The Gospel of Judas: Rewriting Early Christianity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GNOSIS and NAG HAMMADI Anne Mcguire

12 GNOSIS AND NAG HAMMADI Anne McGuire Introduction Introductory remarks on “gnosis” and “Gnosticism” “Gnosticism” is a modern European term that !rst appears in the seventeenth-century writings of Cambridge Platonist Henry More (1614–87). For More, “Gnosticism” designates one of the earliest Christian heresies, connected to controversies addressed in Revelation 2:18–29 and in his own day.1 The term “gnosis,” on the other hand, is one of several ancient Greek nouns for “knowledge,” speci!cally experiential or esoteric knowledge based on direct experience, which can be distinguished from mere perception, understanding, or skill. For Plato and other ancient thinkers, “gnosis” refers to that knowledge which enables perception of the underlying structures of reality, Being itself, or the divine.2 Such gnosis was valued highly in many early Christian communities,3 yet the claims of some early Christians to possess gnosis came under suspicion and critique in the post-Pauline letter of 1 Timothy, which urges its readers to “avoid the profane chatter and contradictions of falsely so-called gnosis.”4 With this began the polemical contrast between “false gnosis” and “true faith.” It is this polemical sense of “false gnosis” that Bishop Irenaeus of Lyons took up in the title of his major anti-heretical work: Refutation and Overthrow of Falsely So-Called Gnosis, or Against Heresies, written c. "# 180.5 Irenaeus used 1 Timothy’s phrase not only to designate his opponents’ gnosis as false, but, even more important, to construct a broad category of -

The Antedilusian Patriarche. by A

352 case must therefore have been due to another conclusion to Mark~ Gospel, whether Aristion or cause, and that was, in fact, the opposition of St. some other, had also no definite conception of the Paul. speaking with tongues, and, as we have seen, Nowhere in Paul’s later Epistles do we find any Irenpeus had just as little. Tertullian, on the mention of speaking with tongues; and the same other hand, knew of the phenomenon in its mon- is the case in the post-Pauline writings. We read, tanistic form, which we can now say resembled it is true, once more in Eph 51s, Be not drunken that of the early Christians. It was, perhaps, with wine, but be filled with the Spirit,’ but this even superior to the latter, in that the montanistic has reference more particularly to the prophets. oracles, although spoken in ecstasy, and in parts After a short time the nature of speaking with needing explanation, yet as far as the individual tongues was so little remembered, that though it words were concerned, appear to have been intel- was indeed not confounded with speaking in ligible. That could not always have been the case foreign languages, yet both could be associated as with the speaking with tongues. Nevertheless, the if they were similar in kind. Thus arose that Church has rejected this reaction, and rightly, conception of the miracle at Pentecost which now for this rejection is but the application of Paul’s lies before us in Ac 2, and which has really a asiom : ‘ God is not a God of confusion, but of deep and true meaning. -

Excommunicated Vol. 1, No. 1

Vol. 1, No. 1 (September 2014) excommunicated The newsletter of The International Society for Heresy Studies A biannual newsletter heresystudies.org Innaugural ISHS Conference: Brief Conference Heresy in the News Featured Heretic: Society News President’s Opening Remarks Impressions Geremy Carnes Simoni Deo Sancto Page 9 Gregory Erickson Jordan E. Miller Page 5 Edward Simon Page 1 Page 4 Gregory Erickson Page 8 Also: Robert Royalty Page 6 Check out the Vice-President’s Conference Page 4 John D. Holloway Teaching Corner Journal of Retrospective James Morrow Page 7 Bella Tendler Heresy Studies. Bernard Schweizer Page 4 Kathleen Kennedy Page 9 See page 10 for Page 2 Page 7 more information excommunicated is edited by Bernard Schweizer with assistance from Edward Simon and is designed by Jordan E. Miller The International Society for Heresy Studies Officers: Advisory Board Members: Contact: Gregory Erickson (president) Valentine Cunningham David Dickinson Gregory Erickson Bernard Schweizer (vice-president) Lorna Gibb Rebecca N. Goldstein 1 Washington Place, Room 417 John D. Holloway (secretary-treasurer) Jordan E. Miller James Morrow New York University Geremy Carnes (webmaster) Ethan Quillen Robert Royalty New York, NY 10003 James Wood INAUGURAL ISHS CONFERENCE: PRESIDENT’S OPENING REMARKS GREGORY ERICKSON Each of us was working with the concept of heresy in different ways. We agreed on wanting to form New York University some sort of organization. Much of our discussion I am very excited to welcome everyone to the first focused on why we each felt this sort of group was conference of the International Society of Heresy needed and what we meant by the word heresy. -

Pistis Sophia;

PISTIS SOPHIA; A GNOSTIC MISCELLANY: BEING FOR THE MOST PART EXTRACTS FROM THE BOOKS OF THE SAVIOUR, TO WHICH ARE ADDED EXCERPTS FROM A COGNATE LITERATURE; ENGLISHED By G. R. S. Mead. London: J. M. Watkins [1921] Biographical data: G. R. S. (George Robert Stow) Mead [1863-1933] NOTICE OF ATTRIBUTION. {rem Scanned at sacred-texts.com, June 2005. Proofed and formatted by John Bruno Hare. This text is in the public domain in the United States because it was published prior to 1923. It also entered the public domain in the UK and EU in 2003. These files may be used for any non-commercial purpose, provided this notice of attribution is left intact in all copies. p. v CONTENTS PAGE PREFACE xvii INTRODUCTION The Askew Codex xxi The Scripts xxii The Contents xxiii The Title xxiv The Date of the MS. xxv Translated from the Greek xxvi Originals composed in Egypt xxviii Date: The 2nd-century Theory xxix The 3rd-century Theory xxix The 'Ophitic' Background xxxi Three vague Pointers xxxii The libertinist Sects of Epiphanius xxxiii The Severians xxxiv The Bruce Codex xxxv The Berlin Codex xxxvi The so-called Barbēlō-Gnostics xxxvii The Sethians xxxviii The present Position of the Enquiry xxxviii The new and the old Perspective in Gnostic Studies xxxix The Ministry of the First Mystery xl The post-resurrectional Setting xli The higher Revelation within this Setting xlii The Æon-lore xlii The Sophia Episode xliii The ethical Interest xliii The Mysteries xliv The astral Lore xlv Transcorporation xlv The magical Element xlvi History and psychic Story xlvii The P.S. -

Antinomianism

ANTINOMIANISM (Greek ’αντι- [anti]—against; νομος [nomos]—custom, moral law)—a heretical Christian doctrine that rejects the law of the Old Testament (the decalogue); in a broader sense, a position that undermines the basis of ethical norms or denies their universality. The term antinomianism was used for the first time by M. Luther to describe John Agricola’s position on the role of the decalogue in the Church (the antinomian controversy in the years 1537–1540). As Agricola explained matters, love for Christ rather than a norm should a Christian’s only motive for acting, and since this is so the law is unnecessary; the state of grace is opposed to the order of law (the law of the Old Testament). Antinomianism in this sense was theoretical in character and had nothing in common with amoralism (practical antinomianism). However, a doctrine that rejected moral law (the decalogue, natural law, and the law of custom) on the basis of a pseudo-Christian doctrine appeared much earlier. Antinomianism appeared first in apostolic times among groups that had an anti-Judaistic attitude. It arose from a false explanation of St. Paul’s words (St. Peter writes of this—2 Pet 3, 15–16), which would seem to suggest a rejection of the Law of the Old Testament (“Without the Law, sin was dead” Rom 7, 8). The Apostle was merely showing that the law (or norm) makes man aware of evil (it does not evoke evil). St. Paul was showing rather that the Law was imperfect and explained that the performance of the deeds commanded by the Law does not assure man of salvation if this is not accompanied by the action of God’s grace (Rom 5, 20; 6, 14; 7, 5–25, and 1 Cor 15, 56, and Gal 3, 1). -

How the Epistle of Jude Illustrates Gnostic Ties with Jewish Apocalypticism Through Early Christianity

JUDE IN THE MIDDLE: HOW THE EPISTLE OF JUDE ILLUSTRATES GNOSTIC TIES WITH JEWISH APOCALYPTICISM THROUGH EARLY CHRISTIANITY _______________________________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board _______________________________________________________ in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY _______________________________________________________ by Boyd A. Hannold May, 2009 i ABSTRACT Jude in the Middle: How the Epistle of Jude Illustrates Gnostic Ties with Jewish Apocalypticism through Early Christianity Boyd A. Hannold Doctor of Philosophy Temple University, 2009 Vasiliki Limberis Ph.D. In the mid 1990’s, Aarhus University's Per Bilde detailed a new hypothesis of how Judaism, Christianity and Gnosticism were connected. Bilde suggested that Christianity acted as a catalyst, propelling Jewish Apocalypticism into Gnosticism. This dissertation applies the epistle of Jude to Per Bilde’s theory. Although Bilde is not the first to posit Judaism as a factor in the emergence of Gnosticism, his theory is unique in attempting to frame that connection in terms of a religious continuum. Jewish Apocalypticism, early Christianity, and Gnosticism represent three stages in a continual religio-historical development in which Gnosticism became the logical conclusion. I propose that Bilde is essentially correct and that the epistle of Jude is written evidence that the author of the epistle experiences the phenomena. The author of Jude (from this point on referred to as Jude) sits in the middle of Bilde’s progression and may be the most perceptive of New Testament writers in responding to the crisis. He looks behind to see the Jewish association with the Christ followers and seeks to maintain it. -

Cain's Ungodly Line and Seth's Godly Line Genesis 4:16-5:20

Return To Lowell F. Johnson Master Menu Return To Lowell F. Johnson Genesis Menu Cain's Ungodly Line and Seth's Godly Line Genesis 4:16-5:20 A period of some 1,500 years lies between the Fall and the Flood. Jesus, Himself, commented on this period “as the days of Noah were” (Matthew 24:37), so would be the days prior to His return. Two ancestral lines are traced in Genesis 4 and 5. The line of Cain is described first, the line of the ungodly; that of Seth, the line of the godly, is reviewed next. -The writer pauses with the seventh from Adam in both lines to give a view of how things have been developing. It has been noted that “without God, the more power we have the sooner we destroy ourselves; without God, the richer we are, the sooner we rot.” I. The Cainites: The Ungodly Line – 4:16-24 Notice: This is the Cainite civilization; not the Canaanite civilization. After he murdered Abel, Cain was sentenced by God to restlessly wander the earth. So when Cain went out from the Lord's presence to live in the land of Nod (Nod means “wandering) east of Eden, his head was “bloody but unbowed.” -He bore the gracious mark of protection, no one could kill him, but he would live forever with his guilty conscience, never feeling at home, never feeling entirely safe. He couldn't work the ground with success and he would not die for a long time. -Cain is now running from the Lord! What will he do? Where will he go? He will begin a secular society; a society that lived apart from God and in the Absence of His guidance. -

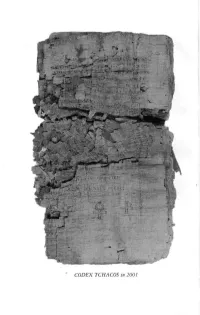

The Gospel of Judas from Codex Tchacos

THE GOSPEL OF JUDAS from Codex Tchacos EDITED BY RODOLPHE KASSER, MARVIN MEYER, and GREGOR WURST NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC Washington, D.C. Published by the National Geographic Society 1145 17th Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036-4688 Copyright © 2006 National Geographic Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, without permission in writing from the National Geographic Society. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available on request. DEFINING TIME PERIODS Many scholars and editors working today in the multicultural discipline of world history use ter minology that does not impose the standards of one culture on others. As recommended by the scholars who have contributed to the National Geographic Society's publication of the Gospel of Judas, this book uses the terms BCE (before the Common Era) and CE (Common Era). BCE refers to the same time period as B.C. (before Christ), and CE refers to the same time period as A.D. (anno Domini, a Latin phrase meaning "in the year of the Lord"). ISBN-10: 1-4262-0042-0 ISBN-13: 978-1-4262-0042-7 One of the world's largest nonprofit scientific and educational organizations, the National Geographic Society was founded in 1888 "for the increase and diffusion of geographic knowledge." Fulfilling this mission, the Society educates and inspires millions every day through its magazines, books, television programs, videos, maps and atlases, research grants, the National Geographic Bee, teacher workshops, and innovative classroom materials. The Society is supported through membership dues, charitable gifts, and income from the sale of its educational products. -

Gnostic Goddess, Female Power, and the Fallen Sophia ©2010 Max Dashu 1

The Gnostic Goddess, Female Power, and the Fallen Sophia ©2010 Max Dashu 1 Thou Mother of Compassion, come Come, thou revealer of the Mysteries concealed... Come, thou who givest joy to all who are at one with Thee Come and commune with us in this thanksgiving... —Gnostic hymn [Drinker, 150] Before the Roman triumph of Christianity, serious disagreements had already appeared among the believers. Gnostics were the first Christians to be expelled from the church as heretics. But not all Gnostics were Christian. Jewish Gnosticism predated Christianity, and pagan Gnostics who praised Prometheus and the Titans for opposing the tyranny of Zeus. [Geger, 168; Godwin, 85] Persian dualism, Hellenistic Neo-Platonism, and Egyptian mysticism were all influential in shaping Gnosticism. There was no one unified body of Gnostic belief. Though some Gnostic gospels were among the earliest Christian texts, all were banned from the orthodox canon that became the New Testament. Most people don't realize that the New Testament is a carefully screened selection from a much larger body of Christian scriptures. The others were not simply excluded from the official collection, but were systematically destroyed when Christianity became the state religion. [Epiphanius, in Legge, xliii] Egyptian Gnostics managed to protect an important cache of scriptures from the book-burners by burying them in large jars. Until the discovery of these Nag Hammadi scrolls in 1947, what little was known of the Gnostics came mostly from their sworn enemies, the orthodox clergy. [Pagels 1979: xxxv, xvii; Allegro, 108; Wentz, 363fn, lists a few surviving manuscripts known by 1900.] One of the few scriptures that did survive intact is the Pistis Sophia, while others are known fragmentarily from quotations in orthodox writings, especially those of Irenaeus and Hippolytus of Rome. -

A Companion to Second-Century Christian “Heretics” Supplements to Vigiliae Christianae Formerly Philosophia Patrum

A Companion to Second-Century Christian “Heretics” Supplements to Vigiliae Christianae Formerly Philosophia Patrum Texts and Studies of Early Christian Life and Language Editor J. den Boeft – J. van Oort – W.L. Petersen D.T. Runia – C. Scholten – J.C.M. van Winden VOLUME 76 A Companion to Second-Century Christian “Heretics” Edited by Antti Marjanen & Petri Luomanen BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2005 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A companion to second-century Christian “heretics” / edited by Antti Marjanen & Petri Luomanen. p. cm.—(Supplements to Vigiliae Christianae, ISSN 0920-623; v. 76) Including bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN 90-04-14464-1 (alk. paper) 1. Heresies, Christian. 2. Heretics, Christian—Biography. 3. Church history—Primitive and early church, ca. 30-600. I. Marjanen, Antti. II. Luomanen, Petri, 1961-. III. Series. BT1319.C65 2005 273'.1—dc22 2005047091 ISSN 0920-623X ISBN 90 04 14464 1 © Copyright 2005 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill Academic Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. printed in the netherlands CONTENTS Preface ......................................................................................... -

The “Unhistorical” Gospel of Judas

The “Unhistorical” Gospel of Judas Thomas A. Wayment ttributed to Jesus’ disciple Judas Iscariot, the Gospel of Judas (Codex A Tchacos) purports to preserve a private conversation between the mortal Savior and the Apostle who would betray him. A major ques- tion arising from this recently rediscovered Gnostic gospel is whether it contains any credible historical information about Judas, Jesus, or any of Jesus’ other disciples. There are several features that can be used to assess the historical value of this document, namely the physical or external his- tory of the document, internal literary clues or references, and compara- tive analysis based on the historical setting of the text. The Physical History of the Manuscript The Gospel of Judas was discovered nearly three decades ago, and its text, restored from thousands of fragments, was made public only recently. The Gospel of Judas, however, was not unknown to early Christians. In about ad 180, Irenaeus, a bishop of Lyons in France, denounced a Cainite Gnostic text that claimed to preserve the mystery of Christ’s betrayal. These Gnostic Christians, Irenaeus reported, believed in the exalted status of Cain and were likewise eager to promote Judas, who had also sought the destruction of the mortal body of Jesus. Irenaeus, therefore, has likely preserved the earliest known surviving reference to the Gospel of Judas. 1. Irenaeus, Against Heresies, 1.31.1, in Ante-Nicene Fathers, ed. Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson, 10 vols. (Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson, 1995), 1:358. 2. “Others again declare that Cain derived his being from the Power above, and acknowledge that Esau, Korah, the Sodomites, and all such persons, are BYU Studies 5, no. -

From Jewish Magic to Gnosticism

Studien und Texte zu Antike und Christentum Studies and Texts in Antiquity and Christianity Herausgeber/Editor: CHRISTOPH MARKSCHIES (Berlin) Beirat/Advisory Board HUBERT CANCIK (Berlin) • GIOVANNI CASADIO (Salerno) SUSANNA ELM (Berkeley) • JOHANNES HAHN (Münster) JÖRG RÜPKE (Erfurt) 24 Attilio Mastrocinque From Jewish Magic to Gnosticism Mohr Siebeck ATTILIO MASTROCINQUE, born 1952; Graduate of the University of Venice, Faculty of Humanities; 1975-1976 post-graduate studies at the Istituto Italiano per gli Studi Storici, Naples; 1978-1981 Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche fellowship; 1981-1987 Researcher, Ancient History, at the University of Venice, Faculty of Humanities; from 1992- Alexander von Humboldt-Stiftung research fellow; 1987-1995 Professor of Greek History at the University of Trento; 1995-2002 Professor of Greek History at the Univer- sity of Verona; since 2000 Professor of Roman History at the University of Verona. ISBN 3-16-148555-6 ISSN 1436-3003 (Studien und Texte zu Antike und Christentum) Die Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data is available on the Internet at http://dnb.ddb.de. €> 2005 by Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen, Germany. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher's written permission. This applies particularly to reproduc- tions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was typeset by Martin Fischer in Tübingen using Times typeface, printed by Guide- Druck in Tübingen on non-aging paper and bound by Buchbinderei Spinner in Ottersweier. Printed in Germany. Preface This book has been conceived as a continuation of my study on Mithraism and magic, because I maintain that Pliny the Elder was correct in stating that the two main streams of magic arts in the Imperial Age were the Persian and the Jewish ones.