The 'Kagame Reforms' of the AU: Will They Stick?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TDB Joins Eminent Discussants on Sustainable Development Goals in Kigali

TDB joins eminent discussants on Sustainable Development Goals in Kigali Opened in July 2016, The Sustainable Development Goals Center for Africa (SDGC/A) was created in 2016 and launched in Kigali on 27 January 2017. The SDGC/A is an international organization that supports governments, civil society, businesses and academic institutions in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in Africa. A conference was organized to launch the new institution and was attended by development partners, government leaders and private sector representatives. The President and CEO of TDB, Mr Admassu Tadesse joined other eminent participants and panellists including His Excellency Rwandese President Paul Kagame and His Excellency Minister Claver Gatete, Minister of Finance of Rwanda and TDB Governor. Mr Aliko Dangote, Africa’s richest man and one of the strongest advocates of the SDGs also joined the panellists to bring his private sector perspective. According to SGDC/A the investment gap for Africa to achieve the SDGs is between an incremental outlay of $200 billion and $1.2 trillion per annum. TDB’s President joined panellists to discuss how Africa can achieve The SDGs By 2030. Mr Tadesse emphasized the key role of DFIs in supporting the continent in achieving SDGs and the crucial role that regional DFIs play in fostering regional integration. In the case of TDB, Member States are using the Bank as a platform to grow regional trade as well as a vehicle to host innovative initiatives such as regional infrastructure funds. Several regional DFIs exchanged on their strategies to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Many of TDB’s partners and development banks of the region were in attendance, notably the Agriculture Finance Cooperation, Development Bank of Zambia, Infrastructure Development Bank of Zimbabwe and the Uganda Development Bank. -

East African Development Bank

East African Development Bank Directors’ Report and Financial Statements For the year ended 31 December 2017 East African Development Bank Directors’ Report and Financial Statements For the year ended 31 December 2017 Table of contents Page Annual report: Governing Council, Advisory Panel, Directors, Officers and Administration 1 – 2 Directors’ report 3 Statement of directors’ responsibilities 4 Report of the independent auditor 5 – 8 Financial statements: Statement of comprehensive income 9 Statement of financial position 10 Statement of changes in equity 11 Statement of cash flows 12 Notes 13 – 66 East African Development Bank Governing Council, Advisory Panel, Directors, Officers and Administration Governing Council • Hon. Dr. Philip Mpango (Chairman) Minister for Finance, United Republic of Tanzania • Mr. Henry K. Rotich Cabinet Secretary, The National Treasury, Republic of Kenya • Hon. Amb. Claver Gatete Minister for Finance and Economic Planning, Republic of Rwanda • Hon. Matia Kasaija Minister for Finance, Planning and Economic Development, Republic of Uganda Directors • Dr Kamau Thugge (Chairman) Principal Secretary, the National Treasury, Republic of Kenya • Mr Keith Muhakanizi Permanent Secretary and Secretary to the Treasury, Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development, Republic of Uganda • Mr Caleb Rwamuganza Permanent Secretary, Secretary to the Treasury, Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning, Republic of Rwanda • Mr James Doto Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Finance, United Republic of Tanzania • Mr Francis N. Karuiru Private Sector Representative, Republic of Kenya • Mrs Khadija I. Simba Private Sector Representative, Republic of Tanzania • Mr Mbundu Faustin Private Sector Representative, Republic of Rwanda • Mr. James Tumusiime Private Sector Representative, Republic of Uganda • Mr Trevor De Kock African Development Bank Representative • Ms Vivienne Yeda Director General, East African Development Bank Advisory Panel • Mr Mahesh K. -

SPEAKER PROFILES Official Opening of Rwanda Sustainable Energy

SPEAKER PROFILES Official Opening of Rwanda Sustainable Energy Week 2018 Amb. Claver Gatete, Minister of Infrastructure Rwanda Ministry of Infrastructure Biography Amb. Claver Gatete has been the Minister of Infrastructure since April 2018. Prior to this appointment, he served as Minister of Finance and Economic Planning starting in February 2013. He had previously served as the Governor of the National Bank of Rwanda (2011 to 2013). Amb. Gatete also served as Rwanda’s Ambassador to the Website: United Kingdom, Ireland, and Iceland from November 2005 to December 2009. He is www.mininfra.gov.rw also currently a member of the Presidential Advisory Council. In addition, Amb. Gatete’s previous posts include Personal Representative of the President on NEPAD Steering Committee, and National Economist at the Rwanda United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Amb. Gatete has held various positions on Key Boards of Directors including: Chairman of Rwanda Revenue Authority, Chairman of School of Finance and Banking; member of the Board of the National Bank of Rwanda; Chairman of National Privatization Technical Committee; and Vice-Chairman of Community Development Fund. Amb. Gatete holds a Masters in Agricultural Economics from the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, B.C., Canada (1993) and an undergraduate degree from the same University (1991). About the Rwanda Ministry of Infrastructure The MININFRA is a department of the Government of Rwanda. It is responsible for infrastructure policy and development throughout the country. The Ministry's mission is to ensure the sustainable development of infrastructure and to contribute to economic growth with a view to enhancing the quality of life of the population. -

Newsletter Issue No: 5 REG January - March, 2020

Newsletter Issue No: 5 REG January - March, 2020 REG CELEBRATED THE MILLIONTH CUSTOMER GOVERNMENT OF RWANDA - AfDB APPROVES €8 MILLION NYABARONGO II HYDRO WORLD BANK SIGN US$ 100 TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE GRANT TO POWER PROJECT GETS MILLION FINANCING AGREEMENT SUPPORT RUZIZI IV HYDRO POWER US$ 214 MILLION TO SUPPORT RWANDA’S COVID19 PROJECT IN THE GREAT LAKES FINANCING BOOST RESPONSE IN ENERGY. REGION Toll @reg_rwanda Rwanda Energy Group Ltd Reg Rwanda regltd www.reg.rw Free 2727 Issue No: 5 January - March, 2020 REG CELEBRATED THE MILLIONTH CUSTOMER ............................. AFDB APPROVES €8 MILLION TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE GRANT TO SUPPORT RUZIZI IV HYDRO POWER PROJECT ............................. IN THE GREAT LAKES REGION HOW ACCESS TO ELECTRICITY FACILITATED YOUNG ............................. ENTREPRENEUR‘S AMBITIONS ENERGY MINISTERS PUSH THE COMPLETION OF ............................. RUSUMO POWER PLANT BEFORE 2021 RWANDA, DR CONGO SIGN VALIDATION ACT FOR THE ............................. SAFE EXPLOITATION OF LAKE KIVU GAS RESOURCES NYABARONGO II HYDRO POWER PROJECT GETS US$ ............................. 214 MILLION FINANCING BOOST A POSITIVE CHANGE IN THE LIVES OF AROUND 22,000 ............................. FAMILIES WHO GOT ELECTRICITY 2 YEARS AGO 11 PEOPLE CAUGHT ACCUSED OF ELECTRICITY THEFT ............................. IN THE FIRST QUARTER OF 2020 INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S DAY 2020 CELEBRATED ON ............................. HIGH GEAR BY REG STAFF REG BEAT UTB IN THE FINAL TO WIN KAYUMBA ............................. MEMORIAL Newsletter -

Reflections on a Three -Year J

SDGs IMPLEMENTATION IN AFRICA REFLECTIONS ON A THREE-YEAR JOURNEY 14th June 2019 | Kigali Convention Center, Rwanda CONFERENCE BROCHURE Reflections on a Three -Year Journey SDGs IMPLEMENTATION IN AFRICA – REFLECTIONS ON A THREE-YEAR JOURNEY 14th June 2019 | Kigali Convention Center, Kigali, Rwanda BACKGROUND Following the adoption of the SDGs in September 2015, Africa has made many commitments towards achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Agenda 2030 and the Africa Union Agenda 2063. At the adoption of the SDGs, Africa’s starting point was lower than all the other regions. Africa was at cross roads, with low tax revenue to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) on the one end of the problem, and enormous development needs on the other end. Infrastructure gaps alone were estimated at USD 130–170 billion a year, with a financing gap in the range USD 68–108 billion. The SDGs were conceptualized and adopted during a period of global economic and financial transition. Emerging evidence over the last three years (2015 – 2018) of tracking SDGs progress on an annual basis indicates complex challenges still prevail in Africa. Many intricacies, ambiguities and questions continue to predominate and stand in the pathway forward towards Africa’s achievement of these Goals. It is without doubt that there is much “unfinished business” that must be addressed for the SDGs to be achieved in Africa, foremost of which are the need (i) to bridge understanding between SDG conceptualization and implementation pathways, (ii) to address global financing for the SDGs in Low Income Countries, particularly those in Africa, (iii) to raise domestic financing efforts, which still are suboptimal with an estimated gap of 3-5% of GDP, and (iv) to engage the private sector. -

ESID Working Paper No. 120 the Rise of the Economic Technocracy In

ESID Working Paper No. 120 The rise of the economic technocracy in Rwanda: A case of a bureaucratic pocket of effectiveness or state-building prioritisation? Benjamin Chemouni 1 July, 2019 1 University of Cambridge Email correspondence: [email protected] ISBN: 978-1-912593-26-2 email: [email protected] Effective States and Inclusive Development Research Centre (ESID) Global Development Institute, School of Environment, Education and Development, The University of Manchester, Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9PL, UK www.effective-states.org The rise of the economic technocracy in Rwanda: A case of bureaucratic pocket of effectiveness or state-building prioritisation? Abstract The Rwandan Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning (MINECOFIN) is recognised as the most effective organisation in the Rwandan state. The objective of the paper is to understand the organisational and political factors influencing MINECOFIN’s performance since the genocide and link them to the wider conversation on the role of pockets of effectiveness (PoEs) in state-building in Africa. It argues that, because of the Rwandan political settlement and elite vulnerability, MINECOFIN is not a PoE but only a good performer in a generally well functioning state. The Ministry overperforms first because, unsurprisingly, the nature of its tasks is specific, requires little embeddedness and allows a great exposure to donors, making its mandate easier to deliver in comparison to other organisations. MINECOFIN also performs better than other state organisations because it is, more than others, at the frontline of the elite legitimation project since it is the organisation through which resources are channelled, priorities decided, and developmental efforts coordinated. -

List of Participants FIP SUB-COMMITTEE COUNTRY MEMBERS

Meeting of the FIP Sub-Committee Washington D.C. Wednesday, December 13-Thursday, December 14, 2017 List of Participants FIP SUB-COMMITTEE COUNTRY MEMBERS FIP Sub-Committee Country FIP Sub-Committee Member Email [email protected]/ Bangladesh Shamshur Rahman Khan/ [email protected] Brazil Erivaldo Alfredo Gomes Congo, Democratic Republic of John Muloba Kitonge [email protected] Denmark / Niels Hedegaard / [email protected] / Spain Beatriz Curiel [email protected] Gambia, The/ Muhammad Jaiteh/ [email protected] / Zambia Chitembo K Chunga [email protected] Indonesia / Agus Justiano/ [email protected] / Tajikistan Suhrob Olimov [email protected] Japan Munenari Nomura [email protected] Mexico Berenice Hernandez Toro [email protected] Norway Mari Martinsen [email protected] Sweden Marita Olson [email protected] United Kingdom Ben Green [email protected] United States Katie Berg [email protected] COUNTRY PARTICIPANTS BANGLADESH Md Abdullah Abraham Hossain Assistant Conservator of Forests Government of Bangladesh Dhaka, Bangladesh Email: [email protected] Roksana Khan Deputy Secretary Ministry of Finance Economic Relations Division(ERD) Sher-E-Bangla Nagar, Agrgaon Dhaka, Bangladesh Email: [email protected] Shamshur Rahman Khan Deputy Secretary Ministry of Environment and Forests Bangladesh Secretariat Dhaka, Bangladesh Email: [email protected] BRAZIL Ludmila Vidigal Silva General Coordinator for International Institutions Policy Ministry of Finance, Department of International Affairs Esplanada dos Ministerios, Block P, 20 Andar Brasilia / DF, Brazil Email Address: [email protected] CAMEROON Marcus Abbo Ministry of Forests and Wildlife – MINFOF P.O Box 320 Yaounde, Cameroon Charles Assamba Ministry of Forests and Wildlife – MINFOF P.O Box 320 Yaounde, Cameroon Oumarou Chimmoun Ministry of Forests and Wildlife – MINFOF P.O Box 320 Yaounde, Cameroon Climate Investment Funds – FIP Sub-Committee Meeting – Washington D.C. -

Rwanda Partners with Mas...He Government of Rwanda

ENGLISH | KINYARWANDA | CHECK MAIL | CONTACT US Search... Republic of Rwanda Repubulika y'u Rwanda LEARN ABOUT RWANDA GOVERNMENT ABOUT THE GOVERNMENT SERVICES PRESS ROOM GOV CONNECT Home Rwanda partners with Massachusetts Institute of Technology to accelerate economic growth and development Rwanda partners with Massachusetts Institute of Technology to accelerate economic growth and development Rwanda partners with Massachusetts Institute of Technology to TWITTER FEED accelerate economic growth and development This cute infant is to be named during #KwitaIzina2013. Her mother is English Kinyarwanda called Isaro. How would you name her Share Tweet and why? pic.twitter.com/iV8BNxHrOb 12 baby gorillas are to be named during #KwitaIzina2013. Join us as we celebrate nature and empower communities. SERVICES FOR CITIZENS Travel Documents Social Security National ID Driving License Health System FOR VISITORS Visit Rwanda Work in Rwanda Kigali- 21 May 2013 Invest in Rwanda The Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning today hosted a Decision Science Symposium with members of the Abdul Business in Rwanda Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL) from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Study in Rwanda The symposium focused on how to maximize the effectiveness of policies and programs in Rwanda by drawing on lessons from hundreds of randomized trials already conducted in many developing countries, including Rwanda. The symposium, dubbed “from evidence to policy”, attracted a host of Rwandan policy makers from the Ministries of Finance and Economic Planning, Education, Agriculture, Infrastructure and Health. Speaking at the symposium, the Minister of Cabinet affairs Protais Musoni said Rwanda was now at a stage of economic development where evidence is critical for policy formulation to accelerate the gains made in poverty reduction and growth. -

Industry Partnership Meeting for Infrastructure & Urban Development

Industry Agenda Industry Partnership Meeting for Infrastructure & Urban Development Industries African Strategic Infrastructure Initiative Abuja, Nigeria 7-9 May 2014 May 2014 High-level Meeting on the African Strategic Infrastructure Initiative Contents 4 High-level Meeting on the African © World Economic Forum Strategic Infrastructure Initiative 2014 - All rights reserved. 6 Private Session “Financing Africa’s The viewpoints expressed herein attempt to reflect the collective opinion of various individuals who have contributed to the research Infrastructure” and development of this report. They do not necessarily imply an agreed position among them or institutional endorsement by any participating company or organization involved in the work or mentioned in the report, or of the World Economic Forum. 9 List of Participants REF 300514 11 Contact Information 2 Industry Partnership Meeting for Infrastructure & Urban Development Industries 01 02 03 04 05 01: Arun Kumar, Senior Financial Associate, Philipp Roesler, Managing Director and Member Frontline Development Partners, United Arab of the Managing Board, World Economic Forum; Emirates; and Zhong Jianhua, Special Representative Mohan Vivekanandan, Group Executive, on African Affairs of the Chinese Government, Strategy, Development Bank of Southern Africa, People’s Republic of China South Africa; Carlos Lopes, Undersecretary-General and 02: Macky Sall, President of Senegal Executive Secretary, United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA), Addis Ababa; 03: Klaus Schwab, Founder -

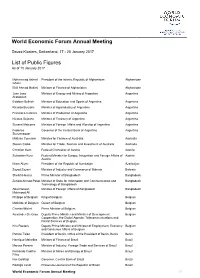

List of Public Figures

World Economic Forum Annual Meeting Davos-Klosters, Switzerland, 17 - 20 January 2017 List of Public Figures As of 10 January 2017 Mohammad Ashraf President of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Afghanistan Ghani Eklil Ahmad Hakimi Minister of Finance of Afghanistan Afghanistan Juan Jose Minister of Energy and Mining of Argentina Argentina Aranguren Esteban Bullrich Minister of Education and Sports of Argentina Argentina Ricardo Buryaile Minister of Agroindustry of Argentina Argentina Francisco Cabrera Minister of Production of Argentina Argentina Nicolas Dujovne Minister of Treasury of Argentina Argentina Susana Malcorra Minister of Foreign Affairs and Worship of Argentina Argentina Federico Governor of the Central Bank of Argentina Argentina Sturzenegger Mathias Cormann Minister for Finance of Australia Australia Steven Ciobo Minister for Trade, Tourism and Investment of Australia Australia Christian Kern Federal Chancellor of Austria Austria Sebastian Kurz Federal Minister for Europe, Integration and Foreign Affairs of Austria Austria Ilham Aliyev President of the Republic of Azerbaijan Azerbaijan Zayed Zayani Minister of Industry and Commerce of Bahrain Bahrain Sheikh Hasina Prime Minister of Bangladesh Bangladesh Zunaid Ahmed Palak Minister of State for Information and Communication and Bangladesh Technology of Bangladesh Abul Hassan Minister of Foreign Affairs of Bangladesh Bangladesh Mahmood Ali Philippe of Belgium King of Belgium Belgium Mathilde of Belgium Queen of Belgium Belgium Charles Michel Prime Minister of Belgium Belgium -

Africa Group I Constituency the World Bank Group

AFRICA GROUP I CONSTITUENCY THE WORLD BANK GROUP AFRICA GROUP I CONSTITUENCY S P E C I A L VOLUME 4, ISSUE 1 SPECIAL EDITION, FE BRUARY 2017 P O I N T S O F INSIDEINTEREST: THIS VOLUMEMessage 4, ISSUE from 1 the Executive DirectorSPECIAL EDITION, Message fromBriefly thehighlight yourExecutive point of 1 FEBRUARY 2017 Director interest here. Message from the Executive Director Briefly highlight your point of interest here. Africa Group 1 elects New 2 In this regard, my Office has developed its Executive DirectorBriefly highlight your and point of own strategic work program dubbed ‘Agenda interest here. Appoints Alternate 24’ as the hallmark of my tenure for the Executive DirectorBriefly highlight your point of interest here. period November 2016 – October 2018, and which has been shared with the Governors of Change of Leadership- 3 It is a privilege and honor to pre- perity in a sustainable manner. accountability, which we have Africa Group 1 sent my message in this first edi- our Constituency.embraced Agenda as the 24hallmarks includes of our Constituency tion of our Newsletter since tak- The WBG “Forwardactivities Look” exer-aimed administrationat addressing thefor expressedthe period In Memory of 4 ing office as Executive Director cise, which was endorsedconcerns by of the our Novemberauthorities, 2016 as –articulated October 2018. in Mr. Dismas Baransaka for our Constituency. I wish to Board of Governorsour at recent the 2016 DC Member Statements, within express my sincere appreciation IMF/WBG Annualthe frameworkMeetings, ofBesides -

Office Holders Coffee Year 2006/07

ED 2004/06 International Coffee Organization 4 December 2006 Organización Internacional del Café Organização Internacional do Café Original: English Organisation Internationale du Café E Office holders Coffee year 2006/07 1. The Executive Director presents his compliments and, for the information of Members, attaches a document containing details of office holders and Members of the Executive Board with their usual representatives for coffee year 2006/07. The composition of the Private Sector Consultative Board (PSCB), Quality Committee, Finance Committee, Statistics Committee and Virtual Screening Committee is also included together with office holders for the Promotion Committee and the Working Group on the Future of the Agreement. 2. Members are requested to keep the Executive Director informed of any subsequent changes as they occur. An updated version of this list will be posted on the Office Holders section of the ICO website (www.ico.org). INTERNATIONAL COFFEE ORGANIZATION COFFEE YEAR 2006/07 OFFICE HOLDERS INTERNATIONAL COFFEE COUNCIL1* Chairman EC – Italy Mr. Mauro Orefice Ministry for Productive Activities 1st Vice-Chairman Japan Mr. Hiroshi Aimoto First Secretary (Agriculture) Embassy of Japan 2nd Vice-Chairman India Mr. G.V. Krishna Rau Chairman Coffee Board of India 3rd Vice-Chairman Indonesia Mr. Dewa Sastrawan Minister Counsellor (Economic Affairs) Embassy of the Republic of Indonesia MEMBERS OF THE EXECUTIVE BOARD Chairman Guatemala Excelentísimo Señor Embajador José Angel López Camposeco Presidente Asociación Nacional del Café (ANACAFE) Vice-Chairman Honduras Señor Iván Romero Encargado de Negocios Representante permanente ante la OIC EXPORTING MEMBERS Angola Representing: Angola, Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, Gabon, Ghana and Togo Representative: Excelentíssimo Senhor Gilberto Buta Lutucuta Ministro da Agricultura e do desenvolvimento Rural Alternates: Sr.