Urban Upheaval in India: the 1974 Nav Nirman Riots in Gujarat Author(S): Dawn E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Political Historiography of Modern Gujarat

The Political Historiography of Modern Gujarat Tannen Neil Lincoln ISBN 978-81-7791-236-4 © 2016, Copyright Reserved The Institute for Social and Economic Change, Bangalore Institute for Social and Economic Change (ISEC) is engaged in interdisciplinary research in analytical and applied areas of the social sciences, encompassing diverse aspects of development. ISEC works with central, state and local governments as well as international agencies by undertaking systematic studies of resource potential, identifying factors influencing growth and examining measures for reducing poverty. The thrust areas of research include state and local economic policies, issues relating to sociological and demographic transition, environmental issues and fiscal, administrative and political decentralization and governance. It pursues fruitful contacts with other institutions and scholars devoted to social science research through collaborative research programmes, seminars, etc. The Working Paper Series provides an opportunity for ISEC faculty, visiting fellows and PhD scholars to discuss their ideas and research work before publication and to get feedback from their peer group. Papers selected for publication in the series present empirical analyses and generally deal with wider issues of public policy at a sectoral, regional or national level. These working papers undergo review but typically do not present final research results, and constitute works in progress. Working Paper Series Editor: Marchang Reimeingam THE POLITICAL HISTORIOGRAPHY OF MODERN -

Name Address Amount of Unpaid Dividend (Rs.) Mukesh Shukla Lic Cbo‐3 Ka Samne, Dr

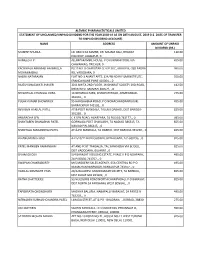

ALEMBIC PHARMACEUTICALS LIMITED STATEMENT OF UNCLAIMED/UNPAID DIVIDEND FOR THE YEAR 2018‐19 AS ON 28TH AUGUST, 2019 (I.E. DATE OF TRANSFER TO UNPAID DIVIDEND ACCOUNT) NAME ADDRESS AMOUNT OF UNPAID DIVIDEND (RS.) MUKESH SHUKLA LIC CBO‐3 KA SAMNE, DR. MAJAM GALI, BHAGAT 110.00 COLONEY, JABALPUR, 0 HAMEED A P . ALUMPARAMBIL HOUSE, P O KURANHIYOOR, VIA 495.00 CHAVAKKAD, TRICHUR, 0 KACHWALA ABBASALI HAJIMULLA PLOT NO. 8 CHAROTAR CO OP SOC, GROUP B, OLD PADRA 990.00 MOHMMADALI RD, VADODARA, 0 NALINI NATARAJAN FLAT NO‐1 ANANT APTS, 124/4B NEAR FILM INSTITUTE, 550.00 ERANDAWANE PUNE 410004, , 0 RAJESH BHAGWATI JHAVERI 30 B AMITA 2ND FLOOR, JAYBHARAT SOCIETY 3RD ROAD, 412.50 KHAR WEST MUMBAI 400521, , 0 SEVANTILAL CHUNILAL VORA 14 NIHARIKA PARK, KHANPUR ROAD, AHMEDABAD‐ 275.00 381001, , 0 PULAK KUMAR BHOWMICK 95 HARISHABHA ROAD, P O NONACHANDANPUKUR, 495.00 BARRACKPUR 743102, , 0 REVABEN HARILAL PATEL AT & POST MANDALA, TALUKA DABHOI, DIST BARODA‐ 825.00 391230, , 0 ANURADHA SEN C K SEN ROAD, AGARPARA, 24 PGS (N) 743177, , 0 495.00 SHANTABEN SHANABHAI PATEL GORWAGA POST CHAKLASHI, TA NADIAD 386315, TA 825.00 NADIAD PIN‐386315, , 0 SHANTILAL MAGANBHAI PATEL AT & PO MANDALA, TA DABHOI, DIST BARODA‐391230, , 0 825.00 B HANUMANTH RAO 4‐2‐510/11 BADI CHOWDI, HYDERABAD, A P‐500195, , 0 825.00 PATEL MANIBEN RAMANBHAI AT AND POST TANDALJA, TAL.SANKHEDA VIA BODELI, 825.00 DIST VADODARA, GUJARAT., 0 SIVAM GHOSH 5/4 BARASAT HOUSING ESTATE, PHASE‐II P O NOAPARA, 495.00 24‐PAGS(N) 743707, , 0 SWAPAN CHAKRABORTY M/S MODERN SALES AGENCY, 65A CENTRAL RD P O 495.00 -

Daily Current Affairs

Daily Current Affairs Date: 11 JANUARY 2021 1. With which PSU, Indian Renewable Energy 6. Name the app, which was recently launched by Development Agency Limited, IREDA signed a Jammu and Kashmir Lieutenant Governor Manoj Sinha Memorandum of Understanding for providing its with the Departmental Vigilance Officers Portal of J&K technical expertise in developing renewable energy Anti-Corruption Bureau? projects? (A) Avabuddh Nagrik (B) Saavdhan Nagrik (A) NTPC Limited (C) Hoshiyar Nagrik (D) Satark Nagrik (B) SJVN (E) Sachet Nagrik (C) PGCIL (D) ONGC 7. What is the name of the indigenously developed (E) NHPC Limited guided multi-launch rocket system by the Pakistani Army, which recently successfully conducted a test 2. Which public agency has designed and developed the flight? recently launched Digital Calendar and Diary of (A) Vijay-1 (B) Jay-1 Government of India? (C) Jeet-1 (D) Ajey-1 (A) Press Information Bureau (E) Fatah-1 (B) Bureau of outreach and communication (C) Regional Outreach Bureau 8. Recently the government of which country has (D) Registrar of Newspapers for India committed Official Development Assistance loan of (E) None of these 2113 crore rupees for a programme loan to support India's efforts at providing social assistance to the poor 3. Name the former Indian striker who has been and vulnerable households, severely impacted by the appointed as the first deputy general secretary of All COVID-19 pandemic? India Football Federation (AIFF) after the sports body (A) Japan (B) China decided to create a new post in its hierarchy? (C) South Korea (D) North Korea (A) Abhishek Yadav (E) Singapore (B) Syed Rahim Nabi (C) Deepak Mondal 9. -

Gujarat – BJP – Police – Law and Order – Elections

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: IND32487 Country: India Date: 12 November 2007 Keywords: India – Gujarat – BJP – Police – Law and order – Elections This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Is there any information on who controls the Sonarda/Gandhinagar area and who would have controlled this area in 2004? 2. My understanding is that the state government not local districts are responsible for law and order. Please provide any information on this. 3. Please provide information on the 2007 elections in Gujarat, and whether the BJP is still in power. 4. Is there any information on attacks in Gujarat, on BJP supporters from Congress associated people, with police inaction from 2002 to current? RESPONSE 1. Is there any information on who controls the Sonarda/Gandhinagar area and who would have controlled this area in 2004? Very little information could be located on the village of Sonarda and no information could be located which referred to the political situation in Sonarda specifically. Alternatively, a great deal of information is available on the political situation in the city of Gandhinagar and its surrounding district (Gandhinagar is the Gujarat state capital). -

Pragati Sahakari Bank Ltd

To find your name press ctrl + F and type your name and press enter PRAGATI SAHAKARI BANK LTD. Unclaimed Deposit Amount Transfer to the Depositer Education and Awareness Fund Scheme 2014 (DEAF – 2015) on 30 November 2016 NAME ADDRESS UDAISINGH KHUMANSINGH BARIA ROOM NO. 99 D, PANCHVATI SOC., GORWA, , VADODARA-0 UDASINGH CHANDRASINGH RATHOD DOLATPUR, PO. SHAHPUR, , VADODARA-0 UDASINH MAHIJIBHAI PARMAR RAMSHARA, HALOL, , PANCHMAHAL-0 UDAY AKNTH DADPE A.C.W LTD., , , VADODARA-3 UDAY BALRAMBHAI PATEL A/1, VAMIL PARK SOC., GOTRI ROAD, , VADODARA-0 UDAY EKNATH DADPE 705, ANAND BHAVAN, OPP. POLO GROUND, , VADODARA-1 23.ASHOK SOCIETY, OPP.LIONS HALL, RACE COURCE ROAD, UDAY NAVINCHANDRA PATEL VADODARA-0 FLAT NO.4 MANGAL BHUVAN, NIRMALA CONVENT SCHOOL UDAY RASIKBHAI CHINOY RAOD, , RAJKOT-0 UDAY THAKORBHAI PATEL 15, PRATAPGUNJ, , , VADODARA-0 UDAYSING CHANDUBHAI PARMAR PILOL, NANAPURA, , VADODARA-0 UDAYSING GAMBHIRSING RAVAL GARASIA MAHOLLA, GORWA, , VADODARA-0 UDAYSING SHABHAI PARMAR PANALEV, TAJPURA, HALOL, , PANCHMAHAL-0 UDAYSINGBHAI LOVEGANBHAI VASAVA F/54, ALEMBIC COLONY, , , VADODARA-0 UDAYSINGH DABHAI PARMAR SURAJPURA, RAVALIYA, HALOL, , PANCHMAHAL-0 UDAYSINGH SHIVASINGH PADHIYAR SINDHROT, , , VADODARA-0 UDESINGH KUMANSINGH CHAUHAN GUJ.HOUS. BOARD, GORWA, , VADODARA-0 F-1,GUJARAT KRUSHI UNIVERSITY, MODEL FARM, , VADODARA- UDESINH D PARMAR 390003 UJALA G BISWAS 11-SATYAM APPT.,OPP-REFINARY, ROAD,GORWA,BARODA, , --0 'UPKAR'XAVIERS NAGAR, ST.XAVIER'S ROAD ANAND, , ANAND- UJVALA PARSOTTAMDAS CHRISTIAN 388001 UKABHAI CHHAGANBHAI MALI B/H.E.S.I., GORWA, , VADODARA-0 UKABHAI G MISTRY 13-FH KRISHNASHANTI SOC., AKOTA, , VADODARA-0 7, "SHAKUNTAL" VITHAL SOC., SOC. B/H JAI RATNA BULDG, , ULHAS JANARDAN CHITRE VADODARA-0 A/321, KALPNA SOC., NEW SURYA NAGAR, WAGHODIA, , UMA BALKRISHNA SHAH VADODARA-0 UMA SUNIL SHUKLA C-10,GOKUL NAGAR, VASNA ROAD, , VADODARA-390020 UMA VIDYALAYA C/O,SHRI KADVA PATIDAR KEL. -

Chimanbhai Patel Institute of Journalism and Communication (CP IJC) Grooming Gen-Next for Holistic Development

Volume : I, Issue : I Year : 2019-2020 सयं एवं तयम् Chimanbhai Patel Institute of Journalism and Communication (CP IJC) Grooming Gen-Next for holistic development. “ Your principle should be to see everything and say nothing. The world changes so rapidly that if you want to get on, you cannot afford to align yourself with any person or point of view. “ – Kushwant Singh Kudos to all the Top Ten Rankers in Gujarat University BJMC Semester I Exam Nov-Dec 2019 1 “I aspire to change the current journalistic system of the country and dream to travel each nook and corner of the globe.” Acharya Akshay Dharmendra SGPA : 7.77 2 3 “I aspire to enter into the eld “Setting my goal towards being a of print media.” good communicator, writer and a successful entrepreneur in future.” Bhinde Vaidehi Chandrakant Kriplani Khushi Nanak SGPA : 7.39 SGPA : 7.31 4 5 “My dream is to become a promising “My aim is to inuence people lm maker in the media industry.” through the tip of my pen.” Gala Ashish Jayesh Pancholi Rudri Premalbhai SGPA : 7.28 SGPA : 7.23 6 6 “Man is born to suffer and die “I rmly believe that ones life becomes and what befalls him is rather complete when one becomes a greatest catastrophic, there is no denying level of inspiration for others and that’s that it is the nal end but it is our my goal.” job to deny it all the way along.” Patel Aahana Unmesh Shaikh Kaif Kaiser Haseebahshan SGPA : 7.09 SGPA : 7.09 7 8 “My dream is to become a crime reporter “I aspire to become an Art and a social activist as well to raise the Director in future.” voice of the unheard.” Dhanukar Siddhi Sanjay Patel Drashti Mukeshbhai SGPA : 7.05 SGPA : 6.98 9 10 “Kya lekar aye the, kya lekar “My dream is to become an eminent jaoge, Lekin apna naam duniya photographer.” me chhod kar jao. -

Interview List for Selection of Appointment of Notaries in the State of Gujarat

Interview List for Selection of Appointment of Notaries in the State of Gujarat Area of Practice S.No. Name File No. Father Name Address Enrollment no. Applied for 2, ManubhailS Chawl, Nisarahmed N- Ahmedabad Gulamrasul Near Patrewali Masjid G/370/1999 1 Gulamrasul 11013/2011/2016- Metropolitan City A.Samad Ansari Gomtipur Ahmedabad Dt.21.03.99 Ansari NC Gujarat380021 N- Gulamnabi At & Po.Anand, B, Nishant Ms. Merunisha G/1267/1999 2 Anand Distt. 11013/2012/2016- Chandbhai Colony, Bhalej Road, I Gulamnabi Vohra Dt.21.03.99 NC Vohra Anand Gujarat-388001 333, Kalpna Society, N- Deepakbhai B/H.Suryanagar Bus G/249/1981 3 Vadodara Distt. 11013/2013/2016- Bhikubhai Shah Bhikubhai Shah Stand, Waghodia Road, Dt.06.05.81 NC Vadodara Gujarat- N- Jinabhai Dhebar Faliya Kundishery Ms. Bakula G/267/1995 4 Junagadh 11013/2014/2016- Jesabhai Arunoday Junagadh Jinabhai Dayatar Dt.15.03.95 NC Dayatar Dist.Junagadh Gujarat- Mehta N- Vill. Durgapur, Tal. G/944/1999 5 Bharatkumar Mandvi-Kutch 11013/2015/2016- Hirji Ajramal Manvdi-Kutch Gujarat Dt.21.03.99 Hirji NC N- At.Kolavna, Ta.Amod, Patel Mohamedali G/857/1998 6 Bharuch Distt. 11013/2016/2016- Patel Yakub Vali Distt.Bharuch, Gujarat- Yakub Dt.09.10.98 NC 392140 N- Gandhi 6-B/1, Ajay Wadi, Gandhi Hitesh G/641/2000 7 Bhavnagar 11013/2017/2016- Vasantray Subhashnagar Bhavnagar Vasantray Dt.05.05.2000 NC Prabhudas Gujarat- 319, Suthar Faliyu, At. & N- Nileshkumar Jhagadiya, Dist. Motibhai PO Avidha, Ta. Jhagadiya, G/539/1995 8 11013/2018/2016- Motibhai Desai Bharuch Laxmidas Desai Dist. -

BJP's Rise to Power

GUJARAT BJP's Rise to Power Ghanshyam Shah The BJP's victory in the 1995 assembly elections in Gujarat was not due to a temporary wave. The party has slowly built its base among the OBCs, tribals and dalits in the state. Nevertheless, for a majority of the people who voted for the BJP, its 'Hindutva' plank remained a major consideration for extending support to the party. This was particularly true of the urban middle class voters. I the other hand, displayed no will to fight slightly improved its position in the 1985 elections with a political agenda. During the elections despite the sympathy wave for THIS is not for the first time that the last five years most of the party leaders had Rajiv Gandhi. It bagged 11 seats, and 14.6 Congress(l) has lost power in Gujarat. With spent their energy to get political offices and per cent of the votes. The Congress was the support of Kisan Majdoor Lok Paksha other favours. After winning power in routed in the 1990 assembly poll, securing (KMLP), the Janata Morcha (United Front) Madhya Pradesh in 1993 the party bosses only 33 seats in a house of 182 members. formed the government in 1975.' It was the believed that somehow they would come to Its votes declined from 56 per cent in 1985 dissident Congress leader Chimanbhai Patel power again in 1995. They continued to to a mere 31 per cent in 1990, The Janata who, having been expelled from the party bank upon old strategies and calculations. Dal and the BJP, with partial electoral for his "anti-party" activities after his Individually, each party boss hoped to adjustment on some seats against the resignation as the chief minister, had continue in power and fought for. -

Botched-Up Development and Electoral Politics in India.Pdf

SPECIAL ARTICLE Botched-up Development and Electoral Politics in India Prakash Kashwan The debates about the general election campaign in he debates during the general election campaign in India have often pitted “development” against India often pitted “development” against secularism. To the extent that such dichotomy worked to the advan- secularism. In the process, questions about the T tage of the conservative Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), the tex- emergence of alternative political formations have been ture of the debates signifi es a success of its prime ministerial pushed to the sidelines. This article argues that a candidate, Narendra Modi’s skills in setting the agenda for development versus secular polarisation of national this election.1 Notwithstanding the attempts on the part of some commentators to introduce nuances to these debates, the debates reflects a gross simplification of the politics of debating space was overwhelmed by a presidential style duel development in independent India. Through an between Narendra Modi and Rahul Gandhi. In the process, examination of the historical antecedents of the debates over questions related to the nature of social welfare contemporary dominance of the political right in Gujarat and economic development policies were sidelined. Even more importantly, questions about the emergence of alternative and by drawing on recent research, this article makes political formations were bulldozed over. two interrelated arguments. First, it shows that the This paper argues that this state of affairs, that is, a develop- success of the right is inextricably linked to the ment versus secular polarisation of national debates refl ects a botched-up development priorities of the past several gross simplifi cation of the politics of development in independ- ent India. -

P 3 Chirayu R Amin F-10/195, Race Course Circle, Gotri

P 3 CHIRAYU R AMIN P 5 P 6 F-10/195, RACE COURSE CIRCLE, RAMESHBHAI CHIMANLAL SHAH HASMUKH SHANTILAL SHAH GOTRI ROAD, 37/A, 1ST FLOOR, PURSHOTTAM 10, ISHAVASYAM, SEVASI MAHAPURA VADODARA NAGAR, ROAD, 390007 BPC ROAD, MAHAPURA, ALKAPURI, VADODARA VADODARA 391101 390007 P 9 P 10 P 11 JANAK BIPINBHAI PATEL ANUJ LALITBHAI PATEL AMUL V JIKAR 11 PRATAPGUNJ, NANDALAYA, VIKAS NAGAR SOC, 14 A HARIBHAKTI COLONY, NR, NATRAJ CINEMA, OLD PADRA ROAD, BH. ALKAPURI TEL. EXCHANGE, PRATAPGUNJ, VADODARA RACE COURSE, VADODARA 390020 VADODARA 390002 390007 P 12 P 13 P 15 RAMAN P PATEL LALIT K MODI SUCHITA S VICHARE 43, VISHWAKUNJ SOC, STERLING APTS 17TH FLOOR, SAI KRUPA, BAROT MOHALLA, B/H BUDDHDEV COLONY, KARELI PEDDAR ROAD, SALATWADA, BAUG, BOMBAY VADODARA KARELIBAUG, 26 390001 VADODARA 390018 P 16 P 17 JWALANT KANDARPRAI DESAI VORA SHITAL "AAROH", 2, JAYDEEP SOCIETY, 14 B UDYOGNAGAR, NR. TULSIDHAM APPTS, O/S PANIGATE NR AURVEDIC, MANJALPUR, PANIGATE, VADODARA VADODARA 390011 390019 VP 3 UPENDRABHAI M PATEL VP 4 VP 5 KRISHNARPAN, SAMIR ESTATE, DR JITENDRA T PATEL BHIKHABHAI C MAJMUNDAR SEVASI ROAD, UMA NURSING HOME, KRISHNA KRIPA, VADODARA RAOPURA, MEHTA POLE, 391101 VADODARA MANDVI, 390001 VADODARA 390006 VP 6 VP 8 VP 9 NIRANJAN VITTHAL DESAI JAYMALA DEEPAKSINH CHAVAN RANJITSINH S CHAVAN 2, ARADHANA SOC., A/14, HARI DHAM DUPLEX, 9TH FLOOR, BBC TOWER, VISHWAS COLONY, NEAR HARI- NAGAR, SAYAJIGUNJ, ALKAPURI, GOTRI ROAD, VADODARA VADODARA VADODARA 390005 390005 390007 VP 11 VP 12 VP 14 NIKUNJ R KADAKIA SATISH H GANDHI GIRISHBHAI C PATEL SHANTINAGAR B-15TH FLOOR, 2, ARADHNA SOCIETY, 4 RAMBHAI MANSIONS, FLAT 155, 98-NEPEAN SEA ROAD, B/H NATIONAL PLAZA, SAYAJIGUNJ, SEA ROAD, R C DUTT ROAD, VADODARA MUMBAI VADODARA 390005 400006 NA VP 19 VP 21 VP 22 SHREEKANT MANOHAR BHATE SHEKHAR DATTATRAY KARNIK PRANAV MANUBHAI PARIKH "YASHOBHASKAR" , R.K. -

Annexure-2 List of Colleges of Ahmedabad-Vadodara Dist Which

Annexure-2 List of Colleges of Ahmedabad-Vadodara District which have Submitted Information about Anti-Ragging Committee. Sr. Name of College Address Of the College Code No. No. 1 Smt. Laxmiben & Shri Opp. Law Garden,Ellis bridge, 02 Chimanbhai Arts College Ahmedabad-380006 2 Govt. Arts College Shri K.K.Shastri Educational Campus, 384 Khokhara, Maninagar, Ahmedabad-380008 3 Shri L.A.Shah Law College Opp. Law Garden, Ellis Bridge, Ahmedabad- 002 380006. 4 S.K.U.B. Samiti (Dabhoi) Arts At- & Po. Pipaliya, 220 and Smt. N.C.Zaveri Ta. Waghodia, Dist. Vadodara – 391760 Commerce College, (Pipaliya) 5 L.D.Arts College Amrutlal Hargovandas Campus Navrangpura 05 Ahmedabad – 380009 6 B.M.Inst. of Mental Health Nr. Nehru Bridge, Ashram Road Ahmedabad - 380009 7 Shri Janki Vallabh Arts college Muval – 391430 Ta. Padra, Dist. Vadodara 214 & Shri Manubhai patel commerce college 8 Khyati Inst. Of Physiotherapy 15, Cantonment Shahibaug, Ahmedabad - 380003 9 Shree Kishandas Kikani Arts Dhandhuka – 382460, Dist. Ahmedabad 077 & Commerce College 10 C.C.Sheth College of Navgujarat Campus, Ashram Road, 147 Commerce Ahmedabad - 380014 11 H.A.College of Commerce Opp. Law Garden, Ellis bridge, 025 Ahmedabad - 380006 12 Shri K.K.Shashtri Government Shri K.K.Shashtri Education Campus, Khokhra 340 Commerce College Road, Maninagar (East) Ahmedabad - 380008 13 Ahmedabad Municipal Bhalakia Mill Compound, Khokhra, 497 Corporation Medical Ahmedabad - 380008 Education Trust (A.M.C MET) 14 Sheth R.A.College of Arts & Vidyagauri Nilkanth Marg, Khanpur, 085 Commerce Ahmedabad - 380001 15 Shree Sahajanand Vanijya Ambawadi, Ahmedabad - 380015 189 Mahavidyalaya 16 Sardar Vallabhbhai Arts Relief Road, Pattharkuva, Ahmedabad - 380001 College 17 Sheth Ranchhodlal Acharatlal Vidyagauri Nilkanth Road, Khanpur, 086 College of Science Ahmedabad - 380001 18 M.P.Arts & M.H. -

Download History of Patidars

Presented by: “Together we move forward” The history of the Leuva Patidars begins with the arrival of Aryans in India about 1500 BC. It is a story as old as Hinduism itself. It is a fascinating journey that traverses through many countries with its highs and lows. The events and the places we lived in has shaped our character. In return, we have impacted the culture and economies of those places. Throughout this journey a few things will remain unchanged, like our hard working nature, ‘never say die’ attitude, insistence for truth, the co-operative nature and a strong sense of brotherhood within the community. These very characteristics will result in the rise of the Patidar communities in Gujarat, Africa, UK and their present success in the USA. This is an attempt to educate our children of our rich heritage that they can be proud of. It is also an effort to teach them valuable lessons from our history. May long they carry the torch of our cultural heritage. May long they live in peace and prosperity… India has the mighty Himalayan mountain range on the N & E. It consist of over 100 mountains over 23,600 ft. To the west of Himalayas are the Karakoram & Hindu Kush mountains. In the N-E parts of Pakistan are located the lush plains of Punjab. These plains are accessible through Khyber pass on the Afghan-Pakistan border. Most migrants to India came through this Pass & settled in the Punjab region. The first humans arrived from Africa to India about 50,000 years ago.