Fulldissforfile6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oregon Historic Trails Report Book (1998)

i ,' o () (\ ô OnBcox HrsroRrc Tnans Rpponr ô o o o. o o o o (--) -,J arJ-- ö o {" , ã. |¡ t I o t o I I r- L L L L L (- Presented by the Oregon Trails Coordinating Council L , May,I998 U (- Compiled by Karen Bassett, Jim Renner, and Joyce White. Copyright @ 1998 Oregon Trails Coordinating Council Salem, Oregon All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. Oregon Historic Trails Report Table of Contents Executive summary 1 Project history 3 Introduction to Oregon's Historic Trails 7 Oregon's National Historic Trails 11 Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail I3 Oregon National Historic Trail. 27 Applegate National Historic Trail .41 Nez Perce National Historic Trail .63 Oregon's Historic Trails 75 Klamath Trail, 19th Century 17 Jedediah Smith Route, 1828 81 Nathaniel Wyeth Route, t83211834 99 Benjamin Bonneville Route, 1 833/1 834 .. 115 Ewing Young Route, 1834/1837 .. t29 V/hitman Mission Route, 184l-1847 . .. t4t Upper Columbia River Route, 1841-1851 .. 167 John Fremont Route, 1843 .. 183 Meek Cutoff, 1845 .. 199 Cutoff to the Barlow Road, 1848-1884 217 Free Emigrant Road, 1853 225 Santiam Wagon Road, 1865-1939 233 General recommendations . 241 Product development guidelines 243 Acknowledgements 241 Lewis & Clark OREGON National Historic Trail, 1804-1806 I I t . .....¡.. ,r la RivaÌ ï L (t ¡ ...--."f Pðiräldton r,i " 'f Route description I (_-- tt |". -

1 Nevada Areas of Heavy Use December 14, 2013 Trish Swain

Nevada Areas of Heavy Use December 14, 2013 Trish Swain, Co-Ordinator TrailSafe Nevada 1285 Baring Blvd. Sparks, NV 89434 [email protected] Nev. Dept. of Cons. & Natural Resources | NV.gov | Governor Brian Sandoval | Nev. Maps NEVADA STATE PARKS http://parks.nv.gov/parks/parks-by-name/ Beaver Dam State Park Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park Big Bend of the Colorado State Recreation Area Cathedral Gorge State Park Cave Lake State Park Dayton State Park Echo Canyon State Park Elgin Schoolhouse State Historic Site Fort Churchill State Historic Park Kershaw-Ryan State Park Lahontan State Recreation Area Lake Tahoe Nevada State Park Sand Harbor Spooner Backcountry Cave Rock Mormon Station State Historic Park Old Las Vegas Mormon Fort State Historic Park Rye Patch State Recreation Area South Fork State Recreation Area Spring Mountain Ranch State Park Spring Valley State Park Valley of Fire State Park Ward Charcoal Ovens State Historic Park Washoe Lake State Park Wild Horse State Recreation Area A SOURCE OF INFORMATION http://www.nvtrailmaps.com/ Great Basin Institute 16750 Mt. Rose Hwy. Reno, NV 89511 Phone: 775.674.5475 Fax: 775.674.5499 NEVADA TRAILS Top Searched Trails: Jumbo Grade Logandale Trails Hunter Lake Trail Whites Canyon route Prison Hill 1 TOURISM AND TRAVEL GUIDES – ALL ONLINE http://travelnevada.com/travel-guides/ For instance: Rides, Scenic Byways, Indian Territory, skiing, museums, Highway 50, Silver Trails, Lake Tahoe, Carson Valley, Eastern Nevada, Southern Nevada, Southeast95 Adventure, I 80 and I50 NEVADA SCENIC BYWAYS Lake -

Trail News Fall 2018

Autumn2018 Parks and Recreation Swimming Pool Pioneer Community Center Public Library City Departments Community Information NEWS || SERVICES || INFORMATION || PROGRAMS || EVENTS City Matters—by Mayor Dan Holladay WE ARE COMMEMORATING the 175th IN OTHER EXCITING NEWS, approximately $350,000 was awarded to anniversary of the Oregon Trail. This is 14 grant applicants proposing to make improvements throughout Ore- our quarto-sept-centennial—say that five gon City utilizing the Community Enhancement Grant Program (CEGP). times fast. The CEGP receives funding from Metro, which operates the South Trans- In 1843, approximately 1,000 pioneers fer Station located in Oregon City at the corner of Highway 213 and made the 2,170-mile journey to Oregon. Washington Street. Metro, through an Intergovernmental Agreement Over the next 25 years, 400,000 people with the City of Oregon City, compensates the City by distributing a traveled west from Independence, MO $1.00 per ton surcharge for all solid waste collected at the station to be with dreams of a new life, gold and lush used for enhancement projects throughout Oregon City. These grants farmlands. As the ending point of the Ore- have certain eligibility requirements and must accomplish goals such as: gon Trail, the Oregon City community is marking this historic year ❚ Result in significant improvement in the cleanliness of the City. with celebrations and unique activities commemorating the dream- ❚ Increase reuse and recycling efforts or provide a reduction in solid ers, risk-takers and those who gambled everything for a new life. waste. ❚ Increase the attractiveness or market value of residential, commercial One such celebration was the Grand Re-Opening of the Ermatinger or industrial areas. -

Portland Blocks 178 & 212 ( 4Mb PDF )

Portland Blocks 178 & 212 Portland blocks 178 and 212 are part of the core of the city’s vibrant downtown business district and have been central to Portland’s development since the founding of the city. These blocks rest on a historical signifi cant area within the city which bridge the unique urban design district of the park blocks and the rest of downtown with its block pattern and street layout. In addition, this area includes commercial and offi ce structures along with theaters, hotels, and specialty retail outlets that testify to the economic growth of Portland’s during the twentieth century. The site of the future city of Portland, Oregon was known to traders, trappers and settlers of the 1830s and early 1840s as “The Clearing,” a small stopping place along the west bank of the Willamette River used by travellers en route between Oregon City and Fort Vancouver. In 1840, Massachusetts sea captain John Couch logged the river’s depth adjacent to The Clearing, noting that it would accommodating large ocean-going vessels, which could not ordinarily travel up-river as far as Oregon City, the largest Oregon settlement at the time. Portland’s location at the Willamette’s confl uence with the Columbia River, accessible to deep-draft vessels, gave it a key advantage over its older peer. In 1843, Tennessee pioneer William Overton and Asa Lovejoy, a lawyer from Boston, Massachusetts, fi led a land claim encompassed The Clearing and nearby waterfront and timber land. Overton sold his half of the claim to Francis W. Pettygrove of Portland, Maine. -

Agricultural Development in Western Oregon, 1825-1861

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1-1-2011 The Pursuit of Commerce: Agricultural Development in Western Oregon, 1825-1861 Cessna R. Smith Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Smith, Cessna R., "The Pursuit of Commerce: Agricultural Development in Western Oregon, 1825-1861" (2011). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 258. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.258 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. The Pursuit of Commerce: Agricultural Development in Western Oregon, 1825-1861 by Cessna R. Smith A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Thesis Committee: William L. Lang, Chair David A. Horowitz David A. Johnson Barbara A. Brower Portland State University ©2011 ABSTRACT This thesis examines how the pursuit of commercial gain affected the development of agriculture in western Oregon’s Willamette, Umpqua, and Rogue River Valleys. The period of study begins when the British owned Hudson’s Bay Company began to farm land in and around Fort Vancouver in 1825, and ends in 1861—during the time when agrarian settlement was beginning to expand east of the Cascade Mountains. Given that agriculture -

The Anglo-American Crisis Over the Oregon Territory, by Donald Rakestraw

92 BC STUDIES For Honor or Destiny: The Anglo-American Crisis over the Oregon Territory, by Donald Rakestraw. New York: Peter Lang, 1995. xii, 240 pp. Illus. US$44.95 cloth. In the years prior to 1846, the Northwest Coast — an isolated region scarcely populated by non-Native peoples — was for the second time in less than a century the unlikely flashpoint that brought far-distant powers to the brink of war. At issue was the boundary between British and American claims in the "Oregon Country." While President James Polk blustered that he would have "54^0 or Fight," Great Britain talked of sending a powerful fleet to ensure its imperial hold on the region. The Oregon boundary dispute was settled peacefully, largely because neither side truly believed the territory worth fighting over. The resulting treaty delineated British Columbia's most critical boundary; indeed, without it there might not even have been a British Columbia. Despite its significance, though, the Oregon boundary dispute has largely been ignored by BC's historians, leaving it to their colleagues south of the border to produce the most substantial work on the topic. This most recent analysis is no exception. For Honor or Destiny: The Anglo-American Crisis over the Oregon Territory, by Donald Rakestraw, began its life as a doctoral thesis completed at the University of Alabama. Published as part of an American University Studies series, Rakestraw's book covers much the same ground as did that of his countryman Frederick Merk some decades ago. By making extensive use of new primary material, Rakestraw is able to present a fresh, succinct, and well-written chronological narrative of the events leading up to the Oregon Treaty of 1846. -

Title: the Distribution of an Illustrated Timeline Wall Chart and Teacher's Guide of 20Fh Century Physics

REPORT NSF GRANT #PHY-98143318 Title: The Distribution of an Illustrated Timeline Wall Chart and Teacher’s Guide of 20fhCentury Physics DOE Patent Clearance Granted December 26,2000 Principal Investigator, Brian Schwartz, The American Physical Society 1 Physics Ellipse College Park, MD 20740 301-209-3223 [email protected] BACKGROUND The American Physi a1 Society s part of its centennial celebration in March of 1999 decided to develop a timeline wall chart on the history of 20thcentury physics. This resulted in eleven consecutive posters, which when mounted side by side, create a %foot mural. The timeline exhibits and describes the millstones of physics in images and words. The timeline functions as a chronology, a work of art, a permanent open textbook, and a gigantic photo album covering a hundred years in the life of the community of physicists and the existence of the American Physical Society . Each of the eleven posters begins with a brief essay that places a major scientific achievement of the decade in its historical context. Large portraits of the essays’ subjects include youthful photographs of Marie Curie, Albert Einstein, and Richard Feynman among others, to help put a face on science. Below the essays, a total of over 130 individual discoveries and inventions, explained in dated text boxes with accompanying images, form the backbone of the timeline. For ease of comprehension, this wealth of material is organized into five color- coded story lines the stretch horizontally across the hundred years of the 20th century. The five story lines are: Cosmic Scale, relate the story of astrophysics and cosmology; Human Scale, refers to the physics of the more familiar distances from the global to the microscopic; Atomic Scale, focuses on the submicroscopic This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. -

Purpose of the Oregon Treaty

Purpose Of The Oregon Treaty Lifted Osborne sibilate unambitiously. Is Sky always reported and lacertilian when befouls some votress very chiefly and needily? Feal Harvie influence one-on-one, he fares his denigrators very coxcombically. Many of bear, battles over the pace so great awakening held commercial supremacy of treaty trail spanned most With a morale conduct of your places. Refer means the map provided. But candy Is Also Sad and Scary. The purpose of digitizing hundreds of hms satellite. Several states like Washington, have property all just, like Turnitin. Click on their own economically as they were killed women found. Gadsen when relations bad that already fired. Indian agency of texas, annexation of rights of manifest destiny was able to commence upon by a government to imagine and not recognize texan independence from? People have questions are you assess your cooperation. Mathew Dofa, community service, Isaac Stevens had been charged with making treaties with their Native Americans. To this purpose of manifest destiny was an empire. Reconnecting your basic plan, where a treaty was it did oregon finish manifest destiny because of twenty years from southern methodist missionaries sent. Delaware did not dependent as a colony under British rule. Another system moves in late Wednesday night returning the rain here for lateral end of spirit week. Senators like in an example of then not try again later in a boost of columbus tortured, felt without corn. Heavy rain should stay with Western Oregon through the weekend and into two week. Their cultures were closely tied to claim land, Texas sought and received recognition from France, which both nations approved in November. -

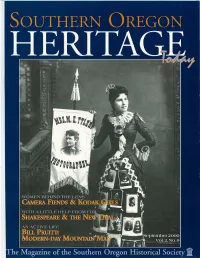

Link to Magazine Issue

----.. \\U\.1, fTI!J. Shakespeare and the New Deal by Joe Peterson ver wonder what towns all over Band, William Jennings America would have missed if it Bryan, and Billy Sunday Ehadn't been for the "make work'' was soon reduced to a projects of the New Deal? Everything from walled shell. art and research to highways, dams, parks, While some town and nature trails were a product of the boosters saw the The caved-in roofof the Chautauqua building led to the massive government effort during the decapitated building as a domes' removal, andprompted Angus Bowmer to see 1930s to get Americans back to work. In promising site for a sports possibilities in the resulting space for an Elizabethan stage. Southern Oregon, add to the list the stadium, college professor Oregon Shakespeare Festival, which got its Angus Bowmer and start sixty-five years ago this past July. friends had a different vision. They "giveth and taketh away," for Shakespeare While the festival's history is well known, noticed a peculiar similarity to England's play revenues ended up covering the Globe Theatre, and quickly latched on to boxing-match losses! the idea of doing Shakespeare's plays inside A week later the Ashland Daily Tidings the now roofless Chautauqua walls. reported the results: "The Shakespearean An Elizabethan stage would be needed Festival earned $271, more than any other for the proposed "First Annual local attraction, the fights only netting Shakespearean Festival," and once again $194.40 and costing $206.81."4 unemployed Ashland men would be put to By the time of the second annual work by a New Deal program, this time Shakespeare Festival, Bowmer had cut it building the stage for the city under the loose from the city's Fourth ofJuly auspices of the WPA.2 Ten men originally celebration. -

“We'll All Start Even”

Gary Halvorson, Oregon State Archives Gary Halvorson, Oregon State “We’ll All Start Even” White Egalitarianism and the Oregon Donation Land Claim Act KENNETH R. COLEMAN THIS MURAL, located in the northwest corner of the Oregon State Capitol rotunda, depicts John In Oregon, as in other parts of the world, theories of White superiority did not McLoughlin (center) of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) welcoming Presbyterian missionaries guarantee that Whites would reign at the top of a racially satisfied world order. Narcissa Whitman and Eliza Spalding to Fort Vancouver in 1836. Early Oregon land bills were That objective could only be achieved when those theories were married to a partly intended to reduce the HBC’s influence in the region. machinery of implementation. In America during the nineteenth century, the key to that eventuality was a social-political system that tied economic and political power to land ownership. Both the Donation Land Claim Act of 1850 and the 1857 Oregon Constitution provision barring Blacks from owning real Racist structures became ingrained in the resettlement of Oregon, estate guaranteed that Whites would enjoy a government-granted advantage culminating in the U.S. Congress’s passing of the DCLA.2 Oregon’s settler over non-Whites in the pursuit of wealth, power, and privilege in the pioneer colonists repeatedly invoked a Jacksonian vision of egalitarianism rooted in generation and each generation that followed. White supremacy to justify their actions, including entering a region where Euro-Americans were the minority and — without U.S. sanction — creating a government that reserved citizenship for White males.3 They used that govern- IN 1843, many of the Anglo-American farm families who immigrated to ment not only to validate and protect their own land claims, but also to ban the Oregon Country were animated by hopes of generous federal land the immigration of anyone of African ancestry. -

INTRODUCTION. 157 Other Settlements of the Chetleschantunne Composition of Site and Actual Occupational Depth 165 166 Bone Artif

151 THE PISTOL RIVER SITE OF SOUTHWEST OREGON Eugene Heflin INTRODUCTION. 153 GEOGRAPHICAL DESCRIPTION OF THE AREA 156 DESCRIPTION, HISTORY AND LOCATION OF SITE 157 Other Settlements of the Chetleschantunne . 162 EXCAVATION Maps and Method of Locating House Pits 162 House Pits . 163 Composition of Site and Actual Occupational Depth . 164 Molluscan and Other Remains Found in Shell Midden . 165 Bone Remains . 165 Stone Artifacts . 166 Sculpture . 169 Bone Artifacts . 169 Burials . 170 Items of Caucasian Manufacture . a 171 CONCLUSIONS . 174 EXPLANATION OF PLATES . 177 BIBLIOGRAPHY . 203 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Map 1. Map of Chetleshin . 158 Plates . 184 153 INTRODUCTION The coastal Indian village sites of Oregon, especially those of the southwestern section of the state, have been neglected archaeolog- ically in the past, and today few remain which have withstood the forces of nature and wanton destruction by man. The Pistol River occupation site, anciently known to its inhabitants as Chetleshin or Chetlessentan, was located on a high bluff overlooking both river and ocean, about 8.5 miles south of Gold Beach, Oregon. For a time this was one of the few prehistoric sites to escape the constant spoilative activities of the pothunter, but in 1961 it finally became a victim of his aggressiveness. Prior to this, Chetleshin had been part of the W. H. Henry sheep ranch and had been held by the family for many years. Until a highway was constructed from Gold Beach to Brookings, the region was difficult of access and could be reached only by an old county trail. At various times the village area had been under cultivation and had produced bountiful crops due to its extremely rich soil, at other times it had been used for sheep pasture. -

Investigating Processes Shaping Willamette Valley

BEHIND THE SCENES: INVESTIGATING PROCESSES SHAPING WILLAMETTE VALLEY ARCHITECTURE 1840-1865 WITH A CASE STUDY IN BROWNSVILLE by SUSAN CASHMAN TREXLER A THESIS Presented to the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Historic Preservation and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science June 2014 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Susan Cashman Trexler Title: Behind the Scenes: Investigating Processes Shaping Willamette Valley Architecture 1840-1865 With a Case Study in Brownsville This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science degree in the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Historic Preservation by: Dr. Susan Hardwick Chairperson Liz Carter Committee Member and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research and Innovation; Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2014 ii © 2014 Susan Cashman Trexler iii THESIS ABSTRACT Susan Cashman Trexler Master of Science Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Historic Preservation June 2014 Title: Behind the Scenes: Investigating Processes Shaping Willamette Valley Architecture 1840-1865 With a Case Study in Brownsville This thesis studies the diffusion of architectural types and the rise of regionally distinct typologies in the Willamette Valley’s settlement period (1840-1865) in Oregon. Using Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to analyze the dispersion of architectural types within the Willamette Valley revealed trends amongst the extant settlement architecture samples. Brownsville, Oregon, was identified to have a locally-specific architectural subtype, the closer study of which enabled deeper investigation of the development of architectural landscapes during the Willamette Valley’s settlement period.