Narrative Expressions of the Feminine Divine in the Devīpurāṇa James F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ward No: 105 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79

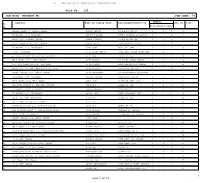

BPL LIST-KOLKATA MUNICIPAL CORPORATION Ward No: 105 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79 Member Sl Address Name of Family Head Son/Daughter/Wife of BPL ID Year No Male Female Total 1 RAMLAL BAZAR 50 RAMLAL BAZAR AARATI GHOSH LT.PARESH GHOSH 2 3 5 1 2 JADAVGARH 1/59 JADAVGARH ABHIJIT MONDAL LATE GOURANGA CH MONDAL 3 1 4 2 3 HALTU 2/30 SUCHETA NAGAR ADHAR SADDAR LT BIPIN SADDAR 1 1 2 3 4 SAHID NAGAR 8/22 SAHID NAGAR ADHIR DUTTA LATE ABINASH DUTTA 1 3 4 4 5 JADAVGARH 3/50 JADAVGARH AJAY SAHA AKUL CH. SAHA 1 2 3 6 6 8/20 JADAVGARH AJIT CHAKROBARTY LATE ANIL KUMAR CHAKROBAR 3 2 5 7 7 ASHUTOSH COLONY 40 ASHUTOSH COLONY AJIT DAS JIBAN CH DAS 3 1 4 8 8 NELI NAGAR 2/157 NELI NAGAR AJIT MANDAL LT RADHA RAMAN MANDAL 3 2 5 9 9 K.P. ROY LANE 10A K.P. ROY LANE AJIT SARKAR LATE MAKHAN LAL SARKAR 2 1 3 10 10 GARFA VAIDYA PARA GARFA VAIDYA PARA ALOK BAIDYA LATE AJIT BAIDYA 3 1 4 11 11 SHAHID NAGAR 8/10 SHAHID NAGAR ALOK CHOUDHURY LT ACHALANANDA CHOUDHURY 1 1 2 12 12 JADAVGARH 3/65 JADAVGARH ALPANA SIKDAR LATE ASIT SIKDAR 2 1 3 13 13 NELI NAGAR 4/44 NELI NAGAR AMAL SHIL SURENDRA NATH SHIL 3 2 5 15 14 ASHUTOSH COLONY 13 ASHUTOSH COLONY AMAR DAS HAREN CH DAS 2 2 4 16 15 JADAVGARH 3/17B JADAVGARH AMIRON MONDAL IMON MONDAL 0 3 3 17 16 JADAVGARH 3/31 JADAVGARH AMIYA PAUL LATE KALACHAND PAUL 6 6 10+ 18 17 HALTU 11 HALTU MAIN ROAD ANIL DAS SUREN CH DAS 2 3 5 19 18 NELI NAGAR 2/159 NELI NAGAR ANIL DAS 3 1 4 20 19 ASHUTOSH COLONY 44A ASHUTOSH COLONY ANIL DAS MEKHU CH DAS 1 1 2 21 20 RAM KRISHNA PALLY 37 RAM KRISHNA PALLY ANIL MANDAL NARAYAN CH MANDAL 2 1 3 23 21 HALTU 3/56 JADAVGARH ANIL SARKAR LT MAKHAN LAL SARKAR 3 4 7 24 22 SHAHID NAGAR 8/34 SHAHID NAGAR ANIL SHAW 2 2 4 25 23 ASHUTOSH COLONY 91 ASHUTOSH COLONY ANITA DAS GURUDAS DAS 1 3 4 26 24 NELI NAGAR 1/18 NELI NAGAR ANITA MISTRI RAMESH MISTRI 1 1 2 27 25 DHAKURIA EAST ROAD 25/3 DHAKURIA EAST ROAD ANITA PAUL LATE BIMAL PAUL 2 1 3 28 26 SAHID NAGAR 8/2 SAHID NAGAR ANIYA BALA BASU LT BHUPENDRA KR. -

Ph.D. Regulation 2017

JADAVPUR UNIVERSITY PH.D. REGULATION 2017 Provisions relating to Doctorate Degree The following Amendments to the Ph.D. Regulations 2010 of Jadavpur University, in consonance with UGC M.Phil / Ph.D Regulations 2016, shall be applicable to all Ph.D. programmes offered by the university, and to the Ph.D. programmes offered by other institutes that are recognized by and affiliated to Jadavpur University, with effect from May 16, 2017. Award of degrees to candidates registered for the Ph.D. programme on or after July 11, 2009, but before May 16, 2017, shall be governed by the Ph.D. Regulations 2010 of Jadavpur University that were adopted in consonance with provisions of the UGC (Minimum Standards and procedure for Awards of Ph.D Degree) Regulation, 2009. 17. The University will award the following Doctorate Degrees: i) D.Litt. in Arts; D.Sc. in Science, Engineering & Technology / Pharmacy ii) Ph.D. (Arts); Ph.D. (Science); Ph.D. (Engg. / Pharm.) in Arts, Science and Engineering & Technology / Pharmacy respectively. Of the above two categories, the degree of D.Litt. & D.Sc. are to be considered as Doctorate Degrees of higher level and no supervisory guidance will be necessary. Supervisory guidance is compulsory for Ph.D. degrees in all disciplines except as provided in clause 23, below. Ph.D. Programme shall be of a minimum duration of three years including course work and maximum six years with one year extension subject to clause 19(v) below. Female candidates and candidates having at least 40% disability may be granted further extensions beyond this limit as per Clause 19(v). -

1 CURRICULUM VITAE Partha Chatterjee Date of Birth

1 CURRICULUM VITAE Partha Chatterjee Date of birth: November 5, 1947 Permanent address: 41B Garcha Road, Calcutta 700019, India Address in United States: 456 Riverside Drive, Apt. 5B, New York, NY 10027 E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Present positions: Honorary Professor of Political Science, Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta, R1 Baishnabghata Patuli Township, Kolkata 700094, India Professor of Anthropology, Columbia University, Professor of Middle Eastern, South Asian and African Studies, Columbia University, And Member, Committee on Global Thought, Columbia University, New York 10027, USA. Academic Career 1967 B. A. with First Class Honours in Political Science, University of Calcutta. 1970 M. A. in Political Science, University of Rochester, Rochester, New York. 1971-72 Ph. D. in Political Science, University of Rochester, Rochester, New York. Professional Career 1971-72 Assistant Professor of Political Science, University of Rochester. 1972 Assistant Professor of Political Science, Presidency College, Calcutta. 1972-73 Reader in Political Science, Guru Nanak University, Amritsar. 1973-79 Fellow, Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta. 1979- 2009 Professor of Political Science, Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta. 1997-present Professor of Anthropology, Columbia University, New York 2 1997- 2007 Director, Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta 2006-present Member, Committee on Global Thought, Columbia University, New York 2007-present Professor, Department of Middle Eastern, South Asian and African Studies, Columbia University, New York 2009-present Honorary Professor of Political Science, Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta Visiting Appointments 1976-78 Visiting Lecturer, Indian Institute of Management, Calcutta. 3 1981-82 Visiting Fellow, St Antony's College, Oxford. -

62/9, Haripada Dutta Lane, Tollygunge, Kolkata- 700033

JADAVPUR EXECUTIVES SRL NAME DESIGNATION D.O.B AREA TELE. NO(R) Residential address Year 1 ACHYUTANANDA MANDAL DY. AREA MANAGER 06.01.1947 JDP 2402-6973 33/B, NaskarPara Road, P.O- Paschimputiary, Kol-41 2007 /JDP 2 AJAY KUMAR CHAKRABARTI DE/JDV & AM/JDV 01.03.1950 JDV 2425-1425 7, Chittaranjan Park, Flat- B/1, Sankalpa Co-operative, Jadavpur, 2010 Kolkata- 700032 3 AJIT KUMAR DEBNATH AGM / ADMIN / JDV 06.01.1951 JDP 2477-6151 Vill-Manikpur Ghosalpara, P.O-Harinavi, 24 Pgs (S), Kolkata -700148. 2011 4 AMIT KUMAR GUPTA DGM / NWO-JDP,Offg. 02.12.1951 JDV 2346-4646 1/4, Rajendra Banerjee Road, Behala, Kolkata- 700034 2011 5 AMIYA DAS 103223 07.02.1951 JDP 2410-1234 E-32,Kalachand Para,Kamdahari,P.O- Garia, Kol -700084 2011 6 AMIYA SANKAR GUPTA SDE / OFFTG./RLU-21 01.12.1948 JDP 2473-9950 52/A, Bank Colony , P.O- Dhakuria, Kolkata- 700031 2008 7 ANIL CHANDRA BISWAS SDE/OFFTG./CR-II/JDP 02.01.1950 JDP 2431-2100 B/25, Baudipur Road, P.O- Bansdroni, Kolkata- 700070 2010 8 ARUN KUMAR BANERJEE OFFTG/ DE/ RKT / 03.01.1948 JDV 2428-6060 226/5/1, N S C Bose road, Flat No. -03, Kolkata- 700092 2008 EXTL 9 ARUN ROY CHOWDHURY SDE / OFFTG 24.04.1950 JDP 2462-6161 East Balia, Balia Main Road, P.O- Garia, Kolkata- 700084 2010 10 ASHIM KUMAR SENGUPTA J.T.O. 04.01.1949 JDP 2422-5500 62/9, Haripada Dutta Lane, Tollygunge, Kolkata- 2009 700033 11 ASIS KUMAR HALDAR 100847 09.04.1952 JDP 2436-5596 F/154, B. -

Doctor and Hospital List, Kolkata Consular District

Medical Facilities in Kolkata Consular District The following list of hospitals and physicians has been compiled by the American Consulate General, Kolkata. It is not meant to be a complete listing, as there are many competent doctors in the community. Retention on this list does not indicate continued competence but rather a lack of negative comment. The listing does not represent either a guarantee of competence or endorsement by the Department of State or by the American Consulate General in Kolkata. Dialing in India: The country code for India is 91. If you are calling within India, please omit the country code and replace with a ‘0’ for all numbers listed below. Contents Hospitals ............................................................................................................................................................... 4 Apollo Gleneagles Hospitals ...................................................................................................................... 4 B.M. Birla Heart Research Centre ............................................................................................................ 4 B.P. Poddar Hospital & Medical Research Ltd. ................................................................................... 4 Belle Vue Clinic .............................................................................................................................................. 5 Bhagirathi Neotia Woman & Child Care Centre ................................................................................ -

Resume: Dr. Dipayan Dey Contact: Cell Phone – 0091-9903181171; Email: [email protected]

Resume: Dr. Dipayan Dey Contact: Cell phone – 0091-9903181171; Email: [email protected] PROFESSIONAL SYNOPSIS An adept professional with more than a decade of comprehensive experience in tertiary teaching of Plant Ecology and Environmental Science and nearly seventeen years of acumen in environmental research, planning and ecosystem management towards sustainable environment development in global south. Supervising research project on Natural Resource Management; Habitat Evaluation and Restoration Ecology, Strategic Impact Assessment Studies, Biodiversity Indexing, Agricultural Carbon Sequestration, Action Research on Downscaling Climate Impact, Hazard Mitigation, Risk Analysis and Adaptive Mitigation through Community Based Interventions. Commendable exposure in environmental economics and ‘Biorights’ of commons. Expertise in research designing, developing action plan or organizing activities and resolving procedural/ logistical problems as appropriate to the completion timeline of project objectives. An effective communicator with excellent relationship management skills & honed analytical, problem solving & organizational abilities. Possess a flexible & detail oriented attitude. ACADEMIC CREDENTIALS University Courses PhD (Forest Biotechnology) “Physiological Studies on Aspects of Climate Impacts on Ageing in Broadleaf Species of East Bhutan” from T. M Bhagalpur University in 2000-2003. M Phil: Dissertation in “Ecosystem Services and Natural Resource Management in Foothill Forests of Bihar” from T.M. Bhagalpur University, -

Complete List of Venues of West Bengal Civil

PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION, WEST BENGAL 161-A, S. P. MUKHERJEE ROAD, KOLKATA - 700 026 WEST BENGAL CIVIL SERVICE (EXE.) ETC. (PRELI.) EXAMINATION, 2020 Date of Examination : 9TH FEBRUARY, 2020 (SUNDAY) Subject : General Studies Time of Examination : 12:00 NOON TO 2:30 P.M. KOLKATA (NORTH) (01) Sl. Name of the Venues No. of Regd. Candts. Roll Nos. No. DUM DUM ROAD GOVT. SPOND. HIGH SCHOOL FOR GIRLS (H.S.) SUB-CENTRE 'A' 0100001 1 16, DUM DUM ROAD, 300 TO KOLKATA - 700030 0100300 DUM DUM ROAD GOVT. SPOND. HIGH SCHOOL FOR GIRLS (H.S.) SUB-CENTRE 'B' 0100301 2 16, DUM DUM ROAD, 288 TO KOLKATA - 700030 0100588 DUM DUM KUMAR ASUTOSH INSTITUTION (BR.) 0100589 3 6/1, DUM DUM ROAD 600 TO KOLKATA - 700030 0101188 NARAINDAS BANGUR MEMORIAL MULTIPURPOSE SCHOOL 0101189 4 BANGUR AVENUE, BLOCK-D 324 TO KOLKATA - 700055 0101512 DUM DUM AIRPORT HIGH SCHOOL SUB-CENTRE 'A' 0101513 5 NEW QUARTERS RESIDENTIAL COMPLEX, AIRPORT 348 TO KOLKATA - 700052 0101860 DUM DUM AIRPORT HIGH SCHOOL SUB-CENTRE 'B' 0101861 6 NEW QUARTERS RESIDENTIAL COMPLEX, AIRPORT 456 TO KOLKATA - 700052 0102316 MAHARAJA MANINDRA CHANDRA COLLEGE SUB-CENTRE 'A' 0102317 7 20, RAMKANTO BOSE STREET 292 TO KOLKATA - 700003 0102608 MAHARAJA MANINDRA CHANDRA COLLEGE SUB-CENTRE 'B' 0102609 8 20, RAMKANTO BOSE STREET 288 TO KOLKATA - 700003 0102896 MAHARAJA COSSIMBAZAR POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE 0102897 9 3, NANDALAL BOSE LANE 600 TO KOLKATA - 700003 0103496 BETHUNE COLLEGIATE SCHOOL 0103497 10 181, BIDHAN SARANI 504 TO KOLKATA - 700006 0104000 TOWN SCHOOL, CALCUTTA 0104001 11 33, SHYAMPUKUR STREET 396 TO KOLKATA - 700004 0104396 RAGHUMAL ARYA VIDYALAYA 0104397 12 33C, MADAN MITRA LANE 504 TO KOLKATA - 700006 0104900 ARYA KANYA MAHAVIDYALAYA 0104901 13 20, BIDHAN SARANI, 400 TO KOLKATA - 700006 (NEAR SRIMANI MARKET) 0105300 RANI BHABANI SCHOOL 0105301 14 PLOT-1, CIT SCHEME, LXIV, GOA BAGAN 300 TO KOLKATA - 700006 0105600 KHANNA HIGH SCHOOL (H.S.) 0105601 15 9, SHIBKUMAR KHANNA SARANI 588 TO KOLKATA - 700015 0106188 THE PARK INSTITUTION SUB-CENTRE 'A' 0106189 16 12, MOHANLAL STREET, P.O. -

Office of the Executive Engineer Bppd – Ii, E&Am Sector, Kmda 2

OFFICE OF THE EXECUTIVE ENGINEER BPPD – II, E&AM SECTOR, KMDA 2ND FLOOR, KIT MARKET COMPLEX JADAVPUR, KOLKATA – 700032. e -QUOTATION NOTICE Memo no.: 82/EE/BPPD - II/E&AM/KMDA/W-18(Pt.-IV) Date: 26/02/2020 Detailed ‘e’-N.I.Q. NO.: 3/Q/EE/BPPD-II/E&AM/KMDA OF 2019-20 DATED : 26/02/2020 Quotation Reference No.- Executive Engineer, BPPD-II, E&AM sector, KMDA at KIT Market Complex Building (2nd floor), Jadavpur, Kolkata -32 for and on behalf of Kolkata Metropolitan Development Authority (KMDA) invites ON LINE e-QUOTATION in KMDA Form No: 1 from bonafide, reliable and resourceful agency for the following work. Detailed NIQ Proceedings will be as follows: Sl. Earnest Lump Sum Bid Money for NAME OF WORK No. Money TWO years (Excluding all (Rs.) Tax)* 1 Fee for car parking of motorised two wheeler 20, 000/- Both in figures and words. and four wheeler in front of Benubanachhaya Waterpark at Baishnabghata Patuli Township purely on contract basis for the period of two years. Minimum Bid Amount: Rs.4,00,000/- excluding GST. (To be paid in two equal instalment 1st instalment before issuance of work order & 2nd instalment is to be paid 30 days before completion of 1st year.) 1. Intending bidder may download the Quotation documents from the website https://wbtenders.gov.in directly with the help of Digital Signature Certificate. 2. Earnest Money is to be remitted by the Quotationer through e-filling as mentioned in the column 3above through Net- Banking/ RTGS/NEFT in respect of the Tender ID in favour of KMDA. -

JADAVPUR UNIVERSITY CENTRAL LIBRARY Kolkata – 700 032 17.1

JADAVPUR UNIVERSITY CENTRAL LIBRARY Kolkata – 700 032 17.1.2019 It is notified that as per the tender process of Rate Contract (NIQ NO. JU/BT/001/2018, dated. 04/09/2018) approved by the Library Committee Meeting dated 10/10/2018, the following vendors are selected to supply print books to Jadavpur University with the accepted discount stated below: Enlisted Vendors with S.D. participated in Tender and agreed to supply: SLN VENDORS'NAME ADDRESS CATEGORIES DF BDDKS O. 1 Bharat Book Block-GD/15,SEC-111, Salt 1,2,5 Distributors Lake City, Kolkata-7000106. Ph.0336454 2 Lndica Publishers & 7/31,Ansari Road, Darya Ganj, 2,3,5 N71e8w3 /Delhi4007-3618180.002 , Distributors Pvt. Ltd. Ph.01123243027/23242328 3 Overseas Press(I) Pvt. Ltd. 2/4,Ansari Road, Darya Guange, 1,2,3,4,5 New Delhi-110002, Mob.9810012994,011- 43476444. ST 4 Prashant Book Agency 4263/A/3/1 Floor, Ansari 2,3,4,5,6 Road, Darya Ganj, New Delhi- 110002, Ph.01165398961, Mob.9818852025 5 Sahitya Bhawan 14/71,Hospital Road, Agra - 2,3 282003,UP, Mob.8697172389/7697742384 6 Techniz Books 4/12,Kalkaji Exten.,Opp.Of 2,3,4,5 International Nehru Place Kalkaji, New Delhi- 110020,Ph.01126284790/911 7 University Book 79,ChauraRasta,Jaipur- 2,3,4,5 House Pvt. Ltd. 302003,Rajasthan, Mob.9414046753 Enlisted Vendors with S.D. participated in Tender but incapable to supply: SLN VENDORS'NAME ADDRESS CATEGORIES OFBOOKS O. ST 1 ACADEMIA FE-6, IITMARKET (1 FLOOR), 1,2,3,4,5,6, E-Books KHARAGPUR- 721302,Mob.9830282376;7044 082376 2 ACADEMIC INDIA 50/38/14/lH,DHARMATALA 1,2,3,4,5,6 ROAD,KASBA,KOL-700042,Mob. -

16‐06‐20 13 5 Seals Garden Lane Cossipore 700002 1 1

Affected Zone DAYS SINCE Date of reporting of REPORTING Sl No. Address Ward Borough Local area the case 13 5 SEALS GARDEN LANE The premises itself 1 1 1 Cossipore 16‐06‐20 COSSIPORE 700002 14 The affected flat/the 59 Kalicharan Ghosh Rd standalone house 2 kolkata ‐ 700050 West 2 1 Sinthi Bengal India 16‐06‐20 14 The premises itself 21/123 RAJA MANINDRA 3 31 Paikpara ROAD BELGACHIA 700037 16‐06‐20 14 14A BIRPARA LANE The premises itself 4 kolkata ‐ 700030 West 31 Belgachia 16‐06 ‐20 BBlIdiengal India 14 The flat itself A4 6 R D B RD Kolkata ‐ 5 41 Paikpara 700002 West Bengal India 16‐06‐20 14 110/1A COSSIPORE Road The premises itself 6 Kolkata ‐ 700002 West 6 1 Chitpur 16‐06‐20 Bengal India 14 Adjacent common passage of affected hut 14 3 GALIFF STREET 7 7 1 Bagbazar including toilet and BAGHBAZAR 700003 water source of the 16‐06‐20 slum 14 Adjacent common passage of affected hut 14 3 GALIFF STREET 8 7 1 Bagbazar including toilet and BAGHBAZAR 700003 water source of the 16‐06‐20 slum 14 Affected Zone DAYS SINCE Date of reporting of REPORTING Sl No. Address Ward Borough Local area the case 1 RAMKRISHNA LANE The premises itself 9 Kolkata ‐ 700003 West 7 1 Girish Mancha 16‐06‐20 Bengal India 14 The premises itself 4/2/1B KRISHNA RAM BOSE 10 STREET SHYAMPUKUR 10 2 Shyampukur KOLKATA 700004 16‐06‐20 14 T/1D Guru Charan Lane The premises itself 11 Kolkata ‐ 700004 West 10 2 Hatibagan 16‐06‐20 Bengal India 14 Adjacent common 47 1 SHYAMBAZAR STREET passage of affected hut 12 Kolk at a ‐ 700004 W est 10 2 Shyampu kur iilditiltdncluding toilet and -

Ward No: 109 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79

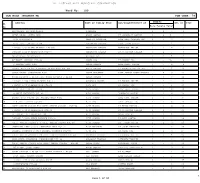

BPL LIST-KOLKATA MUNICIPAL CORPORATION Ward No: 109 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79 Member Sl Address Name of Family Head Son/Daughter/Wife of BPL ID Year No Male Female Total 1 MUKUNDAPUR 100 MUKUNDAPUR A MANDAL 1 2 3 1 2 NITAI NAGAR GREEN PARK ABANI MANDAL LT SANNYASHI MANDAL 6 4 10+ 2 3 2/34 MUKUNDAPUR ABHIJIT ACHARJEE LATE ANIL CHANDRA DAS 2 1 3 3 4 P/13 SOHID SMRITY SADAN ABHIMANNA BAIDYA LATE SHYAM BAIDYA 1 1 2 4 5 D BLOCK D/12 PURBA RAJAPUR D BLOCK ABHIMUNNU HALDER ABHIMUNNU HALDER 2 2 4 5 6 D-BLOCK D/12 PURBARAJAPUR KOL-75 ABHIMUNYA HALDER LT.JUDHISTIR HALDER 3 2 5 6 7 MUKUNDAPUR MUKUNDAPUR ABINASH ROY 3 2 5 7 8 BUDERHAT NAYABAD KOL-99 ADHIR DAS LT.PANCHU DAS 6 5 10+ 8 9 8 NAYABAD MAIN ROAD ADHIR HALDAR LATE BABLU HALDAR 4 5 9 9 10 BIKASH GUHA COLONY 8 NAYABAD MUKUNDAPUR KOL-99 ADHIR HALDAR LT.KANGSHADHAR HALDAR 1 4 5 10 11 GANGA NAGAR GANGANAGAR ROAD ADHIR MAZUMDAR LATE JAMINI KANTA MAZUMDA 5 4 9 11 12 PURBA RAJAPUR D BLOCK D102 PURBA RAJAPUR D BLOCK ADHIR SARDAR 4 4 8 12 13 D-BLOCK D/104 PURBA RAJAPUR KOL-75 ADYABALA HALDER LT.TARANI HALDER 2 3 5 13 14 D BLOCK D/34 PURBARAJAPUR KOL-32 AJAY DAS LT.KARTIK DAS 1 1 2 14 15 N/12 SOHID SMRITY SADAN AJAY HAZRA LATE SUSIL HAZRA 2 4 6 15 16 4 CHHIT KALIKAPUR KOL-99 AJAY MONDAL DHANANJOY MONDAL 2 2 4 16 17 BIKASH GUHA COLONY 101 NAYABAD MAIN ROAD AJAY SARDAR LATE FANI SARDAR 2 3 5 17 18 B/5 SAHID SMIRTY COLONY AJIT DAS LATE SANTOSH DAS 2 4 6 18 19 SAHID SMRITI COLONI F-3 SAHID SMRITI COLONI KOL-94 AJIT HALDAR LT.BHIRU HALDAR 2 2 4 19 20 D BLOCK D/12 PURBARAJAPUR KOL-32 AJIT HALDER LT.JUDHISTIR HALDER 1 2 3 20 21 BUDHERHAT BUDHERHAT KOL-99 AJIT MONDAL GOPAL MONDAL 1 4 5 22 22 D-BLOCK D/136A PURBA RAJAPUR KOL-75 AJIT SARDAR LT.ANIL SARDAR 3 2 5 24 23 SAHID SMRITY COLONY F-3 SAHID SMRITY COLONY KOL-94 AJIT SARDAR LT. -

Kolkata Municipal Corporation, West Bengal

GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET KOLKATA MUNICIPAL CORPORATION, WEST BENGAL DISTRICT AT A GLANCE Sl. Items Statistics No. GENERAL INFORMATION i) Geographical Area (Sq. km.) 187.33 sq.km ii) Administrative Division (as on 2001) 1. No. Wards 141 iii) Population (as on 2001 Census) (with density of 45, 80,544 (24451.74 per sq.km.) population) iv) Normal Annual Rainfall (mm) 1647 GEOMORPHOLOGY Lower deltaic plains of the Ganga- Bhagirathi Major Physiographic Units river system Hugli river along its western boundary. 2. Several canals like Bagjola Khal in the north and Beleiaghata and Circular Khal in the Major Drainages central part and Adi-Ganga (a paleo channel), and Talli nala in the southern part cover a large area of the city. LAND USE (Sq.km.) (as on Urban area 3. 2004-05) (Kolkata Municipal Corporation). Younger alluvial soils mainly silty clay to 4. MAJOR SOIL TYPES clay. NUMBERS OF GROUND WATER MONITORING 5. WELLS OF CGWB (As on 21 (Tubewells-12, Piezometers-9) 31.03.07) No. of Piezometers/ Tube wells PREDOMINANT 8. GEOLOGICAL Recent alluvium. FORMATIONS 9. HYDROGEOLOGY Major Water bearing formation Quaternary alluvium 1 Pre-monsoon depth to water level 12.09 to 19.59 mbgl. during 2006 Post-monsoon depth to water 10.72 to 15.42 mbgl level during 2006 There is fall of 7 to 11m in ground water level in last 45 years from 1958 to 2003. Declining Long term water level trend in 10 trend of water level to the tune of 0.33m/yr at years (1997-2006) in m/yr the core of the trough and 0.11 m/yr at the periphery.