Wicklow County Council Development at Shillelagh, Co. Wicklow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Individual History Report.Pdf

Bridget ALLWELL Version 10 Jul 2020 Bridget ALLWELL (1881-1922) is the grandmother of Richard Michael WHITCHURCH-BENNETT Name: Bridget ALLWELL Father: James ALLWELL (1853-1928) Mother: Margaret MAHER (c. 1857-1920) Individual Events and Attributes Birth 21 Feb 1881 Tombreane, WIC, Ireland1,2 Baptism 22 Feb 1881 Tomacork, WIC, Ireland3 1901 Census of Ireland 31 Mar 1901 Tombreane, WIC, Ireland4 1911 Census of Ireland 2 Apr 1911 Raheengraney, WIC, Ireland5 Death 5 Sep 1922 Raheengraney, WIC, Ireland6,7 Burial 7 Sep 1922 Clonegal, CAR, Ireland8 Marriage Spouse James O'NEILL (1886-1957) Children James O'NEILL (1913-1989) Anne O'NEILL (1915-1980) John O'NEILL (1917-1987) Margaret Mary O'NEILL (1919-2009) Bridget O'NEILL (1921-2000) Marriage 9 Aug 1910 Tomacork, WIC, Ireland9,10 Individual Note She was born on 21 February 1881 at Tombreane, Co Wicklow, Ireland, the daughter of James and Margaret Allwell (née Maher). Her birth was registered on 5 March 1881 by her father. She was baptised on 22 February 1881 at St Brigid Church, Tomacork, Co Wicklow. The Parish Baptism Register records the Rev. J Sinnott and Kate Hennessy as being her godparents. She is recorded in the 1901 Census of Ireland living at Tombreane, Co Wicklow at the home of Helena Jane Higginbotham. Household Return Form A (Number B1) records her name as Bridget Alwell; being the Servant of the Head of Family; Roman Catholic; able to Read & Write; aged 20; Female; Cook Domestic Servant; Not Married; and born in County Wicklow. This was a farmhouse with several farm outbuildings. -

Gorey Ferns Carnew Camolin Kiltealy Bunclody Sliabh Bhuí Ballycanew

9 STONES CYCLE TRAIL ROUTE LEGEND WICKLOW 9 Inch Nine Stones Cycle Route N11 National Primary Road Kilanerin Regional Road Carnew Castletown Local Road Follow these signs: 6 Craanford Ballon Gorey Clonegal 8 N80 Askamore CARLOW 1 YOU ARE HERE Kildavin Sliabh Bhuí Bunclody 2 N11 Courtown Ballyroebuck Nine Stones Clohamon 7 Kilmyshall WEXFORD 5 Camolin Ballycanew N80 4 ROUTE ELEVATION (METRES) N11 Total Distance: 118km Route Information at these Locations Total Elevation: 1600m Ballygarrett 1600 1500 i i 1400 Ferns 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1300 1200 1100 Ballycarney 1000 900 3 800 700 600 500 400 The Harrow 300 200 Kiltealy 100 N11 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 110 0 Bunclody Carnew Bunaithe ar Chontae Loch Garman, tá Lúb Rothaíochta na Naoi Bun Clóidí, na Naoi gCloch, Cill Téile, Fearna, An Bráca, Baile Uí The Nine Stones Cycling Loop Trail is a County Wexford based Bunclody, The Nine Stones, Kiltealy, Ferns, The Harrow, gCloch ina bhall den ghrúpa a dtugtar Conairí Loch Garman air. Chonnmhaí, Guaire, An Chloch, Cam Eolaing, Sliabh Bhuí, Carn an Cycling Trail within the Wexford Trails family. The Trail traverses Ballycanew, Gorey, Clogh, Camolin, Sliabh Bhuí, Carnew and ROUTE SECTIONS & DISTANCES Trasnaíonn sé Contae Loch Garman den chuid is mó ach téann Bhua agus ar ais go Bun Clóidí. County Wexford for the most part, but also enters parts of returns to Bunclody. isteach i gContae Cheatharlach agus i gContae Chill Mhantáin Ar na príomh-shuíomhanna ar an lúb tá Bun Clóidí inar féidir County Carlow and County Wicklow. -

The Kidds of Ireland

THE KIDDS OF IRELAND Part II The Dublin and Southern Ireland Kidds by Franklin Kidd (1890-1974) Unpublished manuscript typescript; this version dates from 1972-73, based on statements made in it this searchable text version made using Omnipage ocr from manuscript images (from website http://www.kiddgenealogy.net/), by William S F Kidd 3/2012 with subsequent extensive visual editing to remove typographical recognition errors; the pagination of the original typescript is retained in this conversion, in order to facilitate comparison with the original. Most of the underlined text in the original has not been marked in this version. Headings have instead been distinguished by using contrasting font styles. Text indentations similarly have not been retained. If you miss them, or the underlined body text, feel free to take a copy and to surrender the time needed to put them in! I have added a few footnotes to make clear where I have made any changes from the original typescript text; most of these point either to minor typographical errors, or in a few cases to an obvious error in a date, probably originating from misreading the source used while typing. Such footnotes are all explicitly marked as added to distinguish them clearly from Franklin Kidd's footnotes. (as an editorial observation, for a typewriter manuscript, there are astonishingly few typographical errors, even though the first of them occurs on page 1....) In Chs. 2 and 3, the name typed Leighton has in every case been replaced (without note) by Leighlin (which occurs correctly everywhere in chs. 1, and 4-6 in this one context of Marriage Licence Bonds). -

GAA Competition Report

Wicklow Centre of Excellence Ballinakill Rathdrum Co. Wicklow. Rathdrum Co. Wicklow. Co. Wicklow Master Fixture List 2019 A67 HW86 15-02-2019 (Fri) Division 1 Senior Football League Round 2 Baltinglass 20:00 Baltinglass V Kiltegan Referee: Kieron Kenny Hollywood 20:00 Hollywood V St Patrick's Wicklow Referee: Noel Kinsella 17-02-2019 (Sun) Division 1 Senior Football League Round 2 Blessington 11:00 Blessington V AGB Referee: Pat Dunne Rathnew 11:00 Rathnew V Tinahely Referee: John Keenan Division 1A Senior Football League Round 2 Kilmacanogue 11:00 Kilmacanogue V Bray Emmets Gaa Club Referee: Phillip Bracken Carnew 11:00 Carnew V Éire Óg Greystones Referee: Darragh Byrne Newtown GAA 11:00 Newtown V Annacurra Referee: Stephen Fagan Dunlavin 11:00 Dunlavin V Avondale Referee: Garrett Whelan 22-02-2019 (Fri) Division 3 Football League Round 1 Hollywood 20:00 Hollywood V Avoca Referee: Noel Kinsella Division 1 Senior Football League Round 3 Baltinglass 19:30 Baltinglass V Tinahely Referee: John Keenan Page: 1 of 38 22-02-2019 (Fri) Division 1A Senior Football League Round 3 Annacurra 20:00 Annacurra V Carnew Referee: Anthony Nolan 23-02-2019 (Sat) Division 3 Football League Round 1 Knockananna 15:00 Knockananna V Tinahely Referee: Chris Canavan St. Mary's GAA Club 15:00 Enniskerry V Shillelagh / Coolboy Referee: Eddie Leonard 15:00 Lacken-Kilbride V Blessington Referee: Liam Cullen Aughrim GAA Club 15:00 Aughrim V Éire Óg Greystones Referee: Brendan Furlong Wicklow Town 16:15 St Patrick's Wicklow V Ashford Referee: Eugene O Brien Division -

Comhairle Cathrach Phort Lairge Waterford City Council

COMHAIRLE CATHRACH PHORT LAIRGE WATERFORD CITY COUNCIL The Waterford Archaeological and Historical Society and the editor of DECIES gratefully acknowledge the generous sponsorship of Waterford City Council towards the publication costs of this journal. COMHAIRLE CONTAE PHORT LAIRGE WATERFORD COUNTY COUNCIL The Waterford Archaeological and Historical Society and the editor of DECIES gratefully acknowledge the generous sponsorship of Waterford County Council towards the publica- tion costs of this journal. Cover Illustrations Frorzt Cover: Signed lithograph of Thomas Francis Meagher by Edwin Hayes, one of a series that Meagher signed and presented to his friends while in prison following the 1848 Rebellion. Courtesy, Waterford Museum of Treasures. Back Cover: Viking sword and decorated weight found at Woodstown during archaeological excavations in advance of construction of the N25 Waterford Bypass. Courtesy, Waterford Museum of Treasures. ISSN 1393-3116 Published by The Waterford Archaeological and Historical Society Printed by Naas Printing Ltd., Naas, Co. Kildare (045-872092). Decies 65 PAGE Editorial ........................................................................................................................ vii List of Contributors ....................................................................................................... ix The Dungarvan Valley Caves Project: Second Interim Report Cdilin 0 ~risceoil,Richard Jennings ........................................................................... 1 Copper Coin of -

IRISH GENEALOGY MATTERS (Volume 2 No

IRISH GENEALOGY MATTERS (Volume 2 No. 1, 2019) The newsletter of www.rootsireland.ie and the Irish Family History Foundation Research your Irish Ancestry at www.rootsireland.ie Welcome everyone to our first newsletter for 2019 in which we aim to keep you informed of the activities of the Irish Family History Foundation (IFHF) and our centres, as well as new features and updates on our website, www.rootsireland.ie. NEW RECORDS! • NEW RECORDS! • NEW RECORDS! Since our last newsletter, the following records have added to our database on www.rootsireland.ie • 18,000 records of various types (census substitutes and baptisms) for Counties Laois and Offaly; • East Galway records including Cappatagle & Kilreekil RC baptisms, 1766-1915; Woodford RC baptisms, 1909-1917; Civil records updated and extended; Roman Catholic marriages extended to 1917; • 18,500 civil marriage records for County Waterford, 1864-1912. Many more records are expected shortly, including the Roman Catholic registers for the parishes of Camolin and Adamstown, County Wexford, so keep your eyes open for more updates! We will notify those on our mailing list when these records are uploaded and available, so make sure to register to our mailing list to keep abreast with new additions to www.rootsireland.ie! Reginald’s Tower, Waterford, early twentieth century www.rootsireland.ie [email protected] EYE ON COUNTY CENTRES DERRY GENEALOGY’S INVOLVEMENT IN FORTHCOMING NOVEL Brian Mitchell of Derry Genealogy has been advising and assisting an American author, Harry Wenzel, who is currently writing a book on a ship named the Faithful Steward which was shipwrecked on its journey from Derry to Philadelphia in 1785. -

Moles & Chapman SGA2019 Abstract

Detrital gold, heavy minerals and sediment geochemistry elucidate auriferous mineralization in southeast Ireland Moles, Norman R. School of Environment and Technology, University of Brighton, UK Chapman, Robert J. Ores and Mineralization Group, School of Earth and Environment, University of Leeds, UK Abstract. Recently published Tellus geochemical data 2 Geology and mineralization for sediment fines in SE Ireland show extensive Au anomalies in north Wexford, but few anomalies in Southeast Ireland comprises a NE-SW oriented belt of Wicklow despite historical extraction from the Goldmines Cambrian – Ordovician sedimentary and volcanic rocks River. Discovery of bedrock sources is hampered by that were deformed and metamorphosed during later glacial dispersion and scarce bedrock exposure. Here we Palaeozoic orogenic events (Gallagher et al. 1994). describe a novel approach to characterizing regional gold Lower Ordovician thick laminated mudstones of the metallogeny which involves the synthesis of data sets ‘Ribband Group’ were followed by clastic sediments and from stream sediment surveys, analysis of heavy mineral volcanic rocks of the Duncannon Group (Brück et al. concentrates (HMCs) and detrital gold. Mineralogical 1979). In Wicklow the latter incorporates the Avoca characterization of HMCs and 2160 gold grains from 40 Volcanic Group (AVG) which comprises dominantly localities in the auriferous region provides a clear rhyolitic lavas, chloritic tuffs and slaty mudstones. indication of proximity of gold to source and genetic A major period of shearing towards the end of the origins. Detrital gold in the south of the region (Wexford) Caledonian orogeny generated NE-oriented deformation is most likely derived from the widespread stratabound zones, one of which occurs in the Avoca – Goldmines Au-As-Fe-S reported by exploration companies, whereas River area. -

2016 – 2022 Record of Protected Structures

COUNTY Record of Protected Structures 2016 – 2022 WICKLOW COUNTY DEVELOPMENT PLAN Comhairle Contae Chill Mhantáin DECEMBER 2016 Wicklow County Council - Record of Protected Structures Each development plan must include policy objectives to protect structures or parts of structures of special interest within its functional area under Section 10 of the Planning and Development Act, 2000. The primary means of achieving this objective is for the planning authority to compile and maintain a record of protected structures to be included in the development plan. A planning authority is obliged to include in the Record of Protected Structures every structure which, in its opinion, is of special architectural, historical, archaeological, artistic, cultural, scientific, social or technical interest. A ‘protected structure’ is defined as any structure or specified part of a structure, which is included in the Record of Protected Structures. A structure is defined by the Planning and Development Act, 2000 as ‘any building, structure, excavation, or other thing constructed or made on, in or under any land, or any part of a structure’. In relation to a protected structure, the meaning of the term ‘structure’ is expanded to include: (a) the interior of the structure; (b) the land lying within the curtilage of the structure; (c) any other structures lying within that curtilage and their interiors, and (d) all fixtures and features which form part of the interior or exterior of the above structures. Where indicated in the Record of Protected Structures, protection may also include any specified feature within the attendant grounds of the structure which would not otherwise be included. -

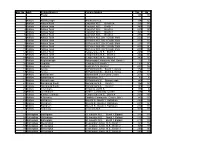

Marref-2015-Wicklow-Tally.Pdf

Box No LEA Polling District Polling Station Yes No Postal 188 137 1 Arklow Annacurragh Annacurra N.S. 134 127 2 Arklow Arklow Rock Carysfort N.S., Booth 5A 245 180 3 Arklow Arklow Town Carysfort N.S., Booth 1 345 102 4 Arklow Arklow Town Carysfort N.S., Booth 2 287 195 5 Arklow Arklow Town Carysfort N.S., Booth 3 363 113 6 Arklow Arklow Town Carysfort N.S., Booth 4 281 170 7 Arklow Arklow Town St Peters N.S. Bth 1 Castle Park 259 144 8 Arklow Arklow Town St Peters N.S. Bth 2 Castle Park 200 157 9 Arklow Arklow Town St Peters N.S. Bth 3 Castle Park 223 178 10 Arklow Arklow Town St Peters N.S. Bth 4 Castle Park 204 151 11 Arklow Arklow Town St Peters N.S. Bth 5 Castle Park 207 182 12 Arklow Arklow Town Templerainey N.S., Booth 1 247 135 13 Arklow Arklow Town Templerainey N.S., Booth 2 242 107 14 Arklow Arklow Town Templerainey N.S., Booth 3 240 115 15 Arklow Aughavanagh Askanagap Community Hall, Booth 1 42 54 16 Arklow Aughrim Aughrim N.S.,Booth 1 230 141 17 Arklow Aughrim Aughrim N.S.,Booth 2 221 146 18 Arklow Avoca St Patricks N.S., Booth 1, Avoca 172 110 19 Arklow Avoca St Patricks N.S., Booth 2, Avoca 236 111 20 Arklow Ballinaclash Ballinaclash Community Centre 255 128 21 Arklow Ballycoogue Ballycoogue N.S. 97 83 22 Arklow Barnacleagh St Patricks N.S., Barnacleagh 149 111 23 Arklow Barndarrig South Barndarrig N.S. -

Under 7 & 9 Hurling & Football Fixtures Give Respect, Get Respect

The Garden County Go Games Little Buds Programme A Place where all Children Bloom Under 7 & 9 Hurling & Football Fixtures Give Respect, Get Respect Recommendations for Age Groups 2017 Under 7 Under 9 Players born in 2010 & 2011 Players born in 2008 & 2009 Football Friday Night Clubs/18 Clubs Saturday Morning Clubs/18 Clubs Avoca Kilbride/Lacken AGB Blessington Barndarrig Valleymount St Patricks Hollywood Rathnew Dunlavin Ashford Donard/Glen Avondale Stratford/Grangecon Laragh Baltinglass Ballinacor Kiltegan An Tochar Knockananna Kilmacanogue Ballymanus Enniskerry Tinahely Bray Emmets Shillelagh Fergal Ogs Coolkenno Eire Og Greystones Carnew Kilcoole Coolboy Newtown Annacurra Newcastle Aughrim Hurling Friday Night Clubs / 16 Clubs Barndarrig Kilmacanogue Kiltegan St Patricks Kilcoole Tinahely Avondale Bray Emmets Kilcoole Carnew Fergal Ogs Glenealy Aughrim Eire Og Greystones ARP Stratford/Grangecon/Hollywood/Dunlavin The Full “Garden County Go Games Little Buds Programme” for 2017 will be sponsored by the Wicklow People Wicklow People are going to give us a lot of coverage but we need photos taken with the advertising board that will be supplied to each club. Club Go Games PR person to be appointed to send in photos for Twitter, Facebook and Wicklow People To the following Email Address shall be used immediately after each home blitz when returning photographs. We need all clubs corporation on this to ensure we have a good quality section in the Wicklow People each week. The onus is on the Home club to take the photographs of all teams -

The Armstrong Papers P6-Part2

The Armstrong Papers P6 Part II Kemmis of Ballinacor, County Wicklow Armstrong of Natal, South Africa Documents of Unidentified Provenance Maps Portraits and Drawings Postcards and Letterheads Press Cuttings University of Limerick Library and Information Services University of Limerick Special Collections The Armstrong Papers Reference Code: IE 2135 P6 Title: The Armstrong Papers Dates of Creation: 1662-1999 Level of Description: Fonds Extent and Medium: 133 boxes, 2 outsize items (2522 files) CONTEXT Name of Creator(s): The Armstrong family of Moyaliffe Castle, county Tipperary, and the related families of Maude of Lenaghan, county Fermanagh; Everard of Ratcliffe Hall, Leicestershire; Kemmis of Ballinacor, county Wicklow; Russell of Broadmead Manor, Kent; and others. Biographical History: The Armstrongs were a Scottish border clan, prominent in the service of both Scottish and English kings. Numerous and feared, the clan is said to have derived its name from a warrior who during the Battle of the Standard in 1138 lifted a fallen king onto his own horse with one arm after the king’s horse had been killed under him. In the turbulent years of the seventeenth century, many Armstrongs headed to Ireland to fight for the Royalist cause. Among them was Captain William Armstrong (c. 1630- 1695), whose father, Sir Thomas Armstrong, had been a supporter of Charles I throughout the Civil War and the Commonwealth rule, and had twice faced imprisonment in the Tower of London for his support for Charles II. When Charles II was restored to power, he favoured Captain William Armstrong with a lease of Farneybridge, county Tipperary, in 1660, and a grant of Bohercarron and other lands in county Limerick in 1666. -

Language Notes on Baronies of Ireland 1821-1891

Database of Irish Historical Statistics - Language Notes 1 Language Notes on Language (Barony) From the census of 1851 onwards information was sought on those who spoke Irish only and those bi-lingual. However the presentation of language data changes from one census to the next between 1851 and 1871 but thereafter remains the same (1871-1891). Spatial Unit Table Name Barony lang51_bar Barony lang61_bar Barony lang71_91_bar County lang01_11_cou Barony geog_id (spatial code book) County county_id (spatial code book) Notes on Baronies of Ireland 1821-1891 Baronies are sub-division of counties their administrative boundaries being fixed by the Act 6 Geo. IV., c 99. Their origins pre-date this act, they were used in the assessments of local taxation under the Grand Juries. Over time many were split into smaller units and a few were amalgamated. Townlands and parishes - smaller units - were detached from one barony and allocated to an adjoining one at vaious intervals. This the size of many baronines changed, albiet not substantially. Furthermore, reclamation of sea and loughs expanded the land mass of Ireland, consequently between 1851 and 1861 Ireland increased its size by 9,433 acres. The census Commissioners used Barony units for organising the census data from 1821 to 1891. These notes are to guide the user through these changes. From the census of 1871 to 1891 the number of subjects enumerated at this level decreased In addition, city and large town data are also included in many of the barony tables. These are : The list of cities and towns is a follows: Dublin City Kilkenny City Drogheda Town* Cork City Limerick City Waterford City Database of Irish Historical Statistics - Language Notes 2 Belfast Town/City (Co.