Immanuel Kant's Theory of Objects and Its Inherent Link to Natural

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kant's Theoretical Conception Of

KANT’S THEORETICAL CONCEPTION OF GOD Yaron Noam Hoffer Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Philosophy, September 2017 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee _________________________________________ Allen W. Wood, Ph.D. (Chair) _________________________________________ Sandra L. Shapshay, Ph.D. _________________________________________ Timothy O'Connor, Ph.D. _________________________________________ Michel Chaouli, Ph.D 15 September, 2017 ii Copyright © 2017 Yaron Noam Hoffer iii To Mor, who let me make her ends mine and made my ends hers iv Acknowledgments God has never been an important part of my life, growing up in a secular environment. Ironically, only through Kant, the ‘all-destroyer’ of rational theology and champion of enlightenment, I developed an interest in God. I was drawn to Kant’s philosophy since the beginning of my undergraduate studies, thinking that he got something right in many topics, or at least introduced fruitful ways of dealing with them. Early in my Graduate studies I was struck by Kant’s moral argument justifying belief in God’s existence. While I can’t say I was convinced, it somehow resonated with my cautious but inextricable optimism. My appreciation for this argument led me to have a closer look at Kant’s discussion of rational theology and especially his pre-critical writings. From there it was a short step to rediscover early modern metaphysics in general and embark upon the current project. This journey could not have been completed without the intellectual, emotional, and material support I was very fortunate to receive from my teachers, colleagues, friends, and family. -

What Is That Thing Called Philosophy of Technology? - R

HISTORY AND PHILOSOPHY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY – Vol. IV - What Is That Thing Called Philosophy of Technology? - R. J. Gómez WHAT IS THAT THING CALLED PHILOSOPHY OF TECHNOLOGY? R. J. Gómez Department of Philosophy. California State University (LA). USA Keywords: Adorno, Aristotle, Bunge, Ellul, Feenberg, Habermas, Heidegger, Horkheimer, Jonas, Latour, Marcuse, Mumford, Naess, Shrader-Frechette, artifact, assessment, determinism, ecosophy, ends, enlightenment, efficiency, epistemology, enframing, ideology, life-form, megamachine, metaphysics, method, naturalistic, fallacy, new, ethics, progress, rationality, rule, science, techno-philosophy Contents 1. Introduction 2. Locating technology with respect to science 2.1. Structure and Content 2.2. Method 2.3. Aim 2.4. Pattern of Change 3. Locating philosophy of technology 4. Early philosophies of technology 4.1. Aristotelianism 4.2. Technological Pessimism 4.3. Technological Optimism 4.4. Heidegger’s Existentialism and the Essence of Technology 4.5. Mumford’s Megamachinism 4.6. Neomarxism 4.6.1. Adorno-Horkheimer 4.6.2. Marcuse 4.6.3. Habermas 5. Recent philosophies of technology 5.1. L. Winner 5.2. A. Feenberg 5.3. EcosophyUNESCO – EOLSS 6. Technology and values 6.1. Shrader-Frechette Claims 6.2. H Jonas 7. Conclusions SAMPLE CHAPTERS Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch Summary A philosophy of technology is mainly a critical reflection on technology from the point of view of the main chapters of philosophy, e.g., metaphysics, epistemology and ethics. Technology has had a fast development since the middle of the 20th century , especially ©Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS) HISTORY AND PHILOSOPHY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY – Vol. IV - What Is That Thing Called Philosophy of Technology? - R. -

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry Jaap van Brakel Abstract: In this paper I assess the relation between philosophy of chemistry and (general) philosophy of science, focusing on those themes in the philoso- phy of chemistry that may bring about major revisions or extensions of cur- rent philosophy of science. Three themes can claim to make a unique contri- bution to philosophy of science: first, the variety of materials in the (natural and artificial) world; second, extending the world by making new stuff; and, third, specific features of the relations between chemistry and physics. Keywords : philosophy of science, philosophy of chemistry, interdiscourse relations, making stuff, variety of substances . 1. Introduction Chemistry is unique and distinguishes itself from all other sciences, with respect to three broad issues: • A (variety of) stuff perspective, requiring conceptual analysis of the notion of stuff or material (Sections 4 and 5). • A making stuff perspective: the transformation of stuff by chemical reaction or phase transition (Section 6). • The pivotal role of the relations between chemistry and physics in connection with the question how everything fits together (Section 7). All themes in the philosophy of chemistry can be classified in one of these three clusters or make contributions to general philosophy of science that, as yet , are not particularly different from similar contributions from other sci- ences (Section 3). I do not exclude the possibility of there being more than three clusters of philosophical issues unique to philosophy of chemistry, but I am not aware of any as yet. Moreover, highlighting the issues discussed in Sections 5-7 does not mean that issues reviewed in Section 3 are less im- portant in revising the philosophy of science. -

In Defence of Constructive Empiricism: Metaphysics Versus Science

To appear in Journal for General Philosophy of Science (2004) In Defence of Constructive Empiricism: Metaphysics versus Science F.A. Muller Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Mathematics Utrecht University, P.O. Box 80.000 3508 TA Utrecht, The Netherlands E-mail: [email protected] August 2003 Summary Over the past years, in books and journals (this journal included), N. Maxwell launched a ferocious attack on B.C. van Fraassen's view of science called Con- structive Empiricism (CE). This attack has been totally ignored. Must we con- clude from this silence that no defence is possible against the attack and that a fortiori Maxwell has buried CE once and for all, or is the attack too obviously flawed as not to merit exposure? We believe that neither is the case and hope that a careful dissection of Maxwell's reasoning will make this clear. This dis- section includes an analysis of Maxwell's `aberrance-argument' (omnipresent in his many writings) for the contentious claim that science implicitly and per- manently accepts a substantial, metaphysical thesis about the universe. This claim generally has been ignored too, for more than a quarter of a century. Our con- clusions will be that, first, Maxwell's attacks on CE can be beaten off; secondly, his `aberrance-arguments' do not establish what Maxwell believes they estab- lish; but, thirdly, we can draw a number of valuable lessons from these attacks about the nature of science and of the libertarian nature of CE. Table of Contents on other side −! Contents 1 Exordium: What is Maxwell's Argument? 1 2 Does Science Implicitly Accept Metaphysics? 3 2.1 Aberrant Theories . -

Beyond Skepticism Foundationalism and the New Fuzziness: the Role of Wide Reflective Equilibrium in Legal Theory Robert Justin Lipkin

Cornell Law Review Volume 75 Article 2 Issue 4 May 1990 Beyond Skepticism Foundationalism and the New Fuzziness: The Role of Wide Reflective Equilibrium in Legal Theory Robert Justin Lipkin Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Robert Justin Lipkin, Beyond Skepticism Foundationalism and the New Fuzziness: The Role of Wide Reflective Equilibrium in Legal Theory , 75 Cornell L. Rev. 810 (1990) Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr/vol75/iss4/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BEYOND SKEPTICISM, FOUNDATIONALISM AND THE NEW FUZZINESS: THE ROLE OF WIDE REFLECTIVE EQUILIBRIUM IN LEGAL THEORY Robert Justin Liphint TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .............................................. 812 I. FOUNDATIONALISM AND SKEPTICISM ..................... 816 A. The Problem of Skepticism ........................ 816 B. Skepticism and Nihilism ........................... 819 1. Theoretical and PracticalSkepticism ................ 820 2. Subjectivism and Relativism ....................... 821 3. Epistemic and Conceptual Skepticism ................ 821 4. Radical Skepticism ............................... 822 C. Modified Skepticism ............................... 824 II. NEW FOUNDATIONALISM -

Science, Subjectivity & Reality

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Science and Religion Dialogue Prints Journal of Consciousness Exploration & Research| April 2016 | Volume 7 | Issue 4 | pp. 333-336 333 Pereira, C. & Reddy, J. S. K., On Science & Phenomenology in Consciousness Studies Perspective Science, Subjectivity & Reality * Contzen Pereira & J. S. K. Reddy Abstract In this paper, we argue on the ability of science to capture the true subjective experience of life, blinded within the limits of its reductionist approaches. With this approach, even though science can explain well the physics behind the objective phenomenon, it fails fundamentally in understanding the various aspects associated with the biological entities. In this sense, we are skeptical to the present approach of science and calls out for a more fundamental theory of life that considers not only the objectivity aspect of a biological entity but also the subjective experience as well. It raises questions as to what does it takes to develop a new science from a subjective standpoint. Key Words: Science, subjectivity, reality, cosmos, peripersonal space. Modern science is based on the principle “Give us one free miracle and we’ll explain the rest.” The one free miracle is the appearance of all the matter and energy in the universe and all the laws that govern it from nothing, in a single instant - Terrence McKenna The Cosmos showers the experience of life graced by an enigmatic subject grounded in an objective fabric (or biological structure). The extent of the subjective experience is in a way bounded by the limitations of an objective fabric. -

Leibniz on Consciousness and Self-Consciousness Rocco J

Leibniz on Consciousness and Self-Consciousness Rocco J. Gennaro [Final version in NEW ESSAYS ON THE RATIONALISTS, Oxford U Press, 1999] In this paper I discuss the so-called "higher-order thought theory of consciousness" (the HOT theory) with special attention to how Leibnizian theses can help support it and how it can shed light on Leibniz's theory of perception, apperception, and consciousness. It will become clear how treating Leibniz as a HOT theorist can solve some of the problems he faced and some of the puzzles posed by commentators, e.g. animal mentality and the role of reason and memory in self-consciousness. I do not hold Leibniz's metaphysic of immaterial simple substances (i.e. monads), but even a contemporary materialist can learn a great deal from him. 1. What is the HOT Theory? In the absence of any plausible reductionist account of consciousness in nonmentalistic terms, the HOT theory says that the best explanation for what makes a mental state conscious is that it is accompanied by a thought (or awareness) that one is in that state.1 The sense of 'conscious state' I have in mind is the same as Nagel's sense, i.e. there is 'something it is like to be in that state' from a subjective or first-person point of view.2 Now, when the conscious mental state is a first-order world-directed state the HOT is not itself conscious; otherwise, circularity and an infinite regress would follow. Moreover, when the higher-order thought (HOT) is itself conscious, there is a yet higher-order (or third-order) thought directed at the second-order state. -

Spinoza and the Sciences Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science

SPINOZA AND THE SCIENCES BOSTON STUDIES IN THE PHILOSOPHY OF SCIENCE EDITED BY ROBERT S. COHEN AND MARX W. WARTOFSKY VOLUME 91 SPINOZA AND THE SCIENCES Edited by MARJORIE GRENE University of California at Davis and DEBRA NAILS University of the Witwatersrand D. REIDEL PUBLISHING COMPANY A MEMBER OF THE KLUWER ~~~.'~*"~ ACADEMIC PUBLISHERS GROUP i\"lI'4 DORDRECHT/BOSTON/LANCASTER/TOKYO Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Main entry under title: Spinoza and the sciences. (Boston studies in the philosophy of science; v. 91) Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Spinoza, Benedictus de, 1632-1677. 2. Science- Philosophy-History. 3. Scientists-Netherlands- Biography. I. Grene, Marjorie Glicksman, 1910- II. Nails, Debra, 1950- Ill. Series. Q174.B67 vol. 91 OOI'.Ols 85-28183 101 43.S725J 100 I J ISBN-13: 978-94-010-8511-3 e-ISBN-13: 978-94-009-4514-2 DOl: 10.1007/978-94-009-4514-2 Published by D. Reidel Publishing Company, P.O. Box 17, 3300 AA Dordrecht, Holland. Sold and distributed in the U.S.A. and Canada by Kluwer Academic Publishers, 101 Philip Drive, Assinippi Park, Norwell, MA 02061, U.S.A. In all other countries, sold and distributed by Kluwer Academic Publishers Group, P.O. Box 322, 3300 AH Dordrecht, Holland. 2-0490-150 ts All Rights Reserved © 1986 by D. Reidel Publishing Company Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1986 and copyright holders as specified on appropriate pages within No part of the material protected by this copyright notice may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the copyright owner FROM SPINOZA'S LETTER TO OLDENBURG, RIJNSBURG, APRIL, 1662 (Photo by permission of Berend Kolk) TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ix MARJORIE GRENE I Introduction xi 1. -

Aristotelian Habitus and the Power of the Embodied Self: Reflections on the Insights Gained from the Fakirs in Bangladesh

23 Bangladesh e-Journal of Sociology. Volume 17, Number 2. July 2020. Aristotelian Habitus and the Power of the Embodied Self: Reflections on the Insights Gained from the Fakirs in Bangladesh Mohammad Golam Nabi Mozumder1, Abstract: This article traces back classical Greek and Medieval meanings of habitus to show that Bourdieu’s redefinition of habitus discarded a seminal feature of Aristotelian habitus—the power of radically transforming the self at will. I elaborate how the practices of purposefully training the embodied self remains marginalized in Pierre Bourdieu’s re-conceptualization of habitus. Examining Aristotle’s habitus, this paper brings back the focus on the long-neglected insight of the power of deliberately (re)training the self in constructing a heterodox but ethical way of being and socializing. As an example, I refer to the Fakirs in current Bangladesh, who cultivate antinomian life-practices. The main argument of the paper is that habitus in Bourdieu’s formulations is less suitable than Aristotle’s in analysing the praxis of the Fakirs. I suggest that instead of sticking to a universal conceptualization of habitus, sociologists should consider with equal importance both models of habitus articulated by Aristotle and Bourdieu. Doing that could benefit contemporary sociology in two ways: First, Aristotle’s conceptualization of habitus is an important tool in identifying the sociological importance of the praxis of marginalized groups, e.g., Fakirs in Bangladesh; and second, extending the focus of a key sociological concept, i.e., habitus, addresses the apparent disconnect between the wisdom of heterodox practitioners in the Global South and dominant social theories built upon the analyses of European and American social traditions. -

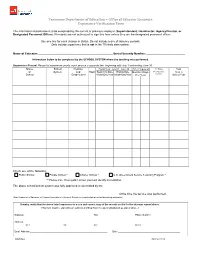

Experience Verification Form

Tennessee Department of Education – Office of Educator Licensure Experience Verification Form The information listed below is to be completed by the current or previous employer (Superintendent, Headmaster, Agency Director, or Designated Personnel Officer). Principals are not authorized to sign this form unless they are the designated personnel officer. Use one line for each change in status. Do not include leave of absence periods. Only include experience that is not in the TN state data system. Name of Educator: ________________________________________________ Social Security Number: _________________________ Information below to be completed by the SCHOOL SYSTEM where the teaching was performed. Experience Record: Please list experience yearly, each year on a separate line, beginning with July 1 and ending June 30. Name School Position Fiscal Year, July 01 - June 30 Time Employed % Time, Total of System and State Beginning Date Ending Date Months / Days Ex. Part-time, Days in Month/Day/Year Month/Day/Year Full-time School Year School Grade Level Per Year Check one of the following: Public School Private School * Charter School * U.S. Government Service Teaching Program * ** Please note: If non-public school you must identify accreditation. The above school/school system was fully approved or accredited by the ____________________________________________________________________ at the time the service was performed. (State Department of Education, or Regional Association of Colleges & Schools, or recognized private school accrediting -

Newton.Indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 16-11-12 / 14:45 | Pag

omslag Newton.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 16-11-12 / 14:45 | Pag. 1 e Dutch Republic proved ‘A new light on several to be extremely receptive to major gures involved in the groundbreaking ideas of Newton Isaac Newton (–). the reception of Newton’s Dutch scholars such as Willem work.’ and the Netherlands Jacob ’s Gravesande and Petrus Prof. Bert Theunissen, Newton the Netherlands and van Musschenbroek played a Utrecht University crucial role in the adaption and How Isaac Newton was Fashioned dissemination of Newton’s work, ‘is book provides an in the Dutch Republic not only in the Netherlands important contribution to but also in the rest of Europe. EDITED BY ERIC JORINK In the course of the eighteenth the study of the European AND AD MAAS century, Newton’s ideas (in Enlightenment with new dierent guises and interpre- insights in the circulation tations) became a veritable hype in Dutch society. In Newton of knowledge.’ and the Netherlands Newton’s Prof. Frans van Lunteren, sudden success is analyzed in Leiden University great depth and put into a new perspective. Ad Maas is curator at the Museum Boerhaave, Leiden, the Netherlands. Eric Jorink is researcher at the Huygens Institute for Netherlands History (Royal Dutch Academy of Arts and Sciences). / www.lup.nl LUP Newton and the Netherlands.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 16-11-12 / 16:47 | Pag. 1 Newton and the Netherlands Newton and the Netherlands.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 16-11-12 / 16:47 | Pag. 2 Newton and the Netherlands.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 16-11-12 / 16:47 | Pag. -

A Feminist Epistemological Framework: Preventing Knowledge Distortions in Scientific Inquiry

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2019 A Feminist Epistemological Framework: Preventing Knowledge Distortions in Scientific Inquiry Karina Bucciarelli Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses Part of the Epistemology Commons, Feminist Philosophy Commons, and the Philosophy of Science Commons Recommended Citation Bucciarelli, Karina, "A Feminist Epistemological Framework: Preventing Knowledge Distortions in Scientific Inquiry" (2019). Scripps Senior Theses. 1365. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/1365 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A FEMINIST EPISTEMOLOGICAL FRAMEWORK: PREVENTING KNOWLEDGE DISTORTIONS IN SCIENTIFIC INQUIRY by KARINA MARTINS BUCCIARELLI SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS PROFESSOR SUSAN CASTAGNETTO PROFESSOR RIMA BASU APRIL 26, 2019 Bucciarelli 2 Acknowledgements First off, I would like to thank my wonderful family for supporting me every step of the way. Mamãe e Papai, obrigada pelo amor e carinho, mil telefonemas, conversas e risadas. Obrigada por não só proporcionar essa educação incrível, mas também me dar um exemplo de como viver. Rafa, thanks for the jokes, the editing help and the spontaneous phone calls. Bela, thank you for the endless time you give to me, for your patience and for your support (even through WhatsApp audios). To my dear friends, thank you for the late study nights, the wild dance parties, the laughs and the endless support.