Moles & Chapman SGA2019 Abstract

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Individual History Report.Pdf

Bridget ALLWELL Version 10 Jul 2020 Bridget ALLWELL (1881-1922) is the grandmother of Richard Michael WHITCHURCH-BENNETT Name: Bridget ALLWELL Father: James ALLWELL (1853-1928) Mother: Margaret MAHER (c. 1857-1920) Individual Events and Attributes Birth 21 Feb 1881 Tombreane, WIC, Ireland1,2 Baptism 22 Feb 1881 Tomacork, WIC, Ireland3 1901 Census of Ireland 31 Mar 1901 Tombreane, WIC, Ireland4 1911 Census of Ireland 2 Apr 1911 Raheengraney, WIC, Ireland5 Death 5 Sep 1922 Raheengraney, WIC, Ireland6,7 Burial 7 Sep 1922 Clonegal, CAR, Ireland8 Marriage Spouse James O'NEILL (1886-1957) Children James O'NEILL (1913-1989) Anne O'NEILL (1915-1980) John O'NEILL (1917-1987) Margaret Mary O'NEILL (1919-2009) Bridget O'NEILL (1921-2000) Marriage 9 Aug 1910 Tomacork, WIC, Ireland9,10 Individual Note She was born on 21 February 1881 at Tombreane, Co Wicklow, Ireland, the daughter of James and Margaret Allwell (née Maher). Her birth was registered on 5 March 1881 by her father. She was baptised on 22 February 1881 at St Brigid Church, Tomacork, Co Wicklow. The Parish Baptism Register records the Rev. J Sinnott and Kate Hennessy as being her godparents. She is recorded in the 1901 Census of Ireland living at Tombreane, Co Wicklow at the home of Helena Jane Higginbotham. Household Return Form A (Number B1) records her name as Bridget Alwell; being the Servant of the Head of Family; Roman Catholic; able to Read & Write; aged 20; Female; Cook Domestic Servant; Not Married; and born in County Wicklow. This was a farmhouse with several farm outbuildings. -

Gorey Ferns Carnew Camolin Kiltealy Bunclody Sliabh Bhuí Ballycanew

9 STONES CYCLE TRAIL ROUTE LEGEND WICKLOW 9 Inch Nine Stones Cycle Route N11 National Primary Road Kilanerin Regional Road Carnew Castletown Local Road Follow these signs: 6 Craanford Ballon Gorey Clonegal 8 N80 Askamore CARLOW 1 YOU ARE HERE Kildavin Sliabh Bhuí Bunclody 2 N11 Courtown Ballyroebuck Nine Stones Clohamon 7 Kilmyshall WEXFORD 5 Camolin Ballycanew N80 4 ROUTE ELEVATION (METRES) N11 Total Distance: 118km Route Information at these Locations Total Elevation: 1600m Ballygarrett 1600 1500 i i 1400 Ferns 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1300 1200 1100 Ballycarney 1000 900 3 800 700 600 500 400 The Harrow 300 200 Kiltealy 100 N11 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 110 0 Bunclody Carnew Bunaithe ar Chontae Loch Garman, tá Lúb Rothaíochta na Naoi Bun Clóidí, na Naoi gCloch, Cill Téile, Fearna, An Bráca, Baile Uí The Nine Stones Cycling Loop Trail is a County Wexford based Bunclody, The Nine Stones, Kiltealy, Ferns, The Harrow, gCloch ina bhall den ghrúpa a dtugtar Conairí Loch Garman air. Chonnmhaí, Guaire, An Chloch, Cam Eolaing, Sliabh Bhuí, Carn an Cycling Trail within the Wexford Trails family. The Trail traverses Ballycanew, Gorey, Clogh, Camolin, Sliabh Bhuí, Carnew and ROUTE SECTIONS & DISTANCES Trasnaíonn sé Contae Loch Garman den chuid is mó ach téann Bhua agus ar ais go Bun Clóidí. County Wexford for the most part, but also enters parts of returns to Bunclody. isteach i gContae Cheatharlach agus i gContae Chill Mhantáin Ar na príomh-shuíomhanna ar an lúb tá Bun Clóidí inar féidir County Carlow and County Wicklow. -

The Kidds of Ireland

THE KIDDS OF IRELAND Part II The Dublin and Southern Ireland Kidds by Franklin Kidd (1890-1974) Unpublished manuscript typescript; this version dates from 1972-73, based on statements made in it this searchable text version made using Omnipage ocr from manuscript images (from website http://www.kiddgenealogy.net/), by William S F Kidd 3/2012 with subsequent extensive visual editing to remove typographical recognition errors; the pagination of the original typescript is retained in this conversion, in order to facilitate comparison with the original. Most of the underlined text in the original has not been marked in this version. Headings have instead been distinguished by using contrasting font styles. Text indentations similarly have not been retained. If you miss them, or the underlined body text, feel free to take a copy and to surrender the time needed to put them in! I have added a few footnotes to make clear where I have made any changes from the original typescript text; most of these point either to minor typographical errors, or in a few cases to an obvious error in a date, probably originating from misreading the source used while typing. Such footnotes are all explicitly marked as added to distinguish them clearly from Franklin Kidd's footnotes. (as an editorial observation, for a typewriter manuscript, there are astonishingly few typographical errors, even though the first of them occurs on page 1....) In Chs. 2 and 3, the name typed Leighton has in every case been replaced (without note) by Leighlin (which occurs correctly everywhere in chs. 1, and 4-6 in this one context of Marriage Licence Bonds). -

GAA Competition Report

Wicklow Centre of Excellence Ballinakill Rathdrum Co. Wicklow. Rathdrum Co. Wicklow. Co. Wicklow Master Fixture List 2019 A67 HW86 15-02-2019 (Fri) Division 1 Senior Football League Round 2 Baltinglass 20:00 Baltinglass V Kiltegan Referee: Kieron Kenny Hollywood 20:00 Hollywood V St Patrick's Wicklow Referee: Noel Kinsella 17-02-2019 (Sun) Division 1 Senior Football League Round 2 Blessington 11:00 Blessington V AGB Referee: Pat Dunne Rathnew 11:00 Rathnew V Tinahely Referee: John Keenan Division 1A Senior Football League Round 2 Kilmacanogue 11:00 Kilmacanogue V Bray Emmets Gaa Club Referee: Phillip Bracken Carnew 11:00 Carnew V Éire Óg Greystones Referee: Darragh Byrne Newtown GAA 11:00 Newtown V Annacurra Referee: Stephen Fagan Dunlavin 11:00 Dunlavin V Avondale Referee: Garrett Whelan 22-02-2019 (Fri) Division 3 Football League Round 1 Hollywood 20:00 Hollywood V Avoca Referee: Noel Kinsella Division 1 Senior Football League Round 3 Baltinglass 19:30 Baltinglass V Tinahely Referee: John Keenan Page: 1 of 38 22-02-2019 (Fri) Division 1A Senior Football League Round 3 Annacurra 20:00 Annacurra V Carnew Referee: Anthony Nolan 23-02-2019 (Sat) Division 3 Football League Round 1 Knockananna 15:00 Knockananna V Tinahely Referee: Chris Canavan St. Mary's GAA Club 15:00 Enniskerry V Shillelagh / Coolboy Referee: Eddie Leonard 15:00 Lacken-Kilbride V Blessington Referee: Liam Cullen Aughrim GAA Club 15:00 Aughrim V Éire Óg Greystones Referee: Brendan Furlong Wicklow Town 16:15 St Patrick's Wicklow V Ashford Referee: Eugene O Brien Division -

IRISH GENEALOGY MATTERS (Volume 2 No

IRISH GENEALOGY MATTERS (Volume 2 No. 1, 2019) The newsletter of www.rootsireland.ie and the Irish Family History Foundation Research your Irish Ancestry at www.rootsireland.ie Welcome everyone to our first newsletter for 2019 in which we aim to keep you informed of the activities of the Irish Family History Foundation (IFHF) and our centres, as well as new features and updates on our website, www.rootsireland.ie. NEW RECORDS! • NEW RECORDS! • NEW RECORDS! Since our last newsletter, the following records have added to our database on www.rootsireland.ie • 18,000 records of various types (census substitutes and baptisms) for Counties Laois and Offaly; • East Galway records including Cappatagle & Kilreekil RC baptisms, 1766-1915; Woodford RC baptisms, 1909-1917; Civil records updated and extended; Roman Catholic marriages extended to 1917; • 18,500 civil marriage records for County Waterford, 1864-1912. Many more records are expected shortly, including the Roman Catholic registers for the parishes of Camolin and Adamstown, County Wexford, so keep your eyes open for more updates! We will notify those on our mailing list when these records are uploaded and available, so make sure to register to our mailing list to keep abreast with new additions to www.rootsireland.ie! Reginald’s Tower, Waterford, early twentieth century www.rootsireland.ie [email protected] EYE ON COUNTY CENTRES DERRY GENEALOGY’S INVOLVEMENT IN FORTHCOMING NOVEL Brian Mitchell of Derry Genealogy has been advising and assisting an American author, Harry Wenzel, who is currently writing a book on a ship named the Faithful Steward which was shipwrecked on its journey from Derry to Philadelphia in 1785. -

Marref-2015-Wicklow-Tally.Pdf

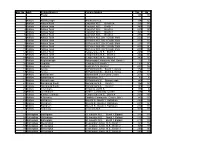

Box No LEA Polling District Polling Station Yes No Postal 188 137 1 Arklow Annacurragh Annacurra N.S. 134 127 2 Arklow Arklow Rock Carysfort N.S., Booth 5A 245 180 3 Arklow Arklow Town Carysfort N.S., Booth 1 345 102 4 Arklow Arklow Town Carysfort N.S., Booth 2 287 195 5 Arklow Arklow Town Carysfort N.S., Booth 3 363 113 6 Arklow Arklow Town Carysfort N.S., Booth 4 281 170 7 Arklow Arklow Town St Peters N.S. Bth 1 Castle Park 259 144 8 Arklow Arklow Town St Peters N.S. Bth 2 Castle Park 200 157 9 Arklow Arklow Town St Peters N.S. Bth 3 Castle Park 223 178 10 Arklow Arklow Town St Peters N.S. Bth 4 Castle Park 204 151 11 Arklow Arklow Town St Peters N.S. Bth 5 Castle Park 207 182 12 Arklow Arklow Town Templerainey N.S., Booth 1 247 135 13 Arklow Arklow Town Templerainey N.S., Booth 2 242 107 14 Arklow Arklow Town Templerainey N.S., Booth 3 240 115 15 Arklow Aughavanagh Askanagap Community Hall, Booth 1 42 54 16 Arklow Aughrim Aughrim N.S.,Booth 1 230 141 17 Arklow Aughrim Aughrim N.S.,Booth 2 221 146 18 Arklow Avoca St Patricks N.S., Booth 1, Avoca 172 110 19 Arklow Avoca St Patricks N.S., Booth 2, Avoca 236 111 20 Arklow Ballinaclash Ballinaclash Community Centre 255 128 21 Arklow Ballycoogue Ballycoogue N.S. 97 83 22 Arklow Barnacleagh St Patricks N.S., Barnacleagh 149 111 23 Arklow Barndarrig South Barndarrig N.S. -

The List of Church of Ireland Parish Registers

THE LIST of CHURCH OF IRELAND PARISH REGISTERS A Colour-coded Resource Accounting For What Survives; Where It Is; & With Additional Information of Copies, Transcripts and Online Indexes SEPTEMBER 2021 The List of Parish Registers The List of Church of Ireland Parish Registers was originally compiled in-house for the Public Record Office of Ireland (PROI), now the National Archives of Ireland (NAI), by Miss Margaret Griffith (1911-2001) Deputy Keeper of the PROI during the 1950s. Griffith’s original list (which was titled the Table of Parochial Records and Copies) was based on inventories returned by the parochial officers about the year 1875/6, and thereafter corrected in the light of subsequent events - most particularly the tragic destruction of the PROI in 1922 when over 500 collections were destroyed. A table showing the position before 1922 had been published in July 1891 as an appendix to the 23rd Report of the Deputy Keeper of the Public Records Office of Ireland. In the light of the 1922 fire, the list changed dramatically – the large numbers of collections underlined indicated that they had been destroyed by fire in 1922. The List has been updated regularly since 1984, when PROI agreed that the RCB Library should be the place of deposit for Church of Ireland registers. Under the tenure of Dr Raymond Refaussé, the Church’s first professional archivist, the work of gathering in registers and other local records from local custody was carried out in earnest and today the RCB Library’s parish collections number 1,114. The Library is also responsible for the care of registers that remain in local custody, although until they are transferred it is difficult to ascertain exactly what dates are covered. -

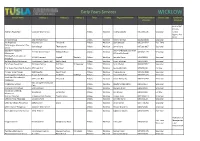

WICKLOW Service Name Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 Town County Registered Provider Telephone Number Service Type Conditions of Service Attached

Early Years Services WICKLOW Service Name Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 Town County Registered Provider Telephone Number Service Type Conditions of Service Attached Article 58G Child & Aisling's Playschool 61 Lower Main Street Arklow Wicklow Aisling Costello 086 3905336 Sessional Family Agency Act 2013 An Scoil Bheag 39A Wexford Road Arklow Wicklow Valerie Whelan 086 8236928 Sessional Ark Preschool Masonic Hall Ferrybank Arklow Wicklow Lily Dempsey 086 3844764 Part Time Ballyflanigan Montessori Pre- Barnacleagh Thomastown Arklow Wicklow Jenny Kane 087 6814867 Sessional school Blackberry Academy Dee Prendergast Sara Ryan The Old School House St Mary's Road Arklow Wicklow 089 4671175 Sessional Montessori & Esme McDowell Budding Tots Montessori 14 Holt Crescent Lugduff Tinahely Arklow Wicklow Jennifer Doyle 040 228959 Sessional Preschool Building Blocks Montessori Presbyterian Church Hall Dublin Road Arklow Wicklow Susan Whelton 040 233442 Sessional Early Days Pre-school Childcare Facility 3rd Floor Bridgewater Arklow Wicklow Karin Walker 083 0072852 Sessional First Steps Playschool & Creche 35 Cluain Ard Sea Road Arklow Wicklow Lesley McGrath 040 291919 Full Day Frances' Little Flowers Ballinheeshe Beach Road Arklow Wicklow Frances Burke 087 6564098 Sessional Grasshoppers Preschool Stoops Guesthouse Coollathn Shilleagh Arklow Wicklow Victoria Mulhall 087 6973124 Sessional Head Start Pre-school & Methodist Hall Ferrybank Arklow Wicklow Gillian Dempsey 086 2132256 Sessional Montessori Unit 1 Croghen Industrial Imagination Station Arklow Wicklow -

Local Electoral Area Boundary Committee 2018 County Wicklow

Local Electoral Area Boundary Committee 2018 County Wicklow William Winters 18 February 2018 1.0 Executive Summary The names and number of the five Municipal Districts in County Wicklow should remain the same. However, in line with the Terms of Reference(ToR), the boundaries should be refined to facilitate better local Government and Municipal Districts shall consist of one or more local electoral areas where appropriate or required by the ToR. 2014 2019 2019 Municipal District LEAs seats seats seats Arklow 6 6 Single LEA 6 Baltinglass 6 5 Single LEA 5 Bray Central 4 Bray 8 8 Bray Environs 4 Greystones 6 6 Single LEA 6 Wicklow 6 7 Single LEA 7 Total Seats 32 32 Total Seats 32 Figure 1: Proposed Municipal Districts and LEAs Page 1 of 8 2.0 Detailed Proposal 2.1 Arklow Municipal District (6 seats) Transfer the following Electoral Districts (EDs) from Baltinglass Municipal District to Arklow Municipal District: Aghowle, Ballinglen, Ballybeg, Carnew, Coolattin, Coolboy, Cronelea, Killinure, Money, Rath, Shillelagh, and Tinahely. Transfer the following EDs from Arklow Municipal District into Wicklow Municipal District: Knockrath, Ballinderry, Rathdrum, Dunganstown West, Dunganstown East. 2.2 Baltinglass Municipal District (5 seats) In accordance with article 6 of the terms of reference, the area should be reduced in size to avoid designating local electoral areas which are territorially very large or extend over very long distances. It is over 60km from end to end of the existing Municipal District, and in between, County Carlow separates Baltinglass from the southern settlements of Carnew, Tinahely and Shillelagh. In accordance with article 7(iv) I propose that exceptional circumstances exist for the creation of a single local electoral area with 5 members by transferring the following EDs from Baltinglass Municipal District to Arklow Municipal District: Aghowle, Ballinglen, Ballybeg, Carnew, Coolattin, Coolboy, Cronelea, Killinure, Money, Rath, Shillelagh, and Tinahely. -

4. Carnew Town Plan

Wicklow County Development Plan 2016‐2022 4. Carnew Town Plan 4.1 Context The settlement of Carnew is located in the south-western ‘finger’ of County Wicklow that protrudes between the adjoining counties of Carlow to the west and Wexford to the east. The county border with Wexford is only 1.2km from the eastern edge of Carnew, while the Carlow border is approximately 9km to the west of the town. In topographical terms the town of Carnew is at the fringe of the valley of the River Derry, which is a tributary of the River Slaney and flows in a north - south direction from Tinahely to Kildavin in Co. Carlow where it joins the Slaney. The R725 regional road that runs from Gorey in north-east Wexford to Carlow town is the main road through Carnew. The views from the Main Street westwards across the adjoining valley create the visual effect of ‘a gateway’ from north Wexford to south Wicklow and north east Carlow. Due to the location of Carnew at a juncture of three counties it is inevitable that the town has strong socio-economic and cultural links with the adjoining counties of Wexford and Carlow. The urban form of the town of Carnew provides for an expansive Main Street, with wide footpaths, laid out in a linear format. Coupled with the prominent position of the Church of Ireland, these features make up a conventional ‘Landlord Town’, built throughout Ireland during the 1800s. Two further built features in the town that reflect the ‘landlord influence’ in the spatial planning of the settlement over an extended period of time are two existing rows of old artisan dwellings that previously lay at the northern and western edges of Carnew, namely Coolattin Row and Brunswick Row respectively. -

Wicklow County Childcare Committee

Wicklow County Childcare Committee Newsletter Winter 2010 Inside this issue: ECCE Update In the first ECCE period, January to June, 83% of eligible children were enrolled in the Free Pre-school Year scheme. ECCE Update 1 From September it's estimated that 63,000 out of 67,000 (94%) are taking part. By 1 Playbus comparative European standards, it’s a very high level of participation in a very short time. Parent Seminars 2 Of the 63,000 children... New Childcare Facilities 3 83% are in sessional services, 9 ½% in Full Day care Road Safety 4 7 ½% in half day care, 95% attending 5 days a week, 2.5% 4 days and 2.5% 3 days Parenting 4 All Services have now received a letter from OMCYA confirming those children for whom they’re Childminding News 5 receiving the capitation fee. Mentoring Support 6 Payments in 2011 Dormant Accounts 6 38 week services will receive 2 payments: for 11 weeks from January to March, and 11 weeks from April to June 6 Service Reviews 50 week services will receive 3 payments: for 13 weeks from January to March, 12 weeks from April to June and 8 weeks from July to August The County Wicklow Playbus arrives! and more. There’s also a separate room on weeks with a full programme starting in the Bus for group and one to one meetings. 2011. Its capital cost being funded with the The Co Wicklow Playbus is one of only four support of the Dormant Accounts Fund via Playbuses in the country so it’s something of the Office of the Minister for Children and a coup for the County to get one! It’s been Youth Affairs, Playbus is supported through driven by an inter-agency steering the National Play Policy which aims to committee with representatives from County create better play opportunities for children; Wicklow VEC, Wicklow County Childcare it’s also intended to provide services to Committee, FAS, HSE, Wicklow County support the family as a whole, particularly Council, Arklow Springboard, Wicklow Child those parents and children experiencing and Family Project and East Wicklow Youth 'The Playbus with some members of it's social exclusion. -

Near Cambridge. CB2 5LW the KIDDS of IRELAND Part II Dubli

- 37 - By Franklin Kidd1 Appl.eby Cottage, 24 Woodlands Road, Gt. Shel.ford~ near Cambridge. CB2 5LW THE KIDDS OF IRELAND Part II Dublin and Southern Ireland Kidde 1 CHAPTER 4 ... The Cranemo~e branch Evidence from various sources had pointed clearly to Joseph Kidd, born 1765, died 1839, aged 74, Aghade Register, as being an early progenitor of this line. The dates indicate he was of fifth generation. I could not fill the gap back to the first three generations for a long time. This Joseph Kidd paid Tithe on 42 acres at Cranemore in 1825. The Church near Cranemore is Kildavin Church. These places are in Co. Carlow, about 2 miles west of Clonegall, which is close to the junction of the Wicklow Wexford Carlow County borders. Joseph's burial 1839 is in _the Register of Aghade Kilbride about 3 miles to the north, and he is there described as of Kildreenagh. Later, his son John (sixth generation 1802-1876 Customs House Register) occupied Kildreenagh. Kildreenagh is some eight miles away to the west near _Bagenalstown and Leighlinbridge. John also was of Cranemore when young, presumably before his father went to Kildreenagh. John was subse quently evicted from Kildreenagh, and went to Ba.llywilliam, a long way south near New Ross. In 1850 Griffiths valuations shew him there with 93 acres, and he died there. (Customs House Register). In 1850 there is no record in Griffiths valuations of a Kidd occupying the Cranemore holding. However, after John's death (his dates are 1892-1876 and he died aged 74 as did his father Joseph) his eldest.