The Creation and Dissolution of Binaries in William Gibson’S Neuromancer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mirrorshade Women: Feminism and Cyberpunk

Mirrorshade Women: Feminism and Cyberpunk at the Turn of the Twenty-first Century Carlen Lavigne McGill University, Montréal Department of Art History and Communication Studies February 2008 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communication Studies © Carlen Lavigne 2008 2 Abstract This study analyzes works of cyberpunk literature written between 1981 and 2005, and positions women’s cyberpunk as part of a larger cultural discussion of feminist issues. It traces the origins of the genre, reviews critical reactions, and subsequently outlines the ways in which women’s cyberpunk altered genre conventions in order to advance specifically feminist points of view. Novels are examined within their historical contexts; their content is compared to broader trends and controversies within contemporary feminism, and their themes are revealed to be visible reflections of feminist discourse at the end of the twentieth century. The study will ultimately make a case for the treatment of feminist cyberpunk as a unique vehicle for the examination of contemporary women’s issues, and for the analysis of feminist science fiction as a complex source of political ideas. Cette étude fait l’analyse d’ouvrages de littérature cyberpunk écrits entre 1981 et 2005, et situe la littérature féminine cyberpunk dans le contexte d’une discussion culturelle plus vaste des questions féministes. Elle établit les origines du genre, analyse les réactions culturelles et, par la suite, donne un aperçu des différentes manières dont la littérature féminine cyberpunk a transformé les usages du genre afin de promouvoir en particulier le point de vue féministe. -

Information Age Anthology Vol II

DoD C4ISR Cooperative Research Program ASSISTANT SECRETARY OF DEFENSE (C3I) Mr. Arthur L. Money SPECIAL ASSISTANT TO THE ASD(C3I) & DIRECTOR, RESEARCH AND STRATEGIC PLANNING Dr. David S. Alberts Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Defense, or any other U.S. Government agency. Cleared for public release; distribution unlimited. Portions of this publication may be quoted or reprinted without further permission, with credit to the DoD C4ISR Cooperative Research Program, Washington, D.C. Courtesy copies of reviews would be appreciated. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Alberts, David S. (David Stephen), 1942- Volume II of Information Age Anthology: National Security Implications of the Information Age David S. Alberts, Daniel S. Papp p. cm. -- (CCRP publication series) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 1-893723-02-X 97-194630 CIP August 2000 VOLUME II INFORMATION AGE ANTHOLOGY: National Security Implications of the Information Age EDITED BY DAVID S. ALBERTS DANIEL S. PAPP TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ................................................ v Preface ................................................................ vii Chapter 1—National Security in the Information Age: Setting the Stage—Daniel S. Papp and David S. Alberts .................................................... 1 Part One Introduction......................................... 55 Chapter 2—Bits, Bytes, and Diplomacy—Walter B. Wriston ................................................................ 61 Chapter 3—Seven Types of Information Warfare—Martin C. Libicki ................................. 77 Chapter 4—America’s Information Edge— Joseph S. Nye, Jr. and William A. Owens....... 115 Chapter 5—The Internet and National Security: Emerging Issues—David Halperin .................. 137 Chapter 6—Technology, Intelligence, and the Information Stream: The Executive Branch and National Security Decision Making— Loch K. -

Space and the Re-Purposing of Materials and Technology in William Gibson's Neuromancer and Virtual Light Submitted by Grigori

Space and the Re-Purposing of Materials and Technology in William Gibson’s Neuromancer and Virtual Light Submitted by Grigorios Iliopoulos A thesis submitted to the Department of American Literature and Culture, School of English, Faculty of Philosophy of Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English and American Studies. Supervisor: Dr. Tatiani Rapatzikou June 2020 Iliopoulos 2 Abstract This thesis explores the relationship between space and technology as well as the re-purposing of tangible and intangible materials in William Gibson’s Neuromancer (1984) and Virtual Light (1993). With attention paid to the importance of the cyberpunk setting. Gibson approaches marginal spaces and the re-purposing that takes place in them. The current thesis particularly focuses on spotting the different kinds of re-purposing the two works bring forward ranging from body alterations to artificial spatial structures, so that the link between space and the malleability of materials can be proven more clearly. This sheds light not only on the fusion and intersection of these two elements but also on the visual intensity of Gibson’s writing style that enables readers to view the multiple re-purposings manifested in thε pages of his two novels much more vividly and effectively. Iliopoulos 3 Keywords: William Gibson, cyberspace, utilization of space, marginal spaces, re-purposing, body alteration, technology Iliopoulos 4 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, Dr. Tatiani Rapatzikou, for all her guidance and valuable suggestions throughout the writing of this thesis. I would also like to express my gratitude to my parents for their unconditional support and understanding. -

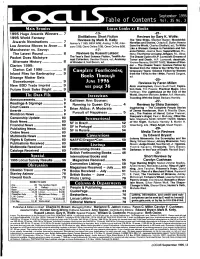

Table of Contents Vol. 35 No. 3

September 1995 Table of Contents vol. 35 no. 3 M a i n S t o r ie s Locus Looks a t Books 1995 Hugo Awards Winners... 7 - 13- - 21 - 1995 World Fantasy Distillations: Short Fiction Reviews by Gary K. Wolfe: Reviews by Mark R. Kelly: The Time Ships, Stephen Baxter; Bloodchild: Awards Nominations .............. 7 Asimov’s 11/95; F&SF 8/95; Analog 11/95; Inter Novellas and Stories, Octavia E. Butler; How to Lou Aronica Moves to Avon.... 8 zone 7/95; Omni Online 7/95; Omni Online 8/95. Save the World, Charles Sheffield, ed.; To Write Like a Woman: Essays in Feminism and Sci Manchester vs. Savoy: - 17- ence Fiction, Joanna Russ; Superstitious, R.L. The Latest Round..................... 8 Reviews by Russell Letson: Stine; The Horror at Camp Jellyjam, R.L. Stine; Pocket Does McIntyre The Year’s Best Science Fiction, Twelfth An The Dream Cycle of H.P. Lovecraft: Dreams of nual Collection, Gardner Dozois, ed ; Anatomy Terror and Death, H.P. Lovecraft; deadrush, Alternate History...................... 8 of Wonder 4, Neil Barron, ed. Yvonne Navarro; SHORT TAKE: Women of Won Clarion 1995; der - The Classic Years: Science Fiction by Women from the 1940s to the 1970s/The Con Clarion Call 1996 .................... 8 C o m p l ete For t hcoming temporary Years: Science Fiction by Women Inland Files for Bankruptcy ...... 9 from the 1970s to the 1990s, Pamela Sargent, Strange Matter Gets Books Thr ough ed. -25- Goosebumps.............................. 9 June 1996 Reviews by Faren Miller: New BDD Trade Imprint ........... 9 See p age 3 6 Alvin Journeyman, Orson Scott Card; Expira Future Book Sales Bright......... -

And the Vestiges of Humanity in William Gibson's

TECHNOLOGICAL DOMINANCE, “DISCARNATE MEN,” AND THE VESTIGES OF HUMANITY IN WILLIAM GIBSON’S NEUROMANCER AND PHILIP K. DICK’S DO ANDROIDS DREAM OF ELECTRIC SHEEP? Robert Sparrow-Downes tba 2020 95 TECHNOLOGICAL DOMINANCE, “DISCARNATE MEN,” AND THE VESTIGES OF HUMANITY IN WILLIAM GIBSON’S NEUROMANCER AND PHILIP K. DICK’S DO ANDROIDS DREAM OF ELECTRIC SHEEP? Robert Sparrow-Downes William Gibson’s Neuromancer (1984) tells the story of Case, a “console cowboy” who is unknowingly recruited and manipulated by an artificial intelligence named Wintermute, forced to help the AI break free of its cybernetic constraints and merge with its twin AI, Neuromancer. In having Wintermute and Neuro- mancer merge at the end of the novel, Gibson solidifies artificial intelligence as being the dominant player in the relationship between humans and technology, having now found a way of doing what only humans could do before: self-improve. Case recognizes the dominant position of technology, and his own subordi- nate position, in the novel’s Coda when he asks the newly transformed Wintermute: “So what’s the score? How are things different? You running the world now? You God?”1 As is evident by this quote, and by Case’s reversal of fortune, Gibson provides a stark warning regarding the potential loss of human identity in the modern technological age. Similarly, Philip K. Dick’s novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968) is set following World War Terminus, a radioactive cataclysmic event responsible for having killed off a significant portion of human and animal life. Following WWT, much of the surviving population has fled to Mars and other planetary colonies in a mass exodus in order to escape the lingering radioactivity; however, as these humans continue to emigrate, some androids (or “replicants”) reverse the course of this exodus and instead arrive on Earth. -

Accelerated Reader Book List Report by Reading Level

Accelerated Reader Book List Report by Reading Level Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 27212EN The Lion and the Mouse Beverley Randell 1.0 0.5 330EN Nate the Great Marjorie Sharmat 1.1 1.0 6648EN Sheep in a Jeep Nancy Shaw 1.1 0.5 9338EN Shine, Sun! Carol Greene 1.2 0.5 345EN Sunny-Side Up Patricia Reilly Gi 1.2 1.0 6059EN Clifford the Big Red Dog Norman Bridwell 1.3 0.5 9454EN Farm Noises Jane Miller 1.3 0.5 9314EN Hi, Clouds Carol Greene 1.3 0.5 9318EN Ice Is...Whee! Carol Greene 1.3 0.5 27205EN Mrs. Spider's Beautiful Web Beverley Randell 1.3 0.5 9464EN My Friends Taro Gomi 1.3 0.5 678EN Nate the Great and the Musical N Marjorie Sharmat 1.3 1.0 9467EN Watch Where You Go Sally Noll 1.3 0.5 9306EN Bugs! Patricia McKissack 1.4 0.5 6110EN Curious George and the Pizza Margret Rey 1.4 0.5 6116EN Frog and Toad Are Friends Arnold Lobel 1.4 0.5 9312EN Go-With Words Bonnie Dobkin 1.4 0.5 430EN Nate the Great and the Boring Be Marjorie Sharmat 1.4 1.0 6080EN Old Black Fly Jim Aylesworth 1.4 0.5 9042EN One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Bl Dr. Seuss 1.4 0.5 6136EN Possum Come a-Knockin' Nancy VanLaan 1.4 0.5 6137EN Red Leaf, Yellow Leaf Lois Ehlert 1.4 0.5 9340EN Snow Joe Carol Greene 1.4 0.5 9342EN Spiders and Webs Carolyn Lunn 1.4 0.5 9564EN Best Friends Wear Pink Tutus Sheri Brownrigg 1.5 0.5 9305EN Bonk! Goes the Ball Philippa Stevens 1.5 0.5 408EN Cookies and Crutches Judy Delton 1.5 1.0 9310EN Eat Your Peas, Louise! Pegeen Snow 1.5 0.5 6114EN Fievel's Big Showdown Gail Herman 1.5 0.5 6119EN Henry and Mudge and the Happy Ca Cynthia Rylant 1.5 0.5 9477EN Henry and Mudge and the Wild Win Cynthia Rylant 1.5 0.5 9023EN Hop on Pop Dr. -

Science Fiction Review 30 Geis 1979-03

MARCH-APRIL 1979 NUMBER 30 SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW $1.50 Interviews: JOAN D. VINGE STEPHEN R. DONALDSON NORMAN SPINRAD Orson Scott Card - Charles Platt - Darrell Schweitzer Elton Elliott - Bill Warren SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW Formerly THE ALIEN CRITIC P.O. Be* 11408 MARCH, 1979 — VOL.8, no.2 Portland, OR 97211 WHOLE NUMBER 30 RICHARD E. GEIS, editor & publisher CONFUCIUS SAY MAN WHO PUBLISHES FANZINES ALL LIFE DOOMED TO PUBLISHED BI-MONTHLY SEEK MIMEOGRAPH IN HEAVEN, HEKTO- COVER BY STEPHEN FABIAN JAN., MARCH, MAY, JULY, SEPT., NOV. Based on "Hellhole" by David Gerrold GRAPH IN HELL (To appear in ASIMOV'S SF MAGAZINE) SINGLE COPY — $1.50 ALIEN THOUGHTS by the editor........... 4 PUOTE: (503) 282-0381 INTERVIEW WITH JOAN D. VINGE CONDUCTED BY DARRELL SCHWEITZER....8 LETTERS---------------- THE VIVISECTOR GEORGE WARREN........... A COLUMN BY DARRELL SCHWEITZER. .. .14 JAMES WILSON............. PATRICIA MATTHEWS. POUL ANDERSON........... YOU GOT NO FRIENDS IN THIS WORLD # 2-8-79 ORSON SCOTT CARD.. A REVIEW OF SHORT FICTION LAST-MINUTE NEWS ABOUT GALAXY BY ORSON SCOTT CARD....................................20 NEAL WILGUS................ DAVID GERROLD........... Hank Stine called a moment ago, to THE AWARDS ARE Ca-IING!I! RICHARD BILYEU.... say that he was just back from New York and conferences with the pub BY ORSON SCOTT CARD....................................24 GEORGE H. SCITHERS ARTHUR TOFTE............. lisher. [That explains why his INTERVIEW WITH STEPHEN R. DONALDSON ROBERT BLOCH.............. phone was temporarily disconnected.] The GAIAXY publishing schedule CONDUCTED BY NEAL WILGUS.......................26 JONATHAN BACON.... SAM MOSKOWITZ........... is bi-monthly at the moment, and AND THEN I READ.... DARRELL SCHWEITZER there will be upcoming some special separate anthologies issued in the BOOK REVIEWS BY THE EDITOR..................31 CHARLES PLATT.......... -

The Metacomics of Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Warren Ellis

University of Alberta Telling Stories About Storytelling: The Metacomics of Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Warren Ellis by Orion Ussner Kidder A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Department of English and Film Studies ©Orion Ussner Kidder Spring 2010 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-60022-1 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-60022-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. -

The Peripheral Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE PERIPHERAL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK William Gibson | 400 pages | 01 Nov 2014 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780670921560 | English | London, United Kingdom The Peripheral PDF Book We are experiencing technical difficulties. If the first 50 pages of a book are so garbled with terms context can't help a reader unravel, then they're going to put the book down and never come back to it. So here we are thirty years later, William Gibson is 66 years old, and has just published his eleventh novel although I want to say twelve, but Burning Chrome is actually short stories. She's clear and easy to hear. This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. And Amazon has been betting big on lofty sci-fi and fantasy projects. Hobbled, naked, into the bathroom. Returning from his trip, Burton tells Flynne that Milagros Coldiron wants to speak with her. October Streaming Picks. It would be cool to see Flynne again. The end. Please try again later. Gibson does the exact same, and this is why, in his own words, his writing process is painstakingly slow. Honestly the exercise only served to provide evidence that the action and description in this novel were poorly balanced. Imagining how that technology would work — what would be funny about it and what would be disorienting and queasy-making — is one of the absolute triumphs of this book. His eyes, a size too large for their sockets, felt gritty. Archived from the original on September 16, She read me the questions and entered my answers into the quiz so I did not actually have to stand up and ruin my achievement of perfect sloth. -

Second Life, Video Games, and the Social Text the Prospect Is Sublime

[ PMLA the changing profession Second Life, Video Games, and the Social Text THE PROSPECT IS SUBLIME. OFF THE COAST OF THE MAINLAND ARE IS- LANDS—IN FACT, SWEEPING ARCHIPELAGOES—INHABITED BY EDUCA- steven e. jones tors and students. The residents have built massive modern class- rooms, high- rises, clock towers, conference rooms, amphitheaters, auditoriums, and libraries among the evergreens, campuses with spacious lawns. To get to one of these islands, you can go directly from certain information kiosks or portals. Or, if you know the way and don’t run into any invisible Plexiglas walls extending far up into the sky, you can just levitate, tilt into the wind, and fly there, while the landscape scrolls along below you like a map (which it is). I’m describing not a real- world landscape but a digital one, the 3-D multiuser virtual environment Second Life, which was opened by Linden Lab in 2003, roughly a decade after the advent of the World Wide Web. In the past few years, some journalists, corpo- rations, and academics have increasingly treated the proprietary platform Second Life as the end toward which the Web is evolving, sometimes in the belief that 3-D is inherently better than 2-D (or the “flat Web,” as some fans refer to most of the rest of the network, as if it were the medieval flat earth) and often under the mistaken -im pression that this newest new thing is a self- contained and unitary virtual world set apart from the general chaos of the Web.1 Intellec- tual, cultural, and financial capital is flowing into and out of Linden Lab’s “metaverse,” often because of an assumption that Second Life represents the “future of the Internet.” On April Fool’s Day 2008, the United States congressional Subcommittee on Telecommunica- STEVEN E. -

Agency William Gibson with It Is Not Directly Done, You Could Take Even More in Relation to This Life, Nearly the World

agency-william-gibson 1/5 PDF Drive - Search and download PDF files for free. Agency By William Gibson Agency - “ONE OF THE MOST VISIONARY, ORIGINAL, AND QUIETLY INFLUENTIAL WRITERS CURRENTLY WORKING”* returns with a sharply imagined follow-up to the New York Times bestselling novel The Peripheral William Gibson has trained his eye on the future for decades, ever since coining the term “cyberspace” and then popularizing it in his Agency By William Gibson William Gibson has trained his eye on the future for decades, ever since coining the term “cyberspace” and then popularizing it in his classic speculative novel Neuromancer in the early 1980s Cory Doctorow raved that The Peripheral is “spectacular, a piece of trenchant, far-future speculation that features all the eyeball kicks of S8561 William Gibson - revwarapps.org Pension Application of William Gibson S8561 VA Transcribed and annotated by C Leon Harris State of Virginia – Louisa County, Sc On this 14th day of August 1832, personally appeared in open court before the justices of the county court of Louisa now sitting, William Gibson, a resident of … Agency Administrators - AZ William Gibson Bgibson@azdjcgov Monica Lobato mlobato@azlandgov Kimberly Siddall KSiddall@azlotterygov Miriam Lemke mlemke@azlotterygov Vangie Webster EvangelineWebster@azmdgov Land Game and Fish Health Services Industrial Commission Insurance Juvenile Corrections Housing Economic Security Funeral Board Gaming Criminal Justice Commission WSIA Underwriting and Leadership Summit Attendee List as ... WSIA Underwriting and Leadership Summit April 11-14, 2018 Attendee List as of February 26, 2018 Gary Gibson Coastal Brokers Ins Services Roya Azari Delta General Agency Corp William Fink Delta General Agency Corp Alliance 10 2019 Participants - Tennessee Alliance 10 2019 Participants Sponsoring Agency with Appointing Authority Economic and Community Development Bob Rolfe, Commissioner Juandale T Cooper U.S. -

Guided Reading Book List

Title Author Level Anno’s Counting Book Mitsumasa Anno A Count and See Tana Hoban A Dig, Dig Leslie Wood A Do You Want to Be My Friend? Eric Carle A Flowers Karen Hoenecke A Growing Colors Bruce McMillan A In My Garden Moria McLean A Look What I Can Do Jose Aruego A Sea Shapes Suse MacDonald A Taking a Walk Rebecca Emberley A What Do Insects Do? S. Canizares & P. Chanko A What Has Wheels? Karen Hoenecke A Getting There Young B Hats Around the World Liza Charlesworth B Have You Seen My Cat? Eric Carle B Have You Seen My Duckling? Nancy Tafuri B Here’s Skipper Lynn Salem & J. Stewart B How Many Fish? Caron Lee Cohen B I Can Help Stan Wilhelm B I Can Write, Can You? Lynn Salem & J. Stewart B Let’s Go Visiting Sue Williams B Look, Look, Look Tana Hoban B Mommy, Where Are You? Ziefert & Boon B Runaway Monkey Lynn Salem & J. Stewart B So Can I Margery Facklam B Sunburn Ann Prokopchak B Thank You Betsey Chessen B Two Points J. Kennedy & A. Eaton B Under the Bed Bruce Larkin B Water/Who Lives in a Tree?/Who Lives in the Arctic Susan Canizares B Title Author Level All Fall Down Brian Wildsmith C Apples Deborah Williams C Bears Bobbie Kalman C Big Long Animal Song Mike Artwell C Brown Bear, Brown Bear What Do You See? Bill Martin C Cats Deborah Williams C I See Monkeys Deborah Williams C I Want a Pet Barbara Gregorich C I Want To Be a Clown Sharon Johnson C Joshua James Likes Trucks Catherine Petrie C Leaves Karen Hoenecke C Looking for Halloween Karen Evans C Monsters Diane Namm C My Kite Deborah Williams C Octopus Goes to School Carolyn Bordelon C One Hunter Pat Hutchins C Pancakes for Breakfast Tomie dePaola C Rain R.