Pop Gym Zine #2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sport-Discipline-Specialita

SPORT DISCIPLINA SPECIALITA' Automobilismo Fuoristrada 4X4 Cinofilia Attività Sportiva Cinotecnica Ability Sport Acquatici Attività Ginnico-Motorie Acquatiche Applicative alle Discipline del Nuoto Acqua e Disabilità Sport Acquatici Attività Ginnico-Motorie Acquatiche Applicative alle Discipline del Nuoto Acqua Fitness Sport Acquatici Attività Ginnico-Motorie Acquatiche Applicative alle Discipline del Nuoto Acqua Gym Sport Acquatici Attività Ginnico-Motorie Acquatiche Applicative alle Discipline del Nuoto Acquaerobic Sport Acquatici Attività Ginnico-Motorie Acquatiche Applicative alle Discipline del Nuoto Acquafitness Sport Acquatici Attività Ginnico-Motorie Acquatiche Applicative alle Discipline del Nuoto Acquapilates Sport Acquatici Attività Ginnico-Motorie Acquatiche Applicative alle Discipline del Nuoto Acquapsicomotricità - Gravidanza Sport Acquatici Attività Ginnico-Motorie Acquatiche Applicative alle Discipline del Nuoto Acquapsicomotricità neonatale Acquapsicomotricità per Soggetti Sport Acquatici Attività Ginnico-Motorie Acquatiche Applicative alle Discipline del Nuoto Autistici Acquapsicomotricità per Soggetti Sport Acquatici Attività Ginnico-Motorie Acquatiche Applicative alle Discipline del Nuoto Autistici e Disabili Sport Acquatici Attività Ginnico-Motorie Acquatiche Applicative alle Discipline del Nuoto Acquapsicomotricità per Soggetti Disabili Sport Acquatici Attività Ginnico-Motorie Acquatiche Applicative alle Discipline del Nuoto Acquapsicomotricità prenatale Sport Acquatici Attività Ginnico-Motorie Acquatiche Applicative -

The Effectiveness of Kickboxing Techniques and Its Relation to Fights Won by Knockout

ORIGINAL ARTICLE The effectiveness of kickboxing techniques and its relation to fights won by knockout Authors’ Contribution: Tadeusz Ambroży1ABCD, Łukasz Rydzik1ABCD, Andrzej Kędra1BCD, A Study Design 1BD 2DE 2DE 2BCD B Data Collection Dorota Ambroży , Marta Niewczas , Ewa Sobiło , Wojciech Czarny C Statistical Analysis D Manuscript Preparation 1 Faculty of Physical Education and Sport, Institute of Sport, University of Physical Education in Krakow, Krakow, Poland E Funds Collection 2 College of Medical Sciences, Institute of Physical Culture Studies, University of Rzeszow, Rzeszow, Poland Received: 29 December 2019; Accepted: 21 January 2020; Published online: 17 February 2020 AoBID: 13154 Abstract Background and Study Aim: Ratio of fights won is important to kickboxers on professional and amateur levels. Knockout is the most eco- nomical way of winning the fight. The objective of the paper is the effectiveness of kickboxing techniques and their impact on winning the fight by knockout. Material and Methods: There were 156 participants in the study (61 amateurs and 95 professionals). Their total number of fights won by knockout was 188 and the amateur competitions they participated in complied with the K-1 ruleset. Fighters were 19 to 32 years old and their training experience was on the average 7.36 yrs. ±3.24 yrs. The shortest training lasted 3 yrs. and the longest one 18 yrs. The study was conducted using the analysis of vid- eos of professional fights as well as diagnostic survey conducted in a group of amateur fighters. The survey in- cluded questions about training experience and techniques used in a fight won by knockout. -

Analysis and Evaluation of Sports Fight in Mixed Martial Arts with Using of Augmented Reality As an Element of Coach Control in This Discipline

ANALYSIS AND EVALUATION OF SPORTS FIGHT IN MIXED MARTIAL ARTS WITH USING OF AUGMENTED REALITY AS AN ELEMENT OF COACH CONTROL IN THIS DISCIPLINE dr hab. Kazimierz Witkowski*, prof. nadzw., dr Paweł Adam Piepiora*, mgr Igor Stariczenkow* Introduction Nowadays tournaments ‘without rules’ are more and more organized. Fights that are known as the Portuguese ‘vale tudo’, also called ‘mixed martial arts’ or ‘no holds barred’ have become nowadays extremely popular. It should be noted that the ‘fight without rules’ have strict rules. Not only, it is defined the place and time of fight, but they also banned brutal techniques which do not affect the course of battle, i.e. biting and techniques which obviously can lead to disability. These rules apply in primary battles ‘vale tudo’ while numerous tournaments bring a variety of constraints, thus they are often called ‘mixed martial arts’. The original idea of MMA tournaments was to confront techniques of different styles, to check the efficiency of individual techniques in sports fight with a minimum of restrictions. Nowadays it still happens, because the fighters prepare using a whole experience of different styles of fighting. Every fight is a clash of motion skills and intellect behind the technique and tactics1,2. The greater complexity characterized by the fight, the more tactical and intellectual challenge is. The aim of the study is to verify competitive sports in the MMA heavyweight fights. The research questions are: which technical elements will dominate in the MMA fight in the stand-up? -

Outside the Cage: the Political Campaign to Destroy Mixed Martial Arts

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2013 Outside The Cage: The Political Campaign To Destroy Mixed Martial Arts Andrew Doeg University of Central Florida Part of the History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Doeg, Andrew, "Outside The Cage: The Political Campaign To Destroy Mixed Martial Arts" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 2530. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/2530 OUTSIDE THE CAGE: THE CAMPAIGN TO DESTROY MIXED MARTIAL ARTS By ANDREW DOEG B.A. University of Central Florida, 2010 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2013 © 2013 Andrew Doeg ii ABSTRACT This is an early history of Mixed Martial Arts in America. It focuses primarily on the political campaign to ban the sport in the 1990s and the repercussions that campaign had on MMA itself. Furthermore, it examines the censorship of music and video games in the 1990s. The central argument of this work is that the political campaign to ban Mixed Martial Arts was part of a larger political movement to censor violent entertainment. -

Mixed Martial Arts

COMPILED BY : - GAUTAM SINGH STUDY MATERIAL – SPORTS 0 7830294949 Mixed Martial Arts - Overview Mixed Martial Arts is an action-packed sport filled with striking and grappling techniques from a variety of combat sports and martial arts. During the early 1900s, many different mixed-style competitions were held throughout Europe, Japan and the Pacific Rim. CV Productions Inc. showed the first regulated MMA league in the US in 1980 called the Tough Guy Contest, which was later renamed as Battle of the Superfighters. In 1983, the Pennsylvania State Senate passed a bill which prohibited the sport. However, in 1993, it was brought back into the US TVs by the Gracie family who found the Ultimate Fighting Championships (UFC) which most of us have probably heard about on our TVs. These shows were promoted as a competition which intended in finding the most effective martial arts in an unarmed combat situation. The competitors fought each other with only a few rules controlling the fight. Later on, additional rules were established ensuring a little more safety for the competitors, although it still is quite life-threatening. A Brief History of Mixed Martial Arts THANKS FOR READING – VISIT OUR WEBSITE www.educatererindia.com COMPILED BY : - GAUTAM SINGH STUDY MATERIAL – SPORTS 0 7830294949 The history of MMA dates back to the Greek era. There was an ancient Olympic combat sport called as Pankration which had features of combination of grappling and striking skills. Later, this sport was passed on to the Romans. An early example of MMA is Greco-Roman Wrestling (GRW) in the late 1880s, where players fought without few to almost zero safety rules. -

Response to Paul Bowman's Article ‘Instituting Reality in Martial Arts Practice' Abstract

JOMEC Journal Journalism, Media and Cultural Studies Dialogue: Conquest of Reality: Response to Paul Bowman’s ‘Instituting Reality in Martial Arts Practice’ Kyle Barrowman The University of Chicago Email: [email protected] A discussion in response to Paul Bowman's article ‘Instituting Reality in Martial Arts Practice' Abstract In this Dialogue, Kyle Barrowman responds to Paul Bowman’s article ‘Instituting Reality in Martial Arts Practice' and poses questions pertinent to future development of martial arts studies. Contributor Note Kyle Barrowman is a postgraduate student at The University of Chicago. He has previously published essays in Offscreen, The International Journal of Žižek Studies, and Senses of Cinema, on subjects ranging from Michael Mann and Alfred Hitchcock to Bruce Lee and Steven Seagal. cf.ac.uk/Jomec/Jomecjournal/5-june2014/Barrowman_Response.pdf Introduction not least so that he would be able to facilitate the conversation and elaborate, As excited and honored as I was to be clarify, and/or counter some of my able to contribute an essay to this Martial comments in ways that will hopefully Arts Studies issue of the JOMEC Journal, enrich the work currently being done in the greatest thrill for me regarding the this exciting new endeavor. whole experience was being able to establish a line of communication with Paul Bowman. From when I initially 1. The Problem of Institutionalization submitted my essay for this issue in December of 2012 to when the issue was Given the title of Paul Bowman’s essay, it published this past June, my e-mail seems only natural to begin by broaching correspondence with Dr. -

Ufc Tonight Quotes

FOX Sports 1 UFC TONIGHT Show Quotes – 5/27/15 CONDIT ON BEATING ALVES: “I NEED TO PUSH THE PACE, GRIND HIM AND GET HIM TIRED.” Cormier On How Alves Beats Condit: “His leg kicks are the key. He has to throw leg kicks.” UFC FIGHT NIGHT Preview, Plus Condit and Rutten Interviews on UFC TONIGHT LOS ANGELES, CA – UFC TONIGHT hosts Daniel Cormier and Kenny Florian are joined by guest host Michael Bisping and preview UFC FIGHT NIGHT: CONDIT VS. ALVES. Florian and Cormier interview Carlos Condit, while Cormier and Bisping interview Bas Rutten. Karyn Bryant and Ariel Helwani add reports. UFC TONIGHT Host Daniel Cormier on being the new champ: “It’s the most amazing thing I’ve ever experienced, outside of my kids. It’s something you dream about, but you never know if you’re going to accomplish it.” Cormier on his game plan against Anthony Johnson: “The game plan was to try to implement wrestling, make him go hard and make him go long. You can wear out guys with a lot muscle. The grind can wear out the arms. But he hit me hard. That wasn’t a right hand that hit me, that was a missile shot out of a rocket launcher. He’s a stud. He’s confident and hits hard.” Cormier on Johnson putting the belt around him: “I just want to say thank you Anthony Johnson. You see many guys win and then the belt is put around the waist by Dana White. Johnson did that and made my time special. -

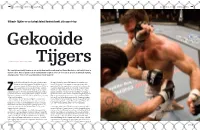

Ultimate Fighter En Ex-Student Antoni Hardonk Knokt Zich Naar De Top Gekooide

ULTIMATE FIGHT CHALLENGE ULTIMATE FIGHT CHALLENGE Ultimate Fighter en ex-student Antoni Hardonk knokt zich naar de top Gekooide TEKST JENS OLDE KALTER FOTOGRAFIE UFC / JENS OLDEKALTER Tijgers Met een diploma bedrijfskunde op zak en zijn beschaafde voorkomen had Antoni Hardonk zo het bedrijfsleven in kunnen rollen. Maar in plaats van de bestuurskamer stapt hij liever de kooi van de UFC in, de Ultimate Fighting Championship. “Ik ben niet bang voor pijn, wel voor opgeven.’ ijn hoofd wordt bijna door het gaas gedrukt en met Als zijn Nederlandse Sinner-bril hem niet zou verraden, zou vuisten en ellebogen bewerkt. Het publiek in de Sa- Antoni Hardonk in LA zo kunnen doorgaan voor een lokale cramento Arena joelt. Vij!ienduizend man. Of het nu quarterback. Een hip zwart shirt om een sterk lijf, met benen als wel of geen pijn doet weet hij niet precies. Comfor- brugpijlers onder snelle surfshorts. We lopen op Santa Monica tabel is het in elk geval niet. Liggend op zijn rug, en Boulevard in zijn nieuwe stad en Hardonk verwoordt ontspan- Z schijnbaar kansloos, bewaart Antoni Hardonk zijn rust. Hij is nen zijn gedachten over zijn eerste gevecht. Zijn overwinning op professioneel vechter en weet waar hij mee bezig is. Sherman knock-out hee! laten zien waarvoor hij naar Amerika is gekomen. Pendergarst, de reus van 115 kilo die nu op hem ligt, gaat vroeg Niet om punten te boksen, maar om zich naar de Heavyweight- of laat een fout maken. titel van de UFC te knokken, momenteel de Champions League Die fout komt. De scheidsrechter grijpt in en het gevecht van de Mixed Martial Arts (MMA): niet alleen qua niveau maar wordt onderbroken. -

Featuring Advice from UFC Hall of Famers Randy Couture, Ken Shamrock, Bas Rutten, Pat Miletich, Dan Severn and More! Online

narm4 (Ebook pdf) The Ultimate Guide to Preventing and Treating MMA Injuries: Featuring advice from UFC Hall of Famers Randy Couture, Ken Shamrock, Bas Rutten, Pat Miletich, Dan Severn and more! Online [narm4.ebook] The Ultimate Guide to Preventing and Treating MMA Injuries: Featuring advice from UFC Hall of Famers Randy Couture, Ken Shamrock, Bas Rutten, Pat Miletich, Dan Severn and more! Pdf Free Dr. Jonathan Gelber M.D. M.S. ePub | *DOC | audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #1405868 in Books Gelber M D M S Jonathan 2016-05-10Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 8.90 x .40 x 6.00l, .0 #File Name: 1770411720200 pagesThe Ultimate Guide to Preventing and Treating MMA Injuries Featuring advice from UFC Hall of Famers Randy Couture Ken Shamrock Bas Rutten Pat Miletich Dan Severn and more | File size: 76.Mb Dr. Jonathan Gelber M.D. M.S. : The Ultimate Guide to Preventing and Treating MMA Injuries: Featuring advice from UFC Hall of Famers Randy Couture, Ken Shamrock, Bas Rutten, Pat Miletich, Dan Severn and more! before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Ultimate Guide to Preventing and Treating MMA Injuries: Featuring advice from UFC Hall of Famers Randy Couture, Ken Shamrock, Bas Rutten, Pat Miletich, Dan Severn and more!: 2 of 2 people found the following review helpful. This is truly a great read if you are interested in Preventing and Treating ...By MikeSiljanoskiI purchased this book about 3 weeks ago and plan on sharing it with several friends that train for MMA. -

California State Athletic Commision

STATE OF CALIFORNIA-STATE AND CONSUMER SERVICES AGENCY ARNOLD SCHWARZENEGGER. Governor blATi:;· OF CALiF California State Athletic Commission 2005 Evergreen St., Ste. #2010 Sacramento, CA 95815 www.dca.ca.gov/csac/ (916) 263-2195 FAX (916) 263-2197 Members of the Commission Commissioner John Frierson, Chair Action may be taken on any item listed on Commissioner Christopher Giza, Vice-Chair the agenda except public comment. Commissioner Van Lemons, M.D. Commissioner Steve Alexander Commissioner DeWayne Zinkin Commissioner Eugene Hernandez MEETING AGENDA Monday, July 26,2010 9:00 A.M. to Close of Business Location Department of Health Care Services Building 1500 Capitol Avenue Sacramento, CA 1. Call to order/Roll call/Pledge of allegiance 2. Approval of Minutes a. February 22, 2010 b. Apri120,2010 c. May 17,2010 4. Executive Officer Report a. Status of Office b. Personnel Update c. Status of Information Technology Projects d. Budget Update e. Physician Training 5. Public Comment on Items Not on the Agenda - Note: The Commission may not discuss or take action on any matter raised during this public comment section, except to decide whether to place the matter on the agenda ofa future meeting. [Government Code Sections 11125, 11125.7(a)} 6. Muay Thai Presentation on Possible Delegation of Authority for Amateur Muay Thai Pursuant to Business and Professions Code section 18646 - Brian Dobler 7. DCA Director's Report 8. Presentation of Recommended Changes to MMA Scoring System - Possible Regulatory Change - Nelson Hamilton, John McCarthy, Herb Dean 9. Yearly Review For CAMO Delegation a. CAMO rules changes - update on Health and Safety of Fighters b. -

Team Lakay: Pressed to Stay on Top Of

MDM THURSDAY | MARCH 7, 2019 P11 Sometime in 2011, the and Evolve MMA owner brandishes in his recent Lakay’s achievements can be venerable Davao journalist Chatri Sityodtong, as the matches. described as phenomenal. Ram Maxey texted me to ask number one mixed martial Younger at 31 and a It also seemed to thrive how come Eduard Folayang arts camp in Asia. former Wushu champion in adversity, battling in the speaks good English. “A fan just asked me himself, Belingon is words of Sangiao, “fatigue, It seemed that Ram was who I think is the best fight considered the most criticism, pressure and even following up a mixed martial team in Asia. I have massive explosive of Team Lakay’s the elements (when we had arts promotion in Singapore respect for all fight teams, fighters. This is not to practice for week after the where Folayang and a Davao but I believe there is no surprising for someone who power lines were knocked MMA fighter were matched question that Team Lakay is idolizes Bruce Lee and who down by a typhoon).” against foreign fighters. now the #1 fight team in Asia is also well-versed in the Sangiao said the Folayang, then an MMA today,” Sityodtong wrote on Ifugao version of wrestling challenge for 2019 is for the fighter into his second year, a social media post. Team Lakay: Pressed known as bultong. There team to stay razor sharp and turned out victorious in his He added: “Despite a was a never dull fight to focus in training to keep match and was handed the very modest budget and to stay on top of MMA when Belingon steps into up with the rest of the fold. -

Kevin Randleman Named to 2020 Ufc Hall of Fame Class

For Immediate Release May 16, 2020 KEVIN RANDLEMAN NAMED TO 2020 UFC® HALL OF FAME CLASS Las Vegas – UFC® today announced that former UFC heavyweight champion Kevin Randleman has been named to the UFC Hall of Fame class for 2020 as a Pioneer. The 2020 UFC Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony, presented by Toyo Tires®, will take place later this year and will be streamed live on UFC FIGHT PASS®. “Kevin Randleman was one of the first real athletes in the early days of UFC,” UFC President Dana White said. “He was a two-time NCAA Division I National Champion and All-American wrestler at The Ohio State University. He was the fifth heavyweight champion in UFC history and one of the first athletes to successfully compete at both heavyweight and light heavyweight. He was a pioneer of the sport and it’s an honor to induct him into the UFC Hall of Fame Class of 2020.” Randleman will enter the UFC Hall of Fame as the 17th member of the Pioneer Era wing. The Pioneers Era category includes athletes who turned professional before November 17, 2000 (when the unified rules of mixed martial arts were adopted), are a minimum age of 35, or have been retired for one year or more. A veteran of 33 professional fights during his 15-year career, Randleman compiled a record of 17-16 (4-3, UFC), including wins over UFC Hall of Famer Maurice Smith, UFC®23: ULTIMATE JAPAN 2 middleweight tournament champion Kenichi Yamamoto and 2006 PRIDE FC world open-weight grand prix champion Mirko Cro Cop.