Download (714Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Towncouncil Community Magazine

Inside - all your local events, clubs & groups FolkestoQuarternly | 2020 e TownCouncil community magazine Photo: Pearl Sandilands 16th ISSUE Folkestone Town Council: 01303 257946 QUALITY GOLD The Town Hall, 1-2 Guildhall Street, Folkestone, CT20 1DY www.folkestonetc.kentparishes.gov.uk “Self storage made easy” • Grade A Security Open 7 Days Free Quotes • • Bu siness & Hou sehold BuTsel:in e01303ss & 850Hou 630sehold www.folkestone-storage.co.ukSelf Storage Self Storage “Self storageWindow made easy” cleaning“Self storage made easy” Local, friendly and reliable service Windows, frames, sills and doors with every clean. Call or text Jeremy 07709119996 Channel Cars Channel Cars We offer a full range of taxis from 4, 5, 6 7, 8 seats, black cabs, eastate cars, saloons and executive cars We now have a number of cars out every night from midnight to 6am We will get you to any destination in the UK, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week Call 01303 252 252 Welcome Happy New Year and welcome to our Spring edition of the Folkestone Town Council Plumbing, Heating, Gas & Building Services • Complete Bathroom Design, Installation & Repairs Community Magazine. Folkestone Town • Central Heating, Installation, Repairs & Upgrades • Unvented Hot Water Systems • Call Outs Council Officers and Councillors hope you had • WIAPS Approved for Mains Water Installation & Repairs a happy and healthy Christmas and New Year. • • Wall & Floor Tiling • Property Maintenance & Building Renovations Folkestone Town Council were once again very Fully insure Free estimates proud of the Christmas light switch on event T: 01303 278292 M: 07798 824538 and amazing fireworks which followed. The www.gsuttonplumbing.co.uk [email protected] crowds gathered from early in the day and • Minor Works enjoyed a variety of activities. -

Folkestone Town Council

FOLKESTONE TOWN COUNCIL ANNUAL REPORT 2019/20 TOWN MAYOR 2019 – 2020 It has been my great honour to serve as Town Mayor of Folkestone this year. It has been a joy to meet and support so many of the wonderful projects, events and charities that make Folkestone so special. Our Museum has gone from strength to strength and has played host to some excellent events including the unveiling of the photograph recreating The Belgian Refugee painting in the Town Hall, where over 200 residents took part showing what a vibrant and welcoming community we are. Folkestone has had some amazing events this year, including Friendship Charter with Mechinager, Nepal; Winner of World Music Town; 25th Royal Gurkha Rifles anniversary attended by Prince Charles; 75th Normandy Veterans Day; Unveiling of the DNA results showing that the skeleton of Aefre, with 98% certainty, is our very own Saint, St Eanswythe; Armed Forces Day with the Red Arrows with over 100,000 attending; Folkestone Trawler Race; Town Hall Christmas Light Switch On with live reindeer and our very own Sandcastle Competition! Due to the Covid-19 restrictions the Town Mayor’s Community Awards have been postponed until later in the year. I would like to thank all the residents who came forward as volunteers during the Covid-19 restrictions and those that self-isolated, to help their friends, neighbours and residents in need - a true community response. I would also like to thank all the key workers who have helped keep us safe and well during this difficult time. My Consort, Bryan, and I have had the pleasure of attending many civic, ceremonial duties and charity fund raising events across the whole of Kent. -

Lower Leas Coastal Park Management Plan 2021 - 2025 CONTENTS

Folkestone & Hythe District Council Lower Leas Coastal Park Management Plan 2021 – 2025 Folkestone & Hythe District Council 1 Lower Leas Coastal Park Management Plan 2021 - 2025 CONTENTS 1 Introduction 4 2 Site Details 5 2.1 Population Distribution 5 2.2 Diverse Countryside 5 2.3 Transport Links 5 2.4 Directions to Coastal Park 5 2.5 Kent Context Map 6 2.6 Folkestone Street Map 6 2.7 Site Description 7 2.8 Aerial Photograph 7 3 Site History 8 3.1 Historical Photographs 9 4 Maintenance Plan 10 4.1 Maintenance Maps 11 4.2 Grounds Maintenance Specification Table 12 4.3 Park Keepers 14 4.4 Engineering and Buildings 15 4.5 Cleansing Contractor 15 4.6 Management Action Plan 16 5 Health and Safety 24 5.1 Introduction 24 5.2 Security 24 5.3 Equipment and Facilities 25 5.4 Chemicals 26 5.5 Vehicles and Machinery 26 5.6 Personal Protection Equipment and Signage 26 6 Facilities 28 6.1 Facilities Maps 28 6.2 Play Area 29 6.3 Amphitheatre 30 6.4 Art 31 6.5 Toilet block 32 6.6 Mermaid Café 33 6.7 Beach Chalets 33 6.8 Picnic Areas 33 6.9 Informal Performance Areas 34 6.10 Gardens 34 6.11 Beach 35 6.12 Cycling 35 6.13 Entrances, Footpaths and Structures 36 7 Nature Conservation and Heritage 37 7.1 Ecological Management 37 7.2 Tree Management 41 7.3 Buildings, Footpaths and Structures 42 Folkestone & Hythe District Council 2 Lower Leas Coastal Park Management Plan 2021 - 2025 8 Sustainability 44 8.1 Green Waste and Composting 44 8.2 Peat 44 8.3 Living Roofs 45 8.4 Waste Management 45 8.5 Tree Stock 45 8.6 Grass Cutting 45 8.7 Furniture and Equipment 45 -

The Roger De Haan Charitable Trust Annual Accounts to April 2017

Charity Registration No. 276274 THE ROGER DE HAAN CHARITABLE TRUST Annual Report and Financial Statements 5'" April 2017 THE ROGER DK HAAN CHARITABLE TRUST Year ended 5 April 2017 CONTENTS Page Legal and administrative information Trustees' annual report Independent Auditors' report Statement of financial activities 15 Balance sheet 16 Statement of cash flows 17 Notes to the accounts THK ROGER DK HAAN CHARITABLE TRUST Year ended 5'" April 2017 LEGAL AND ADMIMSTRATIVK INFORMATION Trustees Sir Roger De Haan (chairman) Benjamin De Haan Joshua De Haan Lady Alison De Haan Address Strand House Pilgrims Way Monks Horton Ashford Kent TN25 6DR Solicitor Withers LLP 16 Old Bailey London EC4M 7EG Banker National Westminster Bank pic Europa House, 49 Sandgate Road Folkestone CT20 1RU Investment Manager UBS 3 Finsbury Avenue London EC2M 2AN Custodian Northern Trust 50 Bank Street Canary Wharf London E14 SNT Auditor Saffery Champness LLP 71 Queen Victoria Street London EC4V 4BE THE ROGER DE HAAiN CHARITABLE TRUST Year ended 5'" April 2017 Trustees' Annual Report The trustees present their audited financial statements for the year ended 5'" April 2017, The financial statements have been prepared in accordance with the Charities Act 2011, and Statement of Recommended Practice "Accounting and Reporting by Charities" applicable to charities preparing their accounts in accordance with the Financial Reporting Standard applicable in the UK and Republic of Ireland (FRS 102) issued on 16 July 2014. Structure, Governance and Management Constitution and Principal Activities The Roger De Haan Charitable Trust (the "Trust"), a registered charity, was established under trust deed on 21 April 1978 (charity number 276274). -

Folkestone and Hythe Birds Tetrad Guide: TR23 H (Mill Point East, Folkestone Harbour and Folkestone Pier)

Folkestone and Hythe Birds Tetrad Guide: TR23 H (Mill Point East, Folkestone Harbour and Folkestone Pier) The coastline is one of the main features within the tetrad, over half of which is comprised by sea. There is a shingle beach which runs from the west end to Folkestone Pier and at low tide a rocky area (Mill Point) is exposed in the western section. Inland of this, in the western half of the tetrad, is the Lower Leas Coastal Park, which extends into the adjacent square. The Coastal Park, which is also known as ‘Mill Point’, has been regularly watched since 1988 and a total of 172 species have been recorded here (the full list is provided at the end of this guide). The Coastal Park was created in 1784 when a landslip produced a new strip of land between the beach and the revised cliff line. In 1828 the Earl of Radnor built a toll road providing an easy route between the harbour and Sandgate and the toll house survives as a private residence within the tetrad. Looking west along Folkestone Beach towards the Lower Leas Coastal Park Looking south-east along Folkestone Pier Either side of the toll road land was cultivated or grazed until in the 1880s pines and Evergreen (Holm) Oaks were planted, being soon followed by self-seeded sycamores, creating a coastal woodland with a lower canopy of hawthorn and ground cover, designed to appeal to visitors to the emerging resort of Folkestone. Access to this wooded area is provided by the toll road and several paths, including the promenade on the Leas which affords good views into the tree tops, where crests, flycatchers and warblers, including Yellow-browed Warbler on occasion, may be seen. -

Folkestone Place Plan Engagement Report

OURPLACE METHODOLOGY PLAN FOR FOLKESTONEAND RESPONSE TOWN CENTRE TITLEAPPENDIX SPLIT 2 -OVER ENGAGEMENT TWO LINES REPORT - REVISION A - 06-08-2021 CONTENTS 1.0 Who have we spoken to and how? p3 — 1.1: Who have we spoken to? — 1.2: Engagement contacts log — 1.3: How have we engaged? 2.0 Stakeholder conversations p9 — 2.1: One-to-one conversations — 2.2: Stakeholder workshops 3.0 Wider public engagement p14 — 3.1: Virtual webinar 1 — 3.2: Virtual webinar 2 — 3.3: Equality, Diversity & Inclusion — 3.4 Website and Communications Revisions tracker Rev. Date Description - 07-07-2021 Draft for comment A 06-08-2021 Revision A issue for Cabinet Place Plan for Folkestone Town Centre Appendix p 2 © VVE MADE THAT 1.0 WHO HAVE WE SPOKEN TO AND HOW? HELP SHAPE THE FUTURE OF FOLKESTONE TOWN CENTRE Please join us to meet the team and hear about the emerging ideas, priorities & vision for the Town Centre Place Plan. The Place Plan will set clear ‘missions’ and propose specific actions to help shape the future of Folkestone’s Town Centre. This is a chance to share your views and ask us any questions you have. Everyone is invited to take part, so please do share with your contacts and networks. HOW TO GET INVOLVED To sign up for the webinar please visit: folkestone-hythe.gov.uk/folkestoneplaceplan If you have any questions, contact: [email protected] Please note: a survey and printed pack will be made available for those who do not have online access. WEBINAR This can be requested by calling Folkestone & Hythe MONDAY District Council on +44 -

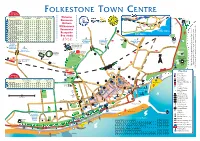

Folkestone-Map.Pdf

OLKESTONE OWN ENTRE Walking F T C Time Guide A 2 A 6 11 Channel Tunnel 2 0 0 Attraction from Folkestone from Sandgate from Harbour 20 13 59 2 Welcome M A B 12 2 Central Rail Road Approach A20 6 11A 0 12 1 Kingsnorth Gardens 2 mins 10 mins 17 mins Bienvenue M20 Martello 9 A20 Tower 2 The Bandstand 15 mins 9 mins 15 mins A203 25 A No.1 4 Folkestone 3 Coastal Playground 20 mins 10 mins 12 mins Welkom A20 34 Central B P 4 The Leas 15 mins 2 mins 9 mins Folkestone 2 West 064 A2034 5 Coastal Path 20 mins 7 mins 10 mins Willkommen B2063 3 6 The Leas Lift 15 mins 3 mins 10 mins Benvenuto A259 A203 7 St Eanswythes Church 15 mins 1 min 5 mins A259 Folkestone 8 The Old High Street 15 mins 2 mins 0 min Recepción 9 Folkestone Harbour 20 mins 8 mins 2 mins Sandgate3 0 Playing Boa vinda 0 10 Sunny Sands 20 mins 7 mins 3 mins 2 Field A 11 Martello Tower 30 mins 22 mins 16 mins Salvation D Retail Park To Canterbury To A 12 The Warren 35 mins 27 mins 21 mins 9 Army O 5 Martello VENUE & Folkestone & Hawkinge Capel Le Ferne R A 2 Tower Academy A Rec. CA & Dover (Battle of Britain N ER No.2 N TE To M20 Folkestone Sports Centre Museum) D Park RB DE A U OV Junction 12 R with Swimming Pools, RY RK FARM ROAD FARM RK D A O R VEN Dry Ski Slope and A R D D A UE Cheriton & . -

Grants and Partnership Register December 2020

FOLKESTONE & HYTHE * Company/Charity DISTRICT COUNCIL Registration if applicable Corporate Partnership Register 31st December 2020 FHDC Partnership Name Date Partnership End Date/ Review Activities Service Area contribution [Registration*] Formed Date (>£5000) Working with people to maintain and White Cliffs and Romney Marsh improve key areas/Conservation - Countryside Partnerships Economic Development 1989 Ongoing £40,360.00 Folkestone Downs and Warren, [DDC Lead Authority] Dungeness, Romney Warren etc Kent Connects Provision of shared network for local Legal and Democratic 2003 Ongoing £20,000.00 [KCC Organised] government in Kent Services BOSCO (Boulogne and Shepway Co- Transfrontier association between Operation) Economic Development 2002 Mar-21 £4,630.00 Boulogne and Shepway [TBC (French legal entity)] Kent Wildlife Trust (Romney Warren Grant to support the Romney Marsh Country Park) Visitor Centre and Romney Warren Economic Development 2004 Ongoing £9,950 [Reg. charity No: 239992] Country Park Meets priorities set out in CSP partnership Folkestone & Hythe Community Safety £10,000 plan, to include:- ASB/Substance misuse Partnership Communities 1998/9 Ongoing (statutory duty) (for IDVA provision and small projects, Domestic abuse initiatives, [FHDC Accountable Body] project contributions) tackling Envirocrime. FHDC Partnership Name Date Partnership End Date/ Review Activities Service Area contribution [Registration*] Formed Date (>£5000) Folkestone & Hythe Tenants and Stakeholder Engagement Communities 2011 (current agreement) Ongoing £5,000.00 Leaseholders Board (STLB)/Area Board Kent Resource Partnership (including Kent Waste Forum) Improve waste management across Kent. Strategic Operations 2009 2021 £5,000.00 [County & Districts] East Kent Waste Partnership incorporating Joint Working Agreement Management of the waste, recycling and Strategic Operations 2012 Ongoing £168,000.00 [Joint Partnership - KCC, FHDC and street cleansing contract. -

Annual Report 2020/21

ANNUAL REPORT 2020/21 J Childs FOLKESTONE TOWN COUNCIL Table of Contents TOWN MAYOR 2020 - 2021 ........................................................................................................................................................................ 3 INCOME AND EXPENDITURE ACCOUNT ................................................................................................................................................. 5 For the Period ended 31 March 2021 ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 Balance Sheet as at 31 March 2021 ......................................................................................................................................................... 7 THE TOWN COUNCIL’S MISSION .............................................................................................................................................................. 9 Future Events and Notes for your Diary .................................................................................................................................................. 10 COUNCIL STRUCTURE ............................................................................................................................................................................ 11 Committee Meetings 2021/22 ................................................................................................................................................................ -

FOLKESTONE COASTAL COMMUNITY TEAM ECONOMIC PLAN Local Area Folkestone Is a Coastal Town of National Strategic Importance with Undoubted Potential

FOLKESTONE COASTAL COMMUNITY TEAM ECONOMIC PLAN Local Area Folkestone is a coastal town of national strategic importance with undoubted potential. Its location on the south Kent coast places the town in an enviable position, with unparalleled scenery and outstanding transport infrastructure which links it to the rest of the UK and to Europe. Like a number of once prosperous coastal resorts, Folkestone has been evolving over Ambition for the town has remained strong in spite of numerous severe economic the last 40 years to find a new role and purpose and, thereby, real prosperity for its challenges and since 2004 a concerted strategy has been developed to regenerate key residents. Key to a more successful future is driving forward economic regeneration, areas of the Old Town, to bring about major improvements in education provision and by bringing together public, private and business expertise. to establish new opportunities for the enjoyment of residents and visitors in art and sports. In addition, in September 2009, Folkestone’s two railway stations began to offer Folkestone is a town with a proud history closely linked to the growth of Great Britain high speed services to London St Pancras in a little over 50 minutes. In terms of road as a nation through its proximity to the Continent, beginning in the Iron Age, the transport the town benefits from direct access to the motorway network with Junctions Romans, the Saxons, then the Normans, by which time the original fishing village had 12 and 13 of the M20. These recent developments have begun to stimulate greater become part of the Cinque Ports federation. -

The Darling Buds of May 8Pp A5 Brochure

j Experience The the Garden Darling of england - s perfick! Budsj of Mayj j The s Good food,good friends,love,laughter Darling and beautifulcountryside: TV series, It’s no coincidencethat Kentish food The Darling Buds of May,captures life and producealso playa starring Budsof role inThe Darling Buds of May. j inan idyllic rural,1950s Kent,where Mayj lifewiththe Larkin familyis never dull. The Darling Buds of Mayseries capturesthe Kentwayof life,and The series was based on a novel of When it first aired in 1991, the feel-good the same name by author H.E. Bates. show was an instant hit and it took top position the enjoyment of localproduce is He was born in Northamptonshire, in the overnight ratings. Three series later verymuch part ofthat. One ofthe Kent’s association with growing hops has Main cast infront of table © ITV but it was Kent that captured his it became a firm favourite nationwide.To this earliest episodes showsthe Larkin led to oast houses becoming an instantly heart when he moved to Little day the series has remained in the hearts of recognisable symbol of the county and in women picking strawberries,and Chart with his wife in 1930. audiences as well as the hearts of the the 19th and early 20th centuries, 80,000 t s Pluckley locals, who still enjoy fond memories a major storyline sees Marietteand people would have been involved in the It was some years later when the author of seeing the filming and being involved. Charley go onto buya hop garden annual harvest at hop-picking time in and his wife stopped at a village shop September. -

Folkestone & Hythe District Council Lower Leas Coastal Park

Folkestone & Hythe District Council Lower Leas Coastal Park Management Plan 2016 – 2020 Folkestone & Hythe District Council 1 Lower Leas Coastal Park Management Plan 2016 - 2020 CONTENTS 1 Introduction 4 2 Site Details 5 2.1 Population Distribution 5 2.2 Diverse Countryside 5 2.3 Transport Links 5 2.4 Directions to Coastal Park 6 2.5 Kent Context Map 6 2.6 Folkestone Street Map 7 2.7 Site Description 7 2.8 Aerial Photograph 8 2.9 Places Maps 9 3 Site History 11 3.1 Historical Photographs 12 4 Maintenance Plan 14 4.1 Maintenance Maps 15 4.2 Grounds Maintenance 17 4.3 Park Keepers 19 4.4 Property 20 4.5 Engineers 21 4.6 Regeneration 21 4.7 Cleansing Contractor 21 4.8 Management Plan Summary Table 21 5 Health and Safety 30 5.1 Introduction 30 5.2 Security 31 5.3 Equipment and Facilities 31 5.4 Chemicals 32 5.5 Vehicles and Machinery 33 5.6 Personal Protection Equipment and Signage 33 6 Facilities 34 6.1 Play Area 34 6.2 Amphitheatre 35 6.3 Toilet Block 35 6.4 Mermaid Café 36 6.5 Beach Chalets 36 6.6 Picnic Areas 36 6.7 Informal Performance Areas 34 6.8 Gardens 37 6.9 Beach 38 6.10 National Cycle Route 2 39 7 Nature Conservation and Heritage 40 Folkestone & Hythe District Council 2 Lower Leas Coastal Park Management Plan 2016 - 2020 7.1 Ecological Management 40 7.2 Buildings Footpaths and Structures 41 8 Sustainability 44 8.1 Vehicles and Machinery 44 8.2 Recycling 45 8.3 Horticulture 45 8.4 Furniture 47 9 Marketing 47 9.1 Leaflet 47 9.2 Facebook 47 9.3 Visitor Survey 47 9.4 Interpretation and Signage 48 9.5 Web Advertising 49 9.6 Business Engagement and Shows 49 9.7 In House Promotion 49 9.8 Publications 49 10 Community Involvement 50 10.1 Events Process 50 10.2 User Groups 51 10.3 Art 52 10.4 Volunteers 53 11 List of Appendices 54 Folkestone & Hythe District Council 3 Lower Leas Coastal Park Management Plan 2016 - 2020 1 Introduction ______________________________________________________________ The Coastal Park has seen major investment by Folkestone & Hythe District Council (FHDC) and other funding bodies since 1999.