DEPARTMENT of FISH and WILDLIFE Mailing Address: P.O

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flood Profiles and Inundated Areas Along the Skokomish River Washington

(200) WRi iiuiiWiii il no. 73 - 6.2 3 1818 00029385 0 • - .., t-fr 7 [.1a ft 7. 974 -----) ) ----__L___----- FLOOD PROFILES AND INUNDATED AREAS ALONG THE SKOKOMISH RIVER WASHINGTON U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations 62-73 Prepared in Cooperation With State of Washington Department of Ecology BIBLIOGRAPHIC DATA 1. Report No. 2. 3. Recipient's Accession No. SHEET 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Flood Profiles and Inundated Areas Along the Skokomish December 1973 River, Washington 6. 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Rept. J.E. Cummans No. WRI-62-73 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Project/Task/Work Unit No. U.S. Geological Survey, WRD Washington District 11. Contract/Grant No. 1305 Tacoma Avenue So. Tacoma, Washington 98402 12. Sponsoring Organization Name and Address 13. Type of Report & Period U.S.Geological Survey, WRD Covered Washington District Final 1305 Tacoma Avenue So. 14. Tacoma, Washington 98402 15. Supplementary Notes Prepared in cooperation with the Washington State Department of Ecology 16. Abstracts The Skokomish River will contain flows only as large as 4,650 cubic feet per second downstream from U.S. Highway 101, and the flood plain in this reach is subject to inundation on an average of about 10 days each year. From the highway upstream to the junction of the North and South Forks Skokomish River the river will contain flows as large as 8,900 cubic feet per second; such flows occur nearly every year and have occurred at least six times during one flood season. Storage and diversion at Cushman Dam No. -

Skokomish River Basin

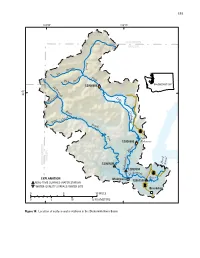

131 124°30’124°30’ 124°15’124°15’ JEFFERSONJEFFERSON MASON No No r r t t h eeaam h SSttrr SSiixx mm Fo aa orr ree kk Fiivvee SSttr 1205650012056500 WASHINGTON SSkoko kk oo 47°47° mm 30'30' iishsh eekk Lake rree Lake C Ruullee Rii CC vveer uu r s ,, s h h m eeekk m e an e rr an iinne C PP SSoutout hh SRSR 119119 FFo o rkrk Lake 1205880012058800 Kokanee eerr iivv RR hh s s MASON MASON i i m m HoodHood CanalCanal GRAYS HARBOR o GRAYS HARBOR 1206050012060500 o kk oo k k S S 1205950012059500 SRSR kkoomiiss 106106 SSkkoo hh r EXPLANATION Mohrweis Riivveer Mohrweis 1206150012061500 REAL-TIME SURFACE-WATER STATION USUS WATER-QUALITY SURFACE-WATER SITE 101101 Brockdale 0055 10 10 MILES MILES 0055 10 10 15 15 KILOMETERS KILOMETERS Figure 18. Location of surface-water stations in the Skokomish River Basin. 132 EXPLANATION Real-time surface-water station Water-quality surface-water station 12056500 12056500 Station number RM 29.2 RM 17.3 River mile Stream—Arrow shows direction of flow Tunnel or pipe—Arrow shows direction of flow Lake Cushman Storage began 1925 RM 19.6 Cushman Dam Powerhouse No. 1 Cushman Dam Skokomish River McTaggert Creek Deer Powerhouse No. 2 Meadow To Hood Creek Lake Kokanee Canal Storage RM began 1930 19.1 RM 17.3 12058800 RM 16.5 McTaggert Creek North Fork RM 13.3 12059500 RM 10.1 South Fork Skokomish River SKOKOMISH RIVER 12060500 RM 12061500 RM 3.29.0 RM 5.3 HOOD CANAL Figure 19. -

Independent Populations of Chinook Salmon in Puget Sound

NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-NWFSC-78 Independent Populations of Chinook Salmon in Puget Sound July 2006 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Marine Fisheries Service NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS Series The Northwest Fisheries Science Center of the National Marine Fisheries Service, NOAA, uses the NOAA Techni- cal Memorandum NMFS series to issue informal scientific and technical publications when complete formal review and editorial processing are not appropriate or feasible due to time constraints. Documents published in this series may be referenced in the scientific and technical literature. The NMFS-NWFSC Technical Memorandum series of the Northwest Fisheries Science Center continues the NMFS- F/NWC series established in 1970 by the Northwest & Alaska Fisheries Science Center, which has since been split into the Northwest Fisheries Science Center and the Alaska Fisheries Science Center. The NMFS-AFSC Techni- cal Memorandum series is now being used by the Alaska Fisheries Science Center. Reference throughout this document to trade names does not imply endorsement by the National Marine Fisheries Service, NOAA. This document should be cited as follows: Ruckelshaus, M.H., K.P. Currens, W.H. Graeber, R.R. Fuerstenberg, K. Rawson, N.J. Sands, and J.B. Scott. 2006. Independent populations of Chinook salmon in Puget Sound. U.S. Dept. Commer., NOAA Tech. Memo. NMFS-NWFSC-78, 125 p. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-NWFSC-78 Independent Populations of Chinook Salmon in Puget Sound Mary H. Ruckelshaus, -

Recreation • NORTH Knowledge Our of Best the to Accurate Is Herein Presented Information All

December 2008 December not responsible for any inaccuracies of map or hardship/injury due to same. same. to due hardship/injury or map of inaccuracies any for responsible not please check for current conditions before planning your trip. Map authors authors Map trip. your planning before conditions current for check please and sources as of printing date. Road conditions change periodically, so so periodically, change conditions Road date. printing of as sources and Mason County Recreation • NORTH knowledge our of best the to accurate is herein presented information All Mason County is home to a variety of outdoor recreation, thanks to our towering mountains, huge tracts of national forest, and hundreds Mason County Transit is Bicycle Friendly! of miles of salt and freshwater shoreline. A variety of bicycle routes are LEGEND highlighted with convenient map keys. Additionally, we’ve identified If roads get too busy or you grow too tired, remember that all Mason simply a matter of judgement regarding safety and passenger loads. BIKEWAYS many scenic and popular launches for kayaking, boating and fishing. For POINTS OF INTEREST County Transit buses provide bike racks. Rarely, but sometimes, you may be asked to take the next bus. If you bring your bicycle on board, please be responsible for its handling those who want to escape further into the forest, this map will show you Bike Routes Convenient, secure and easy-to-use, bicycle racks become a bicyclist’s and security in the wheelchair securement area throughout the trip. some of our favorite trails and trailheads for hiking and exploring. State Public Restroom Visitor Information Heavy Trac ? best friend when weather conditions worsen or visibility lessens due and county parks for camping or outdoor play, Mason Transit bicycle- Schedule Information • 360-426-5033 Boat Launch to darkness, mist or fog. -

Duckabush and Dosewallips Comprehensive Flood Hazard Management Plan

Duckabush and Dosewallips Comprehensive Flood Hazard Management Plan Jefferson County, Washington June 2009 Prepared by: Jefferson County Department of Community Development 621 Sheridan Street Port Townsend, WA 98368 360.379.4450 www.co.jefferson.wa.us and 626 Columbia Street NW Suite 2A Olympia, WA 98501-9000 360.570.4400 This page is intentionally left blank. Duckabush and Dosewallips Comprehensive Flood Hazard Management Plan June 2009 i Table of Contents Section 1 Plan Development............................................................................ 1 1.1 Purpose and Scope ....................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Plan Development Process ........................................................................................... 1 1.3 Advisory Committee Meetings ....................................................................................... 2 1.4 Public Involvement......................................................................................................... 3 1.5 Flood Hazard Management Goals and Objectives........................................................ 3 Section 2 Existing Conditions Analysis ............................................................ 5 2.1 Watershed Description .................................................................................................. 5 2.1.1 CFHMP Planning Area ..................................................................................... 6 2.1.2 Duckabush River ............................................................................................. -

Lower Skokomish Vegetation Management Environmental

Lower Skokomish Vegetation Management United States Department of Agriculture Environmental Assessment Forest Hood Canal Ranger District, Olympic National Forest Service Mason County, Washington June 2016 USDA Non-Discrimination Policy Statement DR 4300.003 USDA Equal Opportunity Public Notification Policy (June 2, 2015) In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication fo r program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. -

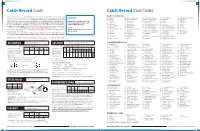

Catch Record Cards & Codes

Catch Record Cards Catch Record Card Codes The Catch Record Card is an important management tool for estimating the recreational catch of PUGET SOUND REGION sturgeon, steelhead, salmon, halibut, and Puget Sound Dungeness crab. A catch record card must be REMINDER! 824 Baker River 724 Dakota Creek (Whatcom Co.) 770 McAllister Creek (Thurston Co.) 814 Salt Creek (Clallam Co.) 874 Stillaguamish River, South Fork in your possession to fish for these species. Washington Administrative Code (WAC 220-56-175, WAC 825 Baker Lake 726 Deep Creek (Clallam Co.) 778 Minter Creek (Pierce/Kitsap Co.) 816 Samish River 832 Suiattle River 220-69-236) requires all kept sturgeon, steelhead, salmon, halibut, and Puget Sound Dungeness Return your Catch Record Cards 784 Berry Creek 728 Deschutes River 782 Morse Creek (Clallam Co.) 828 Sauk River 854 Sultan River crab to be recorded on your Catch Record Card, and requires all anglers to return their fish Catch by the date printed on the card 812 Big Quilcene River 732 Dewatto River 786 Nisqually River 818 Sekiu River 878 Tahuya River Record Card by April 30, or for Dungeness crab by the date indicated on the card, even if nothing “With or Without Catch” 748 Big Soos Creek 734 Dosewallips River 794 Nooksack River (below North Fork) 830 Skagit River 856 Tokul Creek is caught or you did not fish. Please use the instruction sheet issued with your card. Please return 708 Burley Creek (Kitsap Co.) 736 Duckabush River 790 Nooksack River, North Fork 834 Skokomish River (Mason Co.) 858 Tolt River Catch Record Cards to: WDFW CRC Unit, PO Box 43142, Olympia WA 98504-3142. -

Upper South Fork Skokomish River

FY 2011 Watershed Restoration Action Plan Hood Canal Ranger District, Olympic National Forest USDA Forest Service Watershed Condition Framework FY2012 TRANSITION WATERSHED RESTORATION ACTION PLAN Pacific Northwest Region Olympic National Forest, Hood Canal Ranger District Upper South Fork Skokomish River 1 FY 2011 Watershed Restoration Action Plan Hood Canal Ranger District, Olympic National Forest 1. Summary a. Watershed Name and HUC: Upper South Fork Skokomish River, 171100170101 b. General Location: The Upper South Fork Skokomish watershed is located in the southeast corner of the Olympic Peninsula, approximately 25 miles northwest of Shelton, Washington. The majority of the watershed lies within the Hood Canal Ranger District, on the Olympic National Forest. c. Total Watershed Area: 38,538 acres NFS area within watershed: 95% (36,762 acres) d. Watershed Characterization: General Physiography: The watershed is characterized as a steep mountainous terrain, highly dissected by a riverine system, and covered predominantly by a mixed age coniferous forest. Dominant landforms in headwaters have formed a topography that ranges from near vertical basalt hills and dissected incised valley side slopes. Landforms in the lower portion of the watershed once occupied by continental glaciers, have relatively thick deposits of till and outwash forming smooth mountain side slopes and ridges. The mainstem channel occupies the relatively broad, low gradient portion of the main glacial valley. This watershed covers the upper area of the South Fork Skokomish River. The Upper and Lower South Fork Skokomish 6th field watersheds combine to form the South Fork Skokomish. The South Fork and North Fork are the two major tributaries to the Skokomish River. -

2015 Olympic Knotweed Working Group

Combined crews from the Quileute Tribe Natural Resources, Exotic Plant Management Team- Olympic National Park, and Clallam County Noxious Weed Control Board join forces to tackle knotweed in the Twilight Zone of the Quillayute River 2015 Olympic Knotweed Working Group Report Prepared by Clallam County Noxious Weed Control Board Report prepared by Clallam County Noxious Weed Control Board December 2015 223 East 4th Street Ste 15 Port Angeles WA 98362 360-417-2442 [email protected] http://www.clallam.net/weed/projects.html CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................... 1 PROJECT DESCRIPTION ................................................................................... 7 Project Goal ........................................................................................................................ 7 Project Overview ................................................................................................................. 7 2015 Overview .................................................................................................................... 7 2015 PROJECT ACTIVITIES .............................................................................................. 9 2015 PROJECT PROCEDURES .......................................................................................12 OBSERVATIONS AND CONCLUSIONS ...........................................................................15 RECOMMENDATIONS ......................................................................................................16 -

Manganese Deposits of the Olympic Peninsula,· Washington

State of Washington MON C. WALLGREN, Governor Department of Conservation and Development ART GARTON, Director DIVISION OF MINES AND MINING SHELDON L. GLOVER, Supervisor Report of Investigations . No. 7 Manganese Deposits of the Olympic Peninsula,· Washington By STEPHEN H. GREEN Olympia State Printing Plant 1945 For sale by Department of Conservation and Development, Olympia, Washington. Price, 25 cents. CONTENTS Page Foreword............................................................ 3 Introduction . 5 Fieldwork and acknowledgments. 6 Selected bibliography . 7 General production and uses of manganese. 8 Principal economic manganese minerals ............ ................. .. 10 Geology ............................................................. 11 Mineralogy . 15 Bementite . 16 Hausmannite . 17 Neotocite .................................................... 17 Inesite ...................................................... 17 Rhodochrosite .................................... : . 17 Rhodonite . 18 Minor manganese minerals. 18 Weathering products .......................................... 18 Associated minerals ....... ...... : . 18 Origin of deposits. 19 Beneficiation . 20 U.S. Government purchasing scheduLe, 1942 ............................. 24 Estimation of tonnage. 25 Distribution of known occurrences .......... : . 25 Clallam County .................................. ... ............ , 26 Pacific Coast to Lake Crescent vicinity. 26 Aw·ora Ridge area ....................................... ·..... 32 Storm King Mountain area. 33 Little -

Pet-Friendly Destinations

Orcas Island Friday Harbor San Juan Lopez Vancouver Island Anacortes BC Island Island British Columbia THE OLYMPIC Tatoosh Victoria, B.C. 20 Island Neah Bay PENINSULA IS Cape Rd Vancouver, To Hobuck Beach MAKAH RESERVATION 112 Whidbey 5 DOG FRIENDLY! Shi Shi Sekiu Island Beach Clallam Bay 20 OLYMPICPENINSULA.ORG/ Ozette Rd OZETTE Strait of Juan de Fuca DOG-FRIENDLY RESERVATION Hoko- Salt Creek Dungeness Coupeville Spit 112 Loop LOWER ELWHA Port Joyce RESERVATION Port Dungeness Camano Sand Loop Townsend 113 Joyce Angeles Island Point Lake Piedmont East Ozette Beach 112 Hurricane Sequim 101 Gardiner Fairchild Port Lake Intl. Airport 101 Sol Duc Hot Sutherland 19 Hadlock Olympic Springs Rd Ridge Rd B Blyn e a National Forest Sol Duc River v Oak Bay Rd 525 Discovery e Clinton Sol Duc River 20 r JAMESTOWN Quillayute Rd Bay V 110 Sol Duc S’KLALLAM TRIBE a Mora Rd Forks l Port l e WITHIN OLYMPIC Hot Springs y Hurricane Ridge Rialto Beach R Ludlow d NATIONAL PARK La Push Rd Port Mukilteo La Push Bogachiel River Olympic Ludlow Rd Second Beach River Elwha QUILEUTE Hoh Rain Forest 101 Port Dungeness River Dungeness 104 RESERVATION National Forest Hoh River Center Rd Gamble Upper Hoh Rd Quilcene Edmonds Olympic National Park 104 101 Big Quilcene River 3 HOH Hood Canal Kingston Dosewallips Rd RESERVATION Olympic Poulsbo Dosewallips River Ruby Beach National Forest Queets River Brinnon 305 Pacific Duckabush River Bainbridge Clearwater River Silverdale Ocean Kalaloch Island OLYMPIC NATIONAL FOREST Hamma Hamma Rd SEATTLE All trails within the Olympic Hamma Hamma R. Quinault River Bremerton Lake Kitsap National forest are dog-friendly. -

Skokomish Tribe

2016 State of Our Watersheds Report Skokomish-Dosewallips Basin he Skokomish Tribe is wholly devoted to restoring the TSkokomish watershed and its resources – not just for the next five years, not just for another 40 years, but forever. We must continue healing the environment that we depend upon for survival. The health and well-being of the Skokomish watershed is vital to the Skokomish tribal culture, tradition, subsistence and economy. – JOSEPH PAVEL SKOKOMISH TRIBE Skokomish Tribe The Twana (ancestors of the Skokomish people) were the first human inhabitants of the south Hood Canal region, with villages and fishing camps located near streams where they could take advantage of plen- tiful fish and shellfish resources. At the signing of the Point No Point Treaty of 1855, the Skokomish Tribe ceded their traditional lands to the U.S. government, and Washington’s Gov. Isaac I. Stevens assured the Tribe that they could continue Seattle to gather food at the accustomed locations. However, during this period, Euro-Americans began farming the floodplains, cutting the forests, and shellfish and fish resources began to be harvested by settlers. Today, the region is largely rural and forested, communities still rely on logging, fishing, shellfish and recreation. Unfortunately, there have been major land-use impacts on Treaty-protected resources includ- ing salmon habitat. Dam construction, floodplain and shoreline development, and roads and logging have had their impacts. Skokomish Tribe 221 The Hood Canal Watershed: Home of the Skokomish Tribe Hood Canal is a natural, glacier-carved fjord separating the Olympic and Kitsap peninsulas. It stretches 68 miles from the northern tip of the Kitsap peninsula to Lynch Cove, forming an L-shape that remains narrow, ranging from 1.5 to 2 miles across.