1998 Annual Report Workingworking Smartersmarter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Michigan Department of Corrections

MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS “Committed to Protect, Dedicated to Success” FY2021 FIVE YEAR ASSESSMENT PLAN SUMMARY The mission of the Michigan Department of Corrections is to create a safer Michigan by holding offenders accountable while promoting their success. The following is the Michigan Department of Corrections Five Year Plan Summary. This plan includes MDOC project priorities for 30 correctional facilities currently open and in full operation. This list encompasses prisons that have been in service since 1889 (Marquette Branch Prison) to the newest prison built in 2001 (Bellamy Creek Correctional Facility). These 30 open facilities consisting of 1,054 buildings equaling 7.4 million square feet sitting on 4,542 acres. The MDOC must provide a full range of services similar to a small community. These prison complexes must function in a safe and secure manner to ensure public, staff and prisoner safety 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, 365 days a year. In addition to the operational sites, MDOC is responsible for maintaining closed facilities. This group of closed facilities consists of 305 buildings equaling 4.8 million square feet on an additional 1,645 acres. The MDOC Physical Plant Division with assistance from a large group of Physical Plant Supervisors conduct annual assessments of all Facilities using standardized assessment processes. All available staff who possess the appropriate expertise participate in this process to ensure a diverse skill set, participate in the study and to ensure quality results. Each of our facilities is similar to a small city where prisoners are provided shelter, clothing, health care, psychological care, education, recreation, and religious needs. -

Corrections Connection

Corrections Connection Volume 30, Issue 3 March 2018 Corrections Connection March 2018 2 In this issue: An Alternative Path 3 Field Days Podcast 5 Hiring efforts 6 West Shoreline update 7 Women in corrections 7 Parole supervisor makes history 8 New wardens 8 Recognized Recruit 9 Department leaders retire 10 Remembering Agent Taylor 10 Fire Truck Pull 10 Legislative update 11 Battle of the Badges 11 The Voice 11 The Extra Mile 12 Corrections Quiz 16 Employee Recreation Day 16 Snapshots 17 Corrections in the News 17 Seen on Social Media 17 New hires 18 Retirements 19 Corrections Connection is a publication of the The image on the cover was taken at Dow Gardens in Office of Public Information and Communications. Midland by Kerri Huizar, Bay County Circuit Court Probation Story ideas, feedback and comments can Supervisor. For the chance to have your photo featured on the cover of be submitted to Holly Kramer at KramerH@ the newsletter, email a high-resolution version of the image michigan.gov. and a description of where it was taken to Holly Kramer at Like MDOC on Facebook or follow us on Twitter. [email protected]. Committed to Protect, Dedicated to Success Corrections Connection March 2018 3 An Alternative Path drill and ceremony field, who responded with an Special Alternative enthusiastic “Oorah!” For 30 years, the program has offered intensive Incarceration military-style discipline, programming and service work designed to help offenders set their lives in a program closes in on positive direction. It aims to instill positive values and a sense of respect for oneself and others. -

NHL Scoort Met Outdoorwedstrijden

WWW.SPORTENSTRATEGIE.NL FEBRUARI 2014 // JAARGANG 8 // EDITIE 1 27 THE AMERICAN WAY NHL scoort met outdoorwedstrijden De National Hockey League (NHL) is de kleinste van de vier grote Amerikaanse sportleagues. In de competitieve Noord-Amerikaanse sportmarkt moet de ijshockeyleague hard werken om in beeld te blijven. Een bizar idee heeft de sport afgelopen jaren een geweldige impuls gegeven: outdoorijshockey! NBC de uitzendrechten van de NHL over- Winter Classic had zijn naam gevestigd, genomen van ABC. Vanaf dat moment en in de jaren daarna volgden outdoor- probeerde NBC-vicepresident Jon Miller wedstrijden in Boston (2010), Pittsburgh de NHL-leiding warm te krijgen voor een (2011) en Philadelphia (2012). Elk jaar sneu- jaarlijkse Winter Classic. De league zag velden er records. In 2010 kwamen voor echter nog steeds vooral praktische pro- de 38.000 beschikbare tickets maar liefst blemen. Twee ontwikkelingen brachten 310.000 aanvragen binnen. De wedstrijd het idee van een jaarlijkse outdoor-NHL- in 2011, met de absolute topspelers Sidney wedstrijd in een stroomversnelling. Crosby en Alex Ovechkin, brak met 4,5 mil- joen kijkers het televisierecord van 2009. In 2006 slaagde NBC er niet in zijn contract met de Gator Bowl te verlengen. Deze fina- Tussen de palmen lewedstrijd van het college football wordt Door een conflict tussen eigenaren en traditiegetrouw op de eerste dag van het spelers werd de Winter Classic van 2013 jaar gespeeld en is daarmee een gega- afgeblazen, maar dit jaar komt de NHL met randeerde kijkcijferhit. Door het afketsen maar liefst zes outdoorwedstrijden sterker van de deal zat NBC met een gevoelig gat terug dan ooit. -

MAP CFA-Prosperity Regions-Ka

Michigan Department of Corrections Correctional Facilities Map As of January 1, 2017 Kewee- naw Houghton Ontonagon l 2 Baraga Gogebic Luce Marquette l 3 l4 l 5 Chippewa l 1 Alger ll 6 Schoolcraft Iron Mackinac Dickinson Delta Emmet Cheboy- Menom- gan inee Presque Isle Charlevoix Alpena Otsego Mont- lCorrectional Facilities Antrim morency 1. Ojibway Correctional Facility Leelanau Grand Oscoda Alcona 2. Baraga Correctional Facility Benzie Traverse Kalkaska 3. Marquette Branch Prison* Crawford 4. Alger Correctional Facility Ogemaw Iosco 5. Newberry Correctional Facility Manistee Wexford Missau- Roscom- mon 6. Chippewa Correctional Facility l7 kee 6. Kinross Correctional Facility Arenac 7. Oaks Correctional Facility Mason Lake Osceola Clare Gladwin Huron 8. Earnest C. Brooks Correctional Facility 8. West Shoreline Correctional Facility Midland Bay Mecosta Isabella Tuscola Oceana 8. Muskegon Correctional Facility Neway- l go 10 Sanilac 9. Central Michigan Correctional Facility ll Muske- Montcalm 9 Saginaw 9. St. Louis Correctional Facility gon 10. Saginaw Correctional Facility ll 11l Gratiot l l13 Carson City Correctional Facility 8 St. Clair 11. Genesee Lapeer ll Shia- 12. Richard A. Handlon Correctional Facility Ottawa Kent 1 Clinton wassee ll 2 Ma- 12. Ionia Correctional Facility Ionia comb 12. Michigan Reformatory Living- Oakland 14l ston 12. Bellamy Creek Correctional Facility Ingham Allegan Barry Eaton 13. Thumb Correctional Facility 15l 1 . Macomb Correctional Facility 4 l1 ll2 Woodland Center Correctional Facility ll 7 1 15. Van Buren Kala- ll16 Washtenaw Wayne Calhoun l1 16. G. Robert Cotton Correctional Facility mazoo Jackson 8 16. Charles E. Egeler Reception Guidance Center* Lenawee Monroe 16. Parnall Correctional Facility St. 19l l Cass Joseph Hillsdale 16. -

Corrections Quiz 14 NCIA Conference 14 Snapshots 15 Seen on Social Media 15 Corrections in the News 15 New Hires 16 Retirements 18

Corrections Connection Volume 31, Issue 5 May/June 2019 Corrections Connection May/June 2019 2 In this issue: Guardians of the Flame 3 Employee Wellness Program 5 Field Days Podcast 5 Strategic Plan 6 LARA partnership 7 Gulick named deputy director 7 Flag dedication 7 Employee Rec Day 8 Committed to community 10 Officer’s son goes pro 10 Family orientation 10 With Thanks 11 The Extra Mile 12 COPS Day 13 Thank You vets 13 Corrections Quiz 14 NCIA conference 14 Snapshots 15 Seen on social media 15 Corrections in the news 15 New hires 16 Retirements 18 Corrections Connection is a publication of the The image on the cover was taken near Onaway, Mich.- by Office of Public Information and Communications. Joe Crawley, a corrections officer at Saginaw Correctional Story ideas, feedback and comments can Facility. be submitted to Holly Kramer at KramerH@ For the chance to have your photo featured on the cover of michigan.gov. the newsletter, email a high-resolution version of the image Like MDOC on Facebook or follow us on Twitter. and a description of where it was taken to Holly Kramer at [email protected]. Committed to Protect, Dedicated to Success Corrections Connection May/June 2019 3 Guardians of the FLAME MDOC staff are key and his family look forward to each year. “One of the most enjoyable things related to my supporters of the Law job is coming out to support the Special Olympics athletes,” said Fausak, who was planning to bring Enforcement Torch Run his son to help volunteer at the Special Olympics Summer Games. -

MDE E-Rate 2019 NSLP Report

Michigan Department of Education E-Rate 2019 NSLP Report Students Annex Eligible for Total Name (DO Free Percentage Students in NOT ENTER /Reduced of Directly School District School DATA IN Meals Total Certified eligible for Percent Total Entity District NSLP % Entity COLUMNS (NSLP Students Students NSLP NSLP Number District Entity Name (Calculated) Number School Entity Name NCES Code I-N) Count) Enrolled CEP Base Year for CEP (Calculated) (Calculated) 16046621 ACE Academy (SDA) 100.00% 16046621 ACE Academy (SDA) -Glendale, Lincoln, Woodward 260094307776 224 224 224 100.00% 16046621 ACE Academy (SDA) 100.00% ACE Academy - Jefferson site 260094308800 11 11 11 100.00% 54107 AGBU Alex-Marie Manoogian School 58.96% 54107 AGBU Alex-Marie Manoogian School 260010600688 237 402 237 58.96% 16071890 Academic and Career Education Academy 78.36% 16071890 Academic and Career Education Academy 260033004509 105 134 105 78.36% 54366 Academy for Business and Technology 100.00% 16057019 Academy for Business and Technology Elementary 260016601667 255 264 2019 79.50% 264 100.00% 54366 Academy for Business and Technology 100.00% 54366 Academy for Business and Technology High School 260016601035 226 259 2019 79.50% 259 100.00% 16039853 Academy of Warren 100.00% 16039853 Academy of Warren 260030801884 636 652 2019 85.45% 652 100.00% 16058986 Achieve Charter Academy 15.34% 16058986 Achieve Charter Academy 260096307974 118 769 118 15.34% 131790 Adams Township School District 54.34% 58616 Jeffers High School 260189003921 130 250 130 52.00% 131790 Adams Township -

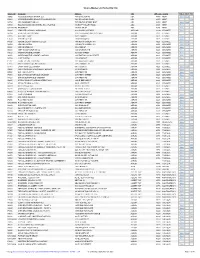

Source Master List Sorted by City

Source Master List Sorted By City Source ID Company Address City ZIP Code County Other* ROP PTI A2402 ACCESS BUSINESS GROUP, LLC 7575 E FULTON RD ADA 49355 KENT View View P0469 ACCESS BUSINESS GROUP-SPAULDING PLAZA 5101 SPAULDING PLAZA ADA 49355 KENT View N1784 ADA COGENERATION LLC 7575 FULTON STREET EAST ADA 49355 KENT View View N5183 HALLIDAY SAND AND GRAVEL, INC. - PLANT #4 866 EGYPT VALLEY ROAD ADA 49301 KENT View U411702145 RESIDENCE 645 ADA DR SE ADA 49341 KENT View B5921 LENAWEE CO ROAD COMMISSION 9293 ROUND LAKE HWY ADDISON 49220 LENAWEE View N7389 A & A CUSTOM CRUSHING GREEN HIGHWAY AND IVES ROAD ADRIAN 49221 LENAWEE View B2285 ACE DRILL CORP 2600 E MAUMEE ADRIAN 49221 LENAWEE View E8510 ADRIAN COLLEGE 110 S MADISON ST ADRIAN 49221 LENAWEE View P0426 ADRIAN ENERGY ASSOCIATES LLC 1900 NORTH OGDEN HWY ADRIAN 49221 LENAWEE View View N2369 ADRIAN LANDFILL 1970 NORTH OGDEN HWY ADRIAN 49221 LENAWEE View View B2288 ADRIAN STEEL CO 906 JAMES ST ADRIAN 49221 LENAWEE View B2289 AGET MANUFACTURING CO 1408 CHURCH ST E ADRIAN 49221 LENAWEE View N0629 ANDERSON DEVELOPMENT 525 GULF STREET ADRIAN 49221 LENAWEE View A2851 ANDERSON DEVELOPMENT COMPANY 1415 EAST MICHIGAN STREET ADRIAN 49221 LENAWEE View View N3196 CLIFT PONTIAC 1115 S MAIN ST ADRIAN 49221 LENAWEE View P1187 CORNERSTONE CRUSHING 1001 OAKWOOD ROAD ADRIAN 49221 LENAWEE View E8117 DAIRY FARMERS OF AMERICA INC 1336 E MAUMEE ST ADRIAN 49221 LENAWEE View B1754 ERVIN AMASTEEL DIVISION 915 TABOR ST. ADRIAN 49221 LENAWEE View View B2621 FLOYD’S RIGGING & MACHINERY MOVERS 831 DIVISION ST ADRIAN 49221 LENAWEE View B7068 GMI - HMA PLANT 19 2675 TREAT RD ADRIAN 49221 LENAWEE View View P0931 GMI CAT RDS-20 PORTABLE CRUSHER 2675 TREAT STREET ADRIAN 49221 LENAWEE View View N8221 GMI EXCEL PORTABLE CRUSHER 2675 TREAT RD ADRIAN 49221 LENAWEE View View B6027 INTEVA PRODUCTS ADRIAN OPERATIONS 1450 E. -

ED422966.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 422 966 IR 057 168 TITLE Directory of Michigan Libraries, 1998-1999. INSTITUTION Michigan Library, Lansing. PUB DATE 1999-00-00 NOTE 164p.; Supersedes earlier editions, see ED 418 733, ED 403 885, and ED 390 429. AVAILABLE FROM Library of Michigan, Public Information Office, P.O. Box 30007, Lansing, MI 48909. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Directories/Catalogs (132) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Academic Libraries; Branch Libraries; Depository Libraries; Elementary Secondary Education; Higher Education; *Libraries; Library Associations; Library Networks; *Library Services; Public Libraries; Regional Libraries; Special Libraries; State Libraries IDENTIFIERS *Michigan ABSTRACT This directory provides information about various types of Michigan libraries. The directory is divided into 14 sections: (1) "Alphabetical List of Public and Branch Libraries Whose Names do Not Indicate Their Location"; (2) "Public and Branch Libraries"; (3) "Library Cooperatives"; (4) "Academic Libraries"; (5) "Regions of Cooperation"; (6) "Regional Educational Media Centers"; (7) "Regional and Subregional Libraries"; (8) "Michigan Documents Depository Libraries";(9) "Federal Documents Depository Libraries";(10) "Michigan State Agency Libraries"; (11) "Special Libraries";(12) "Library Associations";(13) "School Libraries"; and (14) "Directory Update Form." Alphabetized in some sections by city and in some sections by title of organization, each entry includes address, phone and fax numbers, and a contact name, which is most often a director. For many of the listings, telecommunications-device-for-the-deaf (TDD) number, and electronic mail addresses are offered as well. Hours of operation are provided for public libraries and branch libraries. For many of the academic library listings, Web sites are included. Functioning as a search aid, an introductory section features cross-references to city or town listings from many public library names that do not mention or describe the library's location. -

Michigan Department of Corrections

MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS “Committed to Protect, Dedicated to Success” FY2022 FIVE YEAR ASSESSMENT PLAN SUMMARY The mission of the Michigan Department of Corrections is to create a safer Michigan by holding offenders accountable while promoting their success. The following is the Michigan Department of Corrections Five Year Plan Summary. This plan includes MDOC project priorities for 29 Correctional Facilities currently open and in full operation. This list encompasses prisons that have been in service since 1889 (Marquette Branch Prison) to the newest prison built in 2001 (Bellamy Creek Correctional Facility). These 29 open facilities consisting of 1,044 buildings equaling 5.658 million square feet sitting on 4,502 acres. The MDOC must provide a full range of services similar to a small community. These prison complexes must function in a safe and secure manner to ensure public, staff and prisoner safety 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, 365 days a year. In addition to the operational sites, MDOC is responsible for maintaining closed facilities. This group of closed facilities consists of 305 buildings equaling 4.8 million square feet on an additional 1,645 acres. The MDOC Physical Plant Division with assistance from a large group of Physical Plant Supervisors conduct annual assessments of all Facilities using standardized assessment processes. All available staff who possess the appropriate expertise participate in this process to ensure a diverse skill set, participate in the study and to ensure quality results. Each of our facilities is similar to a small city where prisoners are provided shelter, clothing, health care, psychological care, education, recreation, and religious needs. -

Solitary Confinement in Michigan's Prisons

MICHIGAN’S HELL LONG-TERM SENTENCES &SOLITARY CONFINEMENT If Michigan were a country, it would incarcerate more people per capita than every country on the planet except one—the United States. Michigan’s per capita incarceration rate of 641 out of every 100,000 residents far exceeds that of Cuba (510), Russia (413), Iran (284), and China (118).1 Of even greater significance is the racial disproportionality that exists in prison populations. Racialized mass incarceration is systemic, and it affects the criminal justice system at every level. Even the police, who are essentially gatekeepers to the criminal justice system, can play a considerable role in the size and composition of prison populations. Racial profiling and racially targeted patrolling can have implications for the racial composition of prison populations. Arrests, aggressive prosecution, inadequate defense, harsh sentencing, increasingly punitive parole legislation, and an inactive parole board have together expanded Michigan’s prison population since the 1970s. This has strained prison resources, reduced rehabilitative programming and contributed to a growing sense of insecurity among those currently serving time in Michigan state prisons. There are many concerns related to the conditions of prisoners’ confinement and the length of prison stays, and important advocacy concerning these issues appropriately focuses on law, legislation and policy. This report will hopefully expand the consideration of these issues into a different dimension by giving primary attention to the personal circumstances and stories of prisoners who have endured the horrors and indignity of solitary confinement and prisoners who are trapped in long-term prison sentences. This report was made possible by a grant from the Vital Projects Fund. -

Michigan Department of Corrections Correctional Facilities Map As of October 1, 2016 MSI Janitorial Service Territories

Michigan Department of Corrections Correctional Facilities Map As of October 1, 2016 MSI Janitorial Service Territories Kewee- naw Houghton 2 Ontonagon Baraga Gogebic 3 Luce Marquette 4 5 Chippewa 1 Alger Schoolcraft 6 Iron Mackinac Dickinson Delta Emmet Cheboy- Menom- gan inee Correctional Facilities NORTHERN REGION Presque Isle Charlevoix Service Tech - Alpena Mike Osiecki Otsego Mont- [email protected] Antrim morency Phone: (734) 449-3910 Leelanau Grand Oscoda Alcona Benzie Traverse Kalkaska 1. Ojibway Correctional Facility 7 Crawford 2. Baraga Correctional Facility Ogemaw Iosco 3. Marquette Branch Prison* Manistee Wexford Missau- Roscom- 4. Alger Correctional Facility 8 kee mon 5. Newberry Correctional Facility Arenac 6. Chippewa Correctional Facility Mason Lake Osceola Clare Gladwin 6. Kinross Correctional Facility Huron 7 Pugsley Correctional Facility Midland Bay 8. Oaks Correctional Facility Mecosta Isabella Tuscola Oceana 11. St. Louis Correctional Facility Neway- go Sanilac 12. Saginaw Correctional Facility 11 12 Muske- Saginaw gon Gratiot Service Tech - Mike Osiecki [email protected] 9 Phone: (734) 449-3910 Montcalm 10 9. Earnest C. Brooks Correctional Facility 14 St. Clair 9. West Shoreline Correctional Facility Genesee Lapeer Shia- Ottawa Kent Clinton wassee 10 Carson City Correctional Facility 13 Ma- 11. Central Michigan Correctional Facility Ionia comb Living- Oakland 15 13. Richard A. Handlon Correctional Facility ston Ingham 13. Ionia Correctional Facility Allegan Barry Eaton 20 13. Michigan Reformatory 18 13. Bellamy Creek Correctional Facility 17 14. Thumb Correctional Facility Van Buren Kala- 16 Washtenaw Wayne Calhoun 19 15. Macomb Correctional Facility1 mazoo Jackson 16. G. Robert Cotton Correctional Facility Lenawee Monroe 16. Charles E. Egeler Reception Guidance Center* St. -

Michigan National Guard to Aid Michigan Department of Corrections with COVID-19 Testing

EX-201 (01/2019) MICHIGAN STATE POLICE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE For more information contact: No. 190 – May 2, 2020 MDOC: Chris Gautz, 517-256-3790 MDVA: Capt. Andrew Layton, 517-940-0881 Michigan National Guard to aid Michigan Department of Corrections with COVID-19 testing LANSING, MICH. Beginning Monday at the Baraga Correctional Facility, medical specialists from the Michigan National Guard will assist Michigan Department of Corrections (MDOC) staff in testing every prisoner at the facility. The guard members will then move east across the U.P. with the goal of testing one facility each day. “The medical professionals of the Michigan National Guard are proud to assist with COVID-19 testing in the Upper Peninsula,” said Maj. Gen. Paul Rogers, adjutant general and director of the Michigan Department of Military and Veterans Affairs. “We are community members and neighbors, and we always ready to assist in the fight against COVID-19.” After Baraga, the facilities being tested include Alger Correctional Facility, Marquette Branch Prison, Newberry Correctional Facility, Chippewa Correctional Facility and Kinross Correctional Facility. All prisoners will be tested, totaling about 7,500 prisoners. “We are very grateful for the support from the National Guard in this effort to continue our testing of prisoners across the state,” said MDOC Director Heidi Washington. “Their assistance will allow us to accelerate our plans for testing our population, which will help us keep our staff, prisoners and the public safe.” The majority of the soldiers working on this project are residents of the U.P. MDOC employees who are active members of the Guard at these facilities will also assist in the process.