Accurate Reconstruction of the Roman Circus in Milan by Georeferencing Heterogeneous Data Sources with GIS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Environmental Suppliers Customer and Citizens Institutions and Communities Susainability Report - 2012 1 Index

Sustainability Report 2012 employees shareholders and investors environmental suppliers customer and citizens institutions and communities Susainability report - 2012 1 Index Index Letter to stakeholders 4 Introduction and note on methodology 6 The A2A Group’s Sustainability Report 6 Methodology 6 Scoping logic 7 Materiality 9 1 The A2A group 10 1.1 Size of the organisation and markets served 14 1.2 Companies outside the consolidation scope 15 2 Strategies and policies for sustainability 17 2.1 Mission and vision 18 2.2 Commitments and objectives for the future 18 2.3 The 2013-2015 Sustainability Plan and key indicators/results achieved in 2012 19 2.4 Partnerships and awards for sustainability 25 2.5 Corporate governance 27 Corporate governance bodies 27 Corporate governance tools 34 Regulatory framework 35 2.6 Stakeholder chart and engagement initiatives 37 3 Economic responsibility 41 3.1 The Group’s 2012 results 43 3.2 Formation of Value Added 43 3.3 Distribution of Net Global Value Added 45 3.4 Capital expenditure 46 3.5 Shareholders and Investors 47 Composition of share capital 47 A2A in the stock exchange indices 48 A2A in the sustainability ratings 49 2 Susainability report - 2012 Index Investing in A2A: sustainability as a valuation project 49 Relations with shareholders and investors 52 3.6 Tables: the numbers of the A2A Group 55 4 Environmental responsibility 57 4.1 Managing the environment 58 Environmental policy 59 Environmental management system 59 Environmental risk management 60 Environmental accounting 61 Research and -

New Milan Fair Complex

NEW MILAN FAIR COMPLEX Milan, Italy Development Team The New Milan Fair Complex (Nuovo Sistema Fiera Milano) has transformed a brownfield site along the Owner/Developer main road from downtown Milan to Malpensa Airport into a 200-hectare (494 ac) exhibition center, re- lieving traffic congestion around the historic fairground in the city center and allowing the original fair- Fondazione Fiera Milano Milan, Italy ground to continue to host smaller congresses and trade shows, even after part of the downtown site is www.fondazionefieramilano.com sold and redeveloped. The two separate yet complementary developments—the new complex at Rho- Pero (popularly known as Fieramilano) and the downtown complex (known as Fieramilanocity)—have Architect brought new life and prestige to Milan’s exhibition industry, enabling the Milan Fair Complex to con- Massimiliano Fuksas architetto tinue competing with other European exhibition centers and to maintain its position as an international Rome, Italy leader. Both projects are being promoted by Fondazione Fiera Milano, the private company that owns www.fuksas.it and operates the Milan Fair Complex, through its subsidiary Sviluppo Sistema Fiera SpA. Associate Architects The site of the new complex at Rho-Pero, two adjoining industrial suburbs northwest of Milan, was Schlaich Bergermann und Partner long occupied by an Agip oil refinery. After Fondazione Fiera Milano purchased the site, the refinery was Stuttgart, Germany dismantled and the land and groundwater cleaned up. In an approach considered highly unusual and www.sbp.de innovative in Italy, the foundation issued an international request for proposals (RFP) to select a general Studio Altieri contractor, an approach that lent continuity and consistency to the design and construction stages and Thiene (VI), Italy resulted in more accurate cost estimates and quicker completion. -

Milan, Italy Faculty Led Learning Abroad Program Fashion and Design Retailing: the Italian Way Led By: Dr

Milan, Italy Faculty Led Learning Abroad Program Fashion and Design Retailing: The Italian Way Led by: Dr. Chiara Colombi & Dr. Marcella Norwood What: 10-Day Study Tour: Milan, Italy (including Florence, Italy) When: Dates: May 22 – 31, 2016 (Between spring and summer terms 2016) Academic Plan: 1. Participate in preparation series during spring 2016 2. Travel & tour 3. Complete written assignments Enrollment: Enroll in HDCS 4398 or GRET 6398 (summer mini session) GPA Requirement: 2.5 (undergraduates); 3.0 (graduates) Scholarships: UH International Education Fee Scholarships 1. $750 (see http://www.uh.edu/learningabroad/scholarships/uh- scholarships/ for eligibility and application details. (graduate students already receiving GTF not eligible for scholarship) Deadline: IEF scholarship applications open January 4, close March 4. http://www.uh.edu/learningabroad/scholarships/uh-scholarships/) 2. $250 tuition rebate for HDCS 4398 (see http://www.uh.edu/learningabroad/scholarships/uh-scholarships/) (not available for GRET 6398 enrollment) To Apply: For Study Tour: To go into the registration, please click on this link (www.worldstridescapstone.org/register ) and you will be taken to the main registration web page. You will then be prompted to enter the University of Houston’s Trip ID: 129687 . Once you enter the Trip ID and requested security characters, click on the ‘Register Now’ box below and you will be taken directly to the site . Review the summary page and click ‘Register’ in the top right corner to enter your information 1 . Note: You are required to accept WorldStrides Capstone programs terms and conditions and click “check-out” before your registration is complete. -

Milan's New Exhibition System: a Driving Force Behind

COMUNICATO STAMPA MILAN’S NEW EXHIBITION SYSTEM: A DRIVING FORCE BEHIND THE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT OF LOMBARDY AND ITALY AS A WHOLE Monday, 17 November 2003 – Total revenues of more than €4.3 billion versus €2 billion in 2000, and 42,743 new jobs. This is the positive impact that Milan Fair will have on the regional economy when Milan’s new exhibition system, comprising the New Complex and the City Complex, will be operating at full capacity. Above, are some of the findings of a study conducted by Fondazione Fiera Milano – Ufficio Studi - in concert with CERTeT of Bocconi University, that will be presented on Friday, 14 November at the Milan conference of the “East-West Lombardy – the cardinal points of development” roadshow. The New Complex – the first stone of which was laid on 6 October 2002 – is a project that is being fully self-funded by Fondazione Fiera Milano and involves an investment of approx. €750 million, which includes the cost of purchasing the sites. The New Complex will have a gross floorspace of 530,000 square meters on a 2-million square meter site. A major project that is being developed by a private entity – Fondazione Fiera Milano – but with positive fallout for the public, the construction of which will generate €835 million in revenues and 7,900 new jobs. Noteworthy are also the figures related to the redevelopment project associated with the New Complex, with approx. 4.5 million cubic meters of reclaimed land. The study also shows that housing values in the municipalities around the New Complex rose - during 2000/2003 - by 25 percent versus 14.5 percent of comparable areas in the first city belt. -

Pagan-City-And-Christian-Capital-Rome-In-The-Fourth-Century-2000.Pdf

OXFORDCLASSICALMONOGRAPHS Published under the supervision of a Committee of the Faculty of Literae Humaniores in the University of Oxford The aim of the Oxford Classical Monographs series (which replaces the Oxford Classical and Philosophical Monographs) is to publish books based on the best theses on Greek and Latin literature, ancient history, and ancient philosophy examined by the Faculty Board of Literae Humaniores. Pagan City and Christian Capital Rome in the Fourth Century JOHNR.CURRAN CLARENDON PRESS ´ OXFORD 2000 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's aim of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogota Bombay Buenos Aires Calcutta Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris SaÄo Paulo Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw with associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York # John Curran 2000 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2000 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organizations. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same conditions on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data applied for Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Curran, John R. -

9781107013995 Index.Pdf

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01399-5 — Rome Rabun Taylor , Katherine Rinne , Spiro Kostof Index More Information INDEX abitato , 209 , 253 , 255 , 264 , 273 , 281 , 286 , 288 , cura(tor) aquarum (et Miniciae) , water 290 , 319 commission later merged with administration, ancient. See also Agrippa ; grain distribution authority, 40 , archives ; banishment and 47 , 97 , 113 , 115 , 116 – 17 , 124 . sequestration ; libraries ; maps ; See also Frontinus, Sextus Julius ; regions ( regiones ) ; taxes, tarif s, water supply ; aqueducts; etc. customs, and fees ; warehouses ; cura(tor) operum maximorum (commission of wharves monumental works), 162 Augustan reorganization of, 40 – 41 , cura(tor) riparum et alvei Tiberis (commission 47 – 48 of the Tiber), 51 censuses and public surveys, 19 , 24 , 82 , cura(tor) viarum (roads commission), 48 114 – 17 , 122 , 125 magistrates of the vici ( vicomagistri ), 48 , 91 codes, laws, and restrictions, 27 , 29 , 47 , Praetorian Prefect and Guard, 60 , 96 , 99 , 63 – 65 , 114 , 162 101 , 115 , 116 , 135 , 139 , 154 . See also against permanent theaters, 57 – 58 Castra Praetoria of burial, 37 , 117 – 20 , 128 , 154 , 187 urban prefect and prefecture, 76 , 116 , 124 , districts and boundaries, 41 , 45 , 49 , 135 , 139 , 163 , 166 , 171 67 – 69 , 116 , 128 . See also vigiles (i re brigade), 66 , 85 , 96 , 116 , pomerium ; regions ( regiones ) ; vici ; 122 , 124 Aurelian Wall ; Leonine Wall ; police and policing, 5 , 100 , 114 – 16 , 122 , wharves 144 , 171 grain, l our, or bread procurement and Severan reorganization of, 96 – 98 distribution, 27 , 89 , 96 – 100 , staf and minor oi cials, 48 , 91 , 116 , 126 , 175 , 215 102 , 115 , 117 , 124 , 166 , 171 , 177 , zones and zoning, 6 , 38 , 84 , 85 , 126 , 127 182 , 184 – 85 administration, medieval frumentationes , 46 , 97 charitable institutions, 158 , 169 , 179 – 87 , 191 , headquarters of administrative oi ces, 81 , 85 , 201 , 299 114 – 17 , 214 Church. -

Timeline / 1890 to 1900 / ITALY

Timeline / 1890 to 1900 / ITALY Date Country Theme 1890 - 1899 Italy Migrations Average annual Italian migration (temporary and permanent, to nearest 1,000): France 26,000, USA 51,000; Argentina 37,000; Brazil 58,000. 1890 Italy Music, Literature, Dance And Fashion The Cavalleria rusticana by Pietro Mascagni (1863–1945) has a great success, marking the beginning of verismo (Italian realism) in music, which intends to portray the world of peasants and the poor through strong and passionate drama. The singing style changes radically, leaving behind the aesthetics of bel canto and turning to reciting, even shouting, and spoken parts in the most exciting dramatic moments. 1890 Italy Reforms And Social Changes For the first time, trade unions organise celebrations for May Day as the International Worker’s Day. 1891 Italy Reforms And Social Changes First Chambers of Labour (territorial trade unions) founded in Milan. 1892 Italy Political Context Italian Socialist Party founded. 1892 - 1898 Italy Great Inventions Of The 19th Century Hydroelectric power plants are built in Tivoli (1892) and Paderno d’Adda (1898) and the power they generated is transported to, respectively, Rome and Milan. 1893 - 1895 Italy Cities And Urban Spaces Construction of Piazza Vittorio Emanuele (today Piazza della Repubblica) in Florence, after clearing the area of the Ancient Market. 1893 - 1894 Italy Economy And Trade A comprehensive law on banking establishes the Bank of Italy, which starts operating on 1 January 1894. 1893 Italy Music, Literature, Dance And Fashion Manon Lescaut by Giacomo Puccini (1858–1924) has a great success in Turin and Puccini becomes the most promising opera composer of the new generation. -

Rome Milan Sokol Ft

April 2021 Quarterly Publication AMERICAN SOKOL TYRS Honor Award Presented to Rome Milan Sokol Ft. Worth For Leadership in the Sport of Gymnastics And Selfless Dedication to Sokol In the True Spirit of its Founder Miroslav Tyrs The Falcon is the fastest bird of flight at 200 miles per hour and vision 2.5 times greater than humans. Fly you Sokol, fly on high! 1 Board of Governors The Sokol Eye – Sokolským Okem President Jean Hruby March/April 2021 Districts: Jean Hruby – President Central Rich Vachata A true legacy of Sokol, gymnastic pioneer, champion, innovator, mentor, Eastern Irene Wynnyczuk trendsetter…these are the qualities of the American Sokol Hall of Fame Dr. Northeastern Meg Novacek Miroslav Tyrš Honor Award. Pacific Yvonne Masopust This month the Southern District honored Brother Rome Milan with this notable Southern Robert Podhrasky award. When Rome Milan established the American Sokol Hall of Fame Awards, Western Allison Gerber he had a vision to remember those who have made a mark and changed the history of Sokol in a positive way. Unaware, Rome was actually writing his own history. Executive Board Members Together on “Zoom” many Sokols from around the USA joined the Southern President Jean Hruby District to witness Rome receiving this prestigious award. Listening to all of Rome’s accomplishments, memories and the words of gratitude shared by many 1st VP Robert Podhrasky who joined, reminded this “Sokol Eye” that we have remarkable people in our 2nd VP Maryann Fiordelis family and that if we strive to be like Rome Milan, Sokol will carry on. -

For an Urban History of Milan, Italy: the Role Of

FOR AN URBAN HISTORY OF MILAN, ITALY: THE ROLE OF GISCIENCE DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of Texas State University‐San Marcos in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of PHILOSOPHY by Michele Tucci, B.S., M.S. San Marcos, Texas May 2011 FOR AN URBAN HISTORY OF MILAN, ITALY: THE ROLE OF GISCIENCE Committee Members Approved: ________________________________ Alberto Giordano ________________________________ Sven Fuhrmann ________________________________ Yongmei Lu ________________________________ Rocco W. Ronza Approved: ______________________________________ J. Micheal Willoughby Dean of the Gradute Collage COPYRIGHT by Michele Tucci 2011 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My sincere thanks go to all those people who spent their time and effort to help me complete my studies. My dissertation committee at Texas State University‐San Marcos: Dr. Yongmei Lu who, as a professor first and as a researcher in a project we worked together then, improved and stimulated my knowledge and understanding of quantitative analysis; Dr. Sven Fuhrmann who, in many occasions, transmitted me his passion about cartography, computer cartography and geovisualization; Dr. Rocco W. Ronza who provided keen insight into my topic and valuable suggestions about historical literature; and especially Dr. Alberto Giordano, my dissertation advisor, who, with patience and determination, walked me through this process and taught me the real essence of conducting scientific research. Additional thanks are extended to several members of the stuff at the Geography Department at Texas State University‐San Marcos: Allison Glass‐Smith, Angelika Wahl and Pat Hell‐Jones whose precious suggestions and help in solving bureaucratic issues was fundamental to complete the program. My office mates Matthew Connolly and Christi Townsend for their cathartic function in listening and sharing both good thought and sometimes frustrations of being a doctoral student. -

Roman Architecture Mini Guide

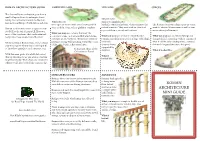

ROMAN ARCHITECTURE GUIDE AMPHITHEATRE THEATRE CIRCUS The Ancient Rome civilization grew from a small village in Rome to an Empire domi- Theatres were nating vast territories around the Mediter- similar to Amphitheatres ranean Sea in Europe, North Africa and Asia. Amphitheatres but had a semicircular form, which enhances the The Roman circus was a large open-air venue were open air venues with raised seating which natural acoustics. They were used for theatrical used for chariot & horse races as well as com- Roman Architecture covers the period from were used for event such as gladiator combats. representation, concerts and orations. memoration performances. 509 BCE to the 4th Century CE. However, most of the structures, that can be admired What you may see: remains that look like What you may see: similar to Amphitheatres What you may see: an extremely large and today dates from around 100 CE or later. concentric stairs ; a downward hill which forms a circular or an oval basin ; Remains of arches or remains; raised flat area used as a stage with a high elongated field ; encircling walls or remains of back wall what look like stairs (seating area) ; a central When looking at Roman ruins, it’s not always passages ; strong walls pointing toward the center (scaenae frons) thin and elongated structure (the spina). easy to recognize what you are looking at & of the basin ; a flat central area. supported by to know how grandiose such structure was. In that case, think of the columns. What it looked like : Colosseum in Rome! With this mini guide, it is a little bit easier! What it The top drawing shows you what a structure looked like : might look today. -

A Contemporary View of Ancient Factions: a Reappraisal

A Contemporary View of Ancient Factions: A Reappraisal by Anthony Lawrence Villa Bryk A thesis presented for the B.A. degree with Honors in The Department of Classical Studies University of Michigan Spring 2012 i “Ab educatore, ne in circo spectator Prasianus aut Venetianus neve parmularius aut scutarius fierem, ut labores sustinerem, paucis indigerem, ipse operi manus admoverem, rerum alienarum non essem curiosus nec facile delationem admitterem.” “From my governor, to be neither of the green nor of the blue party at the games in the Circus, nor a partizan either of the Parmularius or the Scutarius at the gladiators' fights; from him too I learned endurance of labour, and to want little, and to work with my own hands, and not to meddle with other people's affairs, and not to be ready to listen to slander.” -Marcus Aurelius, Meditations, 1.5 © Anthony Lawrence Villa Bryk 2012 ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Professor David S. Potter for his wisdom, guidance, and patience. Professor Potter spent a great deal of time with me on this thesis and was truly committed to helping me succeed. I could not have written this analysis without his generous mentoring, and I am deeply grateful to him. I would also like to thank Professor Netta Berlin for her cheerful guidance throughout this entire thesis process. Particularly, I found her careful editing of my first chapter immensely helpful. Also, Professor Sara Ahbel-Rappe’s Pagans and Christians seminar was essential to my foundational understanding of this subject. I also thank her for being a second reader on this paper and for suggesting valuable revisions. -

Fik Meijer, Chariot Racing in the Roman Empire (Translated by Liz Waters)

Fik Meijer, Chariot Racing in the Roman Empire (translated by Liz Waters). Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010. Pp. xiv, 185. ISBN- 13:978-0-8018-9697-2 (HB). $29.95 (pb). This book is an accessible and interesting introduction to the topic, which for the most part is grounded in good scholarship. Meijer’s introduction brings to life the Roman love of chariot racing exhibited by both elites and the common people. Just as successful in this regard are Chapters 5 (“A Day at the Circus Maximus”) and 7 (“The Spectators”). In the former, translated passages from Ovid and Sidonius Apollinaris put the reader in a seat in a Roman circus, while the latter deals with other aspects of the spectators’ experience: for example, their communications with the emperor, their fanatical identification with the colors of the four racing factions, curse tablets inscribed by fans asking demonic gods to harm opposing charioteers and horses, gambling, and crowd violence. Chapters 3 (“The Circus Maximus”), 4 (“Preparation and Organization”), and 6 (“The Heroes of the Arena”) complete his discussion of the Circus Maximus. Chapter 2 (“Chariot Races of the First Century BC and Earlier”) begins with the military use of chariots by the Egyptians, Hittites and Mycenaeans. M. points out that it is not clear whether these peoples ever used chariots for racing. He then proceeds to the first unambiguous appearance of the sport, in archaic Greece (Homer and the Olympic Games), and finishes with the earliest evidence for it at Rome from the regal period down to the late Republic.