Proc for Pdf Making

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography and Scientific Name Index to Amphibians

lb BIBLIOGRAPHY AND SCIENTIFIC NAME INDEX TO AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES IN THE PUBLICATIONS OF THE BIOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF WASHINGTON BULLETIN 1-8, 1918-1988 AND PROCEEDINGS 1-100, 1882-1987 fi pp ERNEST A. LINER Houma, Louisiana SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE NO. 92 1992 SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE The SHIS series publishes and distributes translations, bibliographies, indices, and similar items judged useful to individuals interested in the biology of amphibians and reptiles, but unlikely to be published in the normal technical journals. Single copies are distributed free to interested individuals. Libraries, herpetological associations, and research laboratories are invited to exchange their publications with the Division of Amphibians and Reptiles. We wish to encourage individuals to share their bibliographies, translations, etc. with other herpetologists through the SHIS series. If you have such items please contact George Zug for instructions on preparation and submission. Contributors receive 50 free copies. Please address all requests for copies and inquiries to George Zug, Division of Amphibians and Reptiles, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC 20560 USA. Please include a self-addressed mailing label with requests. INTRODUCTION The present alphabetical listing by author (s) covers all papers bearing on herpetology that have appeared in Volume 1-100, 1882-1987, of the Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington and the four numbers of the Bulletin series concerning reference to amphibians and reptiles. From Volume 1 through 82 (in part) , the articles were issued as separates with only the volume number, page numbers and year printed on each. Articles in Volume 82 (in part) through 89 were issued with volume number, article number, page numbers and year. -

(Research Project) เรื่อง ความผันแปรของรูปแบ

ก รายงานวิจัย (Research Project) เรื่อง ความผันแปรของรูปแบบลวดลายลำตัวด้านหลังของตุ๊กแกป่าตะวันออก (Intermediate Banded Bent - toed Gecko; Crytodactylus intermedius) ในสถานีวิจัยสิ่งแวดล้อมสะแกราช The variation of dorsa pattern on Intermediate Banded Bent - toed Gecko (Crytodactylus intermedius) in Sakaerat Environmental Station โดย นางสาว ขนิษฐา ภูมิมะนาว สาขาวิทยาศาสตร์สิ่งแวดล้อม คณะวิทยาศาสตร์และเทคโนโลยี มหาวิทยาลัยราชภัฏนครราชสีมา ก บทคัดย่อ สถานีวิจัยสิ่งแวดล้อมสะแกราช เป็นพื้นที่ที่มีความอุดมสมบรูณ์ของชนิดพันธุ์พืชและสัตว์ป่าในระดับสูง ซึ่งสัตว์ป่าที่สำรวจพบในเขตสถานีวิจัยสิ่งแวดล้อมสะแกราช มีทั้งหมดประมาณ 486 ชนิด เป็นสัตว์เลื้อยคลาน จำนวน 92 ชนิด ในจำนวนสัตว์ดังกล่าวเป็นสัตว์หายาก ใกล้สูญพันธุ์และเป็นสัตว์เฉพาะถิ่น ซึ่งหนึ่งในนั้น คือ ตุ๊กแกป่าตะวันออก (Intermediate Banded Bent-toed Gecko; Cyrtodactylus intermedius) งานวิจัยนี้มี วัตถุประสงค์เพื่อศึกษาความผันแปรของตุ๊กแกป่าตะวันออกและเพื่อทดสอบการระบุตัวตนของตุ๊กแกป่าตะวันออก ด้วยวิธีการใช้ภาพถ่ายรูปแบบลวดลายบนลำตัวด้านหลังในบริเวณป่าดิบแล้งในสถานีวิจัยสิ่งแวดล้อมสะแกราช ทำการศึกษาโดยใช้วิธีการสำรวจแบบแนวเส้น (line counting) ตามเส้นทางการสำรวจทั้งหมด 3 เส้นทาง คือ เส้นทางการเดินป่าศึกษาธรรมชาติหลักแดง เส้นแนวกันไฟที่ 6 และเส้นทางการเดินป่าศึกษาธรรมชาติหอคอยที่ 2 พบว่า สามารถจัดกลุ่มตัวอย่างตุ๊กแกป่าตะวันออกได้โดยอาศัยรูปแบบลวดลายลำตัวด้านหลัง ได้ดังนี้ ส่วนหัว แบ่งเป็น 2 รูปแบบ คือ รูปตัวยูและรูปตัววี ส่วนลำตัวด้านหลังแบ่งเป็น 6 รูปแบบ คือ แถบดำขวางบริเวณลำตัว 5 แถบ แถบดำขวางบริเวณลำตัว 4 แถบ แถบดำขวางบริเวณลำตัว 5 แถบ มีลายขาด แถบดำขวางบริเวณลำตัว 5 แถบ ไม่มีลายขาด แถบดำขวางบริเวณลำตัว -

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History Database

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History database Abdala, C. S., A. S. Quinteros, and R. E. Espinoza. 2008. Two new species of Liolaemus (Iguania: Liolaemidae) from the puna of northwestern Argentina. Herpetologica 64:458-471. Abdala, C. S., D. Baldo, R. A. Juárez, and R. E. Espinoza. 2016. The first parthenogenetic pleurodont Iguanian: a new all-female Liolaemus (Squamata: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. Copeia 104:487-497. Abdala, C. S., J. C. Acosta, M. R. Cabrera, H. J. Villaviciencio, and J. Marinero. 2009. A new Andean Liolaemus of the L. montanus series (Squamata: Iguania: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. South American Journal of Herpetology 4:91-102. Abdala, C. S., J. L. Acosta, J. C. Acosta, B. B. Alvarez, F. Arias, L. J. Avila, . S. M. Zalba. 2012. Categorización del estado de conservación de las lagartijas y anfisbenas de la República Argentina. Cuadernos de Herpetologia 26 (Suppl. 1):215-248. Abell, A. J. 1999. Male-female spacing patterns in the lizard, Sceloporus virgatus. Amphibia-Reptilia 20:185-194. Abts, M. L. 1987. Environment and variation in life history traits of the Chuckwalla, Sauromalus obesus. Ecological Monographs 57:215-232. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2003. Anfibios y reptiles del Uruguay. Montevideo, Uruguay: Facultad de Ciencias. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2007. Anfibio y reptiles del Uruguay, 3rd edn. Montevideo, Uruguay: Serie Fauna 1. Ackermann, T. 2006. Schreibers Glatkopfleguan Leiocephalus schreibersii. Munich, Germany: Natur und Tier. Ackley, J. W., P. J. Muelleman, R. E. Carter, R. W. Henderson, and R. Powell. 2009. A rapid assessment of herpetofaunal diversity in variously altered habitats on Dominica. -

References Monito Gecko Final Delisting Rule Case, T.J. and D.T. Bolger. 1991. the Role of Introduced Species in Shaping The

References Monito gecko Final Delisting Rule Case, T.J. and D.T. Bolger. 1991. The role of introduced species in shaping the distribution and abundance of island reptiles. Evolutionary Ecology 5: 272-290. Dodd, C.K., Jr. 1985. Reptilia: Squamata: Sauria: Gekkonidae, Sphaerodactylus micropithecus. Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles, 363: 1-2. Dodd, C.K., Jr. and P.R. Ortiz. 1983. An endemic gecko in the Caribbean. Oryx 17: 119- 121. Dodd C.K., Jr. and P.R. Ortiz. 1984. Variation of dorsal pattern and scale counts in the Monito gecko, Sphaerodactylus micropithecus. Copeia (3): 768-770. Ewel, J.J. and J.L. Whitmore. 1973. The ecological life zones of Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. U.S. Forest Service Res. Pap. ITF 18: 72 pp. García, M.A., C.E. Diez, and A.O. Alvarez. 2002. The eradication of Rattus rattus from Monito Island, West Indies. Pages 116-119 in, Turning the tide: the eradication of invasive species: Proceedings of the International Conference on Eradication of Island Invasives. Veitch, C.R. and M.N. Clout, (eds.). Occasional Paper of the International Conference on Eradication of Island Invasives No. 27. Hammerson, G.A. 1984. Monito Gecko survey. Department of Natural and Environmental Resources. San Juan, PR. 3 pp. Island Conservation (IC). 2016. Population Status of the Monito Gecko. Report submitted to the USFWS Caribbean Ecological Services Field Office. Cooperative Agreement No. F15AC00793. Boquerón, PR. 14 pp. Jones, H.P., N.D. Holmes, S.H.M Butchart, B.R. Tershy, P.J. Kappes, I. Corkery, A. Aguirre-Muñoz, D.P. -

State of Nearshore Marine Habitats in the Wider Caribbean

UNITED NATIONS EP Distr. LIMITED UNEP(DEPI)/CAR WG.42/INF.5 1 February 2021 Original: ENGLISH Ninth Meeting of the Scientific and Technical Advisory Committee (STAC) to the Protocol Concerning Specially Protected Areas and Wildlife (SPAW) in the Wider Caribbean Region 17–19 March 2021 THE STATE OF NEARSHORE MARINE HABITATS IN THE WIDER CARIBBEAN For reasons of public health and safety associated with COVD-19, this meeting is being convened virtually. Delegates are kindly requested to access all meeting documents electronically for download as necessary. *This document has been reproduced without formal editing. 2020 The State of Nearshore Marine Habitats in the Wider Caribbean United Nations Environment Programme - Caribbean Environment Programme (UNEP-CEP) Caribbean Natural Resources Institute (CANARI), Technical Report No. 00 Title of the Report Authors of the Report Partner’s Name, Technical Report No.00 Catalyzing implementation of the Strategic Action Programme for the Caribbean and North Brazil Shelf LME’s (2015-2020) ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Development of this Information Product and its contents, and/or the activities leading thereto, have benefited from the financial support of the UNDP/GEF Project: “Catalysing Implementation of the Strategic Action Programme (SAP) for the Sustainable Management of shared Living Marine Resources in the Caribbean and North Brazil Shelf Large Marine Ecosystems” (CLME+ Project, 2015-2020) The CLME+ Project is executed by the United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS) in close collaboration with a large number of global, regional and national-level partners. All are jointly referred to as the “CLME+ Project co- executing partners”. www.clmeproject.org [email protected] As a GEF Agency, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) implements a global portfolio of GEF co-funded Large Marine Ecosystem projects, among which the CLME+ Project. -

Guide to Theecological Systemsof Puerto Rico

United States Department of Agriculture Guide to the Forest Service Ecological Systems International Institute of Tropical Forestry of Puerto Rico General Technical Report IITF-GTR-35 June 2009 Gary L. Miller and Ariel E. Lugo The Forest Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture is dedicated to the principle of multiple use management of the Nation’s forest resources for sustained yields of wood, water, forage, wildlife, and recreation. Through forestry research, cooperation with the States and private forest owners, and management of the National Forests and national grasslands, it strives—as directed by Congress—to provide increasingly greater service to a growing Nation. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD).To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W. Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Authors Gary L. Miller is a professor, University of North Carolina, Environmental Studies, One University Heights, Asheville, NC 28804-3299. -

United Nations Environment Programme

UNITED NATIONS EP Distr. LIMITED United Nations Environment UNEP(DEPI)/CAR WG.38/4 26 September 2016 Programme Original: ENGLISH Seventh Meeting of the Scientific and Technical Advisory Committee (STAC) to the Protocol Concerning Specially Protected Areas and Wildlife (SPAW) in the Wider Caribbean Region Miami, Florida, 2 ‐ 4 November 2016 REPORT OF THE WORKING GROUP ON THE APPLICATION OF CRITERIA FOR LISTING OF SPECIES UNDER THE ANNEXES TO THE SPAW PROTOCOL (INCLUDES SPECIES PROPOSED FOR LISTING IN ANNEXES II and III) TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. Background.......................…………..................................…………………………………………….…….. 1 II. Annotated list of species recommended for inclusion on the SPAW Annexes ………………………............. 2 Appendix 1: Revised Criteria and Procedure for the Listing of Species in the Annexes of the SPAW Protocol ...... 4 Appendix 2: Annexes of the SPAW Protocol Revised (2016)………………………………………………….........6 UNEP(DEPI)/CAR WG.38/4 Page 1 REPORT OF THE WORKING GROUP ON THE APPLICATION OF CRITERIA FOR LISTING OF SPECIES UNDER THE ANNEXES TO THE SPAW PROTOCOL (INCLUDES SPECIES PROPOSED FOR LISTING IN ANNEXES II and III) I. Background At the Third Meeting of the Contracting Parties (COP 3) to the Protocol Concerning Specially Protected Areas and Wildlife (SPAW) in the Wider Caribbean Region, held in Montego Bay, Jamaica, September 27, 2004, the Parties approved the Revised Criteria for the Listing of Species in the Annexes of the SPAW Protocol and the Procedure for the submission and approval of nominations of species for inclusion in or deletion from Annexes I, II and III. At the 6th Meeting of the Scientific and Technical Advisory Committee (STAC6) and 8th Meeting of the Contracting Parties (COP8) to the SPAW Protocol held in Cartagena, Colombia, 8 and 9 December 2014 respectively, the procedure for listing was further revised by Parties using Article 11(4) as a basis and the existing approved Guidelines and Criteria (see Appendix 1 to this report). -

0363 Sphaerodactylus Micropit

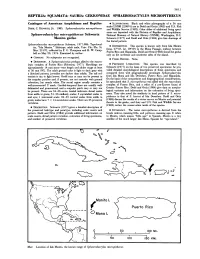

363.1 REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: SAURIA: GEKKONIDAE SPHAERODACfYLUS MICROPITHECUS Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. • ILLUSTRATIONS. Black and white photographs of a 36 mm male (USNM 229891) are in Dodd and Ortiz (1983) and U.S. Fish DODD, C. KENNETH, JR. 1985. Sphaerodactylus micropithecus. and Wildlife Service (1982). Color slides of additional living speci• mens are deposited with the Division of Reptiles and Amphibians, Sphaerodactylus micropithecus Schwartz National Museum of Natural History (USNM), Washington, D.C. Monito gecko Schwartz (1977) and Dodd and Ortiz (1984) give line drawings of the dorsal pattern. Sphaerodactylus micropithecus Schwartz, 1977 :986. Type-local• • DISTRIBUTION. This species is known only from Isla Monito ity, "Isla Monito." Holotype, adult male, Univ. Fla.lFla. St. (long. 67°10', lat. 18°10') in the Mona Passage, midway between Mus. 21570, collected by F. G. Thompson and H. W. Camp• Puerto Rico and Hispaniola. Dodd and Ortiz (1983) found the gecko bell on May 20, 1974. Examined by author. only on the northeast and southwest sides of the island. • CONTENT. No subspecies are recognized. • FOSSIL RECORD. None. • DEFINITION. A Sphaerodactylus perhaps allied to the macro• lepis complex of Puerto Rico (Schwartz, 1977). Hatchlings are • PERTINENT LITERATURE. This species was described by approximately 14 mm snout-vent length and adults range at least Schwartz (1977) on the basis of two preserved specimens; he pro• to 36 rom SVL. The adult ground color is light to dark gray with vided detailed morphological descriptions of these specimens and a blotched pattern; juveniles are darker than adults. The tail col• compared them with geographically proximate Sphaerodactylus oration is tan to light brown. -

The State of Nearshore Marine Habitats in the Wider Caribbean

2020 The State of Nearshore Marine Habitats in the Wider Caribbean United Nations Environment Programme - Caribbean Environment Programme (UNEP-CEP) Caribbean Natural Resources Institute (CANARI), Technical Report No. 00 Title of the Report Authors of the Report Partner’s Name, Technical Report No.00 Catalyzing implementation of the Strategic Action Programme for the Caribbean and North Brazil Shelf LME’s (2015-2020) ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Development of this Information Product and its contents, and/or the activities leading thereto, have benefited from the financial support of the UNDP/GEF Project: “Catalysing Implementation of the Strategic Action Programme (SAP) for the Sustainable Management of shared Living Marine Resources in the Caribbean and North Brazil Shelf Large Marine Ecosystems” (CLME+ Project, 2015-2020) The CLME+ Project is executed by the United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS) in close collaboration with a large number of global, regional and national-level partners. All are jointly referred to as the “CLME+ Project co- executing partners”. www.clmeproject.org [email protected] As a GEF Agency, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) implements a global portfolio of GEF co-funded Large Marine Ecosystem projects, among which the CLME+ Project. www.undp.org Through the International Waters (IW) focal area, the Global Environment Facility (GEF) helps countries jointly manage their transboundary surface water basins, groundwater basins, and coastal and marine ecosystems. www.thegef.org UNOPS mission is to serve people in need by expanding the ability of the United Nations, governments and other partners to manage projects, infrastructure and procurement in a sustainable and efficient manner. www.unops.org _______________________ CLME+ Project Information Products are available on the CLME+ Hub (www.clmeplus.org) and can be downloaded free of cost. -

REPTILES and AMPHIBIANS MONITO GECKO ABOUT the Monito Gecko (Sphaeroclactylus Micropithecus) Is a Lizard That Only Grows to A

REPTILES AND AMPHIBIANS MONITO GECKO ABOUT The Monito Gecko (Sphaeroclactylus Micropithecus) is a lizard that only grows to about l.5 in (3.5 cm) and they weigh less than 0.01oz (0.1g). They are usually pale tan in color, with scattered dark brown scales. This species has a small, flat body with short legs and a head that appears too large for its body. The Monito Gecko makes a variety of noises – squeaking, croaking and an unusual bark. Young Monitos are darker than the adults and the tails are always lighter than the body. As a defensive mechanism geckos can lose their tails, but they always grow back. They have toe pads that expand and their tiny suction cup-like bristles enable them to climb walls and move over smooth surfaces. Because their habitat, Monito Island, is so difficult to get to most of the year, little is known about this gecko’s lifespan, feeding or breeding habits. It is believed that females lay 1 or 2 eggs that take 2-3 months to hatch and also that the reproductive season lasts from March to November. It is likely that, like most lizards, they feed on insects and little bugs. DID YOU KNOW? The Monito Gecko was discovered in 1974. It was listed as endangered in 1982 and one of the reasons this may be so is that the island they live on, between Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic, was used as a bombing range by the United States army during World War II, destroying much of the habitat. -

SERDP Project ER18-1653

FINAL REPORT Approach for Assessing PFAS Risk to Threatened and Endangered Species SERDP Project ER18-1653 MARCH 2020 Craig Divine, Ph.D. Jean Zodrow, Ph.D. Meredith Frenchmeyer Katie Dally Erin Osborn, Ph.D. Paul Anderson, Ph.D. Arcadis US Inc. Distribution Statement A Page Intentionally Left Blank This report was prepared under contract to the Department of Defense Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program (SERDP). The publication of this report does not indicate endorsement by the Department of Defense, nor should the contents be construed as reflecting the official policy or position of the Department of Defense. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the Department of Defense. Page Intentionally Left Blank Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 The public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing the burden, to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. -

Report on Legislation by the Animal Law Committee S. 1863

CONTACT POLICY DEPARTMENT MARIA CILENTI 212.382.6655 | [email protected] ELIZABETH KOCIENDA 212.382.4788 | [email protected] REPORT ON LEGISLATION BY THE ANIMAL LAW COMMITTEE S. 1863 Sen. Lee To clarify that noncommercial species found entirely within the borders of a single State are not in interstate commerce or subject to regulation under the Endangered Species Act of 1973 or any other provision of law enacted as an exercise of the power of Congress to regulate interstate commerce. Native Species Protection Act THIS LEGISLATION IS OPPOSED I. SUMMARY OF PROPOSED LAW The Native Species Protection Act (the “Bill”) would remove “intrastate species” from the scope of the Endangered Species Act (“ESA”) of 1973, or any other provision of law under which regulatory authority is based on the power of Congress to regulate interstate commerce under the Commerce Clause. The Bill defines an “intrastate species” as any species of plant or fish or wildlife that is found entirely within the borders of a single state1 and that is not part of a national market for any commodity.2 Despite its name, the Native Species Protection Act does not protect native species; instead, by undermining the protections of the ESA, it puts these species at risk. If the Bill passes, roughly 50 animal species that exist purely within one state,3 such as the Nashville crayfish and the Utah prairie dog, 4 will no longer be protected by the ESA. 1 The ESA defines “State” as “any of the several States, the District of Columbia, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, American Samoa, the Virgin Islands, Guam, and the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands.” 16 U.S.