Learning for a Future: Refugee Education in Developing Countries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Islamist Politics in South Asia After the Arab Spring: Parties and Their Proxies Working With—And Against—The State

RETHINKING POLITICAL ISLAM SERIES August 2015 Islamist politics in South Asia after the Arab Spring: Parties and their proxies working with—and against—the state WORKING PAPER Matthew J. Nelson, SOAS, University of London SUMMARY: Mainstream Islamist parties in Pakistan such as the Jama’at-e Islami and the Jamiat-e-Ulema-e-Islam have demonstrated a tendency to combine the gradualism of Brotherhood-style electoral politics with dawa (missionary) activities and, at times, support for proxy militancy. As a result, Pakistani Islamists wield significant ideological influence in Pakistan, even as their electoral success remains limited. About this Series: The Rethinking Political Islam series is an innovative effort to understand how the developments following the Arab uprisings have shaped—and in some cases altered—the strategies, agendas, and self-conceptions of Islamist movements throughout the Muslim world. The project engages scholars of political Islam through in-depth research and dialogue to provide a systematic, cross-country comparison of the trajectory of political Islam in 12 key countries: Egypt, Tunisia, Morocco, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Syria, Jordan, Libya, Pakistan, as well as Malaysia and Indonesia. This is accomplished through three stages: A working paper for each country, produced by an author who has conducted on-the-ground research and engaged with the relevant Islamist actors. A reaction essay in which authors reflect on and respond to the other country cases. A final draft incorporating the insights gleaned from the months of dialogue and discussion. The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. -

Migration, Migrants and Child Poverty

Migration, migrants and child poverty Although international migration has always been a feature of national life, this aspect of population change has increased over the last twenty years, mostly as a result of asylum seekers arriving in the 1990s and, more recently, migration from the new member states of the European Union (EU). While many migrant families have a reasonable income and a few are very prosperous, migrant children are disproportionally represented among children living in poverty. Many of the causes of child poverty for migrants are similar to those facing the UK-born population, but there are some factors that are specific to migrant households, such as language barriers and the severing of support networks. Here, Jill Rutter examines the link between child poverty and migration in the UK. Who are migrants? In the last five years, there has also been a sig- The United Nations’ definition of migrants are nificant onward migration of migrant communi- people who are resident outside their country of ties from other EU countries. Significant numbers birth. Many migrants in the UK have British citi- of Somalis, Nigerians, Ghanaians, Sri Lankan zenship, have been resident in the UK for many Tamils and Latin Americans have moved to the years and are more usually described as mem- UK from other EU countries. While many have bers of minority ethnic communities. This article secured citizenship or refugee status elsewhere uses the term ‘foreign born’ to describe those in the EU, some are irregular migrants. Most will outside their country of birth, and uses the term have received their education outside the EU ‘new migrants’ in a qualitative sense to describe and may have different qualifications and prior those new to the UK. -

Migrant and Displaced Children in the Age of COVID-19

Vol. X, Number 2, April–June 2020 32 MIGRATION POLICY PRACTICE Migrant and displaced children in the age of COVID-19: How the pandemic is impacting them and what can we do to help Danzhen You, Naomi Lindt, Rose Allen, Claus Hansen, Jan Beise and Saskia Blume1 vailable data and statistics show that children middle-income countries where health systems have have been largely spared the direct health been overwhelmed and under capacity for protracted effects of COVID-19. But the indirect impacts periods of time. It is in these settings where the next A surge of COVID-19 is expected, following China, Europe – including enormous socioeconomic challenges – are potentially catastrophic for children. Weakened and the United States.3 In low- and middle-income health systems and disrupted health services, job countries, migrant and displaced children often and income losses, interrupted access to school, and live in deprived urban areas or slums, overcrowded travel and movement restrictions bear directly on camps, settlements, makeshift shelters or reception the well-being of children and young people. Those centres, where they lack adequate access to health whose lives are already marked by insecurity will be services, clean water and sanitation.4 Social distancing affected even more seriously. and washing hands with soap and water are not an option. A UNICEF study in Somalia, Ethiopia and the Migrant and displaced children are among the most Sudan showed that almost 4 in 10 children and young vulnerable populations on the globe. In 2019, around people on the move do not have access to facilities to 33 million children were living outside of their country properly wash themselves.5 In addition, many migrant of birth, including many who were forcibly displaced and displaced children face challenges in accessing across borders. -

Walk the Talk: Review of Donors' Humanitarian Policies on Education

WALK THE TALK Review of DonoRs’ HumanitaRian Policies on eDucation Design and layout: Amund Lie Nitter Cover photo: Hanne Bjugstad @Save the Children Photographs: Hanne Bjugstad, Jonathan Hyams, Georg Schaumberger, Hedinn Halldorsson, Luca Kleve-Ruud, Susan Warner, Prashanth Vishwanathan, Andrew Quilty, Vincent Tremeau, Becky Bakr Abdulla, Christian Jepsen, Ingrid Prestetun, Truls Brekke, Shahzad Ahmad, David Garcia Researched and written by: this study was commissioned by the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) and Save the Children and written by Elizabeth Wilson, Brian Majewski and Kerstin Tebbe (Avenir Analytics Ltd). Acknowledgements Particular thanks are due to Matthew Stephensen, Silje Sjøvaag Skeie, Nadia Bernasconi (Norwegian Refugee Council), Anette Remme (Save the Children), and Elin Martinez (formerly at Save the Children). The report has benefitted from additional input by the following: Phillippa Lei, Sylvi Bratten, Clare Mason, Bergdis Joelsdottir, Øygunn Sundsbø Brynildsen and Gunvor Knag Fylkesnes (Save the Children) and Petra Storstein, Sine Holen, Laurence Mazy, Mirjam Van Belle, Therese Marie Uppstrøm Pankratov, Elizabeth Hendry, and Ella Slater (NRC), Dean Brooks (formerly at NRC and now INEE) Ronit Cohen, (formerly INEE and now Save the Children), and Thomas Norman (independent consultant). The study was financed by: the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Norwegian Refugee Council and Save the Children Norway. Disclaimer: The analysis of donor policies and practices in this report represent the best judgment of the review team based on careful analysis of available data and do not necessarily represent the opinions of NRC or Save the Children. The Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) is an independent, international, humanitarian non- governmental organization which provides assistance, protection and contributes to durable solutions for refugees and internally displaced people worldwide. -

Position Paper on Migrant and Refugee Children

POSITION PAPER ON MIGRANT AND REFUGEE CHILDREN IMPRINT: © 2016 SOS Children’s Villages International – All rights reserved Editorial office: SOS Children’s Villages International Brigittenauer Lände 50, 1200 Vienna, Austria @SOS_Advocates www.sos-childrensvillages.org 2 INTRODUCTION There are more people on the move today than ever before. According to recently published data, the number of international migrants reached 244 million1 in 2015, while the number of refugees was 21.3 million2. People forcibly displaced by war and persecution reached a record high of over 65 million3. A UNHCR report4 noted that on average in 2015, 24 people were forced to flee their homes every minute – four times more than 10 years ago. Large-scale movements of people involve highly diverse groups, which move for different reasons. Poverty, inequality, conflict, violence and persecution, natural disasters and climate change are the main causes for people leaving or fleeing home, amongst others. Until these root causes are addressed, real and permanent change will not happen. People on the move are entitled to universal human rights under any circumstance, just like everyone else. International law provides special protections5 to migrants, asylum seekers and refugees to ensure they can exercise such rights in countries of origin, transit or destination alike. In practice however, their rights are often violated and they are subjected to discriminatory and arbitrary treatment. Children are no exception to this, although the Convention on the Rights of the Child (A/RES/44/25, esp. § 22.1) places on States the duty to ensure that all children enjoy their rights, regardless of their migration status or that of their parents. -

F Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

GOVERNMENT OF KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA COMMUNICATION & WORKS DEPARTMENT No. SOR/V-39/W&S/03/Vol-II Dated: 25/05/2021 To, The Chief Engineer (Centre), Communication & Works, Peshawar. SUBJECT: 2ND REVISED ADMINISTRATIVE APPROVAL FOR THE SCHEME "CONSTRUCTION OF TECHNICALLY & ECONOMICALLY FEASIBLE 198 KM ROADS IN PESHAWAR DIVISION" ADP NO.1702/200247 (2020-21). In exercise of the powers delegated vide Part-I Serial No.5 Second Schedule of the Delegation of Powers under the Financial Rules and Powers of Re-appropriation Rules, 2018, the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Provincial Government is pleased to accord the 2" Revised Administrative Approval for the implementation of the scheme under ADP NO.1702/200247 (2020-21)"Construction of Technically & Economically Feasible 198 KM Roads in Peshawar Division" ADP No.1702/200247 (2020-21)for the period of 26 months from (2020-21) to (2022-23) at a total cost of Rs. 4456.033 million (four thousand four hundred fifty six and thirty three thousand) as per detail given below: S.No. Name of work Total Cost (Rs in M) District Charsadda A Construction / Improvement and Widening of Road from Hassanzai to Munda Head (I) Works and Matta Mughal Khel via Katozai of Road from Shabqadar Chowk to Battagram, From Sokhta to Kotak and Dalazaak Bypass Dalazak Village District Charsadda 1 Construction/improvement and widening of Hassanzai road 3.00 km 69.92 2 Construction/Improvement and Widening of road from Shabqadar Chowk Battagram road (3.70km) 80.00 3 Advertisement charges 0.08 Total 150.00 (II) Construction / Improvement and -

Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan

Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan in Pakistan and Militancy Religion a report of the csis program on crisis, conflict, and cooperation Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan a literature review 1800 K Street, NW | Washington, DC 20006 Project Director Tel: (202) 887-0200 | Fax: (202) 775-3199 Robert D. Lamb E-mail: [email protected] | Web: www.csis.org Author Mufti Mariam Mufti June 2012 ISBN 978-0-89206-700-8 CSIS Ë|xHSKITCy067008zv*:+:!:+:! CHARTING our future a report of the csis program on crisis, conflict, and cooperation Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan a literature review Project Director Robert L. Lamb Author Mariam Mufti June 2012 CHARTING our future About CSIS—50th Anniversary Year For 50 years, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) has developed practical solutions to the world’s greatest challenges. As we celebrate this milestone, CSIS scholars continue to provide strategic insights and bipartisan policy solutions to help decisionmakers chart a course toward a better world. CSIS is a bipartisan, nonprofit organization headquartered in Washington, D.C. The Center’s 220 full-time staff and large network of affiliated scholars conduct research and analysis and de- velop policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. Since 1962, CSIS has been dedicated to finding ways to sustain American prominence and prosperity as a force for good in the world. After 50 years, CSIS has become one of the world’s pre- eminent international policy institutions focused on defense and security; regional stability; and transnational challenges ranging from energy and climate to global development and economic integration. -

The Border, Trafficking, and Risks to Unaccompanied Children— Understanding the Impact of U.S

The Border, Trafficking, and Risks to Unaccompanied Children— Understanding the Impact of U.S. Policy on Children’s Safety In the last decade, children and young families have become the face of migration at the U.S.-Mexico border. Tens of thousands of children have made the life-threatening journey from their countries alone; families have often come with small children—all to escape the violence from which they have no protection. No one wants these children to make this dangerous trip, or to see children torn from their mother or father’s arms. We want these children to be safe. More and more children and their families from Central America are making the trek to the United States, however, risking grave danger, as their desperation for a chance to be safe grows. Smugglers, traffickers, and other criminals often take advantage of this desperation among migrants, particularly unaccompanied children. What can we do to protect children and minimize their risks? Current laws provide a strong framework for protection, but there is a movement to thwart these laws, as some people argue, without evidence, that the laws designed to protect children create incentives for exploitation by migrants. This briefing paper takes a closer look at that claim, examining how current policies that seek to block the entry of children and asylum seekers contribute far more to the humanitarian crisis at the border than existing laws designed to protect children. If anything, those laws need to be strengthened, and our humanitarian commitment to children renewed—just the opposite of what is happening today. -

The Role of Ngos in Basic Education in Africa Civil Society Civil Societycivil Society Civil Societycivilsocietycivil Society Ci

The Role of NGOs in Basic Education in Africa c ivi l so ion cie g po ty c ov licy ivi ern ed l so no m uc ciet rs d ent atio y ci on go n p vil s or ver olic ociet s do nm y ed y civ no ent uca il society c rs d gov tion p ivil society civil society civil society civil soc ono ernm olicy ed iety civil rs d ent ucation policy education policy education po socie ono governm licy educ ty c rs do ent government government government g ation nors do overnmen pol nors donors donors donors donors donors d t gov onors don ernm ors do nors United States Agency for International Development, Bureau for Africa, Office of Sustainable Development Evolving Partnerships: The Role of NGOs in Basic Education in Africa Yolande Miller-Grandvaux Michel Welmond Joy Wolf July 2002 United States Agency for International Development Bureau for Africa, Office of Sustainable Development ii This review was prepared by the Support for Analysis and Research in Africa (SARA) project. SARA is operated by the Academy for Educational Development with subcontractors Tulane University, JHPIEGO, Morehouse School of Medicine, and Population Reference Bureau. SARA is funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development through the Bureau for Africa, Office of Sustainable Development (AFR/SD/HRD) under Contract AOT-C-00-99-00237-00. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Agency for International Development. -

Cluster Book 9 Printers Singles .Indd

PROTECTING EDUCATION IN COUNTRIES AFFECTED BY CONFLICT PHOTO:DAVID TURNLEY / CORBIS CONTENT FOR INCLUSION IN TEXTBOOKS OR READERS Curriculum resource Introducing Humanitarian Education in Primary and Junior Secondary Education Front cover A Red Cross worker helps an injured man to a makeshift hospital during the Rwandan civil war XX Foreword his booklet is one of a series of booklets prepared as part of the T Protecting Education in Conflict-Affected Countries Programme, undertaken by Save the Children on behalf of the Global Education Cluster, in partnership with Education Above All, a Qatar-based non- governmental organisation. The booklets were prepared by a consultant team from Search For Common Ground. They were written by Brendan O’Malley (editor) and Melinda Smith, with contributions from Carolyne Ashton, Saji Prelis, and Wendy Wheaton of the Education Cluster, and technical advice from Margaret Sinclair. Accompanying training workshop materials were written by Melinda Smith, with contributions from Carolyne Ashton and Brendan O’Malley. The curriculum resource was written by Carolyne Ashton and Margaret Sinclair. Booklet topics and themes Booklet 1 Overview Booklet 2 Legal Accountability and the Duty to Protect Booklet 3 Community-based Protection and Prevention Booklet 4 Education for Child Protection and Psychosocial Support Booklet 5 Education Policy and Planning for Protection, Recovery and Fair Access Booklet 6 Education for Building Peace Booklet 7 Monitoring and Reporting Booklet 8 Advocacy The booklets should be used alongside the with interested professionals working in Inter-Agency Network for Education in ministries of education or non- Emergencies (INEE) Minimum Standards for governmental organisations, and others Education: Preparedness, Response, Recovery. -

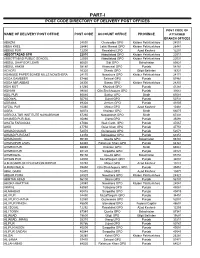

Part-I: Post Code Directory of Delivery Post Offices

PART-I POST CODE DIRECTORY OF DELIVERY POST OFFICES POST CODE OF NAME OF DELIVERY POST OFFICE POST CODE ACCOUNT OFFICE PROVINCE ATTACHED BRANCH OFFICES ABAZAI 24550 Charsadda GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 24551 ABBA KHEL 28440 Lakki Marwat GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28441 ABBAS PUR 12200 Rawalakot GPO Azad Kashmir 12201 ABBOTTABAD GPO 22010 Abbottabad GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 22011 ABBOTTABAD PUBLIC SCHOOL 22030 Abbottabad GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 22031 ABDUL GHAFOOR LEHRI 80820 Sibi GPO Balochistan 80821 ABDUL HAKIM 58180 Khanewal GPO Punjab 58181 ACHORI 16320 Skardu GPO Gilgit Baltistan 16321 ADAMJEE PAPER BOARD MILLS NOWSHERA 24170 Nowshera GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 24171 ADDA GAMBEER 57460 Sahiwal GPO Punjab 57461 ADDA MIR ABBAS 28300 Bannu GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28301 ADHI KOT 41260 Khushab GPO Punjab 41261 ADHIAN 39060 Qila Sheikhupura GPO Punjab 39061 ADIL PUR 65080 Sukkur GPO Sindh 65081 ADOWAL 50730 Gujrat GPO Punjab 50731 ADRANA 49304 Jhelum GPO Punjab 49305 AFZAL PUR 10360 Mirpur GPO Azad Kashmir 10361 AGRA 66074 Khairpur GPO Sindh 66075 AGRICULTUR INSTITUTE NAWABSHAH 67230 Nawabshah GPO Sindh 67231 AHAMED PUR SIAL 35090 Jhang GPO Punjab 35091 AHATA FAROOQIA 47066 Wah Cantt. GPO Punjab 47067 AHDI 47750 Gujar Khan GPO Punjab 47751 AHMAD NAGAR 52070 Gujranwala GPO Punjab 52071 AHMAD PUR EAST 63350 Bahawalpur GPO Punjab 63351 AHMADOON 96100 Quetta GPO Balochistan 96101 AHMADPUR LAMA 64380 Rahimyar Khan GPO Punjab 64381 AHMED PUR 66040 Khairpur GPO Sindh 66041 AHMED PUR 40120 Sargodha GPO Punjab 40121 AHMEDWAL 95150 Quetta GPO Balochistan 95151 -

Education Cannot Wait Facilitated Multi-Year Programme, Afghanistan 2018-2021

PROGRAMME DOCUMENT: Afghanistan EDUCATION CANNOT WAIT FACILITATED MULTI-YEAR PROGRAMME, AFGHANISTAN 2018-2021 Table of Contents Contents Programme Information Summary ............................................................................................................... 2 I. Analysis of Issues/Challenges .............................................................................................................. 5 II. Strategy and Theory of Change ......................................................................................................... 12 III. Results and Partnerships ................................................................................................................ 18 IV. Programme Management & Target Locations ............................................................................. 34 V. Results Framework .............................................................................................................................. 39 VI. Monitoring And Evaluation .............................................................................................................. 49 VII. Multi-Year Work Plan and Budget .................................................................................................. 51 VIII. Governance and Management Arrangements ............................................................................. 57 IX. Legal Context and Risk Management ........................................................................................... 63 X. ANNEXES .............................................................................................................................................