Botched-Up Development and Electoral Politics in India.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STATISTICAL REPORT GENERAL ELECTIONS, 2004 the 14Th LOK SABHA

STATISTICAL REPORT ON GENERAL ELECTIONS, 2004 TO THE 14th LOK SABHA VOLUME III (DETAILS FOR ASSEMBLY SEGMENTS OF PARLIAMENTARY CONSTITUENCIES) ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA NEW DELHI Election Commission of India – General Elections, 2004 (14th LOK SABHA) STATISCAL REPORT – VOLUME III (National and State Abstracts & Detailed Results) CONTENTS SUBJECT Page No. Part – I 1. List of Participating Political Parties 1 - 6 2. Details for Assembly Segments of Parliamentary Constituencies 7 - 1332 Election Commission of India, General Elections, 2004 (14th LOK SABHA) LIST OF PARTICIPATING POLITICAL PARTIES PARTYTYPE ABBREVIATION PARTY NATIONAL PARTIES 1 . BJP Bharatiya Janata Party 2 . BSP Bahujan Samaj Party 3 . CPI Communist Party of India 4 . CPM Communist Party of India (Marxist) 5 . INC Indian National Congress 6 . NCP Nationalist Congress Party STATE PARTIES 7 . AC Arunachal Congress 8 . ADMK All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam 9 . AGP Asom Gana Parishad 10 . AIFB All India Forward Bloc 11 . AITC All India Trinamool Congress 12 . BJD Biju Janata Dal 13 . CPI(ML)(L) Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) (Liberation) 14 . DMK Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam 15 . FPM Federal Party of Manipur 16 . INLD Indian National Lok Dal 17 . JD(S) Janata Dal (Secular) 18 . JD(U) Janata Dal (United) 19 . JKN Jammu & Kashmir National Conference 20 . JKNPP Jammu & Kashmir National Panthers Party 21 . JKPDP Jammu & Kashmir Peoples Democratic Party 22 . JMM Jharkhand Mukti Morcha 23 . KEC Kerala Congress 24 . KEC(M) Kerala Congress (M) 25 . MAG Maharashtrawadi Gomantak 26 . MDMK Marumalarchi Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam 27 . MNF Mizo National Front 28 . MPP Manipur People's Party 29 . MUL Muslim League Kerala State Committee 30 . -

Shri Vinay Kumar Sorake Called the Attention of the Minister Of

nt> 12.10 hrs. Title: Shri Vinay Kumar Sorake called the attention of the Minister of Environemnt and Forests regarding drive to dispossess land-holdings of poor and tribal people settled in forest areas of Karnataka. SHRI VINAY KUMAR SORAKE (UDUPI): Sir, I call the attention of the Minister of Environment and Forest to the following matter of urgent public importance and request that he may make a statement thereon "The situation arising out of drive to dispossess the land holdings of the poor and the tribal people settled in forest areas of Karnataka and the steps taken by the Government in regard thereto." THE MINISTER OF ENVIRONMENT AND FORESTS (SHRI T.R. BAALU): Sir, at the outset, I would like to bring to the kind attention of this august House about the healthy tradition of living in harmony with nature, that is inherent part of our culture. The close relationship between the long-term survival of mankind specially the tribals and maintenance of natural forests has always been appreciated by our society. However, after Independence, the pressure of development led to massive diversion of forest lands for various non-forestry purposes, including agriculture. Encroachment of forest land for cultivation and other purposes, which is an offence under the Indian Forest Act, 1927, continues to be the most pernicious practice endangering forest resources throughout the country. Information compiled by the Ministry of Agriculture during early 1980s revealed that nearly seven lakh hectares of forest land was under encroachment in the country about a decade back. This is despite the fact that prior to 1980, a number of States had regularised such encroachments periodically and approximately 43 lakh hectares of forest land was diverted for various purposes between 1951 and 1980, more than half of it is for agricultural purposes. -

NDTV Pre Poll Survey - U.P

AC PS RES CSDS - NDTV Pre poll Survey - U.P. Assembly Elections - 2002 Centre for the Study of Devloping Societies, 29 Rajpur Road, Delhi - 110054 Ph. 3951190,3971151, 3942199, Fax : 3943450 Interviewers Introduction: I have come from Delhi- from an educational institution called the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (give your university’s reference). We are studying the Lok Sabha elections and are interviewing thousands of voters from different parts of the country. The findings of these interviews will be used to write in books and newspapers without giving any respondent’s name. It has no connection with any political party or the government. I need your co-operation to ensure the success of our study. Kindly spare some ime to answer my questions. INTERVIEW BEGINS Q1. Have you heard that assembly elections in U.P. is to be held in the next month? 2 Yes 1 No 8 Can’t say/D.K. Q2. Have you made up your mind as to whom you will vote during the forth coming elections or not? 2 Yes 1 No 8 Can’t say/D.K. Q3. If elections are held tomorrow it self then to whom will cast your vote? Please put a mark on this slip and drop it into this box. (Supply the yellow dummy ballot, record its number & explain the procedure). ________________________________________ Q4. Now I will ask you about he 1999 Lok Sabha elections. Were you able to cast your vote or not? 2 Yes 1 No 8 Can’t say/D.K. 9 Not a voter. -

India: the Weakening of the Congress Stranglehold and the Productivity Shift in India

ASARC Working Paper 2009/06 India: The Weakening of the Congress Stranglehold and the Productivity Shift in India Desh Gupta, University of Canberra Abstract This paper explains the complex of factors in the weakening of the Congress Party from the height of its power at the centre in 1984. They are connected with the rise of state and regional-based parties, the greater acceptability of BJP as an alternative in some of the states and at the Centre, and as a partner to some of the state-based parties, which are in competition with Congress. In addition, it demonstrates that even as the dominance of Congress has diminished, there have been substantial improvements in the economic performance and primary education enrolment. It is argued that V.P. Singh played an important role both in the diminishing of the Congress Party and in India’s improved economic performance. Competition between BJP and Congress has led to increased focus on improved governance. Congress improved its position in the 2009 Parliamentary elections and the reasons for this are briefly covered. But this does not guarantee an improved performance in the future. Whatever the outcomes of the future elections, India’s reforms are likely to continue and India’s economic future remains bright. Increased political contestability has increased focus on governance by Congress, BJP and even state-based and regional parties. This should ensure improved economic and outcomes and implementation of policies. JEL Classifications: O5, N4, M2, H6 Keywords: Indian Elections, Congress Party's Performance, Governance, Nutrition, Economic Efficiency, Productivity, Economic Reforms, Fiscal Consolidation Contact: [email protected] 1. -

List of Hon'ble Member of Parliament (Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha) Serving NWR Jurisdiction As on 26.08.2019

List of Hon'ble Member of Parliament (Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha) serving NWR Jurisdiction As on 26.08.2019 Sr. Name LS/RS/ Party Delhi Address Permanent Address Contact No. Email & No. Constituency Name Remarks AJMER DIVISION 1 Sh. Arjunlal Meena LS/Udaipur BJP 212, North Avenue, 6A-34, Paneriyo Ki Madri, Tel : (0294) 2481230, [email protected] New Delhi- Sector-9, Housing Board 09414161766 (M) n 11000109013869355 Colony, Udaipur-313001, Fax : (0294) 2486100 (M) Rajasthan 2 Sh. Chandra Prakash LS/Chittorgarh BJP 13-E, Ferozshah Road, 61, Somnagar-II, Madhuban Telefax : (01472) [email protected] Joshi New Delhi-110 001 Senthi, Chittourgarh, 243371, 09414111371 Rajasthan-312001 (M) (011) 23782722, 09868113322 (M) 3 Sh. Dipsinh LS/Sabarkantha BJP A-6, MS Flats, B.K.S. Darbar Mahollo (Bhagpur), Tel : (02770) 246322, dipsinghrathord62@gmail Shankarsinh Rathod Marg, Vaghpur, 09426013661(M) .com Near Dr. R.M.L. Sabarkantha-383205, Fax : (02772) 245522 Hospital, New Delhi- Gujarat 110001 4 Shri Parbhatbhai LS/ BJP 1, Gayatri Society, Highway Tel. (02939) 222021, Savabhai Patel Banaskantha Char Rasta, Tharad, At. P.O. 09978405318 (M) (Gujarat) & Teh. Tharad, Distt. Banaskantha, Gujarat 5 Sh. Kanakmal LS/ Banswara BJP Vill. Falated, P/O. 09414104796 (M) kanakmalkatara20@gmail Katara (ST) Bhiluda,Tehsil, Sagwara .com (Rajasthan) Distt. Dungarpur, Rajasthan 6 Sh. Bhagirath LS / Ajmer BJP Choyal House, Shantinagar, 9414011998 (M) Bhagirathchoudhary.25@ Chaudhary (Rajasthan) Madanganj, Kishangarh gmail.com Distt. Ajmer - 305801, Rajasthan 7 Smt. Diya Kumari LS/ Rajsamand BJP 944, City Palace, Near, Tel : (0141) 4088888, [email protected] Jantar Mantar 4088933 m Distt. Jaipur, Rajasthan – 09829050077 (M) 302002 8 Sh. -

Modi, Social Media, and Competitive Electoral Populism in India

International Journal of Communication 11(2017), 4158–4180 1932–8036/20170005 Fragile Hegemony: Modi, Social Media, and Competitive Electoral Populism in India SUBIR SINHA1 School of Oriental and African Studies, London, UK Direct and unmediated communication between the leader and the people defines and constitutes populism. I examine how social media, and communicative practices typical to it, function as sites and modes for constituting competing models of the leader, the people, and their relationship in contemporary Indian politics. Social media was mobilized for creating a parliamentary majority for Narendra Modi, who dominated this terrain and whose campaign mastered the use of different platforms to access and enroll diverse social groups into a winning coalition behind his claims to a “developmental sovereignty” ratified by “the people.” Following his victory, other parties and political formations have established substantial presence on these platforms. I examine emerging strategies of using social media to criticize and satirize Modi and offering alternative leader-people relations, thus democratizing social media. Practices of critique and its dissemination suggest the outlines of possible “counterpeople” available for enrollment in populism’s future forms. I conclude with remarks about the connection between activated citizens on social media and the fragility of hegemony in the domain of politics more generally. Keywords: Modi, populism, Twitter, WhatsApp, social media On January 24, 2017, India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), proudly tweeted that Narendra Modi, its iconic prime minister of India, had become “the world’s most followed leader on social media” (see Figure 1). Modi’s management of—and dominance over—media and social media was a key factor contributing to his convincing win in the 2014 general election, when he led his party to a parliamentary majority, winning 31% of the votes cast. -

'Ambedkar's Constitution': a Radical Phenomenon in Anti-Caste

Article CASTE: A Global Journal on Social Exclusion Vol. 2 No. 1 pp. 109–131 brandeis.edu/j-caste April 2021 ISSN 2639-4928 DOI: 10.26812/caste.v2i1.282 ‘Ambedkar’s Constitution’: A Radical Phenomenon in Anti-Caste Discourse? Anurag Bhaskar1 Abstract During the last few decades, India has witnessed two interesting phenomena. First, the Indian Constitution has started to be known as ‘Ambedkar’s Constitution’ in popular discourse. Second, the Dalits have been celebrating the Constitution. These two phenomena and the connection between them have been understudied in the anti-caste discourse. However, there are two generalised views on these aspects. One view is that Dalits practice a politics of restraint, and therefore show allegiance to the Constitution which was drafted by the Ambedkar-led Drafting Committee. The other view criticises the constitutional culture of Dalits and invokes Ambedkar’s rhetorical quote of burning the Constitution. This article critiques both these approaches and argues that none of these fully explores and reflects the phenomenon of constitutionalism by Dalits as an anti-caste social justice agenda. It studies the potential of the Indian Constitution and responds to the claim of Ambedkar burning the Constitution. I argue that Dalits showing ownership to the Constitution is directly linked to the anti-caste movement. I further argue that the popular appeal of the Constitution has been used by Dalits to revive Ambedkar’s legacy, reclaim their space and dignity in society, and mobilise radically against the backlash of the so-called upper castes. Keywords Ambedkar, Constitution, anti-caste movement, constitutionalism, Dalit Introduction Dr. -

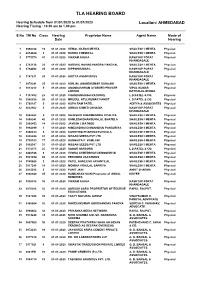

Tla Hearing Board

TLA HEARING BOARD Hearing Schedule from 01/01/2020 to 01/01/2020 Location: AHMEDABAD Hearing Timing : 10.30 am to 1.00 pm S.No TM No Class Hearing Proprietor Name Agent Name Mode of Date Hearing 1 3958238 19 01-01-2020 HEMAL NILESH MEHTA SHAILESH I MEHTA Physical 2 4014884 3 01-01-2020 RUDRA CHEMICAL SHAILESH I MEHTA Physical 3 3775574 41 01-01-2020 VIKRAM AHUJA KASHYAP POPAT Physical KHANDAGALE 4 3743128 25 01-01-2020 HARSHIL NAVINCHANDRA PANCHAL SHAILESH I MEHTAPhysical 5 3794452 25 01-01-2020 DIPESHKUMAR L KASHYAP POPAT Physical KHANDAGALE 6 3767211 20 01-01-2020 ADITYA ASSOCIATES KASHYAP POPAT Physical KHANDAGALE 7 3979241 25 01-01-2020 KUNJAL ANANDKUMAR DUNGANI SHAILESH I MEHTA Physical 8 3813212 5 01-01-2020 ANANDASHRAM AYURVED PRIVATE VIPUL KUMAR Physical LIMITED DAYHALAL BHEDA 9 3197802 25 01-01-2020 CHANDANSINGH RATHORE L.D.PATEL & CO. Physical 10 3980535 30 01-01-2020 MRUDUL ATULKUMAR PANDIT L.D.PATEL & CO. Physical 11 3760197 5 01-01-2020 KUPA RAM PATEL. ADITYA & ASSOCIATES Physical 12 3632502 5 01-01-2020 ABBAS AHMED UCHADIA KASHYAP POPAT Physical KHANDAGALE 13 3802482 5 01-01-2020 RAJESHRI DHARMENDRA PIPALIYA SHAILESH I MEHTAPhysical 14 3958241 42 01-01-2020 KAMLESH DHANSUKHLAL BHATELA SHAILESH I MEHTAPhysical 15 3966453 14 01-01-2020 JAYESH L RATHOD SHAILESH I MEHTA Physical 16 3992099 1 01-01-2020 NIMESHBHAI CHIMANBHAI PANSURIYA SHAILESH I MEHTA Physical 17 4008824 5 01-01-2020 CARRYING PHARMACEUTICALS SHAILESH I MEHTA Physical 18 3992098 31 01-01-2020 NISSAN SEEDS PVT LTD SHAILESH I MEHTA Physical 19 3738100 17 01-01-2020 KANHAIYA P. -

The Political Historiography of Modern Gujarat

The Political Historiography of Modern Gujarat Tannen Neil Lincoln ISBN 978-81-7791-236-4 © 2016, Copyright Reserved The Institute for Social and Economic Change, Bangalore Institute for Social and Economic Change (ISEC) is engaged in interdisciplinary research in analytical and applied areas of the social sciences, encompassing diverse aspects of development. ISEC works with central, state and local governments as well as international agencies by undertaking systematic studies of resource potential, identifying factors influencing growth and examining measures for reducing poverty. The thrust areas of research include state and local economic policies, issues relating to sociological and demographic transition, environmental issues and fiscal, administrative and political decentralization and governance. It pursues fruitful contacts with other institutions and scholars devoted to social science research through collaborative research programmes, seminars, etc. The Working Paper Series provides an opportunity for ISEC faculty, visiting fellows and PhD scholars to discuss their ideas and research work before publication and to get feedback from their peer group. Papers selected for publication in the series present empirical analyses and generally deal with wider issues of public policy at a sectoral, regional or national level. These working papers undergo review but typically do not present final research results, and constitute works in progress. Working Paper Series Editor: Marchang Reimeingam THE POLITICAL HISTORIOGRAPHY OF MODERN -

11-00 Am 1. Starred Qu

RAJYA SABHA FRIDAY, THE 11TH JULY, 2014 (The Rajya Sabha met in the Parliament House at 11-00 a.m.) 11-00 a.m. 1. Starred Questions The following Starred Questions were orally answered:- Starred Question No. 61 regarding Pending railway project proposals. Starred Question No. 62 regarding Security mechanism in Railways. Starred Question No. 63 regarding Performance of BSNL and MTNL. @11-33 a.m. (The House adjourned at 11-33 a.m. and re-assembled at 11-42 a.m.) Starred Question No.64 regarding Collision of Gorakhdham Express with goods train. Starred Question No.65 regarding Status of railway lines/tracks and stations. Starred Question No.66 regarding Increase in passenger fares and freight charges. Answers to remaining Starred Question Nos.67 to 80 were laid on the Table. 2. Unstarred Questions Answers to Unstarred Question Nos. 386 to 511 were laid on the Table. 12-00 Noon. 3. Ruling by the Chair The Chairman gave the following ruling:— ―Hon’ble Members on July 9, I received some notices of alleged Breach of Privilege on account of leakage of certain portions of the Railway Budget (2014-2015) in a newspaper on July 8, 2014, the day on which it was laid in this House. The notices were from Shri Madhusudan Mistry, Shri V. Hanumantha Rao, Shri Shantaram Naik, Smt. Rajani Patil, Shri Praveen Rashtrapal and Shri Ashk Ali Tak, members, Rajya Sabha. They enclosed a clipping of the Indian Express of July 8, 2014 which contained certain proposals of the Government which were to be announced during the Railway Minister’s budget speech. -

Government of India Ministry of Home Affairs Rajya Sabha

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS RAJYA SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 788 TO BE ANSWERED ON THE 16th JULY, 2014 / ASHADHA 25, 1936 (SAKA) COMMUNAL RIOTS IN THE COUNTRY 788. SHRI MADHUSUDAN MISTRY: Will the Minister of HOME AFFAIRS be pleased to state: (a) the number of communal riots which occurred after 1st May 2014, State-wise; (b) the number of people killed and the number of people injured; (c) whether Government intends to bring the law to prevent communal riots; (d) the measures taken to prevent the recurrence of such communal riots; and (e) whether victims were paid compensation and if so, the amount of compensation? ANSWER MINISTER OF STATE IN THE MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (SHRI KIREN RIJIJU) (a)to(b) As per available information, the State-wise details of communal riots occurred during 1st May 2014 to 30th June, 2014, persons killed and injured therein are enclosed as Annexure. (c)to(e) “Police” and “Public Order” are State subjects under the Constitution of India. The responsibility of dealing with communal violence as per the provisions of extant laws and maintaining relevant data in this regard rests primarily with respective State Governments. Details like compensation paid to the affected families by the State Governments are not maintained centrally. .....2/- -: 2 :- RSUSQ NO. 788 FOR 16.07.2014 To maintain communal harmony in the country, the Central Government assists the State Governments/ Union Territory Administrations in a variety of ways like sharing of intelligence, sending alert messages, sending Central Armed Police Forces, including the composite Rapid Action Force created specially to deal with communal situations, to the concerned State Governments on specific requests and in the modernization of the State Police Forces. -

Acct Nm Address City Pin Code

ACCT NM ADDRESS CITY PIN CODE RAMESHCHANDRA BHAGVANJIBHAI RATHOD VIRANI MENSION,, 54, DIGVIJAY PLOT,, JAMNAGAR JAMNAGAR 361005 MAHENDRA SHANTILAL MANIYAR RANJIT NAGAR,, BLOCK NO.G/8, ROOM NO.2097, JAMNAGAR JAMNAGAR 361005 PUNAMCHAND NEMCHAND SHAH 42/43,DIGVIJAY PLOT,, NEAR JAIN UPASHRAYA,, JAMNAGAR JAMNAGAR 361005 ANANTRAI CHHABILDAS MAHTA ANDABAVA NO CHAKLOW,, BEHIND TALIKA SCHOOL, DHOBI'S DELI,, JAMNAGAR JAMNAGAR 361001 VINODKUMAR KALYANJIBHAI VASANT [KILUBHAI] K V ROAD,, POTRY STREET,, JAMNAGAR JAMNAGAR NAVINCHANDRA MULJI SHAH 14-SHNEHDHARA APPARTMENT, 6-PATEL COLONY, JAMNAGAR JAMNAGAR CHUNILAL TRIBHOVAN BUDH 55DIGVIJAY PLOT,, VIRPARBHAI'S HOUSE,, JAMNAGAR JAMNAGAR 361005 HASMUKH HEMRAJ SHAH [HUF] 9,JAY CO-OP SOCIETY, AERODROME ROAD, JAMNAGAR JAMNAGAR RAJESH RATILAL VISHROLIYA NEW ARAM COLONY,, NEAR JAY CORP., JAMNAGAR JAMNAGAR 361005 BHARAT PARSHOTTAM VED GULAB BAUG,, ARYA SAMAAJ ROAD,, JAMNAGAR JAMNAGAR RAJIV MANILAL SHAH NEAR MORAR BAG,, OPP. LAL BAG, CHANDI BAZAAR,, JAMNAGAR JAMNAGAR 361001 VINODCHANDRA JAGJIVAN SHAH JAYRAJ, OPP-GURUDATATRAY TEMPAL PALACE ROAD, JAMNAGAR JAMNAGAR MINA JAYESH MEHTA [STAFF] JAMNAGAR, , JAMNAGAR JAMNAGAR RAJENDRA BABULAL ZAVERI 504 SHALIBHADRA APTT, PANCHESWAR TOWER ROAD, JAMNAGAR JAMNAGAR JYOTIBEN JAGDISHKUMAR JOISAR 4 TH FLOOR,, MILAN APARTMENT, MIG COLONY,, JAMNAGAR JAMNAGAR 361005 VIRENDRA OMPRAKASH ZAWAR 23/1/A RAJNAGAR, NR. ANMOL APPARTMENT, SARU SECTION ROAD JAMNAGAR 361006 MAHENDRA HEMRAJ SHAH (H.U.F) C/O VELJI SURA SHAH, 4 OSWAL COLONY SUMMAIR CLUB ROAD, JAMNAGAR JAMNAGAR 361005 MAHESH BHOVANBHAI DOBARIYA 'TARUN',, SARDAR PATEL NAGAR, B/H.JOLLY BUNGALOW,, JAMNAGAR JAMNAGAR HIMATLAL LAKHAMSI SHAH C/O. R. C. LODAYA AND CO., PANCHESWAR TOWER ROAD,, JAMNAGAR JAMNAGAR 361001 MUKTABEN GORDHANDAS KATARIA 8-A PARAS SOCIETY, , JAMNAGAR JAMNAGAR 361001 AMRUTBEN TARACHAND SHAH 53, DIGVIJAY PLOT, , JAMNAGAR JAMNAGAR DHANJI TAPUBHAI AJANI GEL KRUPA, OPP KOLI BUILDING, 3 KRUSHNANAGARKHODIYAR COLONY JAMNAGAR 361006 HITENDRA RAMNIKLAL HARKHANI 3,GOKULDHAM APPARTMENT,, K.P.