Program Notes: Vienna Notes on the Program by Patrick Castillo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

With a Rich History Steeped in Tradition, the Courage to Stand Apart and An

With a rich history steeped in tradition, the courage to stand apart and an enduring joy of discovery, the Wiener Symphoniker are the beating heart of the metropolis of classical music, Vienna. For 120 years, the orchestra has shaped the special sound of its native city, forging a link between past, present and future like no other. In Andrés Orozco-Estrada - for several years now an adopted Viennese - the orchestra has found a Chief Conductor to lead this skilful ensemble forward from the 20-21 season onward, and at the same time revisit its musical roots. That the Wiener Symphoniker were formed in 1900 of all years is no coincidence. The fresh wind of Viennese Modernism swirled around this new orchestra, which confronted the challenges of the 20th century with confidence and vision. This initially included the assured command of the city's musical past: they were the first orchestra to present all of Beethoven's symphonies in the Austrian capital as one cycle. The humanist and forward-looking legacy of Beethoven and Viennese Romanticism seems tailor-made for the Symphoniker, who are justly leaders in this repertoire to this day. That pioneering spirit, however, is also evident in the fact that within a very short time the Wiener Symphoniker rose to become one of the most important European orchestras for the premiering of new works. They have given the world premieres of many milestones of music history, such as Anton Bruckner's Ninth Symphony, Arnold Schönberg's Gurre-Lieder, Maurice Ravel's Piano Concerto for the Left Hand and Franz Schmidt's The Book of the Seven Seals - concerts that opened a door onto completely new worlds of sound and made these accessible to the greater masses. -

Proton Nmr Spectroscopy

1H NMR Spectroscopy (#1c) The technique of 1H NMR spectroscopy is central to organic chemistry and other fields involving analysis of organic chemicals, such as forensics and environmental science. It is based on the same principle as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). This laboratory exercise reviews the principles of interpreting 1H NMR spectra that you should be learning right now in Chemistry 302. There are four questions you should ask when you are trying to interpret an NMR spectrum. Each of these will be discussed in detail. The Four Questions to Ask While Interpreting Spectra 1. How many different environments are there? The number of peaks or resonances (signals) in the spectrum indicates the number of nonequivalent protons in a molecule. Chemically equivalent protons (magnetically equivalent protons) give the same signal in the NMR whereas nonequivalent protons give different signals. 1 For example, the compounds CH3CH3 and BrCH2CH2Br all have one peak in their H NMR spectra because all of the protons in each molecule are equivalent. The compound below, 1,2- dibromo-2-methylpropane, has two peaks: one at 1.87 ppm (the equivalent CH3’s) and the other at 3.86 ppm (the CH2). 1.87 1.87 ppm CH 3 3.86 ppm Br Br CH3 1.87 ppm 3.86 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 2. How many 1H are in each environment? The relative intensities of the signals indicate the numbers of protons that are responsible for individual signals. The area under each peak is measured in the form of an integral line. -

Dec 21 to 27.Txt

CLASSIC CHOICES PLAYLIST Dec. 21 - 27, 2020 PLAY DATE: Mon, 12/21/2020 6:02 AM Antonio Vivaldi Concerto, Op. 3, No. 10 6:12 AM TRADITIONAL Gabriel's Message (Basque carol) 6:17 AM Francisco Javier Moreno Symphony 6:29 AM Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber Sonata No.4 6:42 AM Johann Christian Bach Sinfonia Concertante for Violin, Cello 7:02 AM Various In dulci jubilo/Wexford Carol/N'ia gaire 7:12 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Piano Sonata No. 7 7:30 AM Georg Philipp Telemann Concerto for Trumpet and Violin 7:43 AM Franz Joseph Haydn Concerto 8:02 AM Henri Dumont Magnificat 8:15 AM Johann ChristophFriedrich Bach Oboe Sonata 8:33 AM Franz Krommer Concerto for 2 Clarinets 9:05 AM Joaquin Turina Sinfonia Sevillana 9:27 AM Philippe Gaubert Three Watercolors for Flute, Cello and 9:44 AM Ralph Vaughan Williams Fantasia on Christmas Carols 10:00 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Prelude & Fugue after Bach in d, 10:07 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Piano Sonata No. 9 10:25 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony No. 29 10:50 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Prelude (Fantasy) and Fugue 11:01 AM Mily Balakirev Symphony No. 2 11:39 AM Georg Philipp Telemann Overture (suite) for 3 oboes, bsn, 2vns, 12:00 PM THE CHRISTMAS REVELS: IN CELEBRATION OF THE WINTER SOLSTICE 1:00 PM Richard Strauss Oboe Concerto 1:26 PM Ludwig Van Beethoven String Quartet No. 9 2:00 PM James Pierpont Jingle Bells 2:07 PM Julius Chajes Piano Trio 2:28 PM Francois Devienne Symphonie Concertante for flute, 2:50 PM Antonio Vivaldi Concerto, "Il Riposo--Per Il Natale" 3:03 PM Zdenek Fibich Symphony No. -

Composed for Six-Hands Piano Alti El Piyano Için Bestelenen

The Turkish Online Journal of Design, Art and Communication - TOJDAC ISSN: 2146-5193, April 2018 Volume 8 Issue 2, p. 340-363 THE FORM ANALYSIS OF “SKY” COMPOSED FOR SIX-HANDS PIANO Şirin AKBULUT DEMİRCİ Assoc. Prof. Education Faculty, Music Education Faculty. Uludag University, Turkey https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8904-4920 [email protected] Berkant GENÇKAL Assoc. Prof. State Conservatory, School for Music and Drama. Anadolu University, Turkey https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5792-2100 [email protected] ABSTRACT The piano, which is a solo instrument that takes part in educational process, can take role not only in instrumental education but also in chamber music education as well with the 6-hands pieces for three players that perform same composition on a single instrument. According to the international 6-hands piano literature, although the works of Alfred Schnittke's Hommage, Carl Czerny's Op.17 and 741, Paul Robinson's Pensees and Montmartre and many more are included, the Turkish piano literature has been found to have a limited number of compositions. The aim of the work is to contribute to the field by presenting musical analysis about the place and the importance of the educational use of the works composed for 6-hands which are extremely rare in the Turkish piano literature. As an example, the piece named Sky composed by Hasan Barış Gemici is considered. Analysis is supported by comparative methods in form, structuralism, rhythm, theoretical applications and performance; it also gives information about basic playing techniques. It is thought that this study carries importance in contributing to the limited number of Turkish 6-hands piano literature and researchers who will conduct research in this regard, in terms of creating resources for performers and composers who will interpret the literature. -

The Tuesday Concert Series at Tuesday Maintain Epiphany’S Artistic Profile the Church of the Epiphany and Its Instruments

the HOW YOU CAN CONSIDER HELPING THE TUESDAY CONCERT SERIES AT TUESDAY MAINTAIN EPIPHANY’S ARTISTIC PROFILE THE CHURCH OF THE EPIPHANY AND ITS INSTRUMENTS CONCERT The Tuesday Concert Series reaches out to the entire metropolitan Washington community 52 weeks of the year, and Since the Church of the Epiphany was founded in brings both national and international artists here to 1842, music has played a vital role in the life of the parish. The Tuesday Concert Series reaches out to the SERIES Washington, DC. The series enjoys partnerships with many entire metropolitan Washington community and runs artistic groups in the area, too, most keenly with the Washington throughout the year. No other concert series follows July - December Bach Consort, the Levine School of Music, and the Avanti such a pattern and, as such, it is unique in the 2017 Orchestra. Washington, DC area. There is no admission charge to the concerts, and visitors and Epiphany houses three fine musical instruments: The regular concert-goers are invited to make a freewill offering to Steinway D concert grand piano was a gift to the support our artists. This freewill offering has been the primary church in 1984, in memory of vestry member Paul source of revenue from which our performers have been Shinkman, and the 4-manual, 64-rank, 3,467-pipe remunerated, and a small portion of this helps to defray costs of Æolian-Skinner pipe organ (1968) is one of the most the church’s administration, advertising and instrument upkeep. versatile in the city. The 3-stop chamber organ (2014), Today, maintaining the artistic quality of Epiphany’s series with commissioned in memory of Albert and Frances this source of revenue is challenging. -

Grandview Graduation Performances Archive

Grandview Graduation Performances Archive 2020 Graduation Speech-“We did it” “Landslide” by Stevie Nicks (Vocal Solo) 2019 A Graduation Skit-Comedy Sketch “No Such Thing” by John Mayer (Guitar/Vocal Duet) “See You Again” by Wiz Khalifa and Charlie Puth (Instrumental Duet) “Journey to the Past” by Stephen Flaherty (Vocal Solo) “I Lived a Good Life Gone” by One Republic and Phillip Phillips (Vocal Octet) 2018 Graduation Speech-“A Poem” “You Will Be Found” by Benj Pasek and Justin Paul (Vocal Octet) “Bring It On Home To Me” by Sam Cooke (Instrumental Sextet) “This Is Me” by Benj Pasek and Justin Paul (Vocal Solo w/support from Senior Choir) 2017 Adoration for Violin and Piano Duet by Felix Borowski Graduation Speech-“Single” “Fools Who Dream” by Justin Hurwitz and Benj Pasek (Vocal Duet) Original Number-Down to the Wire for Piano and Saxphone “From the First Hello to the Last Goodbye” by Johnny Burke (Vocal Octet) 2016 “As If We Never Said Goodbye” by Don Black, Christopher Hampton & Andrew Lloyd Weber (Solo with Piano accompaniment) Rondo from Sonata No. 3 for Violin and Piano Duet by Ludwig van Beethoven (Violin and Piano) Graduation Speech –Pair Graduation Speech-Trio “I Lived” Ryan Tedder and Noel Zancanella Orchestra Octet and 2 Vocalists) 2015 Clarinet and Bassoon Duet 3 by Ludwig van Beethoven “My Wish” by Steele and Robson “Corner of the Sky” from Pippin by Stephen Schwartz 2014 Even if your Heart Breaks by Hoge and Paslay Never Give up, Never Surrender (a speech) by Malik Williams Meditation from Thais by Massenet (Violin and piano) Take Chances by Nelson 2013 Come Fly with Me (Vocalist and piano) Moderato by Kummer (Wood wind Duet) Homeward Bound (Vocalist and Piano) Live your Life by Yuna (Vocalist and guitar accompaniment) 2012 You Raise Me Up (Violins/Cello Trio) Who I’d Be (Male Vocal Solo, Recorded Accompaniment) 1 Grandview Graduation Performances Archive Crazy Dreams (Female/Male Vocal, Guitar Accompaniment) Transcendental etude No. -

Download Program Notes

Notes on the Program By James M. Keller, Program Annotator, The Leni and Peter May Chair Piano Quintet in F minor, Op. 34 Johannes Brahms ohannes Brahms was 29 years old in 1862, seated at the other piano. Ironically, critics Jwhen he embarked on this seminal mas- now complained that the work lacked the terpiece of the chamber-music repertoire, sort of warmth that string instruments would though the work would not reach its final have provided — the opposite of Joachim’s form as his Piano Quintet until two years objection. Unlike the original string-quintet later. He was no beginner in chamber music version, which Brahms burned, the piano when he began this project. He had already duet was published — and is still performed written dozens of ensemble works before and appreciated — as his Op. 34bis. he dared to publish one, his B-major Piano By this time, however, Brahms must have Trio (Op. 8) of 1853–54. Among those early, grown convinced of the musical merits of his unpublished chamber pieces were 20-odd material and, with some coaxing from his string quartets, all of which he consigned friend Clara Schumann, he gave the piece to destruction prior to finally publishing his one more try, incorporating the most idiom- three mature works in that classic genre in atic aspects of both versions. The resulting the 1870s. In truth, he did get some use out Piano Quintet, the composer’s only essay of those early quartets — to paper the walls in that genre (and no wonder, after all that and ceilings of his apartment. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 42,1922

PARSONS THEATRE . ,. HARTFORD Monday Evening, November 27, at 8.15 .-# BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHCSTRS INC. FORTY-SECOND SEASON J922-J923 wW PRSGRsnnc 1 vg LOCAL MANAGEMENT, SEDGWICK & CASEY Steinway & Sons STEINERT JEWETT WOODBURY «. PIANOS w Duo-Art REPRODUCING PIANOS AND PIANOLA PIANOS VICTROLAS VICTOR RECORDS M, STEINERT & SONS 183 CHURCH STREET NEW HAVEN PARSONS THEATRE HARTFORD FORTY-SECOND SEASON 1922-1923 INC. PIERRE MONTEUX, Conductor MONDAY EVENING, NOVEMBER 27, at 8.15 WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE COPYRIGHT, 1922, BY BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, INC. THE OFFICERS AND TRUSTEES OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. FREDERICK P. CABOT President GALEN L. STONE Vice-President ERNEST B. DANE Treasurer ALFRED L. AIKEN ARTHUR LYMAN FREDERICK P. CABOT HENRY B. SAWYER ERNEST B. DANE GALEN L. STONE M. A. DE WOLFE HOWE BENTLEY W. WARREN JOHN ELLERTON LODGE E. SOHIER WELCH W. H. BRENNAN, Manager G. E. JUDD, Assistant Manager *UHE INSTRUMENT OF THE IMMORTALS QOMETIMES people who want a Steinway think it economi- cal to buy a cheaper piano in the beginning and wait for a Steinway. Usually this is because they do not realize with what ease Franz Liszt at his Steinway and convenience a Steinway can be bought. This is evidenced by the great number of people who come to exchange some other piano in partial payment for a Steinway, and say: "If I had only known about your terms I would have had a Steinway long ago!" You may purchase a new Steinway piano with a cash deposit of 10%, and the bal- ance will be extended over a period of two years. -

Spectralism in the Saxophone Repertoire: an Overview and Performance Guide

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY Spectralism in the Saxophone Repertoire: An Overview and Performance Guide A PROJECT DOCUMENT SUBMITTED TO THE BIENEN SCHOOL OF MUSIC IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS for the degree DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS Program of Saxophone Performance By Thomas Michael Snydacker EVANSTON, ILLINOIS JUNE 2019 2 ABSTRACT Spectralism in the Saxophone Repertoire: An Overview and Performance Guide Thomas Snydacker The saxophone has long been an instrument at the forefront of new music. Since its invention, supporters of the saxophone have tirelessly pushed to create a repertoire, which has resulted today in an impressive body of work for the yet relatively new instrument. The saxophone has found itself on the cutting edge of new concert music for practically its entire existence, with composers attracted both to its vast array of tonal colors and technical capabilities, as well as the surplus of performers eager to adopt new repertoire. Since the 1970s, one of the most eminent and consequential styles of contemporary music composition has been spectralism. The saxophone, predictably, has benefited tremendously, with repertoire from Gérard Grisey and other founders of the spectral movement, as well as their students and successors. Spectral music has continued to evolve and to influence many compositions into the early stages of the twenty-first century, and the saxophone, ever riding the crest of the wave of new music, has continued to expand its body of repertoire thanks in part to the influence of the spectralists. The current study is a guide for modern saxophonists and pedagogues interested in acquainting themselves with the saxophone music of the spectralists. -

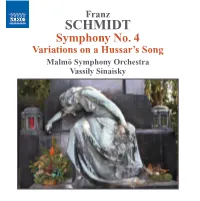

Franz Schmidt

Franz Schmidt (1874 – 1939) was born in Pressburg, now Bratislava, a citizen of the Austro- Hungarian Empire and died in Vienna, a citizen of the Nazi Reich by virtue of Hitler's Anschluss which had then recently annexed Austria into the gathering darkness closing over Europe. Schmidt's father was of mixed Austrian-Hungarian background; his mother entirely Hungarian; his upbringing and schooling thoroughly in the prevailing German-Austrian culture of the day. In 1888 the Schmidt family moved to Vienna, where Franz enrolled in the Conservatory to study composition with Robert Fuchs, cello with Ferdinand Hellmesberger and music theory with Anton Bruckner. He graduated "with excellence" in 1896, the year of Bruckner's death. His career blossomed as a teacher of cello, piano and composition at the Conservatory, later renamed the Imperial Academy. As a composer, Schmidt may be seen as one of the last of the major musical figures in the long line of Austro-German composers, from Haydn, Beethoven, Schubert, Brahms, Bruckner and Mahler. His four symphonies and his final, great masterwork, the oratorio Das Buch mit sieben Siegeln (The Book with Seven Seals) are rightly seen as the summation of his creative work and a "crown jewel" of the Viennese symphonic tradition. Das Buch occupied Schmidt during the last years of his life, from 1935 to 1937, a time during which he also suffered from cancer – the disease that would eventually take his life. In it he sets selected passages from the last book of the New Testament, the Book of Revelation, tied together with an original narrative text. -

The Virtuoso Johann Strauss

The Virtuoso Johann Strauss Thomas Labé, Piano CD CONTENTS 1. Carnaval de Vienne/Moriz Rosenthal 2. Wahlstimmen/Karl Tausig 3. Symphonic Metamorphosis of Wein, Weib und Gesang (Wine, Woman and Song)/Leopold Godowsky 4. Man lebt nur einmal (One Lives but Once)/Karl Tausig 5. Symphonic Metamorphosis of Die Fledermaus/Leopold Godowsky 6. Valse-Caprice in A Major (Op. Posth.)/Karl Tausig 7. Nachtfalter (The Moth)/Karl Tausig 8. Arabesques on By the Beautiful Blue Danube/Adolf Schulz-Evler LINER NOTES At the end of Johann Strauss’ 1875 operetta Die Fledermaus, all of the characters drink a toast to the real culprit of the story—“Champagner hat's verschuldet”—a fitting conclusion to the most renowned and potent evocation of the carefree life of post-revolution imperial Vienna. Strauss' sparkling score (never mind that the libretto is an amalgam of German and French sources), infused with that most famous of Viennese dances, the waltz, lent eloquent expression to the transitory atmosphere of confidence and prosperity induced by the Hapsburg monarchs. “The Emporer Franz Joseph I,” it would later be said, "only reigned until the death of Johann Strauss." And what could have provided more perfect source material than the music of Strauss, for the pastiche creations of the illustrious composer-pianists who roamed the world in the latter 19th and early 20th centuries, forever seeking vehicles with which to exploit the possibilities of their instrument and display their pianistic prowess? This disc presents a succession of such indulgent enterprises, all fashioned from Strauss’ music, for four notable composer-pianists: Moriz Rosenthal, Karl Tausig, Leopold Godowsky, and Adolf Schulz-Evler. -

570034Bk Hasse 23/8/10 5:34 PM Page 4

572118bk Schmidt4:570034bk Hasse 23/8/10 5:34 PM Page 4 Vassily Sinaisky Vassily Sinaisky’s international career was launched in 1973 when he won the Gold Franz Medal at the prestigious Karajan Competition in Berlin. His early work as Assistant to the legendary Kondrashin at the Moscow Philharmonic, and his study with Ilya Musin at the Leningrad Conservatory provided him with an incomparable grounding. SCHMIDT He has been professor in conducting at the Music Conservatory in St Petersburg for the past thirty years. Sinaisky was Music Director and Principal Conductor of the Photo: Jesper Lindgren Moscow Philharmonic from 1991 to 1996. He has also held the posts of Chief Symphony No. 4 Conductor of the Latvian Symphony and Principal Guest Conductor of the Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra. He was appointed Music Director and Principal Variations on a Hussar’s Song Conductor of the Russian State Orchestra (formerly Svetlanov’s USSR State Symphony Orchestra), a position which he held until 2002. He is Chief Guest Conductor of the BBC Philharmonic and is a regular and popular visitor to the BBC Malmö Symphony Orchestra Proms each summer. In January 2007 Sinaisky took over as Principal Conductor of the Malmö Symphony Orchestra in Sweden. His appointment forms part of an ambitious new development plan for Vassily Sinaisky the orchestra which has already resulted in hugely successful projects both in Sweden and further afield. In September 2009 he was appointed a ‘permanent conductor’ at the Bolshoi in Moscow (a position shared with four other conductors). Malmö Symphony Orchestra The Malmö Symphony Orchestra (MSO) consists of a hundred highly talented musicians who demonstrate their skills in a wide range of concerts.