Cornwall Industrial Settlements Initiative LUXULYAN (Hensbarrow Area)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INDUSTRIAL ARCHAEOLGICAL SECTION of the DEVONSHIRE ASSOCIATION Issue 5 April 2019 CONTENTS

INDUSTRIAL ARCHAEOLGICAL SECTION of the DEVONSHIRE ASSOCIATION Issue 5 April 2019 CONTENTS DATES FOR YOUR DIARY – forthcoming events Page 2 THE HEALTH OF TAMAR VALLEY MINE WORKERS 4 A report on a talk given by Rick Stewart 50TH SWWERIA CONFERENCE 2019 5 A report on the event THE WHETSTONE INDUSTRY & BLACKBOROUGH GEOLOGY 7 A report on a field trip 19th CENTURY BRIDGES ON THE TORRIDGE 8 A report on a talk given by Prof. Bill Harvey & a visit to SS Freshspring PLANNING A FIELD TRIP AND HAVING A ‘JOLLY’ 10 Preparing a visit to Luxulyan Valley IASDA / SIAS VISIT TO LUXULYAN VALLEY & BEYOND 15 What’s been planned and booking details HOW TO CHECK FOR NEW ADDITIONS TO LOCAL ARCHIVES 18 An ‘Idiots Guide’ to accessing digitized archives MORE IMAGES OF RESCUING A DISUSED WATERWHEEL 20 And an extract of family history DATES FOR YOUR DIARY: Tinworking, Mining and Miners in Mary Tavy A Community Day Saturday 27th April 2019 Coronation Hall, Mary Tavy 10:00 am—5:00 pm Open to all, this day will explore the rich legacy of copper, lead and tin mining in the Mary Tavy parish area. Two talks, a walk, exhibitions, bookstalls and afternoon tea will provide excellent stimulation for discovery and discussion. The event will be free of charge but donations will be requested for morning tea and coffee, and afternoon cream tea will be available at £4.50 per head. Please indicate your attendance by emailing [email protected] – this will be most helpful for catering arrangements. Programme 10:00 Exhibitions, bookstalls etc. -

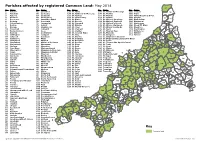

Parish Boundaries

Parishes affected by registered Common Land: May 2014 94 No. Name No. Name No. Name No. Name No. Name 1 Advent 65 Lansall os 129 St. Allen 169 St. Martin-in-Meneage 201 Trewen 54 2 A ltarnun 66 Lanteglos 130 St. Anthony-in-Meneage 170 St. Mellion 202 Truro 3 Antony 67 Launce lls 131 St. Austell 171 St. Merryn 203 Tywardreath and Par 4 Blisland 68 Launceston 132 St. Austell Bay 172 St. Mewan 204 Veryan 11 67 5 Boconnoc 69 Lawhitton Rural 133 St. Blaise 173 St. M ichael Caerhays 205 Wadebridge 6 Bodmi n 70 Lesnewth 134 St. Breock 174 St. Michael Penkevil 206 Warbstow 7 Botusfleming 71 Lewannick 135 St. Breward 175 St. Michael's Mount 207 Warleggan 84 8 Boyton 72 Lezant 136 St. Buryan 176 St. Minver Highlands 208 Week St. Mary 9 Breage 73 Linkinhorne 137 St. C leer 177 St. Minver Lowlands 209 Wendron 115 10 Broadoak 74 Liskeard 138 St. Clement 178 St. Neot 210 Werrington 211 208 100 11 Bude-Stratton 75 Looe 139 St. Clether 179 St. Newlyn East 211 Whitstone 151 12 Budock 76 Lostwithiel 140 St. Columb Major 180 St. Pinnock 212 Withiel 51 13 Callington 77 Ludgvan 141 St. Day 181 St. Sampson 213 Zennor 14 Ca lstock 78 Luxul yan 142 St. Dennis 182 St. Stephen-in-Brannel 160 101 8 206 99 15 Camborne 79 Mabe 143 St. Dominic 183 St. Stephens By Launceston Rural 70 196 16 Camel ford 80 Madron 144 St. Endellion 184 St. Teath 199 210 197 198 17 Card inham 81 Maker-wi th-Rame 145 St. -

Things to Consider When Visiting Treffry Viaduct As with All Off – Site Visits, a Preliminary Visit from the Class Teacher / Leader Is Highly Recommended

Things to consider when visiting Treffry Viaduct As with all off – site visits, a preliminary visit from the class teacher / leader is highly recommended. Following on from our workshops here, we have detailed below things we hope you will find useful when planning your visit. Getting to Treffry Viaduct Treffry viaduct is half a mile South East of Luxulyan and approximately 4 miles North of St. Austell. To get a complete sense of the Luxulyan valley and the industrial features there we advise starting the exploration at Pont’s Mill where there is a drop off carpark and walking through the Valley until you reach the viaduct. This will be the end of your journey and is near another small car park outlined below- If you don’t have time to walk up from Ponts Mill or have complications with transport, then you can always start at the viaduct and explore from here. Our experience - the main challenges The Luxulyan Valley and the Treffry Viaduct is a fascinating site that will really make children think about the challenges Joseph Treffry had to overcome in order to achieve his dream at this particular time in history. It is littered with industrial archaeology which will help the children refer back to the game they played on the first day of this project. The Valley, as a natural space is beautiful all year round with plenty of opportunities for the identification and recording of natural species. The main challenges we found when planning a visit were lack of toilets and access for children with mobility issues. -

St Blazey Fowey and Lostwithiel Cormac Community Programme

Cormac Community Programme St Blazey, Fowey and Lostwithiel Community Network Area ........ Please direct any enquiries to [email protected] ...... Project Name Anticipated Anticipated Anticipated Worktype Location Electoral Division TM Type - Primary Duration Start Finish MID MID-St Blazey Fowey & Lostwithiel Contracting St Austell Bay Resilient Regeneration (ERDF) Construction - Various Locations 443 d Jul 2020 Apr 2022 Major Contracts (MCCL) St Blazey Area Fowey Tywardreath & Par Various (See Notes) Doubletrees School, St Austell Carpark Tank 211 d Apr 2021 Feb 2022 Environmental Capital Safety Works (ENSP) St Austell St Blazey 2WTL (2 Way Signals) Luxulyan Valley_St Austell_Benches, Signs 19 d Jun 2021 Aug 2021 Environmental Capital Safety Works (ENSP) St Austell Lostwithiel & Lanreath TBC Luxulyan Valley_St Austell_Path Works 130 d Jul 2021 Feb 2022 Environmental Capital Safety Works (ENSP) St Austell Lostwithiel & Lanreath Not Required Luxulyan Valley_St Austell_Riverbank Repairs (Cam Bridges Lux Phase 1) 14 d Aug 2021 Sep 2021 Environmental Capital Safety Works (ENSP) St Austell Lostwithiel & Lanreath Not Required Luxulyan Valley_St Austell_Drainage Feature (Leat Repairs Trail) 15 d Sep 2021 Sep 2021 Environmental Capital Safety Works (ENSP) St Austell Lostwithiel & Lanreath TBC Bull Engine, Par -Skate Park Equipment Design & Installation 10 d Nov 2021 Nov 2021 Environmental Capital Safety Works (ENSP) Par Fowey Tywardreath & Par Not Required Luxulyan Valley, St Austell -Historic Structures 40 d Nov 2021 Jan 2022 Environmental -

Environmental Protection Final Draft Report

Environmental Protection Final Draft Report ANNUAL CLASSIFICATION OF RIVER WATER QUALITY 1992: NUMBERS OF SAMPLES EXCEEDING THE QUALITY STANDARD June 1993 FWS/93/012 Author: R J Broome Freshwater Scientist NRA C.V.M. Davies National Rivers Authority Environmental Protection Manager South West R egion ANNUAL CLASSIFICATION OF RIVER WATER QUALITY 1992: NUMBERS OF SAMPLES EXCEEDING TOE QUALITY STANDARD - FWS/93/012 This report shows the number of samples taken and the frequency with which individual determinand values failed to comply with National Water Council river classification standards, at routinely monitored river sites during the 1992 classification period. Compliance was assessed at all sites against the quality criterion for each determinand relevant to the River Water Quality Objective (RQO) of that site. The criterion are shown in Table 1. A dashed line in the schedule indicates no samples failed to comply. This report should be read in conjunction with Water Quality Technical note FWS/93/005, entitled: River Water Quality 1991, Classification by Determinand? where for each site the classification for each individual determinand is given, together with relevant statistics. The results are grouped in catchments for easy reference, commencing with the most south easterly catchments in the region and progressing sequentially around the coast to the most north easterly catchment. ENVIRONMENT AGENCY 110221i i i H i m NATIONAL RIVERS AUTHORITY - 80UTH WEST REGION 1992 RIVER WATER QUALITY CLASSIFICATION NUMBER OF SAMPLES (N) AND NUMBER -

Below 2014.1

Quarterly Journal of the Shropshire Caving & Mining Club Spring Issue No: 2014.1 Sinkhole - the ‘IN’ word for 2014 The media seem to have discovered Caver Mark Noble provided the the word ‘Sinkhole’ this year, with photographs, but I think his wife almost every news report mentioning was taking a chance posing on the one opening up somewhere in collapsing edge in the one picture! Britain. While sinkholes are relatively rare in Broseley joined in with a hole The Broseley hole - covered with a Britain, they are regular occurrences opening up into old coal workings board. (Kelvin Lake - I.A.Recordings) in the USA where horror stories under the main road between However, this hole is small abound of people disappearing down Ironbridge and Broseley at compared to some of the holes holes while they sleep! Christmas. The Club’s Christmas that have been opening up in walk around Jackfield took a slight places such as Hemel Hempstead, The National Corvette Museum detour to view the hole - but it was Rickmansworth, Ripon and even in in Kentucky has been the latest cunningly hidden under a wooden the central reservation of the M2. victim. A sinkhole opened up inside panel. However we were assured that the museum on the 12th February it was much bigger underground, so All of these have occurred in chalk swallowing 8 vintage Corvettes - the road has been closed until the or gypsum areas and are probably including the historic 1 millionth Coal Authority can sort it out. natural solution holes caused by Corvette and rare cars on loan from General Motors. -

Luxulyan Neighbourhood Development Plan 2018 - 2030

Luxulyan Neighbourhood Development Plan 2018 - 2030 Produced by the Luxulyan Neighbourhood Development Plan Steering Group 9th May 2019 Page | 1 CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction 2.0 The Neighbourhood Development Plan Process 3.0 Guidelines 4.0 Description of the Parish 5.0 View of the Community 6.0 Vision and aims 7.0 Housing Requirement 8.0 Policies 9.0 Local Landscape Character 10.0 Evidence Documents and Background Reference Page | 2 1. Introduction 1.1 Neighbourhood planning gives the Luxulyan community direct power to develop a shared vision and to shape the development and growth of the local area. The community are able to choose if, and where they want new homes to be built, have their say on what those new homes should look like and what infrastructure should be provided, and directly influence the grant of planning permission for the new homes they want to see go ahead. 1.2 A Neighbourhood Development Plan concerns the future development in the Parish. It is also about the use of land and the environment. The plan must take into account what local people want and can only be approved once a local referendum has taken place. The neighbourhood development plan will form part of the statutory Development Plan for the Parish and therefore planning decisions need to be made in accordance with the neighbourhood development plan. 1.3 The creation of a Neighbourhood Development Plan is part of the government’s approach to planning, as contained in the Localism Act 2011. 1.4 Luxulyan Parish Council applied to Cornwall Council, on 4th June 2016, to designate the Parish as a “Neighbourhood Area.” Cornwall Council formally designated the Neighbourhood Area on 4th August 2016 in accordance with the Neighbourhood Planning (General) Regulations 2012. -

Environmentol Protection Report WATER QUALITY MONITORING

5k Environmentol Protection Report WATER QUALITY MONITORING LOCATIONS 1992 April 1992 FW P/9 2/ 0 0 1 Author: B Steele Technicol Assistant, Freshwater NRA National Rivers Authority CVM Davies South West Region Environmental Protection Manager HATER QUALITY MONITORING LOCATIONS 1992 _ . - - TECHNICAL REPORT NO: FWP/92/001 The maps in this report indicate the monitoring locations for the 1992 Regional Water Quality Monitoring Programme which is described separately. The presentation of all monitoring features into these catchment maps will assist in developing an integrated approach to catchment management and operation. The water quality monitoring maps and index were originally incorporated into the Catchment Action Plans. They provide a visual presentation of monitored sites within a catchment and enable water quality data to be accessed easily by all departments and external organisations. The maps bring together information from different sections within Water Quality. The routine river monitoring and tidal water monitoring points, the licensed waste disposal sites and the monitored effluent discharges (pic, non-plc, fish farms, COPA Variation Order [non-plc and pic]) are plotted. The type of discharge is identified such as sewage effluent, dairy factory, etc. Additionally, river impact and control sites are indicated for significant effluent discharges. If the watercourse is not sampled then the location symbol is qualified by (*). Additional details give the type of monitoring undertaken at sites (ie chemical, biological and algological) and whether they are analysed for more specialised substances as required by: a. EC Dangerous Substances Directive b. EC Freshwater Fish Water Quality Directive c. DOE Harmonised Monitoring Scheme d. DOE Red List Reduction Programme c. -

Cornwall Local Plan: Community Network Area Sections

Planning for Cornwall Cornwall’s future Local Plan Strategic Policies 2010 - 2030 Community Network Area Sections www.cornwall.gov.uk Dalghow Contents 3 Community Networks 6 PP1 West Penwith 12 PP2 Hayle and St Ives 18 PP3 Helston and South Kerrier 22 PP4 Camborne, Pool and Redruth 28 PP5 Falmouth and Penryn 32 PP6 Truro and Roseland 36 PP7 St Agnes and Perranporth 38 PP8 Newquay and St Columb 41 PP9 St Austell & Mevagissey; China Clay; St Blazey, Fowey & Lostwithiel 51 PP10 Wadebridge and Padstow 54 PP11 Bodmin 57 PP12 Camelford 60 PP13 Bude 63 PP14 Launceston 66 PP15 Liskeard and Looe 69 PP16 Caradon 71 PP17 Cornwall Gateway Note: Penzance, Hayle, Helston, Camborne Pool Illogan Redruth, Falmouth Penryn, Newquay, St Austell, Bodmin, Bude, Launceston and Saltash will be subject to the Site Allocations Development Plan Document. This document should be read in conjunction with the Cornwall Local Plan: Strategic Policies 2010 - 2030 Community Network Area Sections 2010-2030 4 Planning for places unreasonably limiting future opportunity. 1.4 For the main towns, town frameworks were developed providing advice on objectives and opportunities for growth. The targets set out in this plan use these as a basis for policy where appropriate, but have been moderated to ensure the delivery of the wider strategy. These frameworks will form evidence supporting Cornwall Allocations Development Plan Document which will, where required, identify major sites and also Neighbourhood Development Plans where these are produced. Town frameworks have been prepared for; Bodmin; Bude; Camborne-Pool-Redruth; Falmouth Local objectives, implementation & Penryn; Hayle; Launceston; Newquay; Penzance & Newlyn; St Austell, St Blazey and Clay Country and monitoring (regeneration plan) and St Ives & Carbis Bay 1.1 The Local Plan (the Plan) sets out our main 1.5 The exception to the proposed policy framework planning approach and policies for Cornwall. -

Gardens Guide

Gardens of Cornwall map inside 2015 & 2016 Cornwall gardens guide www.visitcornwall.com Gardens Of Cornwall Antony Woodland Garden Eden Project Guide dogs only. Approximately 100 acres of woodland Described as the Eighth Wonder of the World, the garden adjoining the Lynher Estuary. National Eden Project is a spectacular global garden with collection of camellia japonica, numerous wild over a million plants from around the World in flowers and birds in a glorious setting. two climatic Biomes, featuring the largest rainforest Woodland Garden Office, Antony Estate, Torpoint PL11 3AB in captivity and stunning outdoor gardens. Enquiries 01752 814355 Bodelva, St Austell PL24 2SG Email [email protected] Enquiries 01726 811911 Web www.antonywoodlandgarden.com Email [email protected] Open 1 Mar–31 Oct, Tue-Thurs, Sat & Sun, 11am-5.30pm Web www.edenproject.com Admissions Adults: £5, Children under 5: free, Children under Open All year, closed Christmas Day and Mon/Tues 5 Jan-3 Feb 16: free, Pre-Arranged Groups: £5pp, Season Ticket: £25 2015 (inclusive). Please see website for details. Admission Adults: £23.50, Seniors: £18.50, Children under 5: free, Children 6-16: £13.50, Family Ticket: £68, Pre-Arranged Groups: £14.50 (adult). Up to 15% off when you book online at 1 H5 7 E5 www.edenproject.com Boconnoc Enys Gardens Restaurant - pre-book only coach parking by arrangement only Picturesque landscape with 20 acres of Within the 30 acre gardens lie the open meadow, woodland garden with pinetum and collection Parc Lye, where the Spring show of bluebells is of magnolias surrounded by magnificent trees. -

The Bryophytes of Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly

THE BRYOPHYTES OF CORNWALL AND THE ISLES OF SCILLY by David T. Holyoak Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................ 2 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 3 Scope and aims .......................................................................... 3 Coverage and treatment of old records ...................................... 3 Recording since 1993 ................................................................ 5 Presentation of data ................................................................... 6 NOTES ON SPECIES .......................................................................... 8 Introduction and abbreviations ................................................. 8 Hornworts (Anthocerotophyta) ................................................. 15 Liverworts (Marchantiophyta) ................................................. 17 Mosses (Bryophyta) ................................................................. 98 COASTAL INFLUENCES ON BRYOPHYTE DISTRIBUTION ..... 348 ANALYSIS OF CHANGES IN BRYOPHYTE DISTRIBUTION ..... 367 BIBLIOGRAPHY ................................................................................ 394 1 Acknowledgements Mrs Jean A. Paton MBE is thanked for use of records, gifts and checking of specimens, teaching me to identify liverworts, and expertise freely shared. Records have been used from the Biological Records Centre (Wallingford): thanks are due to Dr M.O. Hill and Dr C.D. Preston for -

Cornwall Walks

Introduction Walking Please remember all public rights of way cross private land, The branch lines of Cornwall offer some of the most scenic so keep to paths and keep dogs on leads. Occasionally short term work may mean diversions train journeys in Britain. are put in place, follow local signs From stunning if necessary. coastal views along the St Ives Bay The maps in this booklet are intended Line to the beauty as a guide only; it is always of the Looe Valley advisable to carry the and the spectacular appropriate OS Map views from Calstock with you whilst out Viaduct on the walking. Tamar Valley Line, St Ives Bay Line there is plenty to St Keyne Wishing explore by rail and Well Halt Station then on foot. to Causeland Gunnislake Station In this booklet, you will find nine walks from stations across Pages 16 & 17 to Calstock Cornwall to enjoy. You can Pages 18 & 19 Luxulyan Mining find more walks at our website www.greatscenicrailways.com Heritage Circular Luxulyan Pages 12 & 13 Gunnislake and in the Devon version of this to Eden Calstock Bere Alston booklet too. Pages 10 & 11 Bere Ferrers St Budeaux LISKEARD Keyham NEWQUAY Coombe Valley Junction Penryn to Falmouth Quintrell Downs St Keyne Victoria Road St Columb Road Causeland Luxulyan via Flushing Roche Sandplace Bugle PLYMOUTH Pages 8 & 9 Par LOOE TRURO Looe to Calstock Station Carbis Bay Perrranwell Polperro Carbis Bay ST IVES Lelant to Cotehele House Lelant Saltings Penryn Pages 14 & 15 Pages 20 & 21 to Porthminster Beach Penmere St Erth FALMOUTH Pages 4 & 5 PENZANCE Perranwell Village Circular Pages 6 & 7 ST IVES BAY LINE DISTANCE 1¼ MILES Carbis Bay to Porthminster Beach The main route continues along a surfaced road, past From the station car park, go down the road towards the houses.