Transcript of Oral History Interview with Robert Clyde Hanson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Groundwork Buddhist Studies Reader

...thus we have heard... (may be reproduced free forever) Buddhist Studies Reader Published by: Groundwork Education www.layinggroundwork.org Compiled & Edited by Jeff Wagner Second Edition, May 2018 This work is comprised of articles and excerpts from numerous sources. Groundwork and the editors do not own the material, claim copyright or rights to this material, unless written by one of the editors. This work is distributed as a compilation of educational materials for the sole use as non-commercial educational material for educators. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. You are free to edit and share this work in non-commercial ways. Any published derivative works must credit the original creator and maintain this same Creative Commons license. Please notify us of any derivative works or edits. "53 Wearing the broad-brimmed hat of the west, symbolic of the forces that guard the Buddhist Studies Reader wilderness, which is the Natural State of the Dharma and the true path of man on Earth: Published by Groundwork Education, compiled & edited by Jeff Wagner all true paths lead through mountains-- The Practice of Mindfulness by Thích Nhất Hạnh ..................................................1 With a halo of smoke and flame behind, the forest fires of the kali-yuga, fires caused by Like a Leaf, We Have Many Stems by Thích Nhất Hạnh ........................................4 the stupidity of those who think things can be gained and lost whereas in truth all is Mindfulness -

Shedding & Gathering

Shedding & Gathering 23 minutes For an audio version in English and Spanish dial: 646-880-9127 To stream, visit www.thebushwickstarr.org/ silverliningradio Fall is the time of shedding old leaves and gathering what we need. Today, we’re going let go of, and how to gather what gives us strength. We’ll share 2 exercises from our audio program that invite this theme. 1. We’re going to warm up by shedding our “leaves.” The things you’re tired of carrying, or that you’re ready to let go of—we’re going to call those “leaves.” Each time we shed a “leaf,” we’ll shake a part of our body like we are helping the wind blow that leaf away. wrists. You can shed leaves from your belly or the top of your head or your nose. Or from anywhere you are holding tension. Let’s name some “leaves” and shed them one by one. Caitlin: So for me, one leaf I want to shed is DESPAIR. And I will shake my arms and wrists like branches in the wind and, while I’m shaking, call out: “DESPAIRRRRRR” Caitlin and Rachel call out “DESPAAIIIRRRR” while shaking their upper bodies. Your turn. You can shed as many leaves as you need to. 2. There are lots of important signs we are seeing in New York City windows these days, ranging from Black Lives Matter posters to thank you notes for essential workers. And there are so many MORE messages we could use—so many things that we still need to be reminded of. -

The Burgess Bird Book for Children Thornton W

The Burgess Bird Book for Children Thornton W. Burgess TO THE CHILDREN AND THE BIRDS OF AMERICA THAT THE BONDS OF LOVE AND FRIENDSHIP BETWEEN THEM MAY BE STRENGTHENED THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED I JENNY WREN ARRIVES. Introducing the House Wren. II THE OLD ORCHARD BULLY. The English or House Sparrow. III JENNY HAS A GOOD WORD FOR SOME SPARROWS. The Song, White-throated and Fox Sparrows. IV CHIPPY, SWEETVOICE AND DOTTY. The Chipping, Vesper and Tree Sparrows. V PETER LEARNS SOMETHING HE HADN'T GUESSED. The Bluebird and the Robin. VI AN OLD FRIEND IN A NEW HOME. The Phoebe and the Least Flycatcher. VII THE WATCHMAN OF THE OLD ORCHARD. The Kingbird and the Great Crested Flycatcher. VIII OLD CLOTHES AND OLD HOUSES. The Wood Peewee and Some Nesting Places. IX LONGBILL AND TEETER. The Woodcock and the Spotted Sandpiper. X REDWING AND YELLOW WING. The Red-winged Blackbird and the Golden-winged Flicker. XI DRUMMERS AND CARPENTERS. The Downy, Hairy and Red-headed Woodpeckers. XII SOME UNLIKE RELATIVES. The Cowbird and the Baltimore Oriole. XIII MORE OF THE BLACKBIRD FAMILY. The Orchard Oriole and the Bobolink. XIV BOB WHITE AND CAROL THE MEADOW LARK. The So-called Quail and the Meadow Lark. XV A SWALLOW AND ONE WHO ISN'T. The Tree Swallow and the Chimney Swift. XVI A ROBBER IN THE OLD ORCHARD. The Purple Martin and the Barn Swallow. XVII MORE ROBBERS. The Crow and the Blue Jay. XVIII SOME HOMES IN THE GREEN FOREST. The Crow, the Oven Bird and the Red-tailed Hawk. -

Pinéda Soraca Wins ASCSU Election Presidency Won by 22 Votes, Diversity Amendment Ratified by Student Body

Thursday, April 7, 2016 Volume 125, No. 43 • collegian.com Pinéda Soraca wins ASCSU election Presidency won by 22 votes, diversity amendment ratified by student body NEWS Ethics award CSU professor wins award for his work with animals PAGE 4 SPORTS Basketball sta Assistant and associate coaches leave CSU for other coaching opportunities PAGE 14 BLOGS Daniela Pinedá Soraca celebrates moments after the announcement of being elected ASCSU President for the 2016-17 school year. PHOTO BY ABBIE PARR COLLEGIAN Late night By Erin Douglas @erinmdouglas23 in the two-campaign election, thing. Included in the write in seats for members of Student Pineda Soracá won the ASCSU votes for president were, “Pro- Diversity Programs and Services study tips 2016-2017 presidency with 1,596 fessor Chaos, Snoop Dog, Willy oces, as well as student organi- Learn what you A narrow win for the Associ- votes from the student body. The Nelson, The On Campus Stadi- zations that represent historical- ated Students of Colorado State Ashley Higgins campaign re- um and The Based God (Lil’ B).” ly under represented groups. can do to stay University president and vice ceived 1,574 votes. The constitution was ratified ASCSU requires at least 10 president went to Daniela Pi- A total of 3,545 students vot- after 12 percent of the student percent of the student body to focused during neda Soracá and running mate ed; 375 students students either body turned out to vote. The ratify the constitution each year. finals season Mike Lensky Wednesday. voted for a write-in candidate constitution -

Paul Mccartney, 1980-1999

Paul McCartney from Wings through the 90's McCartney II Columbia FC‐36511 May 21, 1980 About ten years after recording McCartney by himself, Paul got several songs together and recorded them‐‐again alone‐‐on somewhat of a lark. Then Paul embarked on his ill‐fated 1980 tour of Japan (which resulted in his being jailed for drug possession). After returning to the safety of his own home, he was urged to release the album, and he did. The album contrasts well with McCartney, for this second production contains numerous instruments and electronic tricks that were not present on the 1970 release. Side One is particularly interesting. The solo version of "Coming Up" is followed by the fun track, "Temporary Secretary" (released as a single in England). The almost‐lament, "On the Way," is then succeeded by "Waterfalls," Paul's second (US) single from the album. "Bogey Music," from Side Two, is also a standout. John Lennon heard a song from McCartney II and thought that Paul sounded sad. When the album was released in the US, a bonus one‐sided single ‐‐ the hit version of "Coming Up"‐‐was included with the LP. This hit was enough to propel the album to the #3 position on the charts, during a time when disco was now on the wane. "Waterfalls" Columbia 1‐11335 Jul. 22, 1980 The lovely ballad about protectiveness was one of the standouts from McCartney II. After "Coming Up," it received the most airplay and the most positive response from Paul's friends. As a single, though, the song fared poorly, only reaching #83...one of Paul's worst showings to date. -

Uncle Wiggily in Connecticut

NINE STORIES – J. D. Salinger Uncle Wiggily in Connecticut IT WAS ALMOST THREE O'CLOCK when Mary Jane finally found Eloise's house. She explained to Eloise, who had come out to the driveway to meet her, that everything had been absolutely perfect, that she had remembered the way exactly, until she had turned off the Merrick Parkway. Eloise said, "Merritt Parkway, baby," and reminded Mary Jane that she had found the house twice before, but Mary Jane just wailed something ambiguous, something about her box of Kleenex, and rushed back to her convertible. Eloise turned up the collar of her camel's-hair coat, put her back to the wind, and waited. Mary Jane was back in a minute using a leaf of Kleenex and still looking upset, even fouled. Eloise said cheerfully that the whole damn lunch was burned-- sweetbreads, everything--but Mary Jane said she'd eaten anyway, on the road. As the two walked toward the house, Eloise asked Mary Jane how it happened she had the day off. Mary Jane said she didn't have the whole day off; it was just that Mr. Weyinburg had a hernia and was home in Larchmont, and she had to bring him his mail and take a couple of letters every afternoon. She asked Eloise, "Just exactly what is a hernia, anyway?" Eloise, dropping her cigarette on the soiled snow underfoot, said she didn't actually know but that Mary Jane didn't have to worry much about getting one. Mary Jane said, "Oh," and the two girls entered the house. -

Behind the Songs with Lynn Ahrens and Stephen Flaherty

Behind the Songs with Lynn Ahrens and Stephen Flaherty [00:00:05] Welcome to The Seattle Public Library’s podcasts of author readings and library events. Library podcasts are brought to you by The Seattle Public Library and Foundation. To learn more about our programs and podcasts, visit our web site at w w w dot SPL dot org. To learn how you can help the library foundation support The Seattle Public Library go to foundation dot SPL dot org [00:00:38] Thank you so much. We are so excited over at the Fifth Avenue to be partnering with The Seattle Public Library and these community conversations and we're so thankful that you all decided to come here on this beautiful Monday sunny night in Seattle. I don't know what you're doing inside it's gorgeous out there. Well we're going to wow you with some songs tonight and a wonderful conversation at the Fifth. We're currently presenting "Marie - Dancing Still", a new musical based on the life of and the world of the young ballet student who inspired the masterpiece by Dagmar. The little dancer. And tonight we have two very special guests with us the writers of Lynn Ahrens who wrote the book and lyrics and Stephen Flaherty who composed the music. Ahrens similarity we're gonna embarrass you a little bit. You are considered the foremost theatrical songwriting team of their generation and that's true. They are. They of course wrote the Tony Award winning score for the musical masterpiece ragtime and began their Broadway career with the irresistible. -

Miss Lisa's Preschool Songbook

Miss Lisa’s Preschool Songbook by Lisa Baydush Early Childhood Music Specialist www.Lisa Baydush.com © 2018 Miss Lisa’s Preschool Songbook Themes: Holidays: All About Me… 01 Havdalah & Animals… 02 Rosh Chodesh… 31 Classroom Routines… 03 Shabbat Sings… 32 Colors… 04 Rosh Hashanah… 34 Community… 05 Yom Kippur… 36 Counting… 06 Sukkot… 37 Creation… 07 Simchat Torah… 39 Finger-Plays Thanksgiving… 40 & Chants… 08 Chanukah… 41 Friendship… 09 Tu B’shvat… 44 Giving Thanks… 10 Purim… 46 Hello & Goodbye… 11 Pesach… 48 Just for Fun… 13 Yom Ha-atzmaut… 51 Movement… 15 Movement with Stretchy Bands… 18 Nature/Weather… 19 Noah… 20 Percussion/Rhythm… 21 Planting & Growing… 22 Prayer… 23 Seasons-Fall... 24 Seasons-Winter... 25 Seasons-Spring... 26 Story Songs… 27 Tikkun Olam… 28 Transportation… 30 All About Me Big My Body is Part of Me by Wayne Potash (video) by Ellen Allard (audio) I once was one but now I'm two, This is my head, it is my rosh! (2x) I'm almost as big as you! My rosh is part of my body… and my body is part of me, Chorus: and I’m as happy as can be! B, I, G, I'm big (3x) I'm big, big, big! This is my eye, it is my a-yin… This is my nose, it is my af… I once was two but now I'm three, This is my mouth, it is my peh… I'm as big as I can be! (chorus) This is my hand, it is my yad… This is my leg, it is my regel… I once was three but now I'm four, Look at me I've grown some more! (chorus) Af, Peh, Ozen by Jeff Klepper (audio) Look at Me Af, peh, ozen, ayin, regel, by Lisa Baydush (audio) Af, peh, ozen, yad v’rosh! (repeat) Chorus: Every part of my body Look at me, look at me, has a Hebrew name. -

The Burgess Animal Book for Children

The Burgess Animal Book For Children By Thornton W. Burgess The Burgess Animal Book For Children CHAPTER I Jenny Wren Gives Peter Rabbit an Idea "As sure as you're alive now, Peter Rabbit, some day I will catch you," snarled Reddy Fox, as he poked his black nose in the hole between the roots of the Big Hickory-tree which grows close to the Smiling Pool. "It is lucky for you that you were not one jump farther away from this hole." Peter, safe inside that hole, didn't have a word to say, or, if he did, he didn't have breath enough to say it. It was quite true that if he had been one jump farther from that hole, Reddy Fox would have caught him. As it was, the hairs on Peter's funny white tail actually had tickled Reddy's back as Peter plunged frantically through the root-bound entrance to that hole. It had been the narrowest escape Peter had had for a long, long time. You see, Reddy Fox had surprised Peter nibbling sweet clover on the bank of the Smiling Pond, and it had been a lucky thing for Peter that that hole, dug long ago by Johnny Chuck's grandfather, had been right where it was. Also, it was a lucky thing that old Mr. Chuck had been wise enough to make the entrance between the roots of that tree in such a way that it could not be dug any larger. Reddy Fox was too shrewd to waste any time trying to dig it larger. -

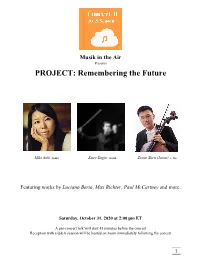

Luciano Berio, Max Richter, Paul Mccartney and More

Musik in the Air Presents PROJECT: Remembering the Future Miki Aoki, piano Emre Engin, violin Zexun Shen (Jason), cello Featuring works by Luciano Berio, Max Richter, Paul McCartney and more. Saturday, October 31, 2020 at 2:00 pm ET A pre-concert talk will start 45 minutes before the concert Reception with a Q&A session will be hosted on zoom immediately following the concert 1 ♫ Program ♫ On the Nature of Daylight Max Richter (1966-0000) Zexun Shen (Jason), cello Miki Aoki, piano Selections from 6 Encores for Piano Luciano Berio (1925-2003) Wasserklavier Erdenklavier Luftklavier Feuerklavier Miki Aoki, piano Two Pieces for String Duo György Ligeti (1923-2006) Ballad and Dance Hommage à Hilding Rosenberg Emre Engin, violin Zexun Shen (Jason), cello A Leaf Paul McCartney (1942-0000) Andante semplice Poco piu mosso Allegro ritmico Andante Allegro ma non tanto Moderato Andante semplice II Miki Aoki, piano Mercy Max Richter (1966-0000) Emre Engin, violin Miki Aoki, piano Sequenza VIII for violin Luciano Berio (1925-2003) Emre Engin, violin 2 ♫ Concert in Brief ♫ This is the kind of program where the audience may wonder about the connection between a classical composer (Luciano Berio), One of the Beatles (Paul McCartney) and one of today’s most successful movie/TV series soundtrack composers (Max Richter). Luciano Berio, an avant-garde European composer (Italian) was born in 1925. It is hard to imagine that he had any connection to a group like the Beatles. It is surprising, but true that both sides had great admiration for each other. Paul McCartney was searching for new ideas for his music. -

Home Visit Notes-Weather Revised.Pdf

Home Visit Notes Lesson: Wise about Weather Objectives: • Encourage reading in the home and model reading skills. • Empower the student with knowledge. • Increase the confidence level of the student in the classroom and as a parent. • Help students see themselves as capable teachers of their children. • Foster fun learning interaction between parent and child. • Reinforce knowledge learned in the classroom by following up in the home. • Provide hands-on activities. • Provide and encourage healthy snacks. Activities: General—All types of weather 1. Weather Kitty—Discuss what types of clothes you would wear on a rainy day, snowy day, hot & sunny day, etc. Dress the Weather Kitty with the appropriate clothes for the day. (You can find additional categories of clothes and cut-out kids at www.makingfriends.com) Use sticky tack to attach the clothes to the Kitty. Sing the Weather song as you do it. (Melody is the Flintstones song.) Weather, What’s the weather. What’s the weather like outside today? (Child’s name) can you tell us if we can go outside and play today? 2. Encourage reading by making a bookmark. Cut a shape out of foam board and glue it to a Popsicle stick. You can use different shapes for different times of the year. For example, a leaf or pumpkin for fall or a snowman for the winter. Write a corresponding phrase on the Popsicle stick before gluing the foam shape. For example, “Fall for Reading”. (A leaf template is included in activity # 21.)The child can also color the Popsicle stick with markers to match or contrast the foam shape. -

Imperial Students Dive Head First Into RAG Week

felixonline.co.uk @felixImperial /FelixImperial [email protected] Keeping the cat free since 1949 issue 1597 February 13th 2015 Union Council votes in favour of Inside... How solar energy is closing Weeks Hall evolving Hall may turn into childcare facilities for staff News, page 6 Science 12-13 Felix previews the Imperial students Cricket World Cup dive head first into RAG Week Sports 46-47 Steven Cowley: physics, fusion and hair Felix covers the Features 10-11 Council votes to reduce charity events that rent of Acton halls have taken over campus News, pages 4 and 5 News 7 2 13.02.2015 THE STUDENT PAPER OF IMPERIAL COLLEGE LONDON FELIX This week’s issue... [email protected] Felix Editor Philippa Skett CONTENTS EDITORIAL TEAM Editor-In-Chief I’m too tired to think PHILIPPA SKETT News 3–8 Deputy Editor PHILIP KENT Features 10–11 Treasurer Science 12-14 of a decent title here THOMAS LIM Technical Hero Games 15 LUKE GRANGER-BROWN his week Union Council made Fun Felix Fact: I sit on Council and Music 16–17 a lot of decisions that could get a vote as the PG Non Faculty News Editors potentially affect students in Representative, not as Felix editor, CAROL ANN CHEAH T KUNAL WAGLE Television 18 years to come. We passed a paper meaning I represent part of the condemning the Counter Terrorism Business School. Its odd how these Comment Editor Film 29 Bill, another outlining our intentions things work out. TESSA DAVEY to lobby College to divest from fossil Debra Humphris, who was present Welfare 20 fuels, another stating our plans at the Union Council meeting on Technology Editors JAMIE DUTTON to save Pembridge Hall and yet Tuesday, told the students there that OSAMA AWARA Arts 27–34 another about the rent prices for College would listen to the decisions accommodation.