In the Cards: a Collection of Short Stories and Poetry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907)

Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907) BuYun Chen Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 BuYun Chen All rights reserved ABSTRACT Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907) BuYun Chen During the Tang dynasty, an increased capacity for change created a new value system predicated on the accumulation of wealth and the obsolescence of things that is best understood as fashion. Increased wealth among Tang elites was paralleled by a greater investment in clothes, which imbued clothes with new meaning. Intellectuals, who viewed heightened commercial activity and social mobility as symptomatic of an unstable society, found such profound changes in the vestimentary landscape unsettling. For them, a range of troubling developments, including crisis in the central government, deep suspicion of the newly empowered military and professional class, and anxiety about waste and obsolescence were all subsumed under the trope of fashionable dressing. The clamor of these intellectuals about the widespread desire to be “current” reveals the significant space fashion inhabited in the empire – a space that was repeatedly gendered female. This dissertation considers fashion as a system of social practices that is governed by material relations – a system that is also embroiled in the politics of the gendered self and the body. I demonstrate that this notion of fashion is the best way to understand the process through which competition for status and self-identification among elites gradually broke away from the imperial court and its system of official ranks. -

24 20 Warns of New Sanction If 'Not Tackled Head-On'

SEND MONEY USING THE BFC APP AND WIN WEEKLY PRIZES ! MOIC/PC/6680/2018 Monday, March 5, 2018 Issue No. 7676 200 Fils Tel: 1722 8888 www.newsofbahrain.com www.facebook.com/nobonline newsofbahrain 38444680 nob_bh www.bfc.com.bh JO3968_BFC_SM_APP_Online_Campaign_DT_Hamper_6.7cmX8.5cm.indd 1 3/1/18 3:45 PM BTI Career Expo Manama career expo will open on the 13th of March at the BahrainA Training Institute (BTI) in Isa Town. The three- day event will be held under the patronage of Education Minister Dr. Majid bin Ali Al-Nuaimi Market revamp Manama His Majesty King Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa yesterday hailed the persistent efforts of Interior Ministry and security agencies in bringing down terror- irector-General of the ists targeting the security and stability of the Kingdom. During a reception held for HRH Prime Minister Prince Khalifa bin Salman Al Khalifa at Sakhir DCapital Trustees’ Board, Palace, HM the King stressed Bahrain will “steadily progress towards development and prosperity” with determination. HM, the King also called on Mohammed bin Ahmed Al Bahrainis to act in concert to continue supporting the economic and development achievements, pointing out the national achievements made in Khalifa said that a number of various fields. development projects will be implemented in the Manama Central Market in 2018. 72 candidates announced for BCCI elections Gender parity in the United Nations Senior Management Group is just Iranian missiles the beginning. Our goal – and my commitment - is to achieve gender parity at all levels. a major concern, @antonioguterres Today’s Weather Max Min 26°C 17°C says France Paris/Manama thousand kilometres, which are programme without the P rance’s foreign minister not compatible with UN Security West’s destruction of its own 03 P Fyesterday issued a stark Council resolutions and which nuclear weapons and long- warning to Iran to control its exceed the needs of defending range missiles. -

Shrek Jr Costume Inventory (For Ages 9-12)

www.performingacademyrentals.com Shrek Jr Costume Inventory (for ages 9-12) Main Set Character Number of Costumes Price Per Look Price Total Individual Pieces in Set Shrek 1 $35 $35 fat suit, cream peasant shirt, brown vest, plaid pants, padded cowl w/ears 1 $5 $5 knight helmet Fiona 2 $30 $60 green long sleeve leotard, green dress or green skirt & vest, tiara 1 $35 $35 wedding dress, petticoat, veil w/crown, headband w/ears, green gloves, nose Donkey 1 $30 $30 full body suit, headband w/ears, hooves Farquad (on knees, must be adult black magnet pants, legs, red long sleeve shirt, red tunic, white tunic, gold cape, gold size) 1 $75 $75 belt, gold gloves, gold gauntlet, crown Farquad (not on knees) 1 $35 $35 black pants, red & gold tunic w/cape, gold gloves, gold gauntlets, crown striped shirt, blue lederhosen, wood body stocking, straw hat, yellow bow tie, white Pinocchio 1 $45 $45 gloves, extendable nose Gingy 1 $25 $25 brown body suit, foam headpiece Peter Pan 1 $30 $30 leaf vest, leaf shorts, shirt w/leaves, hat, belt, wristlets, tights, boot spats purple dress w/cape, black petticoat, black lace fingerless gloves, green choker, green Wicked Witch 1 $30 $30 upper arm bands, purple scrunchie, purple & green witch hat yellow & white checkered shirt, overalls, straw hat w/ears, orange bandana, nose, Straw Pig 1 $30 $30 hooves Sticks Pig 1 $30 $30 brown plaid shirt, khaki pants, stiped newsboy cap w/ears, nose, hooves white dress shirt, maroon velvet pants, maroon suit coat, orange bow tie, little top hat Bricks Pig 1 $30 $30 w/ears, nose, -

Wool 11 Merchandising Planogram 14 Imagery 16 Betmar® Details 16 Sales Agents 17

cover Fall/Winter 2016 112046_BetmarAW16.indd 1 12/29/15 9:19 PM Made in USA 1 Felt 2 Cut and Sew 5 Braid 9 Wool 11 Merchandising Planogram 14 Imagery 16 Betmar® Details 16 Sales Agents 17 Proud Member of American Made Matters® Promoting American craftsmanship and ingenuity. This product complies with American Made Matters® standards for Made in America. Betmar® and LiteFelt® are registered trademarks of the Bollman Hat Company. All Hat Sizes except Made in USA are 1SFM 112046_BetmarAW16.indd 2 12/29/15 9:19 PM Made in USA Made in USA USA Sizes Only: S/M, M/L Blush pictured Burgundy pictured B1675H Mary • Round crown felt cloche B1671H Tessa • Floppy wide brim fedora • Satin trim with Betmar 3/4 • Faux snakeskin band and Brim: 2” metal slider Brim: Front 3 ” buckle Black, Scarlet, Blush* • Made in USA Back 3” • Made in USA • LiteFelt® finish Black, Burgundy* • LiteFelt® finish Navy pictured Olive pictured B1524H Izette II • Floppy brim fedora with B1677H Hannah • Floppy wide brim round 3/4 center dent crown crown Brim: 2 ” • Velvet ribbon trim Brim: 3” • Self trim with hardware Black, Navy*, Cranberry • Made in USA Black, Olive*, Lt. Camel • Made in USA • LiteFelt® finish • LiteFelt® finish Cranberry pictured Navy pictured B1676H Evelyn • Round crown felt cloche B1674H Colleen • Floppy short brim fedora 1/2 • Single pleat detail on brim 1/4 • Grossgrain ribbon trim Brim: 2 ” • Leather cord trim Brim: 2 ” • Made in USA Black, Cranberry*, Lt. Camel • Made in USA Navy*, Chestnut Roast • LiteFelt® finish • LiteFelt® finish Black Navy Olive Burgundy Chestnut Roast Cranberry Scarlet Blush Lt. -

Open Water: a Collection

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2010 Open Water: A Collection Emily Newhook College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Fiction Commons Recommended Citation Newhook, Emily, "Open Water: A Collection" (2010). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 730. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/730 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Open Water: A Collection A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelors of Arts / Science in English from The College of William and Mary by Emily Breton Newhook Accepted for ___________________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) _Ava Coibion____________________________ Director _Anita Angelone__________________________ _Joanne Braxton___________________________ _Hermine Pinson__________________________ Williamsburg, VA April 22, 2010 MAJOR CHARACTERS Miri Wheelan, 63. Married to Jack Wheelan, mother of Eli, Richie, Malcolm and Amy Jack Wheelan, 63 Lester Boyle, 60. Unmarried brother of Miri Eli Wheelan, deceased. Fraternal twin of Richie and the oldest child. Richie Wheelan, 37. Married to Hannah, father of Olive and Anna Malcolm Wheelan, 36. Jack and Miri‟s second youngest. Unmarried. Amy Wheelan, 33. Jack and Miri‟s youngest child and only daughter Olive Wheelan, 14. Richie and Hannah‟s oldest daughter. 2 ONE Richie and I were born three minutes apart in 1960, the same year the Lockheed- Electra crashed into Winthrop Bay. -

Draw Overlapping Cubes with Light on One Side 48

1. Draw overlapping Cubes with light on one side 48. Your favorite game 2. Draw a scrap of a treasure map 49. Your favorite internet meme 3. Draw your day as a comic strip 50. Something that you can't live without 4. Draw a city on another planet 51. A city skyline 5. Draw something you miss 52. Close your eyes, and draw Batman 6. Draw yourself as a Robot 53. A real or made up dinosaur 7. Draw how you feel right now 54. Create a super villain 8. Draw your favorite flower 55. A man eating plant 9. Close your eyes and draw a self-portrait 56. A hover vehicle 10. Redesign the letters in your name to create a logo 57. A Tank 11. Draw a light object in a dark environment 58. A robot army 12. Draw a dark object in a light environment 59. Your shoe 13. Draw something that you need to make art 60. Draw a bottle, jar or tin from the art room 14. Draw a teapot 61. Draw your watch or other piece of jewelry 15. Draw an insect with wings 62. Draw your hand with your non-dominant hand 16. Draw an apple 63. A tool from the art room 17. Draw a brown paper bag 64. Draw a musical instrument 18. Draw a spoon, and color it. Write a short note about 65. The antique saxophone in the art room the last thing you ate with a spoon. 66. Draw something old/vintage/antique in the art room 19. -

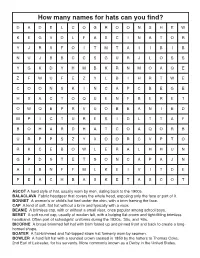

How Many Names for Hats Can You Find?

How many names for hats can you find? D A D E L C O G R O O N S H E W K E G V D L F A S C I N A T O R Y J R S F O I T M T A I I B I B N U J B B C C S G U R J L O S S Y G K D Y H M B K R N M O A Q E Z F W U F E Z Y L B I H R T W E C O O N S K I N C A P C B E G E H X A C T O Q U E N F B E R E T O W Q E P R V U O B E A N I E D M P I C T U R E S I D L T T A F B O H A R D H A T C O A Q O R B U R P P S Z Y X O O R C V P T O R K C E B O W L E R A L H H U N G P D S T E T S O N C A P A J N A I B N F F M L K E I V I T D E P E A C H B A S K E T A S C O T ASCOT A hard style of hat, usually worn by men, dating back to the 1900s. -

Felixonline.Co.Uk

The student ‘news’paper of Imperial College London Guardian Student Newspaper of the Year 2006, 2008 Issue 1,417 Friday 28 November 2008 felixonline.co.uk felix Inside Page 3 - It’s coming!! Centre Page Clubs and Socs - Panto time! Page 30 Technology - Affordable Gadgets Page 29 Varsity Build Up - The Medics’ point of view Yes we did! Who is that to the right of Tomo? I thought he didn’t like his photo being taken. Read the full story on pages 2 and 3 Page 37 2 felix Friday 28 November 2008 Friday 28 November 2008 felix 3 News [email protected] News News Editor – Kadhim Shubber [email protected] felix scoops top Being the best of the best Daniel Wan interviews this year’s Guardian Journalist of the prize at student Year and editor in chief of last year’s felix Tom Roberts media awards t’s the morning after last night’s I had ambitions from the beginning Another Castle is the new gam- Jovan Nedić row and the title was passed on to cher- Guardian Student Media of how I wanted the paper to look, and ing magazine. Gaming is one of my Editor in Chief well.org, University of Oxford. Awards ceremony, and trium- I think I achieved that, but I don’t think main hobbies. I’m a massive geek who Once the winners had left the stage, phant ex-Editor Tom Roberts you would ever believe that you could likes playing computer games all day! This year’s Guardian Student Media it was then time to find out who would comes down to the felix office to win the awards. -

Autumn/Winter 2020 LUXE COLLECTION Sizes: S/M, M/L

Autumn/Winter 2020 LUXE COLLECTION Sizes: S/M, M/L Luxe Collection 2 Felt 5 Rain 9 Cut and Sew 11 Braid 13 Knit 15 • Pinch crown fedora B1956H Michele* B1968H Joelle* • Round crown & 1/2 • Partial band trim All hat sizes except Luxe Collection are 1SFM Brim: 2 ” Brim: Front 2 3/4”, Back 2 1/4” asymmetrical felt cloche • Felt twist bow applique • Cut petal opening Black, Italian Plum*, • Polished felt finish Black*, Redwood Redwood, Truffle • Tiny velvet ribbon flower • Adjustable sweatband trim • Made in the USA • Adjustable sweatband USA Customer Service & Distribution Center • Made in the USA 110 E. Main Street, Adamstown, PA 19501 T: 800-859-4653 F: 888-428-7329 Betmar New York Showroom 411 Fifth Avenue, 2nd Floor, New York, NY 10016 T: 212-981-9900 Europe Customer Service T: +44(0)1946 810 312 F: +44(0)1946 811 087 B1677H Hannah* • Round crown floppy B1883H Ashland* • Medium brim fedora with • Self trim with hardware pinched crown Brim: 3 1/2” Brim: 2 1/2” • Polished felt finish • Grosgrain ribbon band & Betmar® Details Black, Dark Plum, • Adjustable sweatband Black, Olive*, Slate tassels trim Light Camel*, Olive • Made in the USA • Adjustable sweatband • Polished felt finish • Made in the USA Antique Brass Pin Antique Brass Slider Gunmetal Pin Polished Gunmetal Slider Sweatband Black Burgundy Dark Plum Italian Plum Adjustable Sweatband Ribbon Loop B1671H Tessa* • Floppy wide brim fedora • Faux snakeskin band & Brim: Front 3 1/4”, Back 3” buckle Light Camel Olive Redwood Slate PROUD SPONSOR OF AMERICAN MADE MATTERS Black*, Burgundy -

In This Month's Hatalk

Issue 56, November 2010 Next issue due 17 November 2010 HATalk the e-magazine for those who make hats In this month’s HATalk... Millinery in Practice People at work in the world of hats. This month: Alison Bailey Smith - working with recycled materials. Hat of the Month A delightful sinamay hat by Sheila Shannon. Focus on... The inaugural Bridport Hat Festival; N and O in the A to Z of Hats. How to… Use crochet, trim hats with zippers and try alternative hat bands. Plus – Letters to the Editor, this month’s Give Away and The Back Page. Published by how2hats.com click here to turn over i Issue 56 Contents: November 2010 Millinery in Practice People at work in the world of hats. This month: A look at the work of Alison Bailey Smith, milliner extraordinaire and recycling queen. Hat of the Month Learn about this lovely hat and something about Sheila Shannon, its creator. Focus on... The Bridport Hat Festival and competition - the first event of its kind in the UK. The A to Z of Hats Needle, Newsboy, Optimo and more - learn hat words that start with N and O. How to... Use millinery crochet to add texture to your hats. Something new to try... Make a multi-coloured zip and use it as a hat decoration. Another Way... Two more alternatives to the classic petersham hat band. This Month’s Give Away We’re giving you the chance to win an old How2hats classic in a new form. Letters to the Editor This month: When can you call yourself a milliner? The Back Page Interesting hat facts; books; contact us and take part! 1 previous page next page Alison Bailey Smith Recycling Technology Alison Bailey Smith, the self-proclaimed Techno Cannibal, has been making hats for over 20 years. -

Fall/Winter 2020 Catalog

Fall & Winter 2020 4 Collections 13 b 16 3 r 17 r 3Tu Originalbans 3-Seam (Yearround Selection) 18Outdoo Miami Visor Hats 4 Original 3-Seam (Seasonal Selection) 19 Sydney Jersey Hat Organic 3-Seam 20 Jordan Newsboy Cap 5 Soft Heather 3-Seam Denim Topper Premium 3-Seam 21 Natalie Cadet Hat Velvet Stretch 3-Seam Maddie Hat with Hair 6 Hayley Slouchy Cap 7 Sweater Knit 3-Seam Rosette 3-Seam 22 8 Claire ss Suede Micro Fleece 23Acce Halo Hair ories 9 Alex Cap 24 Turban Tie 10 Flurry Fleece Sleep Cap 25 Wired Headband Comfort Sleep Cap 26 Braided Headband 27 Simply Secure Headband Knit Headbands 11 r 28 Caps & Liners 12Sca Brook Scarfves Cool Wick Cap & Swim Turban 13 Brooklyn Scarf (Solid Selection) 14 Brooklyn Scarf (Patterned Selection) 15 Ellie Scarf Band 16 Zoey Scarf 1 As you make your way through your own journey of healing, Hats with Heart hopes to be with you all the way. Our desire is to help restore dignity & confidence in your life, allowing you to embrace a more positive outlook. We strive to provide products of the highest quality that are fashion forward and accessible. Each hat is created with a vision of femininity and elegance, attributes exemplified by the women who wear them. Navy *C FM-04 Face Masks Black *C FM-09 Aluminum nose piece, b adjustable elastics for ears. Climbing Vines *C FM-05 Available in 2 Sizes: Regular & Large Clear Vision *C FM-06 Espresso Batik *C FM-43 Stone Blue Batik *C FM-50 Glistening Waves *C FM-56 Silver-Lined Violets *C FM-57 Amethyst Batik *C FM-63 2 *C=100% Cotton 3-Seam Original Sizes: Small or Medium/Large #310 Designed to provide style and grace.b Worn by itself or with our accessories. -

Heritage Traditions

Heritage Traditions 2020 PRODUCT CATALOGUE HERITAGE TRADITIONS 2020 HT HERITAGE TRADITIONS 2020 ABOUT CONTENTS Page 4 --------- Peaky Panel Caps Page 68 --------- Mohair Look Scarves Page 6 --------- Duck Bill Caps Page 72 ---------- Union Jack Scarves Page 8 --------- Newsboy Caps Page 73 --------- Basket Weave Snoods Page 13 -------- Tweed Earflap Cap Page 74 --------- Tartan Mohair Scarves Page 14 --------- Flat Caps Page 75 --------- Tartan Mohair Blanket Page 18 --------- Tweed Baseball Caps Page 76 --------- Boucle Tweed Scarves Page 20 --------- Borg Trim Trappers Page 78 --------- Tartan Scarves Page 21 --------- Tweed Skip Caps Page 82 --------- Wool Herringbone Scarves Page 22 --------- Twill Skip Caps Page 84 --------- UJ Wool Scarves Page 23 ---------- Aviator Hats Page 85 --------- Wool Serapes Page 24 ---------- Check Baseball Caps Page 86 --------- Double Faced Wool Scarves Page 26 ---------- Pork Pie Hats Page 87 --------- Tartan Merino Scarves Page 28 ---------- Trilby Hats Page 88 --------- Gauze Scarves Page 30 ---------- Linen Panel Caps Page 90 --------- Seed Stitch Blanket Scarves Page 32 --------- Deer Hunter Caps Page 92 --------- Tweed Waistcoats Page 34 --------- Fisherman Wool Mix Beanies Page 94 --------- Tweed Bag Charms Page 36 --------- Twist Beanies Page 96 --------- Lapel Pin Set Page 38 --------- Chunky Fair Isle Collection Page 97 --------- Heritage Cufflinks Page 40 ---------- Rib Pom Pom Hats Page 98 --------- Mens Tweed Gloves Page 42 ----------- Ladies Newsboy Caps Page 100 -------- Mens Stud Strap