bronze Age classic Amazing Spider- Man #121 cover by John Romita Sr, down to the current record holder for a piece of American comic book art with this Amazing Spider-Man #328 cover by Todd McFarlane. And increasingly, original art sales from much more recent comics are turning heads as well. It’s probably no surprise that Skottie Young original art is highly sought after, or that Walking Dead original art — even panel pages — can command some eye- popping prices. But modern comic art collectors have broadened their interests to many other artists and titles of quality in recent times, such as this Pia Guerra Y: The Last Man panel page that recently went for $1000. -

Episode 47 – “A Very Merry Supernatural Christmas”

Episode 47 – “A Very Merry Supernatural Christmas” Release Date: December 24, 2018 Running Time: 1 hour, 11 minutes Sally: Kay. Fuck, marry, kill. Sam, Dean, Cas. Emily: Ah, fu-- (laugh) Brie: I feel like that’s easy. (laugh) Emily: That’s super easy. Sally: I just -- we gotta start the episode somehow. Emily: OK, kill Sam, obviously. Brie: Duh. Yeah, no, duh. Yeah. Emily: Yeah. Brie: Yeah. Mm. Sally: (laugh) Emily: Uh, then I guess I’d marry Cas? Brie: Yeah … Sally: Fuck Dean? Emily: Yeah. Sally: That’s where I was sitting too. Brie: Yeah. Sally: So we’re all in agreement. Brie: Yeah. Emily: I just -- Cas actually has a personality I can stand. When he actually develops a personality, which is later, I guess, in the series. Sally: Yeah. Brie: I do think, though, that, like, the emotional parts of Dean -- Emily: Yeah. Brie: If that -- if that was, like, turned on all the time. Marry. Emily: My idealized version of Dean -- Brie: Yeah. Emily: I would marry. Brie: Yeah. Yeah. Emily: But the Dean that’s actually on the show? Mm-mm. Fuckin’ leave. Sally: OK! (all laugh) Emily, singing: Have a holly, jolly Christmas … Sally: Um, earlier I was reading an article called -- Brie: Oh! Oh, yeah. Yeah. Emily: Don’t repeat it. It’s the worst. Sally: (laughing) Emily: I know we’re an explicit podcast, but this might be the line of what’s too explicit. Brie: (laugh) Sally: K, it was an article about monster erotica, and the title of the article is also a title for the book. -

ABSTRACT the Women of Supernatural: More Than

ABSTRACT The Women of Supernatural: More than Stereotypes Miranda B. Leddy, M.A. Mentor: Mia Moody-Ramirez, Ph.D. This critical discourse analysis of the American horror television show, Supernatural, uses a gender perspective to assess the stereotypes and female characters in the popular series. As part of this study 34 episodes of Supernatural and 19 female characters were analyzed. Findings indicate that while the target audience for Supernatural is women, the show tends to portray them in traditional, feminine, and horror genre stereotypes. The purpose of this thesis is twofold: 1) to provide a description of the types of female characters prevalent in the early seasons of Supernatural including mother-figures, victims, and monsters, and 2) to describe the changes that take place in the later seasons when the female characters no longer fit into feminine or horror stereotypes. Findings indicate that female characters of Supernatural have evolved throughout the seasons of the show and are more than just background characters in need of rescue. These findings are important because they illustrate that representations of women in television are not always based on stereotypes, and that the horror genre is evolving and beginning to depict strong female characters that are brave, intellectual leaders instead of victims being rescued by men. The female audience will be exposed to a more accurate portrayal of women to which they can relate and be inspired. Copyright © 2014 by Miranda B. Leddy All rights reserved TABLE OF CONTENTS Tables -

A University of Wisconsin Arboretum Narrative: Changing Landscapes and Changing Meaning

A University of Wisconsin Arboretum Narrative: Changing Landscapes and Changing Meaning Molly Evjen, Andreas Karlsson, Ryan Kelly, Matt Lamb Geography 565 Fall 2010 Abstract As societies change, so too does their relationship with the land. These changing relationships are reflected in and imprinted upon the land on which they live. In order to demonstrate how the landscape of the UW Arboretum has mirrored this changing association with nature through time, we have conducted an environmental history which focuses on four vignettes representing major changes in this relationship. Through research of primary data sources such as historical newsletters, observation, and plat map analysis our research shows that the Arboretum is a palimpsest of landforms and meaning resulting from these changing relationships. Introduction Environmental History is the study of the changing relationship between human beings and the natural world. We believe that the UW arboretum is a landscape that, through time, has been reflective of this changing relationship. Our purpose is to demonstrate how the landscape of the UW Arboretum has changed through time and how these changes reflect a cycle of changing, complex relationships between society and nature. We utilize multiple primary resources in our analysis such as plat maps, CCC newsletters, photographs, observations and personal reflections from our own field journals. We will demonstrate how the UW Arboretum is representative of this changing relationship in a number of ways. It is a reminder of early connections to the land represented by numerous burial mounds. The mounds also symbolize, through the multitude of possible interpretations of their purpose, people’s ever-changing interpretations of our relationship with nature in general. -

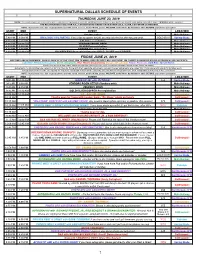

Supernatural Dallas Schedule of Events

SUPERNATURAL DALLAS SCHEDULE OF EVENTS THURSDAY, JUNE 20, 2019 NOTE: Pre-registration is not a necessity, just a convenience! Get your credentials, wristband and schedule so you don't have to wait again during convention days. VENDORS will be open too! PRE-REGISTRATION IS ONLY FOR FULL CONVENTION ATTENDEES WITH EITHER GOLD, SILVER, COPPER OR GA WEEKEND. NOTE: If you have solo, duo or group photo ops with Jared, Jensen, and/or Misha, please VALIDATE at the Photo Op Validation table BEFORE your photo op begins! START END EVENT LOCATION 3:30 PM 7:45 PM Vendors set-up Main Hallway 7:00 PM 9:30 PM BRI & DICK 'S PJ PARTY!!! If you’d like to register tonight, you may join the line after the party ends. SOLD OUT! Spring Glade 7:45 PM 8:30 PM GOLD Pre-registration Main Hallway 7:45 PM 10:00 PM VENDORS ROOM OPEN Main Hallway 8:30 PM 9:00 PM SILVER Pre-registration Main Hallway 9:00 PM 9:30 PM COPPER Pre-registration Main Hallway 9:30 PM 10:00 PM GA WEEKEND Pre-registration plus GOLD, SILVER and COPPER Main Hallway FRIDAY, JUNE 21, 2019 *END TIMES ARE APPROXIMATE. PLEASE SHOW UP AT THE START TIME TO MAKE SURE YOU DON’T MISS ANYTHING! WE CANNOT GUARANTEE MISSED AUTOGRAPHS OR PHOTO OPS. Light Blue: Private meet & greets, Green: Autographs, Red: Theatre programming, Orange: VIP schedule, Purple: Photo ops, Dark Blue: Special Events Photo ops are on a first come, first served basis (unless you're a VIP or unless otherwise noted in the Photo op listing) Autographs for Gold/Silver are called row by row, then by those with their separate autographs, pre-purchased autographs are called first. -

Constructing Community and Cosmos: a Bioarchaeological Analysis of Wisconsin Effigy Mound Mortuary Practices and Mound Construction

CONSTRUCTING COMMUNITY AND COSMOS: A BIOARCHAEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF WISCONSIN EFFIGY MOUND MORTUARY PRACTICES AND MOUND CONSTRUCTION By Wendy Lee Lackey-Cornelison A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILSOPHY Anthropology 2012 ABSTRACT CONSTRUCTING COMMUNITY AND COSMOS: A BIOARCHAEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF WISCONSIN EFFIGY MOUND MORTUARY PRACTICES AND MOUND CONSTRUCTION By Wendy Lee Lackey-Cornelison This dissertation presents an analysis of the mounds, human skeletal remains, grave goods, and ritual paraphernalia interred within mounds traditionally categorized as belonging to the Wisconsin Effigy Mound Tradition. The term ‘Effigy Mound Tradition’ commonly refers to a widespread mound building and ritual phenomenon that spanned the Upper Midwest during the Late Woodland (A.D. 600-A.D. 1150). Specifically, this study explores how features of mound construction and burial may have operated in the social structure of communities participating in this panregional ceremonial movement. The study uses previously excavated skeletal material, published archaeological reports, unpublished field notes, and photographs housed at the Milwaukee Public Museum to examine the social connotations of various mound forms and mortuary ritual among Wisconsin Effigy Mound communities. The archaeological and skeletal datasets consisted of data collected from seven mound sites with an aggregate sample of 197 mounds and a minimum number of individuals of 329. The mortuary analysis in this study explores whether the patterning of human remains interred within mounds were part of a system involved with the 1) creation of collective/ corporate identity, 2) denoting individual distinction and/or social inequality, or 3) a combination of both processes occurring simultaneously within Effigy Mound communities. -

Theology of Supernatural

religions Article Theology of Supernatural Pavel Nosachev School of Philosophy and Cultural Studies, HSE University, 101000 Moscow, Russia; [email protected] Received: 15 October 2020; Accepted: 1 December 2020; Published: 4 December 2020 Abstract: The main research issues of the article are the determination of the genesis of theology created in Supernatural and the understanding of ways in which this show transforms a traditional Christian theological narrative. The methodological framework of the article, on the one hand, is the theory of the occulture (C. Partridge), and on the other, the narrative theory proposed in U. Eco’s semiotic model. C. Partridge successfully described modern religious popular culture as a coexistence of abstract Eastern good (the idea of the transcendent Absolute, self-spirituality) and Western personified evil. The ideal confirmation of this thesis is Supernatural, since it was the bricolage game with images of Christian evil that became the cornerstone of its popularity. In the 15 seasons of its existence, Supernatural, conceived as a story of two evil-hunting brothers wrapped in a collection of urban legends, has turned into a global panorama of world demonology while touching on the nature of evil, the world order, theodicy, the image of God, etc. In fact, this show creates a new demonology, angelology, and eschatology. The article states that the narrative topics of Supernatural are based on two themes, i.e., the theology of the spiritual war of the third wave of charismatic Protestantism and the occult outlooks derived from Emmanuel Swedenborg’s system. The main topic of this article is the role of monotheistic mythology in Supernatural.