Palestinian Tribes, Clans, and Notable Families by Glenn E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FINAL REPORT: Evaluation of the Local Governance and Infrastructure Program

FINAL REPORT: Evaluation of the Local Governance and Infrastructure Program An evaluation of the effect of LGI's local government initiatives on institutional development and participatory governance Pablo Beramendi, Soomin Oh, Erik Wibbels July 24, 2018 AAID Research LabDATA at William & Mary Author Information Pablo Beramendi Professor of Political Science and DevLab@Duke Soomin Oh PhD Student and DevLab@Duke Erik Wibbels Professor of Political Science and DevLab@Duke The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and should not be attributed to AidData or funders of AidData’s work, nor do they necessarily reflect the views of any of the many institutions or individuals acknowledged here. Citation Beramendi, P., Soomin, O, & Wibbels, E. (2018). LGI Final Report. Williamsburg, VA: AidData at William & Mary. Acknowledgments This evaluation was funded by USAID/West Bank and Gaza through a buy-in to a cooperative agreement (AID-OAA-A-12-00096) between USAID's Global Development Lab and AidData at the College of William and Mary under the Higher Education Solutions Network (HESN) Program. The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Tayseer Edeas, Reem Jafari, and their colleagues at USAID/West Bank and Gaza, and of Manal Warrad, Safa Noreen, Samar Ala' El-Deen, and all of the excellent people at Jerusalem Media and Communication Centre. Contents 1 Executive Summary 1 1.1 Key Findings . .1 1.2 Policy Recommendations . .2 2 Introduction 3 3 Background 4 4 Research design 5 4.1 Matching . .6 4.1.1 Survey Design and Sampling . .8 4.1.2 World Bank/USAID LPGA Surveys . -

Ep Delegation for Relations with the Palestinian

Delegation for Relations with the Palestinian Legislative Council European Parliament/Palestinian Legislative Council 7th Interparliamentary Meeting East Jerusalem/Ramallah/Gaza/Hebron 29 April -3 May 2007 Report by Mr Kyriacos TRIANTAPHYLLIDES, Chairman of the Delegation CR\671268EN.doc PE 384.740 EN EN I. Introduction The visit of the EP delegation in Palestine was the first official contact between both sides since November 2005. Due to the situation in the region, several attempts to meet earlier had failed. Following the Hamas victory in the legislative elections in January 2006, the EP delegation insisted to meet with the newly elected government of national unity agreed in Mekka in February 2007. The representation of the Commission did not attend the meetings where Ministers from Hamas and the Prime Minister were present. (This is the reasoning for listing participants at the beginning of each meeting report). One week before travelling to Palestine, the Chair, in a meeting on 25 April 2007 with Deputies from the Knesset, announced that the Delegation wished to meet with members of the new government, including Hamas members. The reaction of the Chair of the Knesset delegation was quite positive. It is worth adding that the Israeli authorities were cooperative during the whole visit, especially at the airport in Tel Aviv and on the Gaza border. II. Meetings Monday 30 April 1. Briefing by ECTAO (European Technical Assistance Office for the West Bank and Gaza Strip) on the humanitarian and political situation in the Occupied Palestinian Territories. Location: ECTAO, Jerusalem, 09h00-10h15 Participants: John Kjaer (ECTAO Representative), Roy Dickinson (Head of Operations), Ana Gallo (Head of the Political Section), Mark Gallagher (Head of Section - Economic and Financial Cooperation), Regis Meritan (Head of Section - Infrastructure, Water, Environment, Agriculture and UNRWA), EP Delegation. -

West Bank and Gaza 2020 Human Rights Report

WEST BANK AND GAZA 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Palestinian Authority basic law provides for an elected president and legislative council. There have been no national elections in the West Bank and Gaza since 2006. President Mahmoud Abbas has remained in office despite the expiration of his four-year term in 2009. The Palestinian Legislative Council has not functioned since 2007, and in 2018 the Palestinian Authority dissolved the Constitutional Court. In September 2019 and again in September, President Abbas called for the Palestinian Authority to organize elections for the Palestinian Legislative Council within six months, but elections had not taken place as of the end of the year. The Palestinian Authority head of government is Prime Minister Mohammad Shtayyeh. President Abbas is also chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization and general commander of the Fatah movement. Six Palestinian Authority security forces agencies operate in parts of the West Bank. Several are under Palestinian Authority Ministry of Interior operational control and follow the prime minister’s guidance. The Palestinian Civil Police have primary responsibility for civil and community policing. The National Security Force conducts gendarmerie-style security operations in circumstances that exceed the capabilities of the civil police. The Military Intelligence Agency handles intelligence and criminal matters involving Palestinian Authority security forces personnel, including accusations of abuse and corruption. The General Intelligence Service is responsible for external intelligence gathering and operations. The Preventive Security Organization is responsible for internal intelligence gathering and investigations related to internal security cases, including political dissent. The Presidential Guard protects facilities and provides dignitary protection. -

Israeli Settlements in the Old City of Hebron

Islamic Heritage Architecture and Art II 199 ISRAELI SETTLEMENTS IN THE OLD CITY OF HEBRON WAEL SHAHEEN Department of Civil and Architectural Engineering, Palestine Polytechnic University, Palestine ABSTRACT Since the occupation of the city of Hebron in 1967, the Israeli authorities started a series of closure in the Old City both in public and private properties in order to impose the reality of the occupation on the city and its citizens and push them into abandoning it and to obliterate its features. Ever since that date, the occupation authorities have begun implementing a settlement project that aimed to surround the city with settlements. They established a set of settlement outposts in the neighborhoods that contain historical buildings, provided full protection to settlers, and took all measurements in placing pressure on the Palestinians in order to push them to leave by issued military orders that prevent the restoration and habitation of many buildings. They also completely closed all streets, neighborhoods and buildings of the Old City, forced curfews for long periods of time, and turned the Old City into a military barrack by establishing many barriers, monitoring and inspection points, which resulted the deportation of dozens of families, in addition to eliminating the economic recovery after shutting down many shops. Several parts of the Old City became completely deserted because of the economic consequences of land confiscation policy and many other policies like the multiple shutdowns and restrictions placed on movement. The Old City of Hebron still remains in 2017 similar to a ghost town, most of its streets are deserted and most of its shops are closed by welding iron, unlike the energetic and crowded streets on the other side of the checkpoint in area HI, where the Palestinian commercial activity moved to. -

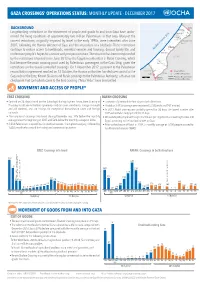

Gaza Crossings' Operations Status: Monthly

GAZA CROSSINGS’ OPERATIONS STATUS: MONTHLY UPDATE - DECEMBER 2017 BACKGROUND Erez Beit Lahiya ¹ ! Longstanding restrictions on the movement of people and goods to and from Gaza have under- ! Jabalya ! Beit Hanoun mined the living conditions of approximately two million Palestinians in that area. Many of the Gaza City ! n Sea ! Ash Shuja’iyeh current restrictions, originally imposed by Israel in the early 1990s, were intensified after June anea Nahal Oz Karni 2007, following the Hamas takeover of Gaza and the imposition of a blockade. These restrictions iterr GAZA Med 21 continue to reduce access to livelihoods, essential services and housing, disrupt family life, and 30! 0 undermine people’s hopes for a secure and prosperous future. The situation has been compounded Deir al B alah by the restrictions imposed since June 2013 by the Egyptian authorities at Rafah Crossing, which ISRAEL ! had become the main crossing point used by Palestinian passengers in the Gaza Strip, given the Khan Yunis Khuza’a ! restrictions on the Israeli-controlled crossings. On 1 November 2017, pursuant to the Palestinian 14389 Rafah EGYPT ! Crossing Point reconciliation agreement reached on 12 October, the Hamas authorities handed over control of the Sufa Rafah¹º» Closed Crossing Point Armistice Declaration Line Gaza side of the Erez, Kerem Shalom and Rafah crossings to the Palestinian Authority; a Hamas-run 5 Km ¹º» Kerem checkpoint that controlled access to the Erez crossing (“Arba’ Arba’”) was dismantled. Shalom International Boundary MOVEMENT AND ACCESS OF PEOPLE* EREZ CROSSING RAFAH CROSSING • Opened on 26 days (closed on five Saturdays) during daytime hours, from Sunday to • Exceptionally opened for four days in both directions. -

Eyeless in Gaza 21

Acram 1/24/04 1:49 AM Page 19 19 Eyeless Michael Ancram: Good to see you. Lots has happened since we last met.1 I guess you have in Gaza been busy, Gaza has been interesting, I’m keen The liberation of Alan to hear what has been going on. How do you Johnston and the think things will go? imprisonment of Gaza Usamah Hamdan: I will start from the Mecca Agreement. At Mecca there were three Daily in the common Prison important points. The first one was on the else enjoyn’d me, National Unity Government; the second point Where I a Prisoner chain’d, covered the reform of the security services and scarce freely draw called for a new security plan for the Palestinian The air imprison’d also, territories, and the third point was on the reform close and damp, of the PLO and the new political arrangements Unwholsom draught … inside the Palestinian political body. That means John Milton, the relations within the PLO itself, the relations Samson Agonistes between the PLO and the Palestinian Authority, the internal Palestinian relations.2 And we [in the Hamas movement] went back to Gaza and within one month there was the formation of the Usamah Hamden National Unity Government. We started talking about security. There was a security plan that Michael Ancram MP was put forward and that was endorsed by the Jonathan Lehrle government and that was then endorsed by Abu Mark Perry Mazen himself as President.3 When we started to apply that [the security plan] on the ground we faced an important problem – which was that the main General in the security service failed to apply and rejected 1. -

Hebron Governorate

Hebron Governorate: The Governorate of Hebron is located in the southern part of the West Bank. It is the largest Governorate in the West Bank in terms of size and population. Its area before the 1948 Nakba (disaster) was 2076 km2 while its current area is about 1060 km2. This means that Hebron has lost 51 % of its original size due to the events of Nakba. The population of the Governorate is now half million according to the estimates of the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (2005). The population density of the Governorate is 500 individuals per km2. Hebron Governorate ARAB STUDIES SOCIETY - Land Research Center (LRC) - Jerusalem , Halhul - Main Road 1 Tele / fax : 02 - 2217239, P.O.Box :35 Email: [email protected] URL : www.Ircj.org The number of Palestinian communities in the Governorate is 145, the largest of which is the city of Hebron. It has a built up area of 79.8 km2 (about 7.5 % of the total area of the Governorate). The Governorate of Hebron contains many religious, historical and archeological sites, the most important of which are: the Ibrahimi mosque, the Tel Arumaida area of ancient Hebron which started in the Bronze age – 3500 BC- the biblical site of Mamreh where Abraham pitched his tent and dug a well after his journey from Mesopotamia in 1850 BC, Al Ma’mudiay spring (probable baptismal site of Saint John the Baptist in the village of Taffuh), Saint Philip’s spring in Halhul where Saint Philip baptized the Ethiopian eunuch. Hebron Governorate Israeli Settlements in Hebron Governorate There are 22 Israeli settlements in Hebron Governorate with a built up area of 3.7 km2 (about 0.4% of the total area of Hebron Governorate) as illustrated by the attached map. -

November 2014 Al-Malih Shaqed Kh

Salem Zabubah Ram-Onn Rummanah The West Bank Ta'nak Ga-Taybah Um al-Fahm Jalameh / Mqeibleh G Silat 'Arabunah Settlements and the Separation Barrier al-Harithiya al-Jalameh 'Anin a-Sa'aidah Bet She'an 'Arrana G 66 Deir Ghazala Faqqu'a Kh. Suruj 6 kh. Abu 'Anqar G Um a-Rihan al-Yamun ! Dahiyat Sabah Hinnanit al-Kheir Kh. 'Abdallah Dhaher Shahak I.Z Kfar Dan Mashru' Beit Qad Barghasha al-Yunis G November 2014 al-Malih Shaqed Kh. a-Sheikh al-'Araqah Barta'ah Sa'eed Tura / Dhaher al-Jamilat Um Qabub Turah al-Malih Beit Qad a-Sharqiyah Rehan al-Gharbiyah al-Hashimiyah Turah Arab al-Hamdun Kh. al-Muntar a-Sharqiyah Jenin a-Sharqiyah Nazlat a-Tarem Jalbun Kh. al-Muntar Kh. Mas'ud a-Sheikh Jenin R.C. A'ba al-Gharbiyah Um Dar Zeid Kafr Qud 'Wadi a-Dabi Deir Abu Da'if al-Khuljan Birqin Lebanon Dhaher G G Zabdah לבנון al-'Abed Zabdah/ QeiqisU Ya'bad G Akkabah Barta'ah/ Arab a-Suweitat The Rihan Kufeirit רמת Golan n 60 הגולן Heights Hadera Qaffin Kh. Sab'ein Um a-Tut n Imreihah Ya'bad/ a-Shuhada a a G e Mevo Dotan (Ganzour) n Maoz Zvi ! Jalqamus a Baka al-Gharbiyah r Hermesh Bir al-Basha al-Mutilla r e Mevo Dotan al-Mughayir e t GNazlat 'Isa Tannin i a-Nazlah G d Baqah al-Hafira e The a-Sharqiya Baka al-Gharbiyah/ a-Sharqiyah M n a-Nazlah Araba Nazlat ‘Isa Nazlat Qabatiya הגדה Westהמערבית e al-Wusta Kh. -

Palestinian Territories MIDDLE EAST UNITARY COUNTRY and WEST ASIA

Palestinian territories MIDDLE EAST UNITARY COUNTRY AND WEST ASIA Basic socio-economic indicators Income group - LOWER MIDDLE INCOME Local currency - Israeli new shekel (ILS) Population and geography Economic data AREA: 6 020 km2 GDP: 19.4 billion (current PPP international dollars) i.e. 4 509 dollars per inhabitant (2014) POPULATION: million inhabitants (2014), an increase 4.295 REAL GDP GROWTH: -1.5% (2014 vs 2013) of 3% per year (2010-2014) UNEMPLOYMENT RATE: 26.9% (2014) 2 DENSITY: 713 inhabitants/km FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT, NET INFLOWS (FDI): 127 (BoP, current USD millions, 2014) URBAN POPULATION: 75.3% of national population GROSS FIXED CAPITAL FORMATION (GFCF): 18.6% of GDP (2014) CAPITAL CITY: Ramallah (2% of national population) HUMAN DEVELOPMENT INDEX: 0.677 (medium), rank 113 Sources: World Bank; UNDP-HDR, ILO Territorial organisation and subnational government RESPONSIBILITIES MUNICIPAL LEVEL INTERMEDIATE LEVEL REGIONAL OR STATE LEVEL TOTAL NUMBER OF SNGs 483 - - 483 Local governments - Municipalities (baladiyeh) Average municipal size: 8 892 inhabitantS Main features of territorial organisation. The Palestinian Authority was born from the Oslo Agreements. Palestine is divided into two main geographical units: the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. It is still an ongoing State construction. The official government of Cisjordania is governed by a President, while the Gaza area is governed by the Hamas. Up to now, most governmental functions are ensured by the State of Israel. In 1994, and upon the establishment of the Palestinian Ministry of Local Government (MoLG), 483 local government units were created, encompassing 103 municipalities and village councils and small clusters. Besides, 16 governorates are also established as deconcentrated level of government. -

Nablus City Profile

Nablus City Profile Prepared by The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem Funded by Spanish Cooperation 4102 Palestinian Localities Study Nablus Governorate Acknowledgments ARIJ hereby expresses its deep gratitude to the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID) for their funding of this project. ARIJ is grateful to the Palestinian officials in the ministries, municipalities, joint services councils, village committees and councils, and the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) for their assistance and cooperation with the project team members during the data collection process. ARIJ also thanks all the staff who worked throughout the past couple of years towards the accomplishment of this work. 1 Palestinian Localities Study Nablus Governorate Background This report is part of a series of booklets which contain compiled information about each city, town, and village in the Nablus Governorate. These booklets came as a result of a comprehensive study of all localities in the Nablus Governorate, and aim to depict the overall living conditions in the governorate and presenting developmental plans to assist in improving the livelihood of the population in the area. It was accomplished through the "Village Profiles and Needs Assessment" project funded by the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID). The "Village Profiles and Needs Assessment" was designed to study, investigate, analyze and document the socio-economic conditions and the programs and activities needed to mitigate the impact of the current insecure political, economic and social conditions in the Nablus Governorate. The project's objectives are to survey, analyze and document the available natural, human, socioeconomic and environmental resources, and the existing limitations and needs assessment for the development of the rural and marginalized areas in the Nablus Governorate. -

Palestine)0F

J OURNAL OF MUSLIM PHILANTHROPY & CIVIL SOCIETY 28 DISCONNECTED ACCOUNTABILITIES: INSTITUTIONALIZING ISLAMIC GIVING IN NABLUS (PALESTINE)0F Emanuel Schaeublin Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH Zurich) Zakat, the obligation to look after people in need by giving them a share of the wealth flowing through society, is recognized in the Islamic tradition as both a personal pious action and an institutional practice formalized by legal regimes. This dual character provides zakat with considerable malleability. Focusing on the trajectory of the “zakat committee” of Nablus since the 1970s, this article analyzes the different social and legal mechanisms that hold zakat committees in Palestine accountable. First, zakat committee members are under the constant observation of the local community and exposed to their ethical judgement. The local reputation of the zakat committee in Nablus depends on their integrity in running the committee and on their display of Muslim virtues in social interactions with others. Secondly, regional governments oversee zakat committees and hold them accountable. Finally, committee members have come under the increasing scrutiny of security surveillance and global policies of “combatting the financing of terrorism,” leading to forced closures in 2007. Due to the contested nature of political power in Nablus (the city has been under military occupation since 1967), these different mechanisms of accountability are sometimes remarkably disconnected. Notwithstanding, the malleability of zakat as a Copyright © 2020 Emanuel Schaeublin http://scholarworks.iu.edu/iupjournals/index.php/jmp DOI: 10.2979/muslphilcivisoc.4.2.02 Volume IV • Number II • 2020 J OURNAL OF MUSLIM PHILANTHROPY & CIVIL SOCIETY 29 Muslim practice adapting to changing circumstances provides this form of care for people in need with tenacity. -

Terminals, Agricultural Crossings and Gates

Terminals, Agricultural Crossings and Gates Umm Dar Terminals ’AkkabaDhaher al ’Abed Zabda Agricultural Gate (gap in the Wall) Controlled access through the Wall has been promised by the GOI to Ya’bad Wall (being finalised or complete) Masqufet al Hajj Mas’ud enable movement between Israel and the West Bank for Palestinian West Bank boundary/Green Line (estimate) Qaffin Imreiha populations who are either trapped in enclaves or isolated from their Road network agricultural lands. Palestinian Locality Hermesh Israeli Settlement Nazlat ’Isa An Nazla al Wusta According to Israel's State Attorney's office, five controlled crossings or NOTE: Agricultural Gate locations have been Baqa ash Sharqiya collected from field visits by OCHA staff and An Nazla ash Sharqiya terminals similar to the Erez terminal in northern Gaza will be built along information partners. The Wall trajectory is based on satellite imagery and field visits. An Nazla al Gharbiya the Wall. The Government of Israel recently decided that the Israeli Airport Authority will plan and operate the terminals. One of the main terminals between Israel and the West Bank appears to be being built Zeita Seida near Taibeh, 75 acres (300 dunums)35 in a part of Tulkarm City 36 Kafr Ra’i considered area A. ’Attil ’Illar The remaining terminals/control points are designated for areas near Jenin, Atarot north of Jerusalem, north of the Gush Etzion and near Deir al Ghusun Tarkumiyeh settlement bloc. Al Jarushiya Bal’a Agricultural Crossings and Gates Iktaba Al ’Attara The State Attorney's Office has stated that 26 agricultural gates will be TulkarmNur Shams Camp established along the length of the Wall to allow Palestinian farmers who Kafr Rumman have land west of the Wall, to cross.