Vod.Pdf (PDF File, 504.7

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2007 Creating and Distributing Top-Quality News, Sports and Entertainment Around the World

Annual Report 2007 Creating and distributing top-quality news, sports and entertainment around the world. News Corporation As of June 30, 2007 Filmed Entertainment WJBK Detroit, MI Latin America United States KRIV Houston, TX Cine Canal 33% Fox Filmed Entertainment KTXH Houston, TX Telecine 13% Twentieth Century Fox Film KMSP Minneapolis, MN Australia and New Zealand Corporation WFTC Minneapolis, MN Premium Movie Partnership 20% Fox 2000 Pictures WTVT Tampa Bay, FL Fox Searchlight Pictures KSAZ Phoenix, AZ Cable Network Programming Fox Atomic KUTP Phoenix, AZ United States Fox Music WJW Cleveland, OH FOX News Channel Twentieth Century Fox Home KDVR Denver, CO Fox Cable Networks Entertainment WRBW Orlando, FL FX Twentieth Century Fox Licensing WOFL Orlando, FL Fox Movie Channel and Merchandising KTVI St. Louis, MO Fox Regional Sports Networks Blue Sky Studios WDAF Kansas City, MO (15 owned and operated) (a) Twentieth Century Fox Television WITI Milwaukee, WI Fox Soccer Channel Fox Television Studios KSTU Salt Lake City, UT SPEED Twentieth Television WBRC Birmingham, AL FSN Regency Television 50% WHBQ Memphis, TN Fox Reality Asia WGHP Greensboro, NC Fox College Sports Balaji Telefilms 26% KTBC Austin, TX Fox International Channels Latin America WUTB Baltimore, MD Big Ten Network 49% Canal Fox WOGX Gainesville, FL Fox Sports Net Bay Area 40% Asia Fox Pan American Sports 38% Television STAR National Geographic Channel – United States STAR PLUS International 75% FOX Broadcasting Company STAR ONE National Geographic Channel – MyNetworkTV STAR -

Life Begins After 30 the Range Rover Classic

Life Begins After 30 The Range Rover Classic By Jeffrey B. Aronson Age slips up to most of us, and the next thing you know, you’re a “classic.” It may be hard to believe, but the Range Rover has now delighted automotive enthusiasts since its unveiling 31 years ago. When Land Rover afficionados discuss “old Land Rovers,” they must now include Range Rovers, too. The Range Rover has been with us in much the same manner for three decades; even the “new” model in 1994 retained many of the engineering cues of the original. The original Range Rover, dubbed the “Classic,” took the Land Rover concept of “crossover vehicle” and made it more sophisticated. Whereas the Land Rover made itself into a station wagon by adding more seats to a utility vehicle, it First didn’t fool passengers one bit. The Range Rover Impressions combined luxury, performance, station wagon utility, and of course, off road capability, in a car that asked little compromise from its owners. Look at a photo of the Range Rover, the two- American 4 x 4’s included International Bruce McWilliams, reported he was white-knuckled door of its first decade. Marvel at the high green- Harvester Scouts, square utility vehicles with seats driving one. house, the castle corners of the hood line, the clever that rusted on contact with humidity. Ford Broncos Indeed, so few Americans desiring a station blackout of the rear pillars, the bold, rectangular resembled telephone booths and came with 3- wagon were captivated by the poky 109” with the creases in the flanks. -

Idea Lab Session: Smartphone Tips & Tools for Success

Idea Lab Session: SmartPhone Tips & Tools for Success Thursday, February 28, 2013, 8:30 and 11:10 a.m. Randall Dean, MBA Author and Trainer Randall Dean Consulting and Training, LLC East Lansing, Mich. Randall Dean, the "totally obsessed" time management/PDA guy and email sanity expert and author of the recent Amazon email bestseller, “Taming the E-mail Beast: 45 Key Strategies for Managing Your E-mail Overload,” is a preferred source for speaking and training programs on advanced time management-using technology, managing the mess of email and information overload, and related topics including managing great meetings and ending office clutter. Randy has more than 20 years of experience using and teaching advanced principles of time management, project management, and personal organization. His popular keynote/breakout programs, "Finding an Extra Hour Every Day" and "Taming the E-mail Beast: Managing the Mess of E-mail and Info Overload" are great sessions for conference and association meetings. These programs combine humor with extraordinarily relevant and useful content and provide strategy- rich information on finding and saving time and taming the email beast at home and work. Session Description: Get organized and maximize your efficiency by learning amazing smartphone tips and tools during this interactive session. Top Three Session Ideas Tools or tips you learned from this session and can apply back at the office. 1. ______________________________________________________________________ 2. _______________________________________________________________________ -

List of Participating Merchants Mastercard Automatic Billing Updater

List of Participating Merchants MasterCard Automatic Billing Updater 3801 Agoura Fitness 1835-180 MAIN STREET SUIT 247 Sports 5378 FAMILY FITNESS FREE 1870 AF Gilroy 2570 AF MAPLEWOOD SIMARD LIMITED 1881 AF Morgan Hill 2576 FITNESS PREMIER Mant (BISL) AUTO & GEN REC 190-Sovereign Society 2596 Fitness Premier Beec 794 FAMILY FITNESS N M 1931 AF Little Canada 2597 FITNESS PREMIER BOUR 5623 AF Purcellville 1935 POWERHOUSE FITNESS 2621 AF INDIANAPOLIS 1 BLOC LLC 195-Boom & Bust 2635 FAST FITNESS BOOTCAM 1&1 INTERNET INC 197-Strategic Investment 2697 Family Fitness Holla 1&1 Internet limited 1981 AF Stillwater 2700 Phoenix Performance 100K Portfolio 2 Buck TV 2706 AF POOLER GEORGIA 1106 NSFit Chico 2 Buck TV Internet 2707 AF WHITEMARSH ISLAND 121 LIMITED 2 Min Miracle 2709 AF 50 BERWICK BLVD 123 MONEY LIMITED 2009 Family Fitness Spart 2711 FAST FIT BOOTCAMP ED 123HJEMMESIDE APS 2010 Family Fitness Plain 2834 FITNESS PREMIER LOWE 125-Bonner & Partners Fam 2-10 HBW WARRANTY OF CALI 2864 ECLIPSE FITNESS 1288 SlimSpa Diet 2-10 HOLDCO, INC. 2865 Family Fitness Stand 141 The Open Gym 2-10 HOME BUYERS WARRRANT 2CHECKOUT.COM 142B kit merchant 21ST CENTURY INS&FINANCE 300-Oxford Club 147 AF Mendota 2348 AF Alexandria 3012 AF NICHOLASVILLE 1486 Push 2 Crossfit 2369 Olympus 365 3026 Family Fitness Alpin 1496 CKO KICKBOXING 2382 Sequence Fitness PCB 303-Wall Street Daily 1535 KFIT BOOTCAMP 2389730 ONTARIO INC 3045 AF GALLATIN 1539 Family Fitness Norto 2390 Family Fitness Apple 304-Money Map Press 1540 Family Fitness Plain 24 Assistance CAN/US 3171 AF -

FCC-11-4A1.Pdf

Federal Communications Commission FCC 11-4 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Applications of Comcast Corporation, ) MB Docket No. 10-56 General Electric Company ) and NBC Universal, Inc. ) ) For Consent to Assign Licenses and ) Transfer Control of Licensees ) ) MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER Adopted: January 18, 2011 Released: January 20, 2011 By the Commission: Chairman Genachowski and Commissioner Clyburn issuing separate statements, Commissioners McDowell and Baker concurring and issuing a joint statement, Commissioner Copps dissenting and issuing a statement. TABLE OF CONTENTS Heading Paragraph # I. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................. 1 II. DESCRIPTION OF THE PARTIES ...................................................................................................... 9 A. Comcast Corporation ....................................................................................................................... 9 B. General Electric Company............................................................................................................. 12 C. NBC Universal, Inc........................................................................................................................ 13 III. THE PROPOSED TRANSACTION.................................................................................................... 16 A. Description.................................................................................................................................... -

The Hollywood Cinema Industry's Coming of Digital Age: The

The Hollywood Cinema Industry’s Coming of Digital Age: the Digitisation of Visual Effects, 1977-1999 Volume I Rama Venkatasawmy BA (Hons) Murdoch This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Murdoch University 2010 I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. -------------------------------- Rama Venkatasawmy Abstract By 1902, Georges Méliès’s Le Voyage Dans La Lune had already articulated a pivotal function for visual effects or VFX in the cinema. It enabled the visual realisation of concepts and ideas that would otherwise have been, in practical and logistical terms, too risky, expensive or plain impossible to capture, re-present and reproduce on film according to so-called “conventional” motion-picture recording techniques and devices. Since then, VFX – in conjunction with their respective techno-visual means of re-production – have gradually become utterly indispensable to the array of practices, techniques and tools commonly used in filmmaking as such. For the Hollywood cinema industry, comprehensive VFX applications have not only motivated the expansion of commercial filmmaking praxis. They have also influenced the evolution of viewing pleasures and spectatorship experiences. Following the digitisation of their associated technologies, VFX have been responsible for multiplying the strategies of re-presentation and story-telling as well as extending the range of stories that can potentially be told on screen. By the same token, the visual standards of the Hollywood film’s production and exhibition have been growing in sophistication. -

General Motors Corporation, Hughes ) Electronics Corporation, and the ) News Corporation Limited ) MB Docket No

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, DC 20554 In the Matter of: ) ) General Motors Corporation, Hughes ) Electronics Corporation, And The ) News Corporation Limited ) MB Docket No. 03-124 Application To Transfer Control Of FCC ) Authorizations And Licenses Held By ) Hughes Electronics Corporation ) To The News Corporation Limited ) COMMENTS OF ADVANCE/NEWHOUSE COMMUNICATIONS, CABLE ONE, COX COMMUNICATIONS, AND INSIGHT COMMUNICATIONS Bruce D. Sokler Christopher J. Harvie Fernando Laguarda Robert G. Kidwell MINTZ, LEVIN, COHN, FERRIS, GLOVSKY AND POPEO, P.C. 701 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, 9th Floor Washington, DC 20004 (202) 434-7300 Bertram W. Carp WILLIAMS & JENSEN, P.C. 1155 – 21st Street, NW Washington, DC 20036 (202) 659-8201 Their Attorneys Dated: June 16, 2003 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY News Corp.’s proposed acquisition of DirecTV will amass an unprecedented combination of video programming content and distribution assets under a single corporate banner. The Commission has never before evaluated under the public interest standard the magnitude of vertical market issues presented by this transaction. Never before has a single company been armed with a national distribution platform, a national broadcast network, local TV stations in virtually every major media market, the governmentally- created retransmission consent power, and the “battering ram” of sports programming. Wielding this singularly potent array of content and distribution assets, News Corp. will have the ability and incentive to raise programming costs to consumers and damage competition in video programming distribution markets nationwide. News Corp.’s ability and incentive to raise prices will be particularly elevated in markets where it is dealing with smaller and medium-sized cable companies. The public interest benefits touted by the parties are insubstantial, especially in light of these likely harms. -

Stephen M. Cabrinety Collection in the History of Microcomputing, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt529018f2 No online items Guide to the Stephen M. Cabrinety Collection in the History of Microcomputing, ca. 1975-1995 Processed by Stephan Potchatek; machine-readable finding aid created by Steven Mandeville-Gamble Department of Special Collections Green Library Stanford University Libraries Stanford, CA 94305-6004 Phone: (650) 725-1022 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc © 2001 The Board of Trustees of Stanford University. All rights reserved. Special Collections M0997 1 Guide to the Stephen M. Cabrinety Collection in the History of Microcomputing, ca. 1975-1995 Collection number: M0997 Department of Special Collections and University Archives Stanford University Libraries Stanford, California Contact Information Department of Special Collections Green Library Stanford University Libraries Stanford, CA 94305-6004 Phone: (650) 725-1022 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Processed by: Stephan Potchatek Date Completed: 2000 Encoded by: Steven Mandeville-Gamble © 2001 The Board of Trustees of Stanford University. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Stephen M. Cabrinety Collection in the History of Microcomputing, Date (inclusive): ca. 1975-1995 Collection number: Special Collections M0997 Creator: Cabrinety, Stephen M. Extent: 815.5 linear ft. Repository: Stanford University. Libraries. Dept. of Special Collections and University Archives. Language: English. Access Access restricted; this collection is stored off-site in commercial storage from which material is not routinely paged. Access to the collection will remain restricted until such time as the collection can be moved to Stanford-owned facilities. Any exemption from this rule requires the written permission of the Head of Special Collections. -

1 N the Official Hamtramck City Business Directory N 2021 — City of Hamtramck —

1 n The Official Hamtramck City Business Directory n 2021 — City of Hamtramck — City Hall........................................................................(313) 800-5233 3401 Evaline Hrs. 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. General Admin General Number: ....................(313) 800-5233 Public Services: Water, Rubbish & Streets Ext 817 Building Department: Ext 296 Code Enforcement: Ext 3 28 Income Tax Dept: Ext 363 Assessor’s Office: Ext 820 Treasurer’s Office: Ext 822 Clerk’s Office: Ext 821 Human Resources Dept: Ext 348 City Manager’s Office: Ext 361 Community and Economic Development: Ext 316 Community Safety & Services: Ext 327 Police - General Number ....................(313) 800-5281 EMERGENCY 911 Dispatch Desk: Ext 501 Handicap Signs I.D. & Traffic: Ext 403 Narco Tip Line: Ext 317 Fire - General Number ....................(313) 305-4503 EMERGENCY 911 Fire Non-Emergency: Ext 221 Fire Marshal: Ext 225 Fire Chief: Ext 222 31st Court - General Number: ....................(313) 800-5248 Traffic/Criminal Clerks: Ext 812 Civil Clerk: Ext 280 Probation Officer: Ext 281 Library General Number: ....................(313) 733-6821 State of Michigan Secretary of State 9001 Joseph Campau ....................(313) 872-4396 Michigan Anti-Cruelty Society 13569 Joseph Campau ....................(313) 891-7188 U.S. Federal Government Social Security Administration 60 East Grand Ave., Highland Park, MI 48203 ..........(800) 772-1213 U.S. Post Office 2933 Caniff ....................(313) 891-7817 ur community, our nation, and the entire Oworld experienced a very difficult year in 2020. I feel confident, however, that in 2021 our nation and our region will get closer to getting the COVID-19 virus under control. This is thanks, in part, to an amazing vaccine and also to your efforts to follow state guidelines. -

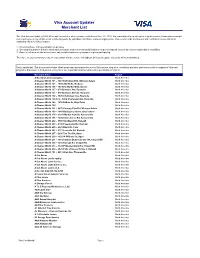

Visa Account Updater Merchant List

Visa Account Updater Merchant List The Visa Account Updater (VAU) Merchant List includes all merchants enrolled as of June 30, 2020. It is consolidated in an attempt to relay the most relevant and meaningful merchant name as merchants enroll at differing levels: by subsidiary, franchise, or parent organization. Visa recommends that issuers and merchants not use this list in marketing efforts for VAU because: 1. We do not have 100% penetration on all sides. 2. We cannot guarantee that the information exchange between the financial institution and merchant will occur in time for the cardholder’s next billing. 3. Some merchants on this list may have only certain divisions or geographic regions participating. Therefore, we do not want to create an expectation that the service will address all account update issues for all merchants listed. Visa Confidential: This document contains Visa's proprietary information for use by Visa issuers, acquirers, merchants and their processors solely in support of Visa card programs. Disclosure to third parties or any other use is prohibited without prior written permission of Visa Inc. Merchant Name Region A Buckley Landscaping Inc. North America A Cleaner World 106 – 3481 Robinhood Rd, Winston-Salem North America A Cleaner World 107 – 1009 2Nd St Ne, Hickory North America A Cleaner World 108 – 130 New Market Blvd, Boone North America A Cleaner World 127 – 679 Brandon Ave, Roanoke North America A Cleaner World 127 – 679 Brandon Avenue, Roanoke North America A Cleaner World 128 – 3806 Challenger Ave, Roanoke -

Tourism Worldwide Has Sparked the Best Hidden a Debate If Its Undoubted Benefits Are Now Beaches in Asia Outweighed by Less Quantifiable Downsides

PPS 1885/02/2017(025627) No. 1747/June 2017 Towards View from the top Growing an established brand like ITB should be easy, but Messe Berlin’s SVP travel & a tipping logistics, Martin Buck, never takes anything for granted. He tells Raini Hamdi why during ITB China’s successful debut point? + Booming tourism worldwide has sparked The best hidden a debate if its undoubted benefits are now beaches in Asia outweighed by less quantifiable downsides. Xinyi Liang-Pholsena takes stock of the Rising talents in dilemma and sees what needs to be done ASEAN tourism Cambodia’s staffing challenge June 2017 TTG Asia 2 Contents & editorial Want to read us on the go? Analysis 04 View from the top 08 On the radar 10 Shop 12 Connect 28 13 16 21 24 Report: Beach Destination: Destination: Destination: destinations Hong Kong Indonesia Cambodia When too much love can hurt ourism is such a wonderful industry. As a reporter afternoon in Georgetown, we were dismayed by the snak- Tworking in and writing about this industry, I have ing queue outside a particular stall. My uncle assured me had many first-hand opportunities to see how this in- the stall next door was just as good but saw fewer tourists dustry has shaped the lives of many around the world, because it wasn’t propelled to social media fame by blog- whether it’s improving livelihoods, preserving traditions gers and foreign websites. (True enough, he was back in or opening borders and minds alike. the car with eight packs of cendol minutes later.) What can we But if there’s one nagging thought, it’s that I’m one of While overcrowding is not yet a dire issue for Penang’s the 1.8 billion travelling masses who are complicit in en- tourism, the fear that visitors who once kept the local do to travel joying the spoils of tourism and stretching infrastructure traditions and livelihoods alive are also now slowly de- sustainably? to breaking point. -

The Moxy Page: 7

AUGUST 19, 2009 PAGE: 4 CONCIERGE CHRONICLES C H PAGE: 9 E S CHEF T Q&A E R PAGE: 18 C O SOUND U CHECK N T Y WWW.DAILYLOCAL.COM/CC C U IS IN E & N IG H T L IF E BEER AND BBQ PAGE: 22 OXY E M OT : 7 HE E N AGE T S TH P PLAY 0543715 xxx xxx /PAGE 3 TABLE AUG. 19, 2009 MAGA xxx ZINE CHESTER COUNTY CUISINE & NIGHTLIFE xx xxx OF www.dailylocal.com/CC xx STAFF: xxxCONTENTS Randall P. Notter Publisher Andrew M. Hachadorian Editor Justin McAneny PAGE: 4 Contributing Writer/Editorial Coordinator Concierge Chronicles Dixie Picnic Arlene McGranaghan Advertising Director CC is a magazine of the Daily Local News, published ev- ery other Wednesday and distributed free throughout Chester County. Our offi ces are located at 250 North Brad- PAGE: 5 ford Avenue, West Chester PA. Copyright 2009, Daily Lo- Buy Fresh Buy Local cal News. Reproduction of CC, in part or in whole, is pro- hibited without written permission. Pickle Me Pink PAGE: 9 Chef Q&A To advertise in CC, call Gastro-Pub Jim Steinbrecher at 610-430-1138. MARY’S MESSAGE: PAGE: 10 It’s the cold ice tea on the porch part of the summer and it Chester County is HOT. With the rising temps CC Cuisine and Nightlife is pleased to give you info and events to help cool you Road Trip down. Check out our Chester County Beer News, Top Foodie Movies for 2009 and all the entertainment and bands that you can handle in Chester County.