APPENDIX January 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INDUSTRIAL ARCHAEOLGICAL SECTION of the DEVONSHIRE ASSOCIATION Issue 5 April 2019 CONTENTS

INDUSTRIAL ARCHAEOLGICAL SECTION of the DEVONSHIRE ASSOCIATION Issue 5 April 2019 CONTENTS DATES FOR YOUR DIARY – forthcoming events Page 2 THE HEALTH OF TAMAR VALLEY MINE WORKERS 4 A report on a talk given by Rick Stewart 50TH SWWERIA CONFERENCE 2019 5 A report on the event THE WHETSTONE INDUSTRY & BLACKBOROUGH GEOLOGY 7 A report on a field trip 19th CENTURY BRIDGES ON THE TORRIDGE 8 A report on a talk given by Prof. Bill Harvey & a visit to SS Freshspring PLANNING A FIELD TRIP AND HAVING A ‘JOLLY’ 10 Preparing a visit to Luxulyan Valley IASDA / SIAS VISIT TO LUXULYAN VALLEY & BEYOND 15 What’s been planned and booking details HOW TO CHECK FOR NEW ADDITIONS TO LOCAL ARCHIVES 18 An ‘Idiots Guide’ to accessing digitized archives MORE IMAGES OF RESCUING A DISUSED WATERWHEEL 20 And an extract of family history DATES FOR YOUR DIARY: Tinworking, Mining and Miners in Mary Tavy A Community Day Saturday 27th April 2019 Coronation Hall, Mary Tavy 10:00 am—5:00 pm Open to all, this day will explore the rich legacy of copper, lead and tin mining in the Mary Tavy parish area. Two talks, a walk, exhibitions, bookstalls and afternoon tea will provide excellent stimulation for discovery and discussion. The event will be free of charge but donations will be requested for morning tea and coffee, and afternoon cream tea will be available at £4.50 per head. Please indicate your attendance by emailing [email protected] – this will be most helpful for catering arrangements. Programme 10:00 Exhibitions, bookstalls etc. -

Fowey Parish

FOWEY PARISH DRAFT NEIGHBOURHOOD DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2019-2030 Contents 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 3 2 Fowey Parish NDP – The Preparation Process Getting this far ........................................................ 5 3 NDP Sustainability Appraisal ......................................................................................................... 6 4 Fowey NDP - Supporting Documentation....................................................................................... 6 5 Fowey NDP: The Vision ................................................................................................................. 7 6 Objectives of Fowey Parish NDP .................................................................................................... 9 7 Fowey Parish Housing Statement ................................................................................................ 10 8 Objective 1 General Development ............................................................................................... 12 Policy 1: Sustainable Development ........................................................................................... 12 Policy 2: Design and Character of Fowey Parish ....................................................................... 14 9 Objective 2: Housing ................................................................................................................... 16 Policy 3: Housing within -

SMP2 6 Final Report

6 ACTION PLAN 6.1 Coastal risk management activities The Action Plan for the Cornwall & Isles of Scilly Shoreline Management Plan review provides the basis for taking forward the intent of management which is discussed and developed through Chapter 4 - and summarised through the preferred policy choices set out in Chapter 5. The SMP guidance states that the purpose of the Action Plan is to summarise the actions that are required before the next review of the SMP however in reality the Action Plan is looking much further into the future in order to provide guidance on how the overall management intent for 100 years may be taken forward. For Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly SMP the Action Plan is a critical element, because there are various conditional policies for later epochs which need to be more firmly established in the future based on monitoring and investigation. The Action Plan can set the framework for an on-going shoreline management process in the coming years, with SMP3 in 5 to 10 years time as the next important milestone. This chapter therefore attempts to capture all intended actions necessary, on a policy unit by policy unit basis, to deliver the objectives at a local level. It should also help to prioritise FCRM medium and long-term planning budget lines. A number of the actions are representative of on-going commitments across the SMP area (for example to South West Regional Coastal Monitoring Programme). There are also actions that are representative of wide-scale intent of management, for example in relation to gaining a better understanding of the roles played by the various harbours and breakwaters located around the coast in terms of coast protection and sea defence. -

Below 2014.1

Quarterly Journal of the Shropshire Caving & Mining Club Spring Issue No: 2014.1 Sinkhole - the ‘IN’ word for 2014 The media seem to have discovered Caver Mark Noble provided the the word ‘Sinkhole’ this year, with photographs, but I think his wife almost every news report mentioning was taking a chance posing on the one opening up somewhere in collapsing edge in the one picture! Britain. While sinkholes are relatively rare in Broseley joined in with a hole The Broseley hole - covered with a Britain, they are regular occurrences opening up into old coal workings board. (Kelvin Lake - I.A.Recordings) in the USA where horror stories under the main road between However, this hole is small abound of people disappearing down Ironbridge and Broseley at compared to some of the holes holes while they sleep! Christmas. The Club’s Christmas that have been opening up in walk around Jackfield took a slight places such as Hemel Hempstead, The National Corvette Museum detour to view the hole - but it was Rickmansworth, Ripon and even in in Kentucky has been the latest cunningly hidden under a wooden the central reservation of the M2. victim. A sinkhole opened up inside panel. However we were assured that the museum on the 12th February it was much bigger underground, so All of these have occurred in chalk swallowing 8 vintage Corvettes - the road has been closed until the or gypsum areas and are probably including the historic 1 millionth Coal Authority can sort it out. natural solution holes caused by Corvette and rare cars on loan from General Motors. -

Appendix: Cornwall Annual Monitoring Report 2017

Appendix: Cornwall Annual Monitoring Report 2017 Supporting documents and analysis for the Cornwall Annual Monitoring Report 2017 Date: 14/12/2017 Version: 1 Cornwall Council CORNWALL MONITORING REPORT 2017 ‐ OVERVIEW TABLE No. INDICATOR TRENDS/TARGETS Reported? OVERALL JUDGEMENT NOTES 2.1 Number of new jobs created Provision of 38,000 full time jobs within the plan period. Current trends indicate a small shortfall 704,000 sqm of employment floorspace over the plan period (359,583 sqm to be B1a and B1b On track for industrial target but trailing for 2.2 Amount of net additional B Class employment floorspace provided office use, 344,417 sqm to be B1c, B2 and B8 industrial premises). Delivery in accordance with Office target sub area targets. Delivery of purpose built student accommodation that meets the needs generated through 2.3 Net additional purpose built student accommodation Projections indicate 58% PBSA by 2030 the expansion of the university in Falmouth and Penryn. Net additional Gypsy Traveller pitches provided by: (i) Residential Pitches; (ii) Transit Delivery of 318 residential pitches; 60 Transit pitches; and 11 Show People pitches in the plan 2.4 Currently behind on residential target. Pitches; (iii) Showpeople period. Delivery of 2,550 bed spaces in communal establishments (defined as Residential Care and or ® Under review as alternative provision is 2.5 Net additional communal nursing and specialist accommodation for older persons Nursing Homes). becoming favoured. Housing Trajectory including: To deliver a minimum -

St Austell, St Blazey and China Clay Area Schedule

This schedule contains the infrastructure requirements for 3 CNAs combined: the China Clay CNA, the St Austell CNA and the St Blazey, Fowey and Lostwithiel CNA. These three CNAs are taken together as a result of the combined planning framework for the area as set out in the St Austell, St Blazey and China Clay area Regeneration Plan and as reflected in the Core Strategy. Core Strategy Council priority: St Austell and the China Clay Eco Communities is one of the council’s two priority areas for regeneration. The China Clay area received national endorsement as the location for an eco ‘town’ (eco communities), forming part of a Government supported project to create a number of eco ‘towns’ communities creating outstanding places to live and work that meet high environmental and social standards. Core Strategy The Core Strategy identifies the area as a key transformational area and sets the strategic framework for transformational developments in the area. The Core Strategy seeks developments that address local needs to achieve high social standards, lead the way in achieving high quality, high environmental performance and to support the development of environmental technologies and industries. The Core Strategy key objectives for the China Clay; St Austell; St Blazey, Fowey & Lostwithiel CNAs: 1,500 homes in St Austell Elsewhere in the St Austell CNA 250 homes to support sustainable development of established communities 800 homes to the China Clay villages (collectively). 800 homes to St Blazey, Fowey & Lostwithiel CNA, distributed between the main settlements 5,000 homes in the three CNAs through transformational regeneration projects. -

Planning Future Cornwall

Cornwall Local Development Framework Framweyth Omblegya Teythyek Kernow Planning Future Cornwall Growth Factors: St Blazey, Fowey & Lostwithiel Network Area Version 2 February 2013 Growth Factors – St Blazey, Fowey & Lostwithiel Community Network Area This ‘Profile’ brings together a range of key facts about the St Blazey, Fowey & Lostwithiel Community Network Area that will act as an evidence base to help determine how much growth the area should accommodate over the next twenty years to maintain to enhance its viability and resilience. Please note that the strategic growth for the settlement of St Blazey/Par has been incorporated in the growth factors analysis for St Austell as they have been explored together as part of the preparation of the regeneration plan. Each ‘Profile’ is split into three sections: Policy Objectives, Infrastructure & Environmental Considerations and Socio-Economic Considerations. Summaries have been provided to indicate what the key facts might mean in terms of the need for growth – and symbols have been used as follows to give a quick overview: Supports the case for future No conclusion reached/ Suggests concern over growth neutral factor/further future growth evidence required St Blazey, Fowey & Lostwithiel Overview: The St Blazey, Fowey & Lostwithiel Community Network Area contains 11 parishes and a range of settlements. St Blazey/Par, Fowey and Lostwithiel are the key settlements within this area, and acts as the local service centres to the smaller settlements surrounding them. Larger villages in the area include Tywardreath and Luxulyan. Most of the CNA is an area of 'conservative' farming landscapes, dominated by anciently enclosed land, medieval field systems, scattered settlements with just a few larger villages, and several large, old-established estates with houses and parks (Boconnoc, Menabilly, and Lanhydrock) 1. -

PDZ3 1 February 2011

PDZ: 3 Gribbin Head to Black Head Management Area 06 Management Area 07 Gribbin Head Gribbin Head to Black Head This section of coastline encompasses St Austell Bay and includes the communities of Polkerris, Par, Carlyon Bay, Charlestown, Duporth and Porthpean as well as open countryside, tourist amenities and agricultural land. The bay faces south and is a rocky embayment that is relatively protected and rich in sediment with Par Sands and Carlyon Bay relatively large sandy beaches. Cornwall and Isles of Scilly SMP2 Final Report Chapter 4 PDZ3 1 February 2011 Cornwall and Isles of Scilly SMP2 Final Report Chapter 4 PDZ3 2 February 2011 General Description Built Environment Carlyon Bay There are a number of fixed assets at the coast, particularly related to the major dock and harbour infrastructure at Par and the communities at Carlyon Bay, Charlestown and Duporth. There is also a harbour wall and quayside at Polkerris. There are significant works on Crinnis Beach at Carlyon Bay (see photo opposite), relating to proposed development of Crinnis and Shorthorn beaches above the current mean high water position, on the site of the now derelict Cornwall Coliseum. Heritage Charlestown Harbour Historic features are present with four Scheduled Monuments in the area including a Bronze Age barrow close to Gribbin Head, and an Iron Age fort at Black Head. Also present are numerous barrows, and Par and Charlestown (photo, right) are historic china clay ports.There are also Historic Parks and Gardens at Tregrehan and a number of Conservation Areas present including Charlestown and Polkerris. Charlestown Harbour is included within the Cornwall and West Devon World Heritage Site designation. -

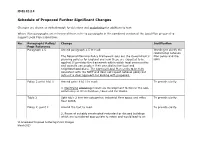

ID.01.CC.2.4 Schedule of Proposed Further Significant Changes

ID.01.CC.2.4 Schedule of Proposed Further Significant Changes Changes are shown as strikethrough for deletions and underlining for additions to text Where Plan paragraphs are referenced these refer to paragraphs in the combined version of the Local Plan prepared to support Local Plan submission. No. Paragraph/ Policy/ Change Justification Page Reference Paragraph 1.5 Amend paragraph 1.5 to read: Wording to clarify the relationship between The National Planning Policy Framework sets out the Government’s Plan policy and the planning policies for England and how these are expected to be NPPF applied. It provides the framework within which local communities and councils can produce their own distinctive local and neighbourhood plans. The Cornwall Local Plan seeks to be fully consistent with the NPPF and does not repeat national policy but sets out a clear approach for dealing with proposals. Policy 2 point 8 b) ii Amend point 8 b) ii to read: To provide clarity. ii. identifying allocating mixed use development to deliver the eco- community at West Carclaze / Baal and Par Docks. Table 2 Split table 2 into two categories; industrial floor space and office To provide clarity. floor space. Policy 7, point 2 Amend the text to read: To provide clarity 2. Reuse of suitably constructed redundant or disused buildings which are considered appropriate to retain and would lead to an V1 Schedule of Proposed Further Significant Changes March 2015 ID.01.CC.2.4 No. Paragraph/ Policy/ Change Justification Page Reference enhancement to the immediate setting. Policy 12 Amend the dates to read: To ensure that the Plan is up to date. -

Tavistock World Heritage Site Key Centre Steering Group Interpretation Strategy

Tavistock World Heritage Site Key Centre Steering Group Interpretation Strategy Andrew Thompson January 2014 Tavistock Town Centre © Barry Gamble Contents Introduction p2 1. Statement of Significance p7 2. Interpretation Audit p13 3. Audience Research p22 4. Interpretive Themes p29 5. Standards for Interpretation p44 6. Recommendations p47 7. Action Plan p59 Appendix: Tavistock Statement of Significance p62 Bibliography p76 Acknowledgement The author is grateful to Alex Mettler and Barry Gamble for their assistance in preparing this strategy. 1 Introduction This strategy sets out a framework and action plan for improving interpretation in Tavistock and for enabling the town to fulfil the requirements of a Key Centre within the Cornwall and West Devon Mining Landscape World Heritage Site (WHS). It is intended to complement the Tavistock World Heritage Site Key Centre Learning Strategy (Kell 2013) which concentrates on learning activities and people. Consequently the focus here is primarily on interpretive content and infrastructure rather than personnel. Aims and objectives The brief set by the Tavistock World Heritage Site Key Centre Steering Group was to identify a consistent, integrated approach to presenting the full range of themes arising from the Outstanding Universal Value of WHS Areas 8, 9 and 10 and to respond to the specific recommendations arising from the WHS Interpretation Strategy (WHS 2005). We were asked to: x Address interpretation priorities in the context of the Cornish Mining WHS x Identify and prioritise target audiences x Set out a clearly articulated framework and action plan for the development of interpretation provision in WHS Area 10, including recommendations which address x Product development (i.e. -

Edited by IJ Bennallick & DA Pearman

BOTANICAL CORNWALL 2010 No. 14 Edited by I.J. Bennallick & D.A. Pearman BOTANICAL CORNWALL No. 14 Edited by I.J.Bennallick & D.A.Pearman ISSN 1364 - 4335 © I.J. Bennallick & D.A. Pearman 2010 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the copyright holder. Published by - the Environmental Records Centre for Cornwall & the Isles of Scilly (ERCCIS) based at the- Cornwall Wildlife Trust Five Acres, Allet, Truro, Cornwall, TR4 9DJ Tel: (01872) 273939 Fax: (01872) 225476 Website: www.erccis.co.uk and www.cornwallwildlifetrust.org.uk Cover photo: Perennial Centaury Centaurium scilloides at Gwennap Head, 2010. © I J Bennallick 2 Contents Introduction - I. J. Bennallick & D. A. Pearman 4 A new dandelion - Taraxacum ronae - and its distribution in Cornwall - L. J. Margetts 5 Recording in Cornwall 2006 to 2009 – C. N. French 9 Fitch‟s Illustrations of the British Flora – C. N. French 15 Important Plant Areas – C. N. French 17 The decline of Illecebrum verticillatum – D. A. Pearman 22 Bryological Field Meetings 2006 – 2007 – N. de Sausmarez 29 Centaurium scilloides, Juncus subnodulosus and Phegopteris connectilis rediscovered in Cornwall after many years – I. J. Bennallick 36 Plant records for Cornwall up to September 2009 – I. J. Bennallick 43 Plant records and update from the Isles of Scilly 2006 – 2009 – R. E. Parslow 93 3 Introduction We can only apologise for the very long gestation of this number. There is so much going on in the Cornwall botanical world – a New Red Data Book, an imminent Fern Atlas, plans for a new Flora and a Rare Plant Register, plus masses of fieldwork, most notably for Natural England for rare plants on SSSIs, that somehow this publication has kept on being put back as other more urgent tasks vie for precedence. -

Cornwall Industrial Settlements Initiative LUXULYAN (Hensbarrow Area)

Report No: 2004R090 Cornwall Industrial Settlements Initiative LUXULYAN (Hensbarrow Area) 2004 CORNWALL INDUSTRIAL SETTLEMENTS INITIATIVE Conservation Area Partnership Name: Luxulyan Study Area: Hensbarrow Council: Restormel District Council NGR: SX 05249 58016 (centre) Location: South-east Cornwall, 7 miles Existing No south of Bodmin, 5 miles CA? north-east of St Austell Main period of 1840-1900 Main Granite quarries; transport industrial settlement industry: growth: Industrial history and significance In many ways Luxulyan appears to be a traditional rural churchtown, with subsidiary farming and milling settlements at Atwell and Bridges, whose economy was based around agriculture, with artisans’ cottages grouped around the central church. However, typical industrial settlement features such as the Bible Christian Chapel, public house and working men’s’ institute are also prominent, as are the remains in the wider landscape of the tin streaming, quarries and tramways which added a whole separate layer of activity to this ancient farming landscape. Always on the edge of the great industrial areas to the west and to the south, Luxulyan none-the-less was affected by their presence, creating all the range of services and building types normally associated with much larger and more entirely industrial settlements. The main local industry, granite quarrying, did not require a huge workforce or associated housing provision, nor was the scale of the railway or the 20th century china clay dry sufficient to affect the settlement much. Undoubtedly some of the local quarry and railmen lived in the village, but its main importance would have been as a provider of services rather than accommodation. In this it is reminiscent of a class of churchtown found elsewhere on the fringes of the major industrial areas, like others ringing the Hensbarrow china clay area, although less affected even than them by the industry.