Michelangelo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

10/03/2020 | Casabella

Mensile Data 03-2020 Pagina 90/93 Mira Foglio 2 / 4 presso lo IUAV solo dal 1959, era disattenzione per la letteratura (cfr. per esempio le utilità, intorno agli anni Trenta, del sinora conosciuta solo per parti conservazione fisica dell'eredità informazioni fornite dal libro "suburbio" fiorentino, cioè la chiuse in se stesse: il dell'architettura italiana del Deutsche Architekten in «fascia del territorio comunale coinvolgimento con il Futurismo e Novecento. Großritannien di A. Schätzke del acquisito a seguito della riforma i suoi protagonisti —Marinetti, 2014). I coniugi Pritchard, Coates, i amministrativa del 1865 e del Depero, Dormal; l'importante ciclo loro amici e sodali erano socialisti e piano di ampliamento redatto e di lavori per il Partito Nazionale fautori di stili di vita estremamente diretto da Giuseppe Poggi», Fascista padovano del 1937-40 tolleranti, a iniziare dal culto perla quando Firenze fu capitale. La —tra altre, le sedi dei gruppi rionali libertà sessuale. Anche per queste scelta del Pucci è sempre quella di fascisti Bonservizi e Cappellozza, ragioni Lawn Road Flats divenne il privilegiare i giardini per il loro quest'ultima provvista di un Teatro "centro" di una intensa vita eoltre a «significato "orticolo"», «pregio all'aperto dei Diecimila, l'unico Gropius, Breuer, Moholy-Nagy, originale» della sua opera. Dei 283 "teatro di masse" realizzato in Adrian Stokes anche Agatha casi trattati, ne spiccano tre: la villa Italia, demolito negli anni Christie, il cui vicino di casa, Arnold e giardino dei Demidoff, la cui -

Peter Lanyon's Biography

First Crypt Group installation, 1946 Lanyon by Charles Gimpel Studio exterior, Little Park Owles c. 1955 Rosewall in progress 1960 Working on the study for the Liverpool mural 1960 On Porthchapel beach, Cornwall PETER Lanyon Peter Lanyon Zennor 1936 Oil on canvas November: Awarded second prize in John Sheila Lanyon Moores Exhibition, Liverpool for Offshore. Exterior, Attic Studio, St Ives February: Solo exhibition, Catherine Viviano Records slide lecture for British Council. February: Resigns from committee of Penwith Gallery, New York. Included in Sam Hunter’s European Painting Wartime, Middle East, 1942–3 Society. January: One of Three British Painters at and Sculpture Today, Minneapolis Institute of January: Solo exhibition, Fore Street Gallery, Passedoit Gallery, New York. Later, Motherwell throws a party for PL who Art and tour. St Ives. Construction 1941 March: Demobilised from RAF and returns Spring: ‘The Face of Penwith’ article, Cornish meets Mark Rothko and many other New At Little Park Owles late 1950s April: Travels to Provence where he visits Aix March –July: Stationed in Burg el Arab, fifty to St Ives. Review, no 4. January–April: Italian government scholarship York artists. Visiting Lecturer at Falmouth College of Art January: Solo exhibition, Catherine Viviano March–April: Visiting painter, San Antonio and paints Le Mont Ste Victoire. miles west of Alexandria. March: Exhibits in Danish, British and – spends two weeks in Rome and rents and West of England College, Bristol. Gallery, New York. Art Institute, Texas, during which time he April: Marries Sheila Browne. 6 February: Among the ‘moderns’ who March: Exhibits in London–Paris at the ICA, American Abstract Artists at Riverside studio at Anticoli Corrado in the Abruzzi June: Joins Perranporth gliding club. -

Michael Kidner Interviewed by Penelope Curtis

NATIONAL LIFE STORIES ARTISTS’ LIVES Michael Kidner Interviewed by Penelope Curtis & Cathy Courtney C466/40 This transcript is copyright of the British Library Board. Please refer to the Oral History curators at the British Library prior to any publication or broadcast from this document. Oral History The British Library 96 Euston Road London NW1 2DB 020 7412 7404 [email protected] This transcript is accessible via the British Library’s Archival Sound Recordings website. Visit http://sounds.bl.uk for further information about the interview. © The British Library Board http://sounds.bl.uk IMPORTANT Access to this interview and transcript is for private research only. Please refer to the Oral History curators at the British Library prior to any publication or broadcast from this document. Oral History The British Library 96 Euston Road London NW1 2DB 020 7412 7404 [email protected] Every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of this transcript, however no transcript is an exact translation of the spoken word, and this document is intended to be a guide to the original recording, not replace it. Should you find any errors please inform the Oral History curators ( [email protected] ) © The British Library Board http://sounds.bl.uk The British Library National Life Stories Interview Summary Sheet Title Page Ref no: C466/40/01-08 Digitised from cassette originals Collection title: Artists’ Lives Interviewee’s surname: Kidner Title: Interviewee’s forename: Michael Sex: Male Occupation: Dates: 1917 Dates of recording: 16.3.1996, 29.3.1996, 4.8.1996 Location of interview: Interviewee’s home Name of interviewer: Penelope Curtis and Cathy Courtney Type of recorder: Marantz CP430 and two lapel mics Recording format: TDK C60 Cassettes F numbers of playback cassettes: F5079-F5085, F5449 Total no. -

Feb 2 7 2004 Libraries Rotch

Architecture Theory 1960-1980. Emergence of a Computational Perspective by Altino Joso Magalhses Rocha Licenciatura in Architecture FAUTL, Lisbon (1992) M.Sc. in Advanced Architectural Design The Graduate School of Architecture Planning and Preservation Columbia University, New York. USA (1995) Submitted to the Department of Architecture, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture: Design and Computation at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY OF TECHNOLOGY February 2004 FEB 2 7 2004 @2004 Altino Joso Magalhaes Rocha All rights reserved LIBRARIES The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of Author......... Department of Architecture January 9, 2004 Ce rtifie d by ........................................ .... .... ..... ... William J. Mitchell Professor of Architecture ana Media Arts and Sciences Thesis Supervisor 0% A A Accepted by................................... .Stanford Anderson Chairman, Departmental Committee on Graduate Students Head, Department of Architecture ROTCH Doctoral Committee William J. Mitchell Professor of Architecture and Media Arts and Sciences George Stiny Professor of Design and Computation Michael Hays Eliot Noyes Professor of Architectural Theory at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design Architecture Theory 1960-1980. Emergence of a Computational Perspective by Altino Joao de Magalhaes Rocha Submitted to the Department of Architecture on January 9, 2004 in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture: Design and Computation Abstract This thesis attempts to clarify the need for an appreciation of architecture theory within a computational architectural domain. It reveals and reflects upon some of the cultural, historical and technological contexts that influenced the emergence of a computational practice in architecture. -

Art and Analysis

ART AND ANALYSIS AN ADRIAN STOKES READER Edited by Meg Harris Williams Published for The Harris Meltzer Trust by KARNAC COlVIE/V15 Published in 2014 for The Harris Meltzer Tiust by Karnac Boola Ltd, I 18 Finchley Road, London N!73 5HT selections from rhe wrirings ofAdrian Stokes reprinted from the original editions end' The criticalrr/ritings ofAdrian stohesby permission of The Adria¡r Stokes Estate. Copi'right @ 1978 The Adrian Stokes Estate Arrangement and introducdon @ 2014 Meg Harris'Williams Appendix 1 @ The Ha¡ris Meløer Tiust Appendix2@EricRhode Acknowledgements vll Cover illustrari on. Landscape, West Pentaith Moor (1937) by Adrian Stokes (1902-1972) @ The Adria¡ Stokes Estate. Acquired byTäte 1985. About the authors ix Photo @ Tate, London 2014 lntroduction by Meg Harris'!7'illiams xi The rights ofAdrian Stokes a¡rd Meg Harris \Øilliams to be identiÊed as aurhors of this work have been asserted in accordance with SS 77 and78 of the Copyright Design and Patents.{cr 1988. , 1 The quest for sanity 1 The arts of life 1 AJI rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a ¡etrieval system, or trensmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, The power to communicate 2 mecha¡rical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written Relating to the object (with Donald Meltzer) 4 permission of the publisher. Inner truth and outer space 8 The image of British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data saniry l0 A C.I.P for this book is available from t}te British Library Form and wholeness T4 Contemplative srares r5 ISBN 978 r 78220 tt9 2 Edited, designed and produced by The Bourne Studios 2 Art and the inner world 27 www.bournestudios. -

Published in January 2020

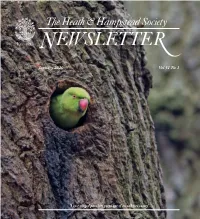

The Heath & Hampstead Society January 2020 Vol 51 No 1 Captions - to be OUTSIDE image boxes unless stated ‘A rose-ringed parakeet peeps out of an oak tree cavity’ Contents Chair’s Notes Page by Marc Hutchinson Chair’s Notes by Marc Hutchinson . 1 Christmas party Should we be nervous of trees? . 3 We welcomed a record number of guests, including Heath Report by John Beyer . 4 senior Heath managers from the City, to last year's Christmas Party at Burgh House, and everyone had a To w n R e p o r t by Andrew Haslam-Jones . 6 most enjoyable evening. Planning Report by David Castle . 8 South Fairground Site Springett Lecture 2019 – Bird Navigation: How do The owner and builder of the illegal house has pigeons find their way home? by Dr Rupert Sheldrake . 10 demolished it, following her decision not to appeal the ruling of the planning inspector to the High Court. Annual General Meeting 2020 . 14 We wait to see to what lawful use the site may now proposed to be put. Alien Species on the Heath by Jeff Waage . 15 How Hampstead Heath Was Saved . 20 Hampstead Police Station by Andrew Neale . 21 A Magical Space by Emilia A. Leese . 24 Photographic Competition #myhampsteadheath . 26 Appeal to Members . 26 Camden Arts Centre Events . 27 South Fairground Site; demolition of Bren Cottage. Spring 2020 Events in the Library . 28 Burgh House & Hampstead Museum Events . 29 North Fairground Site Heath Walks: 2020 . 30 The final day of this twice-adjourned Planning Inquiry was 18 December 2019. -

Today': Stokes, Pound, Freud and the Word-Image Opposition

Today': Stokes, Pound, Freud and the word-image opposition RICHARD READ The subtle, difficult and neglected English twentieth- end result of a necessarily incomplete synthesis of con- century art critic Adrian Stokes developed a complex and tending intellectual counter-currents whose turbulence, for original if somewhat eccentric 'semiotic' theory of the some of his perceptive but unsympathetic early reviewers, relationship between words and images by synthesizing still showed through the calm of his final effects. two antithetical authorities: Ezra Pound and Sigmund G. Price:Jones, for example, a reviewer of Stokes's Freud. My interest in pointing to these sources has a Colour and Form (1937) in the Burlington Magazine, employed twofold 'agenda'. One is the resemblance between Stokes's a fastidiously classical style to make dry humour out of visual-verbal theory and contemporary theoretical interest the dichotomy between the classical certainty of Stokes's in the relationship between semiosis and semiotics, where spatialized visions and the subjective manner in which semiosis represents attention to the turbulent process of they were expressed: making and interpreting texts and images while semiotics A certain spirality of mind, operating almost always amid represents the analysis of their objective and assumedly the most delicate nuances of private perceptions, oblique unmediated structures. Michael O'Toole has made a clear angles and subjectively apocalyptic insights, makes it difficult and helpful distinction between them: to follow with confidence arguments which meander tantal- Semiosis, a term foregrounded by C. S. Peirce, shifts izingly between the planes of abstract and concrete attention from the text of a semiotic message to the interpret- discourse.4 ative process whereby the listener or reader or viewer The confusion identified here is that of an undisciplined interprets the range of possible meanings that are embodied mind that spirals haplessly between planes of philosophical in the text. -

Appendix I Artist’S Biographies

Appendix I Artist’s Biographies Note: biographies on Karl Weschke, Grayson Perry, Bernard Leach and Ged Quinn are included within the teachers’ notes. Ralph Brown (born 1928) English sculptor. Studied at Leeds School of Art (1948-51), Hammersmith School of Art (1951-2) and the Royal College of Art (1952-6). In the 1950s he made visits to Paris and Italy studying the work of Rodin and Medardo Rosso as well as Etruscan sculpture and early renaissance painting. Made contact with Ossip Zadkine, Richier, Giacometti, Marino Marini and Picasso. He taught at the Royal College from 1956-73 and was elected a Royal Academician in 1972. His sculpture has focused on the figurative tradition and is characterised by robust modelling and either savage imagery or gentle erotic forms. He has exhibited widely and in 1988 he had a major retrospective exhibition at the Henry Moore Centre. Max Beckmann (1884-1950) German-born painter. Studied at the Weimar Academy but also spent time in Paris 1903-4. First one-man exhibition in Frankfurt in 1911. In 1914 he joined as a medical orderly bit was discharged in 1915 after a breakdown. He was appointed to teach at the Städel School in Frankfurt in 1925. Beckmann’s early work focused on naturalistic portraits and history paintings. The experience of war led him to paint a series of religious and contemporary scenes in a more ‘expressionist’ style. Dismissed from his teaching post by the Nazis, Beckmann left Germany in 1937, settling first in Amsterdam before emigrating to America. In 1950 he was awarded First Prize for Painting at the Venice Biennale. -

Kettle's Yard

KETTLE’S YARD: ANTI-MUSEUM H.S. Ede, modernism and the experience of art Elizabeth Anne Fisher Clare College October 2018 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy DECLARATION This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. It is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University of similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It does not exceed the prescribed word limit of 80,000 words. 2 ABSTRACT This thesis attempts to tackle the question of what is, or more precisely, what was Kettle’s Yard, by exploring the intellectual origins of the institution initially conceived and developed by H.S. Ede. Ede bought Kettle’s Yard in 1956, and began to welcome visitors into his home in 1957. As a private initiative, Kettle’s Yard promoted an unusually intimate encounter with art. Following its transferral to the University of Cambridge in 1968, Kettle’s Yard still offered a qualitatively different experience to that of a conventional museum. -

Modern British Art

PRESS RELEASE N E W C O N N E C T I O N S: MODERN BRITISH ART Exhibition: Saturday 16 April – Sunday 19 June 2011 Private View: Friday 15 April 6 – 8pm Mottisfont Abbey, one of Hampshire’s oldest historic houses, is revisiting its links with the Modern British art scene with a new exhibition that has seen a hitherto private floor of the house transformed into a contemporary exhibition space. The first exhibition, New Connections: Modern British Art, showcases selected works from Mottisfont’s Derek Hill Collection, alongside significant loans from Austin / Desmond Fine Art, London, a selection of which will be for sale. The exhibition explores the personal and professional connections between Hill and his contemporaries, and identifies some of the key themes of this period of Modernism in Britain. The early 20th-century was a time of extraordinary creativity for the arts in Britain. Arts patron and society hostess Maud Russell embraced this movement and turned her home, Mottisfont near Romsey, into a vibrant hub of artistic activity. One of Maud’s great friendships was with the renowned portraitist and landscape artist Derek Hill (1916- 2000), who was born near Southampton and brought up at nearby Broadlands. Hill was a friend and advisor to many of the most influential artists of the day, whose work he also collected, some of which he later bequeathed to Mottisfont. New Connections will introduce the theme of ‘outsider art’ with a focus on the first generation of self- taught painters from Tory Island (off the North West Irish coast), amongst them James Dixon and his direct association with Derek Hill. -

This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from the King's Research Portal At

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ IMAGE OF A MAN Self-construction in the Journal of Keith Vaughan Belsey, Alex Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 28. Sep. 2021 1 IMAGE OF A MAN Self-construction in the Journal of Keith Vaughan ALEX BELSEY King’s College London Thesis submitted to the University of London for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2015 2 Abstract The British painter Keith Vaughan (1912-77) spent his career studying the male figure and its relationship to its environment. -

A Biographical Note on Adrian Stokes by Donald Meltzer1

A biographical note on Adrian Stokes by Donald Meltzer1 On 15 December 1972, in a lovely Georgian terraced house in Church Row, the most beautiful street in Hampstead, the country playground of Eighteenth Century London, Adrian Stokes (1902–1972) died quietly and with great dignity, painting to the very last despite the impairment from brain metastases of a rectal carcinoma. His life was both a private and a public one of unflagging devotion to art and to psychoanalysis—and to building a bridge between the two that will stand for generations. Mr. Stokes, as he came to be respectfully called by all his admirers save the few most intimate, was born in London and educated at Rugby and Magdalen College, Oxford. Handsome and sociable, a superb tennis player and gifted speaker, his life was equally divided between the schol- arship of art history, painting, and participation in the worlds of art and psychoanalysis. He numbered many of the most distinguished figures of both worlds among his personal friends: Ezra Pound, Naum Gabo, D. H. Lawrence, Roger Money-Kyrle, Ben Nicholson, Barbara Hepworth, and many, many others. He served the Tate Gallery for several years and saved the work of the Cornish primitive, Alfred Wallis, from destruction at the time of the artist’s death in poverty and obscurity. He was among the first patients of Melanie Klein when she came to England, and this experience coloured his life and activities thereafter. In 1950, with the musician Rob- ert Still, he founded the Imago Society of London. However, painting and writing about art were his two main profes- sional activities.