Alternative Interpretations of the Rhetoric Used in William Friedkin and William Peter Blatty’S the Exorcist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

See It Big! Action Features More Than 30 Action Movie Favorites on the Big

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ‘SEE IT BIG! ACTION’ FEATURES MORE THAN 30 ACTION MOVIE FAVORITES ON THE BIG SCREEN April 19–July 7, 2019 Astoria, New York, April 16, 2019—Museum of the Moving Image presents See It Big! Action, a major screening series featuring more than 30 action films, from April 19 through July 7, 2019. Programmed by Curator of Film Eric Hynes and Reverse Shot editors Jeff Reichert and Michael Koresky, the series opens with cinematic swashbucklers and continues with movies from around the world featuring white- knuckle chase sequences and thrilling stuntwork. It highlights work from some of the form's greatest practitioners, including John Woo, Michael Mann, Steven Spielberg, Akira Kurosawa, Kathryn Bigelow, Jackie Chan, and much more. As the curators note, “In a sense, all movies are ’action’ movies; cinema is movement and light, after all. Since nearly the very beginning, spectacle and stunt work have been essential parts of the form. There is nothing quite like watching physical feats, pulse-pounding drama, and epic confrontations on a large screen alongside other astonished moviegoers. See It Big! Action offers up some of our favorites of the genre.” In all, 32 films will be shown, many of them in 35mm prints. Among the highlights are two classic Technicolor swashbucklers, Michael Curtiz’s The Adventures of Robin Hood and Jacques Tourneur’s Anne of the Indies (April 20); Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (April 21); back-to-back screenings of Mad Max: Fury Road and Aliens on Mother’s Day (May 12); all six Mission: Impossible films -

DC City Guide

DC City Guide Page | 1 Washington, D.C. Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States and the seat of its three branches of government, has a collection of free, public museums unparalleled in size and scope throughout the history of mankind, and the lion's share of the nation's most treasured monuments and memorials. The vistas on the National Mall between the Capitol, Washington Monument, White House, and Lincoln Memorial are famous throughout the world as icons of the world's wealthiest and most powerful nation. Beyond the Mall, D.C. has in the past two decades shed its old reputation as a city both boring and dangerous, with shopping, dining, and nightlife befitting a world-class metropolis. Travelers will find the city new, exciting, and decidedly cosmopolitan and international. Districts Virtually all of D.C.'s tourists flock to the Mall—a two-mile long, beautiful stretch of parkland that holds many of the city's monuments and Smithsonian museums—but the city itself is a vibrant metropolis that often has little to do with monuments, politics, or white, neoclassical buildings. The Smithsonian is a "can't miss," but don't trick yourself—you haven't really been to D.C. until you've been out and about the city. Page | 2 Downtown (The National Mall, East End, West End, Waterfront) The center of it all: The National Mall, D.C.'s main theater district, Smithsonian and non- Smithsonian museums galore, fine dining, Chinatown, the Verizon Center, the Convention Center, the central business district, the White House, West Potomac Park, the Kennedy Center, George Washington University, the beautiful Tidal Basin, and the new Nationals Park. -

Yearbooks Are Going on Sale Who Consistently Lives Life to the Fullest

October 15, 2014 Volume XXI Hawk Issue 2 Happenings A Publication of Hamburg Area High School, Windsor Street, Hamburg, PA 19526 HAHS adopts Root Word of the Week Brooke Buckley Julian Warner - 12 is Hamburg’s Thorough consideration, the fall of the Hamburg Area High School Latin program, and untapped standardized testing potential has coalesced into an initiative to permeate the ancient Greek and Latin lexicons throughout the entire student body. It is known as the Outstanding Young “Root Word[s] of the Week”. The ostensible arbitrariness of the initiative has left students curious, indifferent, or sometimes dubious. Nevertheless, approbating administrative figures offer research-backed certitude that there is, indeed, method to the madness. Woman Since the 2012-2013 school year, elementary schools in the Hamburg Area School Sarah Hanlon – 12 District have embraced the Root Word of the Week System. Since doing so, the idea has spread throughout all of the levels of primary education in Hamburg, eventually arriving at On Saturday, October 4, Brooke Buckley HAHS. Teachers of varying subjects review the root words, along with their applications represented Hamburg Area High School in the Berks to modern English, with the students throughout the week. Typically, the words are County Outstanding Young Woman program. Brooke selected thematically from a larger list of pre-selected root words. During the Labor Day was one of 19 female high school seniors in Berks holiday, for example, oper- and erg- (both meaning “work”) were taught as root words. County who participated in the scholarship event. The The root word initiative is not exclusive to the Hamburg education system, contestants participated in a yearly competition that and it can be found in numerous schools throughout the United States, both focuses on academic and community service excellence, as well as performing arts and nearby and afar. -

Appalling! Terrifying! Wonderful! Blaxploitation and the Cinematic Image of the South

Antoni Górny Appalling! Terrifying! Wonderful! Blaxploitation and the Cinematic Image of the South Abstract: The so-called blaxploitation genre – a brand of 1970s film-making designed to engage young Black urban viewers – has become synonymous with channeling the political energy of Black Power into larger-than-life Black characters beating “the [White] Man” in real-life urban settings. In spite of their urban focus, however, blaxploitation films repeatedly referenced an idea of the South whose origins lie in antebellum abolitionist propaganda. Developed across the history of American film, this idea became entangled in the post-war era with the Civil Rights struggle by way of the “race problem” film, which identified the South as “racist country,” the privileged site of “racial” injustice as social pathology.1 Recently revived in the widely acclaimed works of Quentin Tarantino (Django Unchained) and Steve McQueen (12 Years a Slave), the two modes of depicting the South put forth in blaxploitation and the “race problem” film continue to hold sway to this day. Yet, while the latter remains indelibly linked, even in this revised perspective, to the abolitionist vision of emancipation as the result of a struggle between idealized, plaintive Blacks and pathological, racist Whites, blaxploitation’s troping of the South as the fulfillment of grotesque White “racial” fantasies offers a more powerful and transformative means of addressing America’s “race problem.” Keywords: blaxploitation, American film, race and racism, slavery, abolitionism The year 2013 was a momentous one for “racial” imagery in Hollywood films. Around the turn of the year, Quentin Tarantino released Django Unchained, a sardonic action- film fantasy about an African slave winning back freedom – and his wife – from the hands of White slave-owners in the antebellum Deep South. -

Exorcism Part 1

Exorcism 101 Let us start by Explaining what Exorcism is Not. Exorcism is not a Game it is quite real if you do not believe this, please do not try to do, or play at trying to do, An Exorcism; it can get you Killed,, or the one you are helping Killed those around you killed; the best trick the devil did is convince others He does not exist. He does not need you to believe to be real; he is, whether you like it our not; he does not play games. Evil will fight for what they think is theirs; just remember the Movie the EXORCIST it was and really did happen but it was a Young Man not a Girl and priests were killed and others very badly injured; there are others as well. Not so well known, in each case the Exorcist forgot the First Rule: YOU Are not the one casting it out, God working in you is and do not lose your faith; Fast, Prayer, Confession. Be for ever trying and remember I Repeat it again: ITS the Power OF God Not you, Casting out the Evil. Another mistake: they forget to Bind it way from all, so it can do no harm, and never think you are stronger than what you are fighting; you are not. This said let us go on to what Exorcism is for there is a lot of info. I will use things already out on the web to save time from scanning and up-loading out of my own notes and add to them what I think may be missing; let us begin with: CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA (See also DEMONOLOGY, DEMONIACS, EXORCIST, POSSESSION.) Exorcism is (1) the act of driving out, or warding off, demons, or evil spirits, from persons, places, or things, which are believed to be possessed or infested by them, or are liable to become victims or instruments of their malice; (2) the means employed for this purpose, especially the solemn and authoritative adjuration of the demon, in the name of God, or any of the higher power in which he is subject. -

October 18 - November 28, 2019 Your Movie! Now Serving!

Grab a Brew with October 18 - November 28, 2019 your Movie! Now Serving! 905-545-8888 • 177 SHERMAN AVE. N., HAMILTON ,ON • WWW.PLAYHOUSECINEMA.CA WINNER Highest Award! Atwood is Back at the Playhouse! Cannes Film Festival 2019! - Palme D’or New documentary gets up close & personal Tiff -3rd Runner - Up Audience Award! with Canada’ international literary star! This black comedy thriller is rated 100% on Rotten Tomatoes. Greed and class discrimination threaten the newly formed symbiotic re- MARGARET lationship between the wealthy Park family and the destitute Kim clan. ATWOOD: A Word After a Word “HHHH, “Parasite” is unquestionably one of the best films of the year.” After a Word is Power. - Brian Tellerico Rogerebert.com ONE WEEK! Nov 8-14 Playhouse hosting AGH Screenings! ‘Scorcese’s EPIC MOB PICTURE is HEADED to a Best Picture Win at Oscars!” - Peter Travers , Rolling Stone SE LAYHOU 2! AGH at P 27! Starts Nov 2 Oct 23- OPENS Nov 29th Scarlett Johansson Laura Dern Adam Driver Descriptions below are for films playing at BEETLEJUICE THE CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI Dir.Tim Burton • USA • 1988 • 91min • Rated PG. FEAT. THE VOC HARMONIC ORCHESTRA the Playhouse Cinema from October 18 2019, Dir. Paul Downs Colaizzo • USA • 2019 • 103min • Rated STC. through to and including November 28, 2019. TIM BURTON’S HAUNTED CLASSIC “Beetlejuice, directed by Tim Burton, is a ghost story from the LIVE MUSICAL ACCOMPANIMENT • CO-PRESENTED BY AGH haunters' perspective.The drearily happy Maitlands (Alec Baldwin and Iconic German Expressionist silent horror - routinely cited as one of Geena Davis) drive into the river, come up dead, and return to their the greatest films ever made - presented with live music accompani- Admission Prices beloved, quaint house as spooks intent on despatching the hideous ment by the VOC Silent Film Harmonic, from Kitchener-Waterloo. -

Creative Consultant Teller and Composer Sir John Tavener Help Make the Exorcist a Sensory Feast

CREATIVE CONSULTANT TELLER AND COMPOSER SIR JOHN TAVENER HELP MAKE THE EXORCIST A SENSORY FEAST Director John Doyle’s Creative Team Also Includes Tony Award Winning Scenic/Costume Designer Scott Pask, Lighting Designer Jane Cox and Sound Designer Dan Moses Schreier LOS ANGELES, May 29, 2012 — In addition to an accomplished cast, the Geffen Playhouse’s world premiere stage adaptation of The Exorcist showcases an award-winning design team – including world-renowned creative consultant Teller and internationally acclaimed spiritual composer Sir John Tavener – to bring playwright John Pielmeier’s script and Tony Award winning director John Doyle’s vision to life on stage. The team also includes Tony Award winning scenic/costume designer Scott Pask, lighting designer Jane Cox and sound designer Dan Moses Schreier. Working with Doyle, the design team will be tasked with creating a theatrical experience that engages the senses in a way that is unique to live performance. As the designers create ambiance and atmosphere, the actors taking center stage include Brooke Shields and Richard Chamberlain in the iconic roles of Chris MacNeil and Father Merrin, respectively, as well as Broadway actor David Wilson Barnes as the troubled young priest Father Damien Karras, Tony Award nominee Harry Groener takes on the role of Chris’ charismatic director Burke Dennings and UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television graduate Emily Yetter plays the young Regan MacNeil. The world premiere cast also includes Stephen Bogardus, Manoel Felciano, Tom Nelis and Roslyn Ruff. The Exorcist opens in the Gil Cates Theater at the Geffen Playhouse on July 11, 2012 and runs through August, 12, 2012. -

The Exorcist" - - Textual --Topical Scripture Reading'------Devotional

SATAN SUBJECT CLASSIFICATION: TEXT Deuteronomy 18:9-13 --EXPOSITORY --BIOGRAPHICAL _____________________"THE EXORCIST" - - TEXTUAL --TOPICAL SCRIPTURE READING'---------------- ---DEVOTIONAL DELIVERIES: Date Hour Place Results and Comments: F.B.C. 8-8-82 p.m. San Angelo, TX (XXX+++) F.B.C. p.m. San Angelo, TX (XXXX++++) 5L; lB; 1 Sp. Ser. BIBLIOGRAPHY------------ E.F. CLASSIFICATION: TEXT ---EXPOSITORY "THE EXORCIST" - - BIOGRAPHICAL --- TEXTUAL --TOPICAL SCRIPTURE READING·- ---------- ----- --DEVOTIONAL DELIVERIES: Date Hour Place Results and Comments: FBC 4-21-74 a.m. San Angelo, Texas XXX++++ FBC 8-8-82 p.m. San Angelo, Texas XXX+++ BIBLIOGRAPHY _ I Scripture: Deut.1 8:9-13 '17 · ntro: f the The Exorcist, continues at its present level of success it has every chance of becoming the most widely viewed movie in the world as well as the first billion dollar producer. During its week it grossed $2,000,000. Newsweek, average 9 a day faint ... The movie is based on William Peter Blatty' s book, The Exorcist, which relates a reported experience in 1949 of a demon-possessed 14 year old boy living in Mt. Ranier, Maryland, adjacent to Washington, D. C. Blatty was a student at Georgetown University at that time and attended a series of lectures by a Jesuit R.C . priest, Franci s Galiger, who centered his lectures on a case s tudy of this 14 year old boy. Phillip Hannon, now in Orleans, was in the Washington diocese when the exorcism of the boy was originally performed. The archbishop contends that Blatty has committed a real travisty with the historical facts of the case of the exorcism. -

FINAL REPORT of Special Committee on Marvin Center Name

Report of the Special Committee on the Marvin Center Name March 30, 2021 I. INTRODUCTION Renaming Framework The George Washington University Board of Trustees approved, in June of 2020, a “Renaming Framework,” designed to govern and direct the process of evaluating proposals for the renaming of buildings and memorials on campus.1 The Renaming Framework was drafted by a Board of Trustees- appointed Naming Task Force, chaired by Trustee Mark Chichester, B.B.A. ’90, J.D. ’93. The Task Force arrived at its Renaming Framework after extensive engagement with the GW community.2 Under the Renaming Framework, the university President is to acknowledge and review requests or petitions related to the renaming of buildings or spaces on campus. If the President finds a request for renaming “to be reasonably compelling when the guiding principles are applied to the particular facts,” the President is to: (1) “consult with the appropriate constituencies, such as the Faculty Senate Executive Committee, leadership of the Student Association, and the Executive Committee of the GW Alumni Association, on the merits of the request for consideration”; and (2) “appoint a special committee to research and evaluate the merits of the request for reconsideration.”3 Appointment of the Special Committee President LeBlanc established the Special Committee on the Marvin Center Name in July of 2020, and appointed Roger A. Fairfax, Jr., Patricia Roberts Harris Research Professor at the Law School as Chair. The Special Committee consists of ten members, representing students, staff, faculty, and alumni of the university, and two advisers, both of whom greatly assisted the Special Committee in its work.4 The Special Committee’s Charge Under the Renaming Framework, the charge of the Special Committee is quite narrow. -

SPRING 1966 GEORGETOWN Is Published in the Fall, Winter, and Spring by the Georgetown University Alumni Association, 3604 0 Street, Northwest, Washington, D

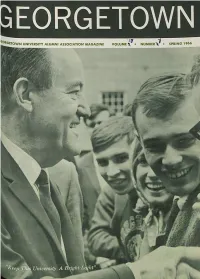

SPRING 1966 GEORGETOWN is published in the Fall, Winter, and Spring by the Georgetown University Alumni Association, 3604 0 Street, Northwest, Washington, D. C. 20007 Officers of the Georgetown University Alumni Association President Eugene L. Stewart, '48, '51 Vice-Presidents CoUege, David G. Burton, '56 Graduate School, Dr. Hartley W. Howard, '40 School of Medicine, Dr. Charles Keegan, '47 School of Law, Robert A. Marmet, '51 School of Dentistry, Dr. Anthony Tylenda, '55 School of Nursing, Miss Mary Virginia Ruth, '53 School of Foreign Service, Harry J. Smith, Jr., '51 School of Business Administration, Richard P. Houlihan, '54 Institute of Languages and Linguistics, Mrs. Diana Hopkins Baxter, '54 Recording Secretary Miss Rosalia Louise Dumm, '48 Treasurer Louis B. Fine, '25 The Faculty Representative to the Alumni Association Reverend Anthony J . Zeits, S.J., '43 The Vice-President of the University for Alumni Affairs and Executive Secretary of the Association Bernard A. Carter, '49 Acting Editor contents Dr. Riley Hughes Designer Robert L. Kocher, Sr. Photography Bob Young " Keep This University A Bright Light' ' Page 1 A Year of Tradition, Tribute, Transition Page 6 GEORGETOWN Georgetown's Medical School: A Center For Service Page 18 The cover for this issue shows the Honorable Hubert H. Humphrey, Vice On Our Campus Page 23 President of the United States, being Letter to the Alumni Page 26 greeted by students in the Yard before 1966 Official Alumni historic Old North preceding his ad Association Ballot Page 27 dress at the Founder's Day Luncheon. Book Review Page 28 Our Alumni Correspondents Page 29 "Keep This University A Bright Light" The hard facts of future needs provided a con the great documents of our history," Vice President text of urgency and promise for the pleasant recol Humphrey told the over six hundred guests at the lection of past achievements during the Founder's Founder's Day Luncheon in New South Cafeteria. -

Catholics, Whiteness, and the Movies, 1928 - 1973 Albert William Vogt III Loyola University Chicago, [email protected]

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2013 The oC stumed Catholic: Catholics, Whiteness, and the Movies, 1928 - 1973 Albert William Vogt III Loyola University Chicago, [email protected] Recommended Citation Vogt, Albert William III, "The osC tumed Catholic: Catholics, Whiteness, and the Movies, 1928 - 1973" (2013). Dissertations. Paper 693. http://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/693 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2013 Albert William Vogt III LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO THE COSTUMED CATHOLIC: CATHOLICS, WHITENESS, AND THE MOVIES, 1928–1973 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN AMERICAN HISTORY BY ALBERT W. VOGT III CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2013 Copyright by Albert W. Vogt III, 2013 All rights reserved. To my parents TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES v ABSTRACT vi CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER TWO: THE CLOAK OF WHITENESS POPULAR REPRESENTATIONS OF CATHOLCS IN THE NINETEENTH AND EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURIES 43 CHAPTER THREE: MAKING THE CATHOLIC WHITE THE RISE OF CATHOLIC INFLUENCE ON THE MOVIES, 1928–49 92 CHAPTER FOUR: REMOVING THE WHITE MASK THE DECLINE OF CATHOLIC -

The New Hollywood Films

The New Hollywood Films The following is a chronological list of those films that are generally considered to be "New Hollywood" productions. Shadows (1959) d John Cassavetes First independent American Film. Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966) d. Mike Nichols Bonnie and Clyde (1967) d. Arthur Penn The Graduate (1967) d. Mike Nichols In Cold Blood (1967) d. Richard Brooks The Dirty Dozen (1967) d. Robert Aldrich Dont Look Back (1967) d. D.A. Pennebaker Point Blank (1967) d. John Boorman Coogan's Bluff (1968) – d. Don Siegel Greetings (1968) d. Brian De Palma 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) d. Stanley Kubrick Planet of the Apes (1968) d. Franklin J. Schaffner Petulia (1968) d. Richard Lester Rosemary's Baby (1968) – d. Roman Polanski The Producers (1968) d. Mel Brooks Bullitt (1968) d. Peter Yates Night of the Living Dead (1968) – d. George Romero Head (1968) d. Bob Rafelson Alice's Restaurant (1969) d. Arthur Penn Easy Rider (1969) d. Dennis Hopper Medium Cool (1969) d. Haskell Wexler Midnight Cowboy (1969) d. John Schlesinger The Rain People (1969) – d. Francis Ford Coppola Take the Money and Run (1969) d. Woody Allen The Wild Bunch (1969) d. Sam Peckinpah Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice (1969) d. Paul Mazursky Butch Cassidy & the Sundance Kid (1969) d. George Roy Hill They Shoot Horses, Don't They? (1969) – d. Sydney Pollack Alex in Wonderland (1970) d. Paul Mazursky Catch-22 (1970) d. Mike Nichols MASH (1970) d. Robert Altman Love Story (1970) d. Arthur Hiller Airport (1970) d. George Seaton The Strawberry Statement (1970) d.