University of Huddersfield Repository

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summerhill 11-01-11.Pmd

The Middle Class in India: An Overview RITA KOTHARI Sai Paranjapeís acclaimed film Katha (1983) shows the Indians. Hailing from small towns (Bunty aur Babli, 2005), protagonist Rajaram Pushottam Joshi living in a chawl or ëoldí middle-class families in Bombay (Rangeela, 1995) in Bombay in India of the 1980s. Dressed in a half-sleeved and Delhi (Oye Lucky! Lucky Oye!, 2008) and (Khosla Ka shirt and slightly shapeless trousers, he missed his first Ghosla, 2006). Raring to redefine themselves, they bus to work almost every single day. The city transport represent the expanding middle class. Shedding what bus required a passenger to muscle his way on board, they do not want (clerical jobs, restrictive circumstances) brutally elbowing aside anyone who got in the way. But and eagerly embracing all that India after liberalisation Rajaram was constrained by his own norms of civility had to offer (money, the English language, brand names, and fairness. So he got left behind at the bus stop, along career opportunities) they stand out by their desire to with an old toothless woman ó two timorous souls who do well.1 would not, or could not summon up the aggression and The class they represent is ëthe darling of the official ruthlessness demanded by metropolitan life. discourse and policy makersíand one that ësets the terms The visual imagery returns to the spectator as Rajaram of reference of Indian societyí (Jaffrelot and Van der Veer, goes through several comic-tragic travails; the mockery 2008 : 19). In the city of Ahmedabad where I live, this he evokes by putting up a Hindi (not English) name-plate class is the addressee for whom the new flyovers are on his door, his ineptness at wooing a girl or an built, and hoardings announcing posh houses with employer, and his overall belief that it was alright to attributes such as ëreal auraí and ëtruly eliteí and ësheer live in middle-class housing. -

Sovereignty and Social Change in the Wake of India's Recent Sodomy Cases

Alabama Law Scholarly Commons Articles Faculty Scholarship 2017 Sovereignty and Social Change in the Wake of India's Recent Sodomy Cases Deepa Das Acevedo University of Alabama - School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.ua.edu/fac_articles Recommended Citation Deepa Das Acevedo, Sovereignty and Social Change in the Wake of India's Recent Sodomy Cases, 40 B. C. Int'l & Comp. L. Rev. 1 (2017). Available at: https://scholarship.law.ua.edu/fac_articles/450 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Alabama Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of Alabama Law Scholarly Commons. SOVEREIGNTY AND SOCIAL CHANGE IN THE WAKE OF INDIA'S RECENT SODOMY CASES DEEPA DAS ACEVEDO* Abstract: American constitutional law scholars have long questioned whether courts can truly drive social reform, and this uncertainty remains even in the wake of recent landmark decisions affecting the LGBT community. In contrast, court watchers in India-spurred by developments in a special type of legal ac- tion developed in the late 1970s known as public interest litigation (PIL)-have only recently begun to question the judiciary's ability to promote progressive social change. Indian scholarship on this point has veered between despair that PIL cases no longer reliably produce good outcomes for India's most disadvan- taged and optimism that public interest litigation can be returned to its glory days of heroic judicial intervention. Perhaps no pair of cases so nicely captures this dichotomy as the 2009 decision in Naz Foundation v. -

Jodhaa Akbar

JODHAA AKBAR ein Film von Ashutosh Gowariker Indien 2008 ▪ 213 Min. ▪ 35mm ▪ Farbe ▪ OmU KINO START: 22. Mai 2008 www.jodhaaakbar.com polyfilm Verleih Margaretenstrasse 78 1050 Wien Tel.:+43-1-581 39 00-20 www:polyfilm.at [email protected] Pressebetreuung: Allesandra Thiele Tel.:+43-1-581 39 00-14 oder0676-3983813 Credits ...................................................2 Kurzinhalt...............................................3 Pressenotiz ............................................3 Historischer Hintergrund ........................3 Regisseur Ashutosh Gowariker..............4 Komponist A.R. Rahman .......................5 Darsteller ...............................................6 Pressestimmen ......................................9 .......................................................................................Credits JODHAA AKBAR Originaltitel: JODHAA AKBAR Indien 2008 · 213 Minuten · OmU · 35mm · FSK ab 12 beantragt Offizielle Homepage: www.jodhaaakbar.com Regie ................................................Ashutosh Gowariker Drehbuch..........................................Ashutosh Gowariker, Haidar Ali Produzenten .....................................Ronnie Screwvala and Ashutosh Gowariker Musik ................................................A. R. Rahman Lyrics ................................................Javed Akhtar Kamera.............................................Kiiran Deohans Ausführende Produzentin.................Sunita Gowariker Koproduzenten .................................Zarina Mehta, Deven Khote -

UTV Acquires the Feature Film Rights of Ashwin Sanghi's

UTV acquires the Feature Film rights of Ashwin Sanghi’s ‘Chanakya’s Chant’ ~ A film based on the #1 National Bestseller to go on floors soon ~ Mumbai, Wednesday, June 15th, 2011: UTV Motion Pictures has acquired rights to Ashwin Sanghi’s national bestseller - Chanakya’s Chant, published by Westland. The interesting fast-paced story based on politics in two radically different eras will now be adapted into a film by the studio. Chanakya's Chant, a historical political thriller, released by Westland in January 2011, shot into the Top-5 Bestsellers of India within 2 weeks of its launch, proving that Chanakya’s neetis are as relevant today as they were in ancient times. The book narrates two parallel political tales, one in Chanakya’s puranic Bharat 2300 years ago and the other in post-independence contemporary India. While the ancient story is largely historical, based upon Chanakya’s rise to power and the clever tactics applied by him towards installing Chandragupta Maurya on the throne, the modern story is mostly fictional and tells the tale of Kanpur’s Pandit Gangasagar Mishra who draws inspiration from the master strategist Chanakya and employs his strategies in a modern context to get his protégée Chandini Gupta appointed to the highest office in India. On announcing the film, Siddharth Roy Kapur, CEO, UTV Motion Pictures, said "Chanakya’s Chant is one of those rare books with a storyline that has the potential to be translated into a superbly cinematic and immensely entertaining screenplay. The tale is about the underbelly of national politics which the book superbly exposes, where strategies developed by Chanakya 2300 years ago are still as valid in the modern day political scenario. -

Bollywood As National(Ist) Cinema Violence, Patriotism and the National- Popular in Rang De Basanti

Third Text, Vol. 23, Issue 6, November, 2009, 703–716 Bollywood as National(ist) Cinema Violence, Patriotism and the National- Popular in Rang De Basanti Neelam Srivastava This essay sets out to explore the relationship between violence, patrio- tism and the national-popular within the medium of film by examining the Indian film-maker Rakeysh Mehra’s recent Bollywood hit, Rang de Basanti (Paint It Saffron, 2006). The film can be seen to form part of a body of work that constructs and represents violence as integral to the emergence of a national identity, or rather, its recuperation. Rang de Basanti is significant in contemporary Indian film production for the enormous resonance it had among South Asian middle-class youth, both in India and in the diaspora. It rewrites, or rather restages, Indian nationalist history not in the customary pacifist Gandhian vein, but in the mode of martyrdom and armed struggle. It represents a more ‘masculine’ version of the nationalist narrative for its contemporary audiences, by retelling the story of the Punjabi revolutionary Bhagat Singh as an Indian hero and as an example for today’s generation. This essay argues that its recuperation of a violent anti-colonial history is, in fact, integral to the middle-class ethos of the film, presenting the viewers with a bourgeois nationalism of immediate and timely appeal, coupled with an accessible (and politically acceptable) social activism. As the 1. Quoted in Namrata Joshi, sociologist Ranjini Majumdar noted, ‘the film successfully fuels the ‘My Yellow Icon’, Outlook middle-class fantasy of corruption being the only problem of the coun- India, online edition, 20 1 February 2006, available try’. -

Fascist Imaginaries and Clandestine Critiques: Young Hindi Film Viewers Respond to Violence, Xenophobia and Love in Cross- Border Romances

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by LSE Research Online Shakuntala Banaji Fascist imaginaries and clandestine critiques: young Hindi film viewers respond to violence, xenophobia and love in cross- border romances Book section Original citation: Banaji, Shakuntala (2007) Fascist imaginaries and clandestine critiques: young Hindi film viewers respond to violence, xenophobia and love in cross-border romances. In: Bharat, Meenakshi and Kumar, Nirmal, (eds.) Filming the line of control: the Indo–Pak relationship through the cinematic lens. Routledge, Oxford, UK. ISBN 9780415460941 © 2007 Routledge This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/27360/ Available in LSE Research Online: May 2011 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s submitted version of the book section. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Fascist imaginaries and clandestine critiques: young Hindi film viewers respond to violence, xenophobia and love in cross-border romances Shakuntala Banaji1 Tarang: I’ve watched Hindi films all my life. -

Dil Se / from the Heart (1998, Mani Ratnam, India)

A Level Film Studies - Focus Film Factsheet Dil Se / From the Heart (1998, Mani Ratnam, India) Component 2: Global Filmmaking • Sumptuous colour cinematography by Perspectives (AL) Santosh Sivan covers the different regions of the Indian sub-continent evoking the Core Study Areas contrasting geographic and ethnic features. Key Elements of Film Form • After the interval the story moves to New Meaning & Response Delhi with consequent tighter framing. The Contexts of Film • In Dil Se the songs (apart from E Ajnabi) are fantasies bookended by realities. The Rationale for study cinematography signals the change between these two modes. During the dance sequences Dil Se demonstrates the key characteristics frequent use of camera zoom, moving of a mainstream Bollywood film: a two-part camera, change of camera angles echo the structure, big stars, spectacular song and dance rhythmic pattern of the song. At the ending sequences, themes of Indian identity and the of the film the cinematography is much more struggle between love and duty. However, it tied to the conventions of realism. goes against the usual Bollywood narrative in its mixing of a romantic obsessive love story with a Mise-en-Scène serious and thought provoking political thriller. • Lavish mise-en-scène in terms of the costumes as well as the scenery. During the song and dance sequences both change constantly STARTING POINTS - Useful which is one of the features of the Bollywood Sequences and timings/links film. In Satrangi Re Meghna starts off in black, then white, orange, yellow, green, red, Satrangi Re – a song and dance sequence inspired blue, white, purple then white again. -

Spectacle Spaces: Production of Caste in Recent Tamil Films

South Asian Popular Culture ISSN: 1474-6689 (Print) 1474-6697 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsap20 Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films Dickens Leonard To cite this article: Dickens Leonard (2015) Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films, South Asian Popular Culture, 13:2, 155-173, DOI: 10.1080/14746689.2015.1088499 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14746689.2015.1088499 Published online: 23 Oct 2015. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rsap20 Download by: [University of Hyderabad] Date: 25 October 2015, At: 01:16 South Asian Popular Culture, 2015 Vol. 13, No. 2, 155–173, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14746689.2015.1088499 Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films Dickens Leonard* Centre for Comparative Literature, University of Hyderabad, Hyderabad, India This paper analyses contemporary, popular Tamil films set in Madurai with respect to space and caste. These films actualize region as a cinematic imaginary through its authenticity markers – caste/ist practices explicitly, which earlier films constructed as a ‘trope’. The paper uses the concept of Heterotopias to analyse the recurrence of spectacle spaces in the construction of Madurai, and the production of caste in contemporary films. In this pursuit, it interrogates the implications of such spatial discourses. Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films To foreground the study of caste in Tamil films and to link it with the rise of ‘caste- gestapo’ networks that execute honour killings and murders as a reaction to ‘inter-caste love dramas’ in Tamil Nadu,1 let me narrate a political incident that occurred in Tamil Nadu – that of the formation of a socio-political movement against Dalit assertion in December 2012. -

A Pedagogical Tool for the Application of Critical Discourse Analysis in the Interpretation of Film and Other Multimodal Discursive Practices

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2015 Active Critical Engagement (ACE): A Pedagogical Tool for the Application of Critical Discourse Analysis in the Interpretation of Film and Other Multimodal Discursive Practices Sultana Aaliuah Shabazz University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Social and Philosophical Foundations of Education Commons Recommended Citation Shabazz, Sultana Aaliuah, "Active Critical Engagement (ACE): A Pedagogical Tool for the Application of Critical Discourse Analysis in the Interpretation of Film and Other Multimodal Discursive Practices. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2015. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/3607 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Sultana Aaliuah Shabazz entitled "Active Critical Engagement (ACE): A Pedagogical Tool for the Application of Critical Discourse Analysis in the Interpretation of Film and Other Multimodal Discursive Practices." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Education. Barbara J. Thayer-Bacon, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Harry Dahms, Rebecca Klenk, Lois Presser Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. -

List of Organisations/Individuals Who Sent Representations to the Commission

1. A.J.K.K.S. Polytechnic, Thoomanaick-empalayam, Erode LIST OF ORGANISATIONS/INDIVIDUALS WHO SENT REPRESENTATIONS TO THE COMMISSION A. ORGANISATIONS (Alphabetical Order) L 2. Aazadi Bachao Andolan, Rajkot 3. Abhiyan – Rural Development Society, Samastipur, Bihar 4. Adarsh Chetna Samiti, Patna 5. Adhivakta Parishad, Prayag, Uttar Pradesh 6. Adhivakta Sangh, Aligarh, U.P. 7. Adhunik Manav Jan Chetna Path Darshak, New Delhi 8. Adibasi Mahasabha, Midnapore 9. Adi-Dravidar Peravai, Tamil Nadu 10. Adirampattinam Rural Development Association, Thanjavur 11. Adivasi Gowari Samaj Sangatak Committee Maharashtra, Nagpur 12. Ajay Memorial Charitable Trust, Bhopal 13. Akanksha Jankalyan Parishad, Navi Mumbai 14. Akhand Bharat Sabha (Hind), Lucknow 15. Akhil Bharat Hindu Mahasabha, New Delhi 16. Akhil Bharatiya Adivasi Vikas Parishad, New Delhi 17. Akhil Bharatiya Baba Saheb Dr. Ambedkar Samaj Sudhar Samiti, Basti, Uttar Pradesh 18. Akhil Bharatiya Baba Saheb Dr. Ambedkar Samaj Sudhar Samiti, Mirzapur 19. Akhil Bharatiya Bhil Samaj, Ratlam District, Madhya Pradesh 20. Akhil Bharatiya Bhrastachar Unmulan Avam Samaj Sewak Sangh, Unna, Himachal Pradesh 21. Akhil Bharatiya Dhan Utpadak Kisan Mazdoor Nagrik Bachao Samiti, Godia, Maharashtra 22. Akhil Bharatiya Gwal Sewa Sansthan, Allahabad. 23. Akhil Bharatiya Kayasth Mahasabha, Amroh, U.P. 24. Akhil Bharatiya Ladhi Lohana Sindhi Panchayat, Mandsaur, Madhya Pradesh 25. Akhil Bharatiya Meena Sangh, Jaipur 26. Akhil Bharatiya Pracharya Mahasabha, Baghpat,U.P. 27. Akhil Bharatiya Prajapati (Kumbhkar) Sangh, New Delhi 28. Akhil Bharatiya Rashtrawadi Hindu Manch, Patna 29. Akhil Bharatiya Rashtriya Brahmin Mahasangh, Unnao 30. Akhil Bharatiya Rashtriya Congress Alap Sankyak Prakosht, Lakheri, Rajasthan 31. Akhil Bharatiya Safai Mazdoor Congress, Jhunjhunu, Rajasthan 32. Akhil Bharatiya Safai Mazdoor Congress, Mumbai 33. -

Healing of Discernible Brackish from Municipal Drinking Water by Charcoal Filtration Method at Jijgiga, Ethiopia Udhaya Kumar

ISSN XXXX XXXX © 2019 IJESC Research Article Volume 9 Issue No.4 Healing of Discernible Brackish from Municipal Drinking Water by Charcoal Filtration Method at Jijgiga, Ethiopia Udhaya Kumar. K Lecturer Department of Water Resource and Irrigation Engineering University of Jijgiga, Ethiopia Abstract: Jijiga is a city in eastern region of Ethiopia country and the Jijiga is capital of Somali Region (Ethiopia). Located in the Jijiga Zone approximately 80 km (50 miles) east of Harar and 60 km (37 miles) west of the border with Somalia, this city has an elevation of 1,609 meters above the sea level. The population of this city was 185000 in the year 2015. The elevation of this city is 1609m from sea level. The natural water source for jijiga is limited, most of the time people getting limited quantity of water. The main source of this city is a small pond and one spring. The rainy season also not that much. The municipality supplying water to every house based upon intermittent system, the time limit is morning only (8am to 9am). The municipality water contains discernible brackish. The public using this water for drinking and cooking purpose, it wills danger for human health. My focus is planning to remove discernible brackish by distinct method. My research results indicate the removal of discernible brackish from drinking water by simple charcoal filtration method for low cost. Keywords: Discernible brackish, Human health, Filtration, Low cost, Main source, Municipality, Intermittent system, Distinct method. I. INTRODUCTION charcoal. Only the water is reached to the second layer. Then the filtered water is collected separately to another container The climate condition of Jijgiga city is not constant and also without discernible brackish. -

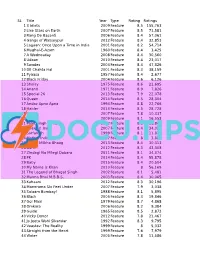

Aspirational Movie List

SL Title Year Type Rating Ratings 1 3 Idiots 2009 Feature 8.5 155,763 2 Like Stars on Earth 2007 Feature 8.5 71,581 3 Rang De Basanti 2006 Feature 8.4 57,061 4 Gangs of Wasseypur 2012 Feature 8.4 32,853 5 Lagaan: Once Upon a Time in India 2001 Feature 8.2 54,714 6 Mughal-E-Azam 1960 Feature 8.4 3,425 7 A Wednesday 2008 Feature 8.4 30,560 8 Udaan 2010 Feature 8.4 23,017 9 Swades 2004 Feature 8.4 47,326 10 Dil Chahta Hai 2001 Feature 8.3 38,159 11 Pyaasa 1957 Feature 8.4 2,677 12 Black Friday 2004 Feature 8.6 6,126 13 Sholay 1975 Feature 8.6 21,695 14 Anand 1971 Feature 8.9 7,826 15 Special 26 2013 Feature 7.9 22,078 16 Queen 2014 Feature 8.5 28,304 17 Andaz Apna Apna 1994 Feature 8.8 22,766 18 Haider 2014 Feature 8.5 28,728 19 Guru 2007 Feature 7.8 10,337 20 Dev D 2009 Feature 8.1 16,553 21 Paan Singh Tomar 2012 Feature 8.3 16,849 22 Chakde! India 2007 Feature 8.4 34,024 23 Sarfarosh 1999 Feature 8.1 11,870 24 Mother India 1957 Feature 8 3,882 25 Bhaag Milkha Bhaag 2013 Feature 8.4 30,313 26 Barfi! 2012 Feature 8.3 43,308 27 Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara 2011 Feature 8.1 34,374 28 PK 2014 Feature 8.4 55,878 29 Baby 2015 Feature 8.4 20,504 30 My Name Is Khan 2010 Feature 8 56,169 31 The Legend of Bhagat Singh 2002 Feature 8.1 5,481 32 Munna Bhai M.B.B.S.