Identity and Influence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes and Topics: Synopsis of Taranatha's History

SYNOPSIS OF TARANATHA'S HISTORY Synopsis of chapters I - XIII was published in Vol. V, NO.3. Diacritical marks are not used; a standard transcription is followed. MRT CHAPTER XIV Events of the time of Brahmana Rahula King Chandrapala was the ruler of Aparantaka. He gave offerings to the Chaityas and the Sangha. A friend of the king, Indradhruva wrote the Aindra-vyakarana. During the reign of Chandrapala, Acharya Brahmana Rahulabhadra came to Nalanda. He took ordination from Venerable Krishna and stu died the Sravakapitaka. Some state that he was ordained by Rahula prabha and that Krishna was his teacher. He learnt the Sutras and the Tantras of Mahayana and preached the Madhyamika doctrines. There were at that time eight Madhyamika teachers, viz., Bhadantas Rahula garbha, Ghanasa and others. The Tantras were divided into three sections, Kriya (rites and rituals), Charya (practices) and Yoga (medi tation). The Tantric texts were Guhyasamaja, Buddhasamayayoga and Mayajala. Bhadanta Srilabha of Kashmir was a Hinayaist and propagated the Sautrantika doctrines. At this time appeared in Saketa Bhikshu Maha virya and in Varanasi Vaibhashika Mahabhadanta Buddhadeva. There were four other Bhandanta Dharmatrata, Ghoshaka, Vasumitra and Bu dhadeva. This Dharmatrata should not be confused with the author of Udanavarga, Dharmatrata; similarly this Vasumitra with two other Vasumitras, one being thr author of the Sastra-prakarana and the other of the Samayabhedoparachanachakra. [Translated into English by J. Masuda in Asia Major 1] In the eastern countries Odivisa and Bengal appeared Mantrayana along with many Vidyadharas. One of them was Sri Saraha or Mahabrahmana Rahula Brahmachari. At that time were composed the Mahayana Sutras except the Satasahasrika Prajnaparamita. -

A Hackathon for Classical Tibetan

A Hackathon for Classical Tibetan Orna Almogi1, Lena Dankin2*, Nachum Dershowitz2,3, Lior Wolf2 1Universität Hamburg, Germany 2Tel Aviv University, Israel 3Institut d’Études Avancées de Paris, France *Corresponding author: Lena Dankin, [email protected] Abstract We describe the course of a hackathon dedicated to the development of linguistic tools for Tibetan Buddhist studies. Over a period of five days, a group of seventeen scholars, scientists, and students developed and compared algorithms for intertextual alignment and text classification, along with some basic language tools, including a stemmer and word segmenter. Keywords Tibetan; Buddhist studies; hackathon; stemming; segmentation; intertextual alignment; text classification. I INTRODUCTION In February 2016, a group of four Tibetologists (from the University of Hamburg), one digital humanities scholar (from Europe), and twelve computer scientists (from Israel and Europe) got together in Kibbutz Lotan in the Arava region of Israel with the stated goal of developing algorithmic methods for advancing Tibetan Buddhist textual studies. Participants were either recruited by the organizers or responded to an announcement on several mailing lists. See Figure 1. Most of the computer scientists had background in machine learning, and a few of them also had experience with natural language processing (NLP) research, but without any prior experience with Tibetan texts. The computer scientist organizers were quite familiar with programming workshops and contests and thought that the challenges presented by Tibetan texts would pose an ideal opportunity to explore the hackathon format. The hackathon is a short and intense event where computer scientists collaborate to develop software. For that purpose, it was essential to recruit as many software developers as possible. -

Yoga of Hevajra

Y oga of H evajra Practice of the Y uan K hans? Zoltán Cser Dharma Gate Buddhist College, Budapest Premise1 In the article of Shen Weirong we read2: “It has been widely accepted that Tibetan tantric Buddhism was very popular at the court of the great Mongol khans, yet little is known about the details of the Buddhist teaching that were taught and practiced enthusiastically in and outside the Mongol court of the Yuan dynasty. Due to the prevailing misconception that it was the tantric practice of Tibetan Buddhism, notoriously epitomized in the so-called Secret Teach ing of Supreme Bliss mimi daxile fa; esoteric samádhi of great joy), that caused the rapid downfall of the great Mongol-Yuan dynasty.” “Twenty years ago, I. Christopher Beckwith drew attention to a till then unnoticed Yuan-period collection in Chinese on Tibetan tantric Buddhist teachings. This col lection is called ^ fill? itt Dacheng yaodao miji, or Secret Collection of Works on the Quintessential Path of the Mahdyana. It includes at least 28 texts devoted3 to ÜtH daoguo, or lam ‘bras (the path and fruit) teaching, which are particularly fa voured by the Sa skya pa sect, and to da shouyin, or Mahdmudra. According to the publisher’s preface, this collection became a basic teachings text of the esoteric school in China, and from the Yuan through the Ming and Manchu Qing dynasties down to the present day it has been revered as a ‘sacred classic of the esoteric school.’ This collection attributed to Phagpa lama (1235-1280).” Let us see first of all the historical background, how the Khans were initiated into Hevajra tantra, one of the highest teaching in Buddhism. -

Chariot of Faith Sekhar Guthog Tsuglag Khang, Drowolung

Chariot of Faith and Nectar for the Ears A Guide to: Sekhar Guthog Tsuglag Khang Drowolung Zang Phug Tagnya Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition 1632 SE 11th Avenue Portland, OR 97214 USA www.fpmt.org © 2014 Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system or technologies now known or developed, without permission in writing from the publisher. Set in Goudy Old Style 12/14.5 and BibleScrT. Cover image over Sekhar Guthog by Hugh Richardson, Wikimedia Com- mons. Printed in the USA. Practice Requirements: Anyone may read this text. Chariot of Faith and Nectar for the Ears 3 Chariot of Faith and Nectar for the Ears A Guide to Sekhar Guthog, Tsuglag Khang, Drowolung, Zang Phug, and Tagnya NAMO SARVA BUDDHA BODHISATTVAYA Homage to the buddhas and bodhisattvas! I prostrate to the lineage lamas, upholders of the precious Kagyu, The pioneers of the Vajrayana Vehicle That is the essence of all the teachings of Buddha Shakyamuni. Here I will write briefly the story of the holy place of Sekhar Guthog, together with its holy objects. The Glorious Bhagavan Hevajra manifested as Tombhi Heruka and set innumerable fortunate ones in the state of buddhahood in India. He then took rebirth in a Southern area of Tibet called Aus- picious Five Groups (Tashi Ding-Nga) at Pesar.1 Without discourage- ment, he went to many different parts of India where he met 108 lamas accomplished in study and practice, such as Maitripa and so forth. -

VT Module6 Lineage Text Major Schools of Tibetan Buddhism

THE MAJOR SCHOOLS OF TIBETAN BUDDHISM By Pema Khandro A BIRD’S EYE VIEW 1. NYINGMA LINEAGE a. Pema Khandro’s lineage. Literally means: ancient school or old school. Nyingmapas rely on the old tantras or the original interpretation of Tantra as it was given from Padmasambhava. b. Founded in 8th century by Padmasambhava, an Indian Yogi who synthesized the teachings of the Indian MahaSiddhas, the Buddhist Tantras, and Dzogchen. He gave this teaching (known as Vajrayana) in Tibet. c. Systemizes Buddhist philosophy and practice into 9 Yanas. The Inner Tantras (what Pema Khandro Rinpoche teaches primarily) are the last three. d. It is not a centralized hierarchy like the Sarma (new translation schools), which have a figure head similar to the Pope. Instead, the Nyingma tradition is de-centralized, with every Lama is the head of their own sangha. There are many different lineages within the Nyingma. e. A major characteristic of the Nyingma tradition is the emphasis in the Tibetan Yogi tradition – the Ngakpa tradition. However, once the Sarma translations set the tone for monasticism in Tibet, the Nyingmas also developed a monastic and institutionalized segment of the tradition. But many Nyingmas are Ngakpas or non-monastic practitioners. f. A major characteristic of the Nyingma tradition is that it is characterized by treasure revelations (gterma). These are visionary revelations of updated communications of the Vajrayana teachings. Ultimately treasure revelations are the same dharma principles but spoken in new ways, at new times and new places to new people. Because of these each treasure tradition is unique, this is the major reason behind the diversity within the Nyingma. -

Ontology of Consciousness

Ontology of Consciousness Percipient Action edited by Helmut Wautischer A Bradford Book The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England ( 2008 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or me- chanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. MIT Press books may be purchased at special quantity discounts for business or sales promotional use. For information, please e-mail [email protected] or write to Special Sales Depart- ment, The MIT Press, 55 Hayward Street, Cambridge, MA 02142. This book was set in Stone Serif and Stone Sans on 3B2 by Asco Typesetters, Hong Kong, and was printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ontology of consciousness : percipient action / edited by Helmut Wautischer. p. cm. ‘‘A Bradford book.’’ Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-262-23259-3 (hardcover : alk. paper)—ISBN 978-0-262-73184-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Consciousness. 2. Philosophical anthropology. 3. Culture—Philosophy. 4. Neuropsychology— Philosophy. 5. Mind and body. I. Wautischer, Helmut. B105.C477O58 2008 126—dc22 2006033823 10987654321 Index Abaluya culture (Kenya), 519 as limitation of Turing machines, 362 Abba Macarius of Egypt, 166 as opportunity, 365, 371 Abhidharma in dualism, person as extension of matter, as guides to Buddhist thought and practice, 167, 454 10–13, 58 in focus of attention, 336 basic content, 58 in measurement of intervals, 315 in Asanga’s ‘‘Compendium of Abhidharma’’ in regrouping of elements, 335, 344 (Abhidharma-samuccaya), 67 in technical causality, 169, 177 in Maudgalyayana’s ‘‘On the Origin of shamanic separation from body, 145 Designations’’ Prajnapti–sastra,73 Action, 252–268. -

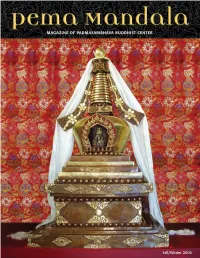

5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:02 PM Page 1

5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:02 PM Page 1 Fall/Winter 2006 5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:03 PM Page 2 Volume 5, Fall/Winter 2006 features A Publication of 3 Letter from the Venerable Khenpos Padmasambhava Buddhist Center Nyingma Lineage of Tibetan Buddhism 4 New Home for Ancient Treasures A long-awaited reliquary stupa is now at home at Founding Directors Ven. Khenchen Palden Sherab Rinpoche Padma Samye Ling, with precious relics inside. Ven. Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal Rinpoche 8 Starting to Practice Dream Yoga Rita Frizzell, Editor/Art Director Ani Lorraine, Contributing Editor More than merely resting, we can use the time we Beth Gongde, Copy Editor spend sleeping to truly benefit ourselves and others. Ann Helm, Teachings Editor Michael Nott, Advertising Director 13 Found in Translation Debra Jean Lambert, Administrative Assistant A student relates how she first met the Khenpos and Pema Mandala Office her experience translating Khenchen’s teachings on For subscriptions, change of address or Mipham Rinpoche. editorial submissions, please contact: Pema Mandala Magazine 1716A Linden Avenue 15 Ten Aspirations of a Bodhisattva Nashville, TN 37212 Translated for the 2006 Dzogchen Intensive. (615) 463-2374 • [email protected] 16 PBC Schedule for Fall 2006 / Winter 2007 Pema Mandala welcomes all contributions submitted for consideration. All accepted submissions will be edited appropriately 18 Namo Buddhaya, Namo Dharmaya, for publication in a magazine represent- Nama Sanghaya ing the Padmasambhava Buddhist Center. Please send submissions to the above A student reflects on a photograph and finds that it address. The deadline for the next issue is evokes more symbols than meet the eye. -

Buddhist Archeology in Mongolia: Zanabazar and the Géluk Diaspora Beyond Tibet

Buddhist Archeology in Mongolia: Zanabazar and the Géluk Diaspora beyond Tibet Uranchimeg Tsultemin, Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI) Uranchimeg, Tsultemin. 2019. “Buddhist Archeology in Mongolia: Zanabazar and the Géluk Dias- pora beyond Tibet.” Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review (e-journal) 31: 7–32. https://cross-currents.berkeley.edu/e-journal/issue-31/uranchimeg. Abstract This article discusses a Khalkha reincarnate ruler, the First Jebtsundampa Zanabazar, who is commonly believed to be a Géluk protagonist whose alliance with the Dalai and Panchen Lamas was crucial to the dissemination of Buddhism in Khalkha Mongolia. Za- nabazar’s Géluk affiliation, however, is a later Qing-Géluk construct to divert the initial Khalkha vision of him as a reincarnation of the Jonang historian Tāranātha (1575–1634). Whereas several scholars have discussed the political significance of Zanabazar’s rein- carnation based only on textual sources, this article takes an interdisciplinary approach to discuss, in addition to textual sources, visual records that include Zanabazar’s por- traits and current findings from an ongoing excavation of Zanabazar’s Saridag Monas- tery. Clay sculptures and Zanabazar’s own writings, heretofore little studied, suggest that Zanabazar’s open approach to sectarian affiliations and his vision, akin to Tsongkhapa’s, were inclusive of several traditions rather than being limited to a single one. Keywords: Zanabazar, Géluk school, Fifth Dalai Lama, Jebtsundampa, Khalkha, Mongo- lia, Dzungar Galdan Boshogtu, Saridag Monastery, archeology, excavation The First Jebtsundampa Zanabazar (1635–1723) was the most important protagonist in the later dissemination of Buddhism in Mongolia. Unlike the Mongol imperial period, when the sectarian alliance with the Sakya (Tib. -

Mindfulness and the Buddha's Noble Eightfold Path

Chapter 3 Mindfulness and the Buddha’s Noble Eightfold Path Malcolm Huxter 3.1 Introduction In the late 1970s, Kabat-Zinn, an immunologist, was on a Buddhist meditation retreat practicing mindfulness meditation. Inspired by the personal benefits, he de- veloped a strong intention to share these skills with those who would not normally attend retreats or wish to practice meditation. Kabat-Zinn developed and began con- ducting mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) in 1979. He defined mindful- ness as, “the awareness that emerges through paying attention on purpose, in the present moment, and non-judgmentally to the unfolding of experience moment to moment” (Kabat-Zinn 2003, p. 145). Since the establishment of MBSR, thousands of individuals have reduced psychological and physical suffering by attending these programs (see www.unmassmed.edu/cfm/mbsr/). Furthermore, the research into and popularity of mindfulness and mindfulness-based programs in medical and psychological settings has grown exponentially (Kabat-Zinn 2009). Kabat-Zinn (1990) deliberately detached the language and practice of mind- fulness from its Buddhist origins so that it would be more readily acceptable in Western health settings (Kabat-Zinn 1990). Despite a lack of consensus about the finer details (Singh et al. 2008), Kabat-Zinn’s operational definition of mindfulness remains possibly the most referred to in the field. Dozens of empirically validated mindfulness-based programs have emerged in the past three decades. However, the most acknowledged approaches include: MBSR (Kabat-Zinn 1990), dialectical behavior therapy (DBT; Linehan 1993), acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT; Hayes et al. 1999), and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT; Segal et al. -

And Daemonic Buddhism in India and Tibet

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 The Raven and the Serpent: "The Great All- Pervading R#hula" Daemonic Buddhism in India and Tibet Cameron Bailey Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE RAVEN AND THE SERPENT: “THE GREAT ALL-PERVADING RHULA” AND DMONIC BUDDHISM IN INDIA AND TIBET By CAMERON BAILEY A Thesis submitted to the Department of Religion in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Religion Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2012 Cameron Bailey defended this thesis on April 2, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Bryan Cuevas Professor Directing Thesis Jimmy Yu Committee Member Kathleen Erndl Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For my parents iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank, first and foremost, my adviser Dr. Bryan Cuevas who has guided me through the process of writing this thesis, and introduced me to most of the sources used in it. My growth as a scholar is almost entirely due to his influence. I would also like to thank Dr. Jimmy Yu, Dr. Kathleen Erndl, and Dr. Joseph Hellweg. If there is anything worthwhile in this work, it is undoubtedly due to their instruction. I also wish to thank my former undergraduate advisor at Indiana University, Dr. Richard Nance, who inspired me to become a scholar of Buddhism. -

THE SECURITISATION of TIBETAN BUDDHISM in COMMUNIST CHINA Abstract

ПОЛИТИКОЛОГИЈА РЕЛИГИЈЕ бр. 2/2012 год VI • POLITICS AND RELIGION • POLITOLOGIE DES RELIGIONS • Nº 2/2012 Vol. VI ___________________________________________________________________________ Tsering Topgyal 1 Прегледни рад Royal Holloway University of London UDK: 243.4:323(510)”1949/...” United Kingdom THE SECURITISATION OF TIBETAN BUDDHISM IN COMMUNIST CHINA Abstract This article examines the troubled relationship between Tibetan Buddhism and the Chinese state since 1949. In the history of this relationship, a cyclical pattern of Chinese attempts, both violently assimilative and subtly corrosive, to control Tibetan Buddhism and a multifaceted Tibetan resistance to defend their religious heritage, will be revealed. This article will develop a security-based logic for that cyclical dynamic. For these purposes, a two-level analytical framework will be applied. First, the framework of the insecurity dilemma will be used to draw the broad outlines of the historical cycles of repression and resistance. However, the insecurity dilemma does not look inside the concept of security and it is not helpful to establish how Tibetan Buddhism became a security issue in the first place and continues to retain that status. The theory of securitisation is best suited to perform this analytical task. As such, the cycles of Chinese repression and Tibetan resistance fundamentally originate from the incessant securitisation of Tibetan Buddhism by the Chinese state and its apparatchiks. The paper also considers the why, how, and who of this securitisation, setting the stage for a future research project taking up the analytical effort to study the why, how and who of a potential desecuritisation of all things Tibetan, including Tibetan Buddhism, and its benefits for resolving the protracted Sino- Tibetan conflict. -

Recounting the Fifth Dalai Lama's Rebirth Lineage

Recounting the Fifth Dalai Lama’s Rebirth Lineage Nancy G. Lin1 (Vanderbilt University) Faced with something immensely large or unknown, of which we still do not know enough or of which we shall never know, the author proposes a list as a specimen, example, or indication, leaving the reader to imagine the rest. —Umberto Eco, The Infinity of Lists2 ncarnation lineages naming the past lives of eminent lamas have circulated since the twelfth century, that is, roughly I around the same time that the practice of identifying reincarnating Tibetan lamas, or tulkus (sprul sku), began.3 From the twelfth through eighteenth centuries it appears that incarnation or rebirth lineages (sku phreng, ’khrungs rabs, etc.) of eminent lamas rarely exceeded twenty members as presented in such sources as their auto/biographies, supplication prayers, and portraits; Dölpopa Sherab Gyeltsen (Dol po pa Shes rab rgyal mtshan, 1292–1361), one such exception, had thirty-two. Among other eminent lamas who traced their previous lives to the distant Indic past, the lineages of Nyangrel Nyima Özer (Nyang ral Nyi ma ’od zer, 1124–1192) had up 1 I thank the organizers and participants of the USF Symposium on The Tulku Institution in Tibetan Buddhism, where this paper originated, along with those of the Harvard Buddhist Studies Forum—especially José Cabezón, Jake Dalton, Michael Sheehy, and Nicole Willock for the feedback and resources they shared. I am further indebted to Tony K. Stewart, Anand Taneja, Bryan Lowe, Dianna Bell, and Rae Erin Dachille for comments on drafted materials. I thank the Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation for International Scholarly Exchange for their generous support during the final stages of revision.