Fireflyer Companion & Letter Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEW THIS WEEK from MARVEL COMICS... Amazing Spider-Man

NEW THIS WEEK FROM MARVEL COMICS... Amazing Spider-Man #16 Fantastic Four #7 Daredevil #2 Avengers No Road Home #3 (of 10) Superior Spider-Man #3 Age of X-Man X-Tremists #1 (of 5) Captain America #8 Captain Marvel Braver & Mightier #1 Savage Sword of Conan #2 True Believers Captain Marvel Betrayed #1 ($1) Invaders #2 True Believers Captain Marvel Avenger #1 ($1) Black Panther #9 X-Force #3 Marvel Comics Presents #2 True Believers Captain Marvel New Ms Marvel #1 ($1) West Coast Avengers #8 Spider-Man Miles Morales Ankle Socks 5-Pack Star Wars Doctor Aphra #29 Black Panther vs. Deadpool #5 (of 5) Marvel Previews Captain Marvel 2019 Sampler (FREE) Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur #40 Mr. and Mrs. X Vol. 1 GN Spider-Geddon Covert Ops GN Iron Fist Deadly Hands of Kung Fu Complete Collection GN Marvel Knights Punisher by Peyer & Gutierrez GN NEW THIS WEEK FROM DC... Heroes in Crisis #6 (of 9) Flash #65 "The Price" part 4 (of 4) Detective Comics #999 Action Comics #1008 Batgirl #32 Shazam #3 Wonder Woman #65 Martian Manhunter #3 (of 12) Freedom Fighters #3 (of 12) Batman Beyond #29 Terrifics #13 Justice League Odyssey #6 Old Lady Harley #5 (of 5) Books of Magic #5 Hex Wives #5 Sideways #13 Silencer #14 Shazam Origins GN Green Lantern by Geoff Johns Book 1 GN Superman HC Vol. 1 "The Unity Saga" DC Essentials Nightwing Action Figure NEW THIS WEEK FROM IMAGE... Man-Eaters #6 Die Die Die #8 Outcast #39 Wicked & Divine #42 Oliver #2 Hardcore #3 Ice Cream Man #10 Spawn #294 Cold Spots GN Man-Eaters Vol. -

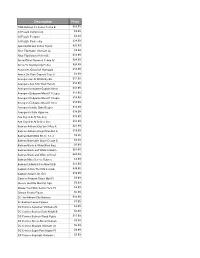

Toys and Action Figures in Stock

Description Price 1966 Batman Tv Series To the B $29.99 3d Puzzle Dump truck $9.99 3d Puzzle Penguin $4.49 3d Puzzle Pirate ship $24.99 Ajani Goldmane Action Figure $26.99 Alice Ttlg Hatter Vinimate (C: $4.99 Alice Ttlg Select Af Asst (C: $14.99 Arrow Oliver Queen & Totem Af $24.99 Arrow Tv Starling City Police $24.99 Assassins Creed S1 Hornigold $18.99 Attack On Titan Capsule Toys S $3.99 Avengers 6in Af W/Infinity Sto $12.99 Avengers Aou 12in Titan Hero C $14.99 Avengers Endgame Captain Ameri $34.99 Avengers Endgame Mea-011 Capta $14.99 Avengers Endgame Mea-011 Capta $14.99 Avengers Endgame Mea-011 Iron $14.99 Avengers Infinite Grim Reaper $14.99 Avengers Infinite Hyperion $14.99 Axe Cop 4-In Af Axe Cop $15.99 Axe Cop 4-In Af Dr Doo Doo $12.99 Batman Arkham City Ser 3 Ras A $21.99 Batman Arkham Knight Man Bat A $19.99 Batman Batmobile Kit (C: 1-1-3 $9.95 Batman Batmobile Super Dough D $8.99 Batman Black & White Blind Bag $5.99 Batman Black and White Af Batm $24.99 Batman Black and White Af Hush $24.99 Batman Mixed Loose Figures $3.99 Batman Unlimited 6-In New 52 B $23.99 Captain Action Thor Dlx Costum $39.95 Captain Action's Dr. Evil $19.99 Cartoon Network Titans Mini Fi $5.99 Classic Godzilla Mini Fig 24pc $5.99 Create Your Own Comic Hero Px $4.99 Creepy Freaks Figure $0.99 DC 4in Arkham City Batman $14.99 Dc Batman Loose Figures $7.99 DC Comics Aquaman Vinimate (C: $6.99 DC Comics Batman Dark Knight B $6.99 DC Comics Batman Wood Figure $11.99 DC Comics Green Arrow Vinimate $9.99 DC Comics Shazam Vinimate (C: $6.99 DC Comics Super -

How Disney Visual Media Influences Children's Perceptions of Family a Content Analysis an Honors Thesis

Family on Film: How Disney Visual Media Influences Children's Perceptions of Family A Content Analysis An Honors Thesis (SOC 424) by Alexandra Garman Thesis Advisor Dr. Richard Petts ) c' __ / Ball State University Muncie, Indiana December, 2011 Expected Date of Graduation December 17, 2011 ," I . / ' 1 Abstract The Walt Disney Company has held a decades-long grip on family entertainment through visual media, amusement parks, clothing, toys, and even food. American children, and children throughout the world, are readily exposed to Disney's visual media as often as several times a day through film and television shows. As such, reviewing what this media says and analyzing its potential affects on our society can be beneficial in determining what messages children are receiving regarding values and norms concerning family. Specifically, analyzing family structure can help to provide an outlook for future normative structure. Depicted family interactions may also reflect how realistic families interact, what children expect from their families, and how children may interact with their own families in coming years. This study seeks to analyze various media released in recent years (2006-2011) and how these media portray family structure and interaction. Family appears to be variant in structure, including varied parental figures, as well as occasionally including non-biological figures. However, the family structure still seems, on the whole, to fit or otherwise promote (through inability of variants to do well) the traditional family model ofheterosexual, married biological parents and their offspring. Interestingly, Disney appears to place a great emphasis on fathers. Interactions between family members are relatively balanced, with some families being more positive in interaction and others being more negative. -

2K Unveils Stellar Video Game Line

2K Unveils Stellar Video Game Line-up for 2006 Electronic Entertainment Expo; Line-up Includes Highly- Anticipated Titles such as The Da Vinci Code(TM), Prey, Sid Meier's Civilization IV: Warlords and NBA 2K7 May 10, 2006 8:31 AM ET NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)--May 10, 2006--2K and 2K Sports, publishing labels of Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc. (NASDAQ: TTWO), today announced a strong line-up for Electronic Entertainment Expo 2006 (E3) taking place at the Los Angeles Convention Center from May 10-12, 2006. From 2K, the line-up includes titles based on blockbuster entertainment brands such as The Da Vinci Code(TM) and Family Guy and popular comic book franchises The Darkness and Ghost Rider, as well as original next generation games such as Prey and BioShock. 2K is also featuring highly-anticipated titles from Firaxis Games, including Sid Meier's Civilization IV: Warlords and Sid Meier's Railroads! as well as the Firaxis and Firefly Studios collaboration title CivCity: Rome. Other eagerly awaited titles include Stronghold Legends(TM) along with Dungeon Siege II(R): Broken World(TM) and Dungeon Siege: Throne of Agony(TM), based on the acclaimed Dungeon Siege(R) franchise. In addition, the 2K Sports line-up features the next installments from top-rated franchises such as NHL 2K7, NBA 2K7 and College Hoops 2K7. 2K Line-up Includes: BioShock BioShock is an innovative role-playing shooter from Irrational Games who was named IGN's 2005 Developer of the Year. BioShock immerses players into a war-torn underwater utopia, where mankind has abandoned their humanity in their quest for perfection. -

A Collection of Texts Celebrating Joss Whedon and His Works Krista Silva University of Puget Sound, [email protected]

Student Research and Creative Works Book Collecting Contest Essays University of Puget Sound Year 2015 The Wonderful World of Whedon: A Collection of Texts Celebrating Joss Whedon and His Works Krista Silva University of Puget Sound, [email protected] This paper is posted at Sound Ideas. http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/book collecting essays/6 Krista Silva The Wonderful World of Whedon: A Collection of Texts Celebrating Joss Whedon and His Works I am an inhabitant of the Whedonverse. When I say this, I don’t just mean that I am a fan of Joss Whedon. I am sincere. I live and breathe his works, the ever-expanding universe— sometimes funny, sometimes scary, and often heartbreaking—that he has created. A multi- talented writer, director and creator, Joss is responsible for television series such as Buffy the Vampire Slayer , Firefly , Angel , and Dollhouse . In 2012 he collaborated with Drew Goddard, writer for Buffy and Angel , to bring us the satirical horror film The Cabin in the Woods . Most recently he has been integrated into the Marvel cinematic universe as the director of The Avengers franchise, as well as earning a creative credit for Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. My love for Joss Whedon began in 1998. I was only eleven years old, and through an incredible moment of happenstance, and a bit of boredom, I turned the television channel to the WB and encountered my first episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer . I was instantly smitten with Buffy Summers. She defied the rules and regulations of my conservative southern upbringing. -

On Liberty It’S Our Best Best Of

On Liberty It’s Our Best Best of... Issue Ever A guide to the city’s top Sights Entertainment Restaurants Bars Important Health Warning About Playing Video Games Table of Contents Photosensitive Seizures A very small percentage of people may experience a seizure when exposed to certain 02 Installation visual images, including flashing lights or patterns that may appear in video games. 04 Game Controls Even people who have no history of seizures or epilepsy may have an undiagnosed condition that can cause these “photosensitive epileptic seizures” while watching 08 Letter from the Editor video games. 10 Places Best Sights These seizures may have a variety of symptoms, including lightheadedness, altered vision, eye or face twitching, jerking or shaking of arms or legs, disorientation, 12 Entertainment Best Place to Chill confusion, or momentary loss of awareness. Seizures may also cause loss of consciousness or convulsions that can lead to injury from falling down or striking 14 Restaurants Best Burger nearby objects. 16 Bars Best Brew Immediately stop playing and consult a doctor if you experience any of these 18 Feature Dating in the City symptoms. Parents should watch for or ask their children about the above symptoms—children and teenagers are more likely than adults to experience these 20 Technology Top Gadgets seizures. The risk of photosensitive epileptic seizures may be reduced by taking the following precautions: Sit farther from the screen; use a smaller screen; play in a well- 22 Credits lit room; and do not play when you are drowsy or fatigued. 32 Warranty If you or any of your relatives have a history of seizures or epilepsy, consult a doctor before playing. -

The Beetle Fauna of Dominica, Lesser Antilles (Insecta: Coleoptera): Diversity and Distribution

INSECTA MUNDI, Vol. 20, No. 3-4, September-December, 2006 165 The beetle fauna of Dominica, Lesser Antilles (Insecta: Coleoptera): Diversity and distribution Stewart B. Peck Department of Biology, Carleton University, 1125 Colonel By Drive, Ottawa, Ontario K1S 5B6, Canada stewart_peck@carleton. ca Abstract. The beetle fauna of the island of Dominica is summarized. It is presently known to contain 269 genera, and 361 species (in 42 families), of which 347 are named at a species level. Of these, 62 species are endemic to the island. The other naturally occurring species number 262, and another 23 species are of such wide distribution that they have probably been accidentally introduced and distributed, at least in part, by human activities. Undoubtedly, the actual numbers of species on Dominica are many times higher than now reported. This highlights the poor level of knowledge of the beetles of Dominica and the Lesser Antilles in general. Of the species known to occur elsewhere, the largest numbers are shared with neighboring Guadeloupe (201), and then with South America (126), Puerto Rico (113), Cuba (107), and Mexico-Central America (108). The Antillean island chain probably represents the main avenue of natural overwater dispersal via intermediate stepping-stone islands. The distributional patterns of the species shared with Dominica and elsewhere in the Caribbean suggest stages in a dynamic taxon cycle of species origin, range expansion, distribution contraction, and re-speciation. Introduction windward (eastern) side (with an average of 250 mm of rain annually). Rainfall is heavy and varies season- The islands of the West Indies are increasingly ally, with the dry season from mid-January to mid- recognized as a hotspot for species biodiversity June and the rainy season from mid-June to mid- (Myers et al. -

Batman #87 Superman #19 Batman Curse of the Whit

NEW THIS WEEK FROM DC... Wonder Woman #750 (with "Decades" Variants) Batman #87 Superman #19 Batman Curse of the White Knight #6 (of 6) Batman Superman #6 Year of the Villain Hell Arisen #2 (of 4) Detective Comics #1019 Basketful of Heads #4 (of 7) Far Sector #3 (of 12) Birds of Prey Giant #1 Batman Beyond #40 Batgirl #43 Metal Men #4 (of 12) John Constantine Hellblazer #3 Shazam #10 Red Hood Outlaw #42 Wonder Twins #11 (of 12) Books of Magic #16 Dollar Comics Batman Huntress Cry for Blood #1 Birds of Prey Harley Quinn GN NEW THIS WEEK FROM MARVEL... Amazing Spider-Man #38 Fantastic Four #18 Excalibur #6 Guardians of the Galaxy #1 Marauders #6 Atlantis Attacks #1 (of 5) Captain Marvel #14 Conan Serpent War #4 (of 4) Black Panther #20 Web of Venom Good Son #1 Ruins of Ravencroft Dracula #1 True Believers Criminally Insane Dracula True Believers Criminally Insane Purple Man Valkyrie Jane Foster Vol. 1 GN X-Statix Complete Collection Vol. 1 GN Fantastic Four Mystery Minis FF Mister Fantastic Funko Pop FF Human Torch Funko Pop FF Silver Surfer Funko Pop FF Super Skrull Funko Pop ALSO NEW THIS WEEK... Once & Future #6 (of 6) Folklords #3 (of 5) Kidz #1 Vampire State Building #4 Gung Ho #2 Visitor #2 (of 6) Kill Lock #2 (of 6) Wellington #2 (of 5) Heartbeat #3 (of 5) Red Sonja Age of Chaos #1 Edgar Allan Poe's Snifter of Terror 2 #4 Ether Disappearance of Violet Bell #5 (of 5) Mirka Andolfo's Unsacred #3 Roku #4 (of 4) Vampirella #7 Vampironica New Blood #2 Black Terror #4 Catalyst Prime Seven Days #4 (of 7) Count Crowley Reluctant Monster Hunter #4 (of 4) Heist How to Steal a Planet #3 I Can Sell You a Body #2 (of 4) Triage #5 (of 5) Wasted Space #13 Lumberjanes #70 Meeting Comics GN Gudetama Love for the Lazy HC NEW THIS WEEK FROM IMAGE.. -

Molecular Systematics of the Firefly Genus Luciola

animals Article Molecular Systematics of the Firefly Genus Luciola (Coleoptera: Lampyridae: Luciolinae) with the Description of a New Species from Singapore Wan F. A. Jusoh 1,* , Lesley Ballantyne 2, Su Hooi Chan 3, Tuan Wah Wong 4, Darren Yeo 5, B. Nada 6 and Kin Onn Chan 1,* 1 Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum, National University of Singapore, Singapore 117377, Singapore 2 School of Agricultural and Wine Sciences, Charles Sturt University, Wagga Wagga 2678, Australia; [email protected] 3 Central Nature Reserve, National Parks Board, Singapore 573858, Singapore; [email protected] 4 National Parks Board HQ (Raffles Building), Singapore Botanic Gardens, Singapore 259569, Singapore; [email protected] 5 Department of Biological Sciences, National University of Singapore, Singapore 117543, Singapore; [email protected] 6 Forest Biodiversity Division, Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong 52109, Malaysia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (W.F.A.J.); [email protected] (K.O.C.) Simple Summary: Fireflies have a scattered distribution in Singapore but are not as uncommon as many would generally assume. A nationwide survey of fireflies in 2009 across Singapore documented 11 species, including “Luciola sp. 2”, which is particularly noteworthy because the specimens were collected from a freshwater swamp forest in the central catchment area of Singapore and did not fit Citation: Jusoh, W.F.A.; Ballantyne, the descriptions of any known Luciola species. Ten years later, we revisited the same locality to collect L.; Chan, S.H.; Wong, T.W.; Yeo, D.; new specimens and genetic material of Luciola sp. 2. Subsequently, the mitochondrial genome of that Nada, B.; Chan, K.O. -

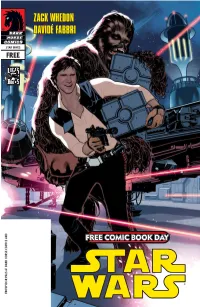

Zack Whedon Davidé Fabbri Zack Whedon 2/17/12 1:11 Pm ® S R

ZACKZACK WHEDONWHEDON ® DAVIDÉDAVIDÉ FABBRIFABBRI STAR WARS FREE ® FROM YOUR PALS AT DARK HORSE COMICS AND COMICS HORSE DARK AT PALS YOUR FROM FCBD12 SW-SEREN.indd 1 2/17/12 1:11 PM FCBD12 SW-SEREN.indd 2 tions, or locales, without satiric intent, is coincidental. Printed by Cadmus Communications, Easton, PA, U.S.A. tions, orlocales,without satiricintent,iscoincidental.Printed byCadmusCommunications,Easton, PA, Anyresemblancetoactual persons(livingordead),events,institu either aretheproduct oftheauthor’simaginationorareused fictitiously. writtenpermissionofDarkHorse Comics,Inc.Names,characters,places,andincidentsfeaturedinthispublication without theexpress categories andcountries.Allrightsreserved. Noportionofthispublicationmaybereproducedortransmitted,inanyform or are ©2012LucasfilmLtd.DarkHorse Comics® andtheDarkHorselogoaretrademarksofComics,Inc.,registered inva Wars andillustrationsforStar Text ©2012LucasfilmLtd.&™.Allrightsreserved.Usedunderauthorization. Milwaukie, OR97222.StarWars ArtoftheBadDeal,”May2012.PublishedbyDarkHorseComics, Inc.,10956SEMainStreet, WARS—“The STAR FREE COMICBOOK DAY: RONDA D MICHAEL A D ZACK WHEDON ZACK advertising sales: (503) 905-2370 » comic shop locator service: (888)266-4226 service: (503)905-2370»comicshop locator sales: advertising ALLA ALLA DA AVIDÉ FABBRI AVIDÉ MIKE RANDY RANDY M H M C assistant editor assistant collection editor P F HRISTIAN REDD cover art SIERRA R lettering V T ATTISON T ICHARDSON INA ALESSI ECCHIA talk about this issue online at: online at: aboutthisissue talk Pencils HO UGHES Colors STRADLE publisher D script designer YE YE AVID M editor Inks HAHN LINS AS Y STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS ANDERMAN at lucas licensing. ANDERMAN at ALDERS, CAROL special thankstoJ ROEDER Comics! Horse Dark from pals this your at free offering enjoy please afirst-timer, or time reader along you’re whether But Emperor. -

The AUSS Firefly: a Distributed Sensing and Coordination Platform for First-Year Engineering Education

The AUSS FIREfly: A Distributed Sensing and Coordination Platform for First-Year Engineering Education Derrick Yeo1 , Derek A. Paley2 Department of Aerospace Engineering, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland , 20742, U.S.A This paper describes an embedded computing and sensing system developed to serve the needs of the Autonomous Unmanned Systems Stream (AUSS), a two-semester sequence at the University of Maryland that provides first-year students with an inquiry-based introduction to concepts in engineering and autonomy. AUSS is part of the UMD First-year Innovation and Research Experience program (FIRE), a campus-wide initiative that provides course-based undergraduate research experiences for first-year students. FIRE aims to propel students towards planning, conducting and reporting research that is relevant to the scientific community. To serve its educational mission, the AUSS needs to equip incoming freshmen with the necessary technical capabilities to pursue engineering research in autonomous systems. The AUSS FIREfly is a robotics kit designed to be a training tool and a research platform. Each device is assembled and programmed by an individual student, exposing the builder to topics such as circuit design, information theory, and computer science. Once completed, the FIREfly uses onboard infrared transceivers to emulate the photic system of a firefly, supporting group-led experiments in multi-agent synchronization. The devices are also designed to serve as nodes in a distributed sensor network when equipped with additional measurement modules such as airspeed probes. This paper presents the design features of the AUSS FIREfly system within the context of the challenges faced by a first-year research education experience. -

Radio Essentials 2012

Artist Song Series Issue Track 44 When Your Heart Stops BeatingHitz Radio Issue 81 14 112 Dance With Me Hitz Radio Issue 19 12 112 Peaches & Cream Hitz Radio Issue 13 11 311 Don't Tread On Me Hitz Radio Issue 64 8 311 Love Song Hitz Radio Issue 48 5 - Happy Birthday To You Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 21 - Wedding Processional Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 22 - Wedding Recessional Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 23 10 Years Beautiful Hitz Radio Issue 99 6 10 Years Burnout Modern Rock RadioJul-18 10 10 Years Wasteland Hitz Radio Issue 68 4 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night Radio Essential IssueSeries 44 Disc 44 4 1975, The Chocolate Modern Rock RadioDec-13 12 1975, The Girls Mainstream RadioNov-14 8 1975, The Give Yourself A Try Modern Rock RadioSep-18 20 1975, The Love It If We Made It Modern Rock RadioJan-19 16 1975, The Love Me Modern Rock RadioJan-16 10 1975, The Sex Modern Rock RadioMar-14 18 1975, The Somebody Else Modern Rock RadioOct-16 21 1975, The The City Modern Rock RadioFeb-14 12 1975, The The Sound Modern Rock RadioJun-16 10 2 Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love Radio Essential IssueSeries 22 Disc 22 4 2 Pistols She Got It Hitz Radio Issue 96 16 2 Unlimited Get Ready For This Radio Essential IssueSeries 23 Disc 23 3 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone Radio Essential IssueSeries 22 Disc 22 16 21 Savage Feat. J. Cole a lot Mainstream RadioMay-19 11 3 Deep Can't Get Over You Hitz Radio Issue 16 6 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun Hitz Radio Issue 46 6 3 Doors Down Be Like That Hitz Radio Issue 16 2 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes Hitz Radio Issue 62 16 3 Doors Down Duck And Run Hitz Radio Issue 12 15 3 Doors Down Here Without You Hitz Radio Issue 41 14 3 Doors Down In The Dark Modern Rock RadioMar-16 10 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time Hitz Radio Issue 95 3 3 Doors Down Kryptonite Hitz Radio Issue 3 9 3 Doors Down Let Me Go Hitz Radio Issue 57 15 3 Doors Down One Light Modern Rock RadioJan-13 6 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone Hitz Radio Issue 31 2 3 Doors Down Feat.