Strategies for Energy Efficiencies in Transportation (“SEET”)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

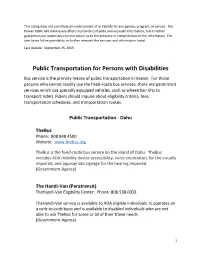

Public Transportation for Persons with Disabilities Bus Service Is the Primary Means of Public Transportation in Hawaii

This listing does not constitute an endorsement of or liability for any agency, program, or service. The Hawaii ADRC will make every effort to provide complete and accurate information, but it neither guarantees nor makes any representation as to the accuracy or completeness of the information. The user takes full responsibility to further research the services and information listed. Last Update: September 25, 2015 Public Transportation for Persons with Disabilities Bus service is the primary means of public transportation in Hawaii. For those persons who cannot readily use the fixed-route bus services, there are paratransit services which use specially equipped vehicles, such as wheelchair lifts to transport riders. Riders should inquire about eligibility criteria, fees, transportation schedules, and transportation routes. Public Transportation - Oahu TheBus Phone: 808.848.4500 Website: www.thebus.org TheBus is the fixed-route bus service on the island of Oahu. TheBus includes ADA mobility device accessibility, voice enunciators for the visually impaired, and appropriate signage for the hearing impaired. (Government Agency) The Handi-Van (Paratransit) TheHandi-Van Eligibility Center: Phone: 808.538.0033 TheHandi-Van service is available to ADA eligible individuals. It operates on a curb-to-curb basis and is available to disabled individuals who are not able to use TheBus for some or all of their travel needs. (Government Agency) 1 Travel Training using TheBus Phone: 808.538.0033 For older adults and persons with disabilities who meet TheHandi-Van eligibility criteria; travel training will show them how to use TheBus to get to their destination. This free program is tailored to the specific travel needs of each individual. -

State of Hawaii Strategic Plan for Transit-Oriented Development DRAFT

State of Hawaii Strategic Plan for Transit-Oriented Development Hawaii Interagency Council for Transit-Oriented Development Prepared Pursuant to Act 130, Session Laws of Hawaii 2016 by Office of Planning And Hawaii Housing Finance and Development Corporation Department of Business, Economic Development and Tourism State of Hawaii DRAFT October 2017 State Strategic Plan for Transit-Oriented/Transit-Ready Development—DRAFT PRINT DATE: 26-Oct-17 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 INTRODUCTION: A Framework for State Investments in Livable Communities ..................................... 1-1 1.1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Precedents to the TOD Council ........................................................................................................ 1-2 1.3 TOD Council Perspectives on TOD and TRD ..................................................................................... 1-4 1.4 A State Vision for TOD and Directed Growth ................................................................................... 1-4 1.5 Key Principles for State Investments in Livable Communities ......................................................... 1-5 1.6 Opportunities for TOD/TRD in Promoting Smart Growth and Livable Communities .................... 1-11 1.7 Purpose and Structure of the Plan ................................................................................................. 1-11 2 State TOD/TRD Implementation -

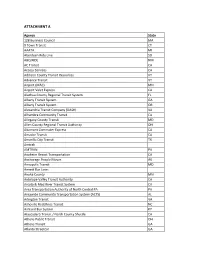

Attachment A

ATTACHMENT A Agency State 128 Business Council MA 9 Town Transit CT AAATA MI Aberdeen Ride Line SD ABQ RIDE NM AC Transit CA Access Services CA Addison County Transit Resources VT Advance Transit VT Airport (MAC) MN Airport Valet Express CA Alachua County Regional Transit System FL Albany Transit System GA Albany Transit System OR Alexandria Transit Company (DASH) VA Alhambra Community Transit CA Allegany County Transit MD Allen County Regional Transit Authority OH Altamont Commuter Express CA Amador Transit CA Amarillo City Transit TX Amtrak AMTRAN PA Anaheim Resort Transportation CA Anchorage People Mover AK Annapolis Transit MD Annett Bus Lines Anoka County MN Antelope Valley Transit Authority CA Arcata & Mad River Transit System CA Area Transportation Authority of North Central PA PA Areawide Community Transportation System (ACTS) AL Arlington Transit VA Asheville Redefines Transit NC Ashland Bus System KY Atascadero Transit / North County Shuttle CA Athens Public Transit OH Athens Transit GA Atlanta Streetcar GA Atlantic Station Shuttle GA Atomic City Transit NM Auburn Transit (Placer County Department of Public Works) CA Augusta Public Transit GA Avila Trolley CA Baker City Community Connection OR Banning Transit CA Barstow Area Transit CA Bart Bus WI Basin Transit Service OR Battle Creek Transit MI Bay Area Rapid Transit CA Bay Area Transportation Authority MI Bay Metro MI Bay State Cruise Company MA Bay Town Trolley FL Baylink CA BCTA (Beaver County Transit Authority) PA BE Line CA Beach Cities Transit - City of Redondo Beach (BCT) -

Kaua'i Short-Range Transit Plan

KAUA‘I SHORT-RANGE TRANSIT PLAN Final Report February 2018 Table of Contents Page Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................................................. ES-1 Why a Short-Range Transit Plan? ................................................................................................................................................................. ES-2 What Have We Heard From the Community? ........................................................................................................................................... ES-3 What Are the Key Themes?............................................................................................................................................................................ ES-5 How Do We Improve Transit on Kaua‘i? ..................................................................................................................................................... ES-7 What’s the Timeline? ...................................................................................................................................................................................... ES-24 1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................................... 1-1 How Is this Report Structured? ........................................................................................................................................................................ -

Multimodal Transportation Committee M I N U T

MULTIMODAL TRANSPORTATION COMMITTEE Council of the County of Maui M I N U T E S Council Chamber July 1, 2019 CONVENE: 9:01 a.m. PRESENT: VOTING MEMBERS: Councilmember Yuki Lei K. Sugimura, Chair Councilmember Riki Hokama, Vice-Chair Councilmember Tasha Kama Councilmember Kelly T. King (in at 9:04 a.m., out at 9:59 a.m.) Councilmember Alice L. Lee Councilmember Tamara Paltin Councilmember Shane M. Sinenci STAFF: James Krueger, Legislative Analyst John S. Rapacz, Legislative Attorney Stacey Vinoray, Committee Secretary Dawn Lono, Executive Assistant to Councilmember Shane Sinenci, Hana Council Office (via telephone conference bridge) Zhantell Lindo-Dudoit, Council Aide, Molokai Council Office (via telephone conference bridge) Don Atay, Executive Assistant to Councilmember Shane Sinenci ADMIN.: Michael J. Hopper, Deputy Corporation Counsel, Department of the Corporation Counsel Marc Takamori, Director, Department of Transportation Michael Du Pont, Deputy Director, Department of Transportation OTHERS: Seated in gallery: Paula Henry, Director of Operations, Roberts Hawaii Chris Kim, Manager of Operations (Maui), Roberts Hawaii Della Lampkin, General Manager (Maui), Roberts Hawaii Debbie Cabebe, Chief Executive Officer, Maui Economic Opportunity Harry Johnson, Transportation Director, Maui Economic Opportunity . Plus (4) others in the gallery PRESS: Akaku Maui Community Television, Inc. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - CHAIR SUGIMURA: . (gavel) . Good morning, everyone. Thank you for being here. Today is July 1st. Can you believe how fast this year is going by? It’s…I know. It’s 9:01 a.m. and we’re starting our Multimodal Transportation Committee meeting. Welcome, everyone. Please silence your noise-making devices. And my name is MULTIMODAL TRANSPORTATION COMMITTEE Council of the County of Maui July 1, 2019 Yuki Lei Sugimura, I’m the Chair of this Committee. -

Electrification of Transportation Strategic Roadmap

March 29, 2018 The Honorable Chair and Members of the Hawai 'i Public Utilities Commission ZOIB MAR 2CJ P 2: Li t; Kekuanaoa Building, 1st Floor PLJr' 1 iT'L 1··1·T--:c- 465 South King Street PU• ;.) ··' \,) j I ' .LJ ( ,. ('; ~ ....·' ~ l r:' :""· '·"' r- I I1 r'~~ I Honolulu, Hawai 'i 96813 . .. , I . , -..~· ..__) I ...... 1 Dear Commissioners: Subject: Docket No. 2016-0168 EV-F and EV-U Pilot Extension Electrification of Transportation Strategic Roadmap In accordance with Decision and Order Nci. 34592, 1 filed June 2, 2017 in the subject proceeding, the Hawaiian Electric Companies'2 respectfully submit their Electrification of Transportation ("EoT") Strategic Roadmap ("Roadmap"). The Roadmap represents a straightforward guide, based on input from stakeholders, transportation and technical experts, policymakers, non-government organizations and perhaps most importantly, customers, for turning the Companies' transportation transformation plans into actions. The Roadmap describes a number of steps to accelerate the EoT, including: (1) increasing electric vehicle ("EV") adoption by helping to lower costs and educating customers; (2) accelerating the buildout of EV charging infrastructure; (3) supporting the electrification of buses and other heavy equipment; (4) incentivizing EV charging to align with grid needs and save drivers and utility customers money; and (5) coordinating with ongoing grid modernization and planning efforts to help maximize the use of renewable resources. With these and other actions described in the Roadmap, the State can enhance its energy security and accelerate its transition from fossil fuels to renewable resources, both for the production of electricity and for ground transportation, while at the same time helping to facilitate more renewable resources online and helping to lower energy costs for customers. -

Newhawaii.Pdf

Portions of Voyaging Together to a New Life: A Handbook for Newcomers to Hawaii are from Raising Children in a New Country: An Illustrated Handbook © United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, Washington, D.C. 20017. These copyrighted portions are on pages 5, 13, 20, 21, 37, and 38 of Voyaging Together to a New Life: A Handbook for Newcomers to Hawaii. The information provided in this booklet is for general informational purposes only and may not be applicable to every situation. The information presented here is not intended to set any standards, nor is it to be taken as, nor should it replace, legal counsel. Although some of the information contained herein is about legal issues, this guide is not and should not be treated as legal advice. Due to the ever-changing nature of the law, the public should seek timely legal advice from counsel, based on current law. September 2008 This booklet may also be found on the Internet, at these sites: www.hawaiipirc.org/handbook www.nationsofmicronesia.org www.hawaii.gov/labor/ocs INTRODUCTION Hawaii is made up of a multitude of ethnic groups, all of whom have brought with them their own cultural diversity. Upon their arrival, they are embraced by the spirit of Aloha – a sense of welcome and understanding. In many Pacific Island cultures, the canoe is a symbol of strength, courage, teamwork, and perseverance. Like a canoe, newcomers must be ready for change and must be able to adjust to their surroundings by working together to overcome challenges. All cultures, all nations, and all people have one common value – respect for others. -

Statewide Mobility Management Report Report to the Twenty Eighth‐ Legislature ‐2015

Statewide Mobility Management Report Report to the Twenty Eighth‐ Legislature ‐2015 State of Hawai`i Department of Health Executive Office on Aging 250 S. Hotel Street, Suite 406 Honolulu, Hawai`i 96813 Table of Contents Page Acknowledgement………………………………………………………………………….. 2 Executive Summary………………………………………………………………………... 4 I. Introduction………………………………………………………………………………... 6 II. Methodology………………………………………………………………………………. 6 III. Definition of Mobility Management……………………………………………. 7 IV. Background and Status of County Transit Program……………………… 7 V. Proposed Framework of Mobility Management Program…………….. 19 i. Mobility Center …………………………………………………………………………….. 21 ii. Mobility Manager…………………………………………………………………………. 25 VI. Thinking Outside the Box………………………………………………………………. 26 VII. Financing a Mobility Program……………………………………………………….. 27 VIII. Recommendations……………………………………………………………………….. 29 Appendix A.…………………………………………………………………………………………. 30 Reference…..……………………………………………………………………………………..… 31 1 Acknowledgement The Executive Office on Aging extends its gratitude and mahalo to the Statewide Mobility Management Task Force, individuals and groups who contributed to this report. Statewide Task Force Members Wesley Lum, Executive Office on Aging (Chairperson) Nalani Aki, City and County of Honolulu Elderly Affairs Division Tom Brown, Hawai`i County Economic Opportunity Council, Inc. The Honorable Suzanne Chun‐Oakland, State Senate Merlita Compton, Kokua Kalihi Valley Comprehensive Health Center The Honorable Richard Creagan, State House of Representatives The -

Statewide and Maui & Kauai Regional Its Architecture

HAWAII STATEWIDE AND MAUI & KAUAI REGIONAL ITS ARCHITECTURE FINAL DOCUMENTATION APRIL 2017 Deliverable for: Hawaii Statewide ITS Architecture Hawaii Statewide and Maui & Kauai Regional ITS Architectures Final Documentation Version 1.1 Submitted to: Hawaii Department of Transportation Highways Division, Traffic Branch 601 Kamokila Boulevard, Kapolei, Hawaii 96707 Submitted by: ICx Transportation Group Makai Tower, Suite 1780 733 Bishop Street, Honolulu, Hawaii 96813 In association with: Consensus Systems Technologies, Corporation 301 East 87th Street, Ste. 7A New York, NY 10128 April 2017 Revision History Notes Rev. # Date Author QC (General Nature of Changes and Affected Pages) 1.0 1/31/17 B. EISENHART S. LOW Initial submittal to HDOT 1.1 4/13717 B. EISENHART S. LOW Address comments and finalize Table of Contents 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................1 1.1 The What and Why of ITS Architecture ...........................................................................1 1.2 Background ........................................................................................................................1 1.2.1 Goal #1: Implement an interagency incident management program ................................ 2 1.2.2 Goal #2: Provide advanced traveler information ............................................................. 2 1.2.3 Goal #3: Expand ITS state-wide .....................................................................................