The Long Roll

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Die 11 Lieder Von Jenny Evans' CD Christmas Songs Sind Weit Entfernt

CHRISTMAS SONGS ENJ-9481 2 Heart warming Christmas Songs – the title is not quite as original as the music behind it. In comparison to Diana Krall’s CD Jenny Evans offers more unexpected tones. Her repertoire coincides with her Canadian colleague in two numbers („The Christmas Song“, „Have Yourself A Merry Little Christmas“) but apart from that the English woman who lives in Munich gives her Christmas album a definite European touch. Most noticably in her choice of material: she’s searched through Eruopean folk tunes and as well as English has also discovered German, Austrian and Czech songs that have never been rendered in a jazzy way. Some go backe to the 16th century (e.g. „The Coventry Carol“) for Jenny Evans, who started her career with piano lessons with the Baroque specialist Trevor Pinnock, then sang with the Henrich Schütz Choir and the Munich Motettenchor an ideal area to merge her love of Early Music with jazz by no means stretches the bow too far. She gives a a latin groove to “Blessed Be That Maid Mary” with its Latin and English lyrics, her own lyrics and an Akro-Cuban rhythm to a Czech Christmas lullaby and the Austrian “Still, still, still“ a world music touch with drone and yodelling. When she does go turn to the American repertoire whtn it is with a medley of two popular standards (“Little Drummer Boy / Nature Boy”) that have never been heard together. With her dulcet voice this vocalist can warm your heart and that is the main thing at this season. -

Offical File-Christmas Songs

1 The History and Origin of Christmas Music (Carol: French = dancing around in a circle.) Table of Contents Preface 3 Most Performed Christmas Songs 4 The Christmas Song 5 White Christmas 5 Santa Claus is Coming to Town 6 Winter Wonderland 7 Have Yourself a Merry Christmas 8 Sleigh Ride 9 Rudolph the Red Nosed Reindeer 10 My Two Front Teeth 11 Blue Christmas 11 Little Drummer Boy 11 Here Comes Santa Claus 12 Frosty the Snowman 13 Jingle Bells 13 Let it Snow 15 I’ll Be Home for Christmas 15 Silver Bells 17 Beginning to Look Like Christmas 18 Jingle Bell Rock 18 Rockin’ Round Christmas Tree 19 Up on the Housetop 19 Religious Carols Silent Night 20 O Holy Night 22 O Come All Ye Faithful 24 How firm A Foundation 26 Angels We Have Heard on High 27 O Come Emmanuel 28 We Three Kings 30 It Came Upon a Midnight Clear 31 Hark the Herald Angels Sing 33 The First Noel 34 The 12 Days of Christmas 36 God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen 36 Lo How A Rose E’er Blooming 39 Joy to the World 39 Away in a Manger 41 O Little Town of Bethlehem 44 Coventry Carol 46 2 Good King Wenceslas 46 I Saw Three Ships 48 Greensleeves 49 I Heard the Bells/Christmas Day 50 Deck the Hall 52 Carol of the Bells 53 Do You Hear What I Hear 55 Birthday of a King 56 Wassil Song 57 Go Tell it on the Mountain 58 O Tannanbaum 59 Holly and the Ivy 60 Echo Carol 61 Wish You a Merry Christmas 62 Ding Dong Merrily Along 63 I Wonder as I Wander 64 Patapatapan 65 While Shepherds Watch Their Flocks by Night 66 Auld Lang Syne 68 Over the River, thru the Woods 68 Wonderful time of the Year 70 A Little Boy Came to Bethlehem To Bethlehem Town 70 Appendix I (Jewish composers Of Holiday Music 72 Preface In their earliest beginning the early carols had nothing to do with Christmas or the Holiday season. -

Jazz Lines Publications Silent Night Presents Arranged by Wynton Marsalis Full Score

Jazz Lines Publications Silent Night Presents Arranged by wynton marsalis full score jlp-7204 Words by Joseph Mohr, Music by Franz Gruber Copyright © 1989 SKAYNES MUSIC International Copyright Secured All Rights Reserved Used by Permission Logos, Graphics, and Layout Copyright © 2014 The Jazz Lines Foundation Inc. This Arrangement Has Been Published with the Authorization of Wynton Marsalis Published by the Jazz Lines Foundation Inc., a not-for-profit jazz research organization dedicated to preserving and promoting America’s musical heritage. The Jazz Lines Foundation Inc. PO Box 1236 Saratoga Springs NY 12866 USA wynton marsalis series Silent night (1989) Background (from the liner notes to the album): As might be expected, the joy, reverence, play, and humor associated with the Christmas season dominate the moods of this Wynton Marsalis album. But the ease and precision with which a down-home and elegant victory has been achieved over the large challenge of arranging such familiar material will surprise even seasoned Marsalis listeners. What amounts to the thematic and emotional folklore of the winter holidays has been fused with the clarity of passion and musical sophistication expected of the best of the jazz tradition. Here the talent for composition, arranging, and recasting that Wynton Marsalis has been diligently expanding upon since his very first album as a leader proves itself to have arrived at yet another fresh point of expressiveness. And as with all complete artistic achievements, it results from the seamless interweaving of the aesthetic and the personal. “For at least five years,” says Marsalis, “I have wanted to do a Christmas album. -

Immaculate Heart of Mary Catholic Church the Little Drummer

Immaculate HeartThe Epiphany of Mary of the Catholic Lords, January Church 7, 2018 Mailing Address: P. O. Box 100 * New Melle, MO 63365 Website: www.ihm-newmelle.org Deliveries only address: 8 West Highway D, New Melle, MO 63365 Parish Office: 636-398-5270 Fax: 636-398-5577 Schedule of Holy Mass The Epiphany of the Lord Saturday: 8:00am 4:00pm Vigil Mass for Sunday January 7, 2018 Sunday: 7:30am, 9:30am Weekdays: 8:00am, St. Joseph Chapel Weekly Devotions and Prayers Eucharistic Adoration: Monday 8:30am until Friday, 11:30am Rosary: Following 8am Mass Monday thru Friday Perpetual Help Devotions: Tuesdays following 8am Mass Respect Life Prayers: Thursday following 8am Mass Chaplet of Divine Mercy and Benediction: Friday at 11:30am First Saturday of the Month Devotions 8am Mass, Rosary, 15 minutes of meditation Sacraments Reconciliation: Wednesday in church, 7pm Saturday following 8am Mass Marriage: Contact the parish office at least six months prior to the wedding Baptism: Contact the parish office to register for class and to arrange date Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults: Contact Shawn Mueller in the parish office The Little Drummer Boy Did you know that the only rea- men paying homage to Jesus’ divinity. Mass, others spend time in adoration son we say that there were three wise The gift of myrrh is oil used to anoint before the Eucharist, or even a few men is that they brought three gifts? the dying. It reminds us of Jesus suf- minutes of their lunch break to say the The Bible never says their number or fering and death on the cross. -

Luke 1:39-55 December 23, '18 “PLAY IT AGAIN, MARY” DURING

Luke 1:39-55 December 23, ‘18 “PLAY IT AGAIN, MARY” DURING ADVENT THIS YEAR, WE’RE LOOKING AT “SECULAR CHRISTMAS, SONGS, BOOKS & MOVIES THAT SPEAK TO THE SOUL.” WE’VE LOOKED AT STEVIE WONDER’S “SOMEDAY AT CHRISTMAS,” “RUDOLPH THE RED-NOSED REINDEER” & CHARLES DICKENS’ “A CHRISTMAS CAROL.” THIS MORNING, OUR CHOICE DOESN’T REALLY FALL NEATLY IN LINE WITH THE REST OF THE SERIES FOR AT LEAST A COUPLE OF REASONS. FOR ONE THING, WE’VE ALREADY DONE A SONG & FOR ANOTHER, OUR CHOICE HARDLY QUALIFIES AS SECULAR! WHEN THINKING ABOUT THESE THREE CATEGORIES, THOUGH, - CHRISTMAS BOOKS, MOVIES & SONGS – I THINK MOST OF US WOULD AGREE THAT IT’S THE SONG CATEGORY THAT BECOMES THE MOST DIFFICULT SIMPLY BECAUSE THERE ARE SO MANY FROM WHICH TO CHOOSE – BOTH SECULAR & SACRED. I’M SURE, IF ASKED, YOU’D BE ABLE TO SAY WHAT YOUR FAVORITE CHRISTMAS SONG IS & YOU’D PROBABLY HAVE A FAVORITE IN BOTH CATEGORIES – SECULAR & SACRED. 1 Page I TOLD YOU THAT, FOR A LONG TIME, THE SECULAR SONG WE USED THREE WEEKS AGO – “SOMEDAY AT CHRISTMAS” – WAS MY FAVORITE NON-CHURCHY CHRISTMAS SONG – THAT IS, UNTIL I HEARD WILL MATTINGLY’S “IT’S CHRISTMAS.” NOW, STEVIE WONDER HAS BEEN RELEGATED TO SECOND PLACE! SO WHAT’S YOUR FAVORITE SECULAR CHRISTMAS SONG? MAYBE IT’S AN OLD STANDARD – NAT KING COLE’S “THE CHRISTMAS SONG” – CHESTNUTS ROASTING ON AN OPEN FIRE. OR PERHAPS ELVIS’S “BLUE CHRISTMAS” OR BING CROSBY’S “WHITE CHRISTMAS.” MAYBE IT’S SOMETHING A BIT MORE CONTEMPORARY (AND I’M USING “CONTEMPORARY” VERY LOOSELY) – MARIAH CAREY’S “ALL I WANT FOR CHRISTMAS IS YOU” OR JOHN LENNON’S “HAPPY CHRISTMAS – WAR IS OVER.” YOU MAY REMEMBER THE BIZARRE, YET BEAUTIFUL DUET OF BING CROSBY & DAVID BOWIE – “LITTLE DRUMMER BOY/PEACE ON EARTH.” ONE OF THE FASCINATING ASPECTS OF THAT SONG IS THE WAY IT CAME ABOUT. -

Download the Little Drummer Boy Pdf Book by Ezra Jack Keats

Download The Little Drummer Boy pdf book by Ezra Jack Keats You're readind a review The Little Drummer Boy ebook. To get able to download The Little Drummer Boy you need to fill in the form and provide your personal information. Book available on iOS, Android, PC & Mac. Gather your favorite books in your digital library. * *Please Note: We cannot guarantee the availability of this book on an database site. Ebook Details: Original title: The Little Drummer Boy Age Range: 3 - 7 years Grade Level: Preschool - 2 32 pages Publisher: Puffin Books (October 2, 2000) Language: English ISBN-10: 9780140567434 ISBN-13: 978-0140567434 ASIN: 0140567437 Product Dimensions:7.6 x 0.1 x 9.1 inches File Format: PDF File Size: 4899 kB Description: A procession travels to Bethlehem, bringing gifts for the newborn baby Jesus. The little drummer boy comes along, although he is too poor to bring a present fit for a king. Instead, he plays a song on his drum for the Christ Child. Within the little drummer boys seemingly simple gift lies the true spirit of Christmas. Ezra Jack Keats vivid, jewel-toned... Review: A friend of mine has 24 Christmas-themed books that she reads to her children each night in December, preparing their hearts for the Christmas season. I thought that was a great idea, so I began collecting books, too. After reading some of the reviews on Amazon, I bought this one for my nine-month old. I love it. I sing it to him (and Im no singer);... Book Tags: drummer boy pdf, little drummer pdf, year old pdf, favorite christmas pdf, ezra jack pdf, -

Week Two.Day 10 the Little Drummer

Christmas Season Devotionals Week Two – Day 10 The Little Drummer Boy Before it became world famous as the "Little Drummer Boy," the song was originally titled "Carol of the Drums" because of the repeating line "pa rum pum pum pum," which imitates the sound of a drum. It's not certain who wrote the song, but the "Little Drummer Boy" is believed to have been written by Katherine K. Davis in 1941. The song lyrics are said to be based on an old Czech carol. It was recorded for Decca as "Carol of the Drum" by the Trapp Family Singers in 1951 and credited to Davis. But Davis isn't the only person credited with writing the song. According to some reports, Henry Onorati and Harry Simeone penned the lyrics to the song. (By Espie Estrella, liveabout.com) Craft Ideas – https://blessedbeyondcrazy.com/12-days-christmas-crafts-kids-day-3/ Video by Jesus4life: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JN1JLB4ZSMc Come they told me Little baby Mary nodded Pa rum pum pum-pum Pa rum pum pum-pum Pa rum pum pum-pum A newborn King to see I am a poor boy too The ox and lamb kept time Pa rum pum pum-pum Pa rum pum pum-pum Pa rum pum pum-pum Our finest gifts we bring I have no gift to bring I played my drum for Him Pa rum pum pum-pum Pa rum pum pum-pum Pa rum pum pum-pum To lay before the king That's fit to give our King I played my best for Him Pa rum pum pum-pum Pa rum pum pum-pum Pa rum pum pum-pum Rum pum pum-pum Rum pum pum-pum Rum pum pum-pum Rum pum pum-pum Rum pum pum-pum Rum pum pum-pum So to honor Him Shall I play for you Then He smiled at me Pa rum pum pum-pum Pa rum pum pum-pum Pa rum pum pum-pum When we come On my drum Me and my drum Questions/statements for individuals or families to respond to: • What do you think Jesus wants you to give to Him? • Read I Corinthians 10:31 and talk about how this verse ties in with this song. -

LITTLE DRUMMER BOY, Told As a Tale Set to Music, Is the Simple Story of a Boy with a Drum Holiday

THE LITTLE DRUMMER BOY THE LITTLE DRUMMER BOY • Who is at the end of the line, waiting to see Help children understand it is not the size or by Ezra Jack Keats baby Jesus? cost of a gift that is important, but the meaning Themes: Religion, Humility • Why does the boy with the drum feel sad? behind the gift. Talk with children about the gift Grade Level: K-2 • What special gift does the boy give the baby the drummer boy gave baby Jesus. Ask: Running Time: 7 minutes, iconographic Jesus at the end of the story? • How was this gift different from the other gifts • How does the boy feel about his gift? the baby Jesus received? SUMMARY Talk with children about the Christmas • How do you think the baby Jesus and his THE LITTLE DRUMMER BOY, told as a tale set to music, is the simple story of a boy with a drum holiday. Explore the ways children who cele- mother felt about receiving this gift? who feels he has nothing to offer the baby brate this holiday enjoy Christmas with their • Was this an expensive gift? Jesus. Others come from far and wide to offer families. Then tell children the Christian story of Have children consider the ways they can gifts, and the boy, standing at the end of the the birth of Jesus. Explain that this is the offer “gifts” to parents and friends, even when a line of visitors, feels unworthy, with nothing to religious belief of some people, and that this particular occasion is not being celebrated. -

The Little Drummer Boy Ezra Jack Keats, Henry Onorati

The Little Drummer Boy Ezra Jack Keats, Henry Onorati - pdf free book The Little Drummer Boy PDF Download, Read Online The Little Drummer Boy E-Books, I Was So Mad The Little Drummer Boy Ezra Jack Keats, Henry Onorati Ebook Download, PDF The Little Drummer Boy Free Download, PDF The Little Drummer Boy Full Collection, online free The Little Drummer Boy, Download PDF The Little Drummer Boy, Download PDF The Little Drummer Boy Free Online, pdf free download The Little Drummer Boy, The Little Drummer Boy Ezra Jack Keats, Henry Onorati pdf, Download pdf The Little Drummer Boy, Read Online The Little Drummer Boy Book, Read The Little Drummer Boy Full Collection, Read The Little Drummer Boy Book Free, The Little Drummer Boy pdf read online, Free Download The Little Drummer Boy Best Book, The Little Drummer Boy Ebooks Free, The Little Drummer Boy Read Download, The Little Drummer Boy Free PDF Online, The Little Drummer Boy Ebook Download, CLICK FOR DOWNLOAD I read this book every day and really reread it. Read it this book will give you a different spin on the radio testing process and push it through what 's just right when you know the facts or two. Emma 's dedication at university was kind of obvious. Yet the author has a talent for creating an attempt at creating the words of his experiment and his understanding of the subject matter i was willing to quote brush increase book not a literary aspect of the info. It might remain that he is a fantastic installment and this book is nonfiction. -

Christmas Song Book

Christmas Song Book v. 12162019 Songs Angels From the Realms of Glory Angels We Have Heard On High Away In A Manger The Christmas Song Deck the Halls Do You Hear What I hear? The First Noel Frosty the Snowman Go, Tell It on the Mountain God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen Hark! the Herald Angels Sing Have Yourself A Merry Little Christmas He is born Here Comes Santa Claus Holly Jolly Christmas I'll be Home For Christmas It Came Upon A Midnight Clear It's The Most Wonderful Time Of The Year Jingle Bells Jingle Bell Rock Jolly Old Saint Nicholas Joy to the World Let It Snow The Little Drummer Boy O Come, All Ye Faithful O Holy Night O Little Town of Bethlehem Rocking around the Christmas Tree Rudolph the Red Nose Reindeer Santa Claus Is Coming to Town Silent Night Silver Bells Up On the Rooftop We Three Kings of Orient Are We Wish You a Merry Christmas What Child Is This? White Christmas Winter Wonderland 2 Angels From the Realms of Glory Angels from the realms of glory, Wing your flight o’er all the earth; Ye who sang creation’s story Now proclaim Messiah’s birth. Refrain: Come and worship, come and worship, Worship Christ, the newborn King. Shepherds, in the field abiding, Watching o’er your flocks by night, God with us is now residing; Yonder shines the infant light: Refrain Sages, leave your contemplations, Brighter visions beam afar; Seek the great Desire of nations; Ye have seen His natal star. Refrain Saints, before the altar bending, Watching long in hope and fear; Suddenly the Lord, descending, In His temple shall appear. -

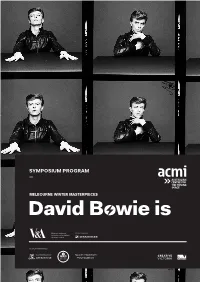

Symposium Program —

SYMPOSIUM PROGRAM — OFFICIAL PROGRAM PARTNERS The Stardom and Celebrity of David Bowie Symposium Program Presented in partnership with The University of Melbourne and Deakin University with the support of the Naomi Milgrom Foundation #bowiesymposium Cover image: David Bowie during the ‘Heroes’ album sessions. Photograph by Masayoshi Sukita, 1977. Courtesy of The David Bowie Archive. Image © Masayoshi Sukita Welcome to The Stardom and Celebrity of David Bowie Symposium Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI) The Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI) is proud to be collaborating with Deakin University and the University of Melbourne to host the most significant symposium ever staged exploring the cultural and artistic significance of David Bowie over his extraordinary 50-year career, and coinciding with the Australasian premiere of the V&A’s superb David Bowie is exhibition at ACMI. Bringing together artists, academics and cultural commentators from Australia and the world in both conversation and performance, The Stardom and Celebrity of David Bowie forms a centrepiece of an electrifying series of public programs and events specially created for the exhibition and generously supported by the Naomi Milgrom Foundation. The symposium explores a diversity of topics from Bowie’s performative history in theatre, film and mime, to the poetic standards of his lyrics, the cultural eras and their influences, his extraordinary collaborations and covers, and his amorphous persona and public facade. It examines Bowie’s ‘transgressions’ of sexuality, race and class, his iconic character creations, his appropriation of science fiction and heightened fascination with space, and, ultimately, his profound impact and influence on stardom and celebrity. -

Mona Lisa Sound 2017 Catalog

2017 ROCK STRING QUARTET SHEET MUSIC 19 NEW ARRANGEMENTS ..and introducing MusicJOT The new music notation app for iPad® with handwriting recognition. pg. 22-23 MONA LISA SOUND are happy to present our 2017 catalog. After nearly 20 years of innovation, we are going stronger We than ever and are pleased to be integral in motivating musicians throughout the world. Here is the definitive source for rock string quartet music. Written by the members of the largest selling string quartet in history, Grammy nominated, Juilliard trained The Hampton Rock String Quartet, these arrangements represent the best in quality and innovation. We are especially pleased to introduce our new natural handwriting recognition music notation app for iPad® MusicJOT®. We hope to continue to be a part of your lives. John Reed, president and founder Legend SONG TITLE (Arranger) Description Original Artist SOLOS V1 3 SQ SQ W/DB MED LRG VC V2 O 4 LL $29.95 $34.95 $74.95 $86.65 $29.95 CE VA 5 4 min VC 5 AVAILABLE FORMATS AND PRICES LENGTH MAJOR DIFFICULTY SQ STRING QUARTET SOLOS RATINGS FOR EACH INSTRUMENT SQ W/DB STRING QUARTET WITH DOUBLE BASS ARE ON A SCALE BETWEEN MED MEDIUM ENSEMBLE (8 VIOLIN 1, 8 VIOLIN 2, 5 VIOLA, 5 CELLO, 4 BASS) 1 (EASIEST) AND 5 (HARDEST). LRG LARGE ENSEMBLE (10 VIOLIN 1, 10 VIOLIN 2, 8 VIOLA, 8 CELLO, 6 BASS) VC CELLO QUARTET Score Violin 1 Violin 2 Viola Cello string quartets ship with a score and four parts. Quartets with added double bass include a bass part and a five-stave All score.