Zooming in on Google Street View and the Global Right to Privacy Lauren H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Creating Google Street Views with the Samsung Gear 360 Camera By

Creating Google Street Views with the Samsung Gear 360 Camera1 by Andy Lyons Last modified: November 2016 Google Street View Camera Loan Kit In October 2016, Google loaned a 360-camera kit to IGIS (a statewide technical support program in ANR), for the purposes of exploring how Google’s Street View technology can be useful for research and management at the Hopland Research and Extension Center (and ANR field stations more generally). Street View app and the Samsung Gear 360 2 The Street View app (for both Android and iOS) is what you use to create and upload Street Views. The Samsung Gear 360 is one of about four 360 cameras that the Google Street View app is setup to work with (meaning the app can control the camera pretty seamlessly). Most people use the Street View app only to view off-road street views. You can also view off-road street views in plain old Google Maps, but the Street View app makes it a little easier to find user generated content. If you have a VR device such as the Google Cardboard, you can view Street Views in 3 cardboard mode . In terms of content creation, the Street View app has three main functions: i) control the camera, ii) process images (which includes stitching them together, blurring faces and license plates, adding locations as needed, and linking nearby photos), and iii) upload the images to Google Street View (after which they’ll be available in Google Maps immediately). The Samsung Gear can also record 360 video. For that you need the Samsung Gear 360 Manager (or another app). -

Issues Paper on Cyber-Crime Affecting Personal Safety, Privacy and Reputation Including Cyber-Bullying (LRC IP 6-2014)

Issues Paper on Cyber-crime affecting personal safety, privacy and reputation including cyber-bullying (LRC IP 6-2014) BACKGROUND TO THIS ISSUES PAPER AND THE QUESTIONS RAISED This Issues Paper forms part of the Commission’s Fourth Programme of Law Reform,1 which includes a project to review the law on cyber-crime affecting personal safety, privacy and reputation including cyber-bullying. The criminal law is important in this area, particularly as a deterrent, but civil remedies, including “take-down” orders, are also significant because victims of cyber-harassment need fast remedies once material has been posted online.2 The Commission seeks the views of interested parties on the following 5 issues. 1. Whether the harassment offence in section 10 of the Non-Fatal Offences Against the Person Act 1997 should be amended to incorporate a specific reference to cyber-harassment, including indirect cyber-harassment (the questions for which are on page 13); 2. Whether there should be an offence that involves a single serious interference, through cyber technology, with another person’s privacy (the questions for which are on page 23); 3. Whether current law on hate crime adequately addresses activity that uses cyber technology and social media (the questions for which are on page 26); 4. Whether current penalties for offences which can apply to cyber-harassment and related behaviour are adequate (the questions for which are on page 28); 5. The adequacy of civil law remedies to protect against cyber-harassment and to safeguard the right to privacy (the questions for which are on page 35); Cyber-harassment and other harmful cyber communications The emergence of cyber technology has transformed how we communicate with others. -

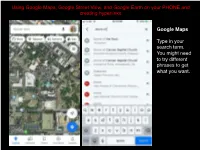

Using Google MAPS Street View on Your PHONE and Creating Hyperlinks

Using Google Maps, Google Street View, and Google Earth on your PHONE and creating hyperlinks Google Maps Type in your search term. You might need to try different phrases to get what you want. Pull the bottom screen up to see the Overview and click on Photos Switch to “Street View & 360” and search through the images listed, opening them by clicking on them. Once in the 360 degree view you can move your view around by swiping on the screen (you can also do this to the smaller preview images in the list). Once you have found the view that “explains the ways in which it augments understanding of the monument/place/site/object itself, beyond your readings or what has been discussed in class” save the view as the choice for your Spatial Exploration Project entry. To do this click on the “share” icon (a square with an arrow projecting from it) that I’ve outlined in red at the top of the page. At this point you can text or email yourself the link or copy it to paste into a document. To create a hyperlink in your document, highlight the text you want to be connected to your view, paste the copied url you made from the previous share screen, hit ”go” or “enter,” and that text will now have the link embedded in it. Google Street View While less well known than Google Maps, Street View allows you to walk the streets of the location you choose. Once again, you type in your search term. -

Photographs in Public Places and Privacy

[2009] 2 Journal of Media Law 159–171 Photographs in Public Places and Privacy Kirsty Hughes In the last few years, the European Court of Human Rights (‘the Court’) has considered a number of cases relating to photographs taken in public places, and it is now clear that the jurisprudence has evolved significantly since the early cases in which no protection was afforded to the privacy interests of those photographed. The most recent cases (Reklos and Davourlis v Greece and Egeland and Hanseid v Norway) have extended the protection afforded by Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) so that the right is engaged at the stage at which photographs are taken.1 The author argues that whilst this development was necessary, there are a number of problems with the Court’s approach and that further guidance from the Court is essential. THEORIES OF PRIVACY-RELATED INTERESTS To fully understand the significance of the Article 8 ECHR photography cases, one has to have some idea of how these cases relate to the protection of privacy. There are many different theories of privacy and privacy-related interests and it is beyond the scope and purpose of this commentary to examine the details of those theories here.2 However, it * Clare College, University of Cambridge. 1 (App No 1234/05) [2009] EMLR 16 and (App No 34438/04) [2009] ECHR 622, available on HUDOC. 2 The literature is extensive; a good starting point would be Ruth Gavison, ‘Privacy and the Limits of the Law’ (1980) 89(3) Yale Law Journal 421; Hyman Gross, ‘Privacy and Autonomy’ -

Google Street View As a Medium for Social Gaming Steven Dao

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Senior Theses Honors College Spring 5-5-2017 Google Street View as a Medium for Social Gaming Steven Dao Tien Ho Austin Pahl Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/senior_theses Part of the Computer Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Dao, Steven; Ho, Tien; and Pahl, Austin, "Google Street View as a Medium for Social Gaming" (2017). Senior Theses. 145. https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/senior_theses/145 This Thesis is brought to you by the Honors College at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GOOGLE STREET VIEW AS A MEDIUM FOR SOCIAL GAMING By Steven Dao Tien Ho Austin Pahl Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation with Honors from the South Carolina Honors College May, 2017 Approved: Dr. Jose M. Vidal Director of Thesis Steve Lynn, Dean For South Carolina Honors College Table of Contents Thesis Summary 4 Introduction 4 Planning 5 Waterfall Development Process 5 Technologies 5 Collaboration/Communication Tools 5 Frontend Frameworks 6 Angular 2 6 AngularFire 2 7 Bootstrap 7 HowlerJS 8 Google Maps API 8 Backend Frameworks 8 Firebase 8 Django 8 MEAN Stack 9 Frontend and Backend Overview 9 Design 10 Mockups 10 Architecture 12 Requirements 13 Implementation 15 Architecture 15 Services 15 Components 15 UML Diagram 16 Challenges/Issues 17 Validation 18 Testing 18 Debugging 19 Results 19 Finished App 19 Presentations 21 References 22 Appendix: Tools and Technologies Used 23 2 Thesis Summary In this thesis project, we planned and built a multiplayer web game called safehouse from Fall 2016 to Spring 2017. -

A Right That Should've Been: Protection of Personal Images On

275 A RIGHT THAT SHOULD’VE BEEN: PROTECTION OF PERSONAL IMAGES ON THE INTERNET EUGENIA GEORGIADES “The right to the protection of one’s image is … one of the essential components of personal development.” Grand Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights ABSTRACT This paper provides an overview of the current legal protection of personal images that are uploaded and shared on social networks within an Australian context. The paper outlines the problems that arise with the uploading and sharing of personal images and considers the reasons why personal images ought to be protected. In considering the various areas of law that may offer protection for personal images such as copyright, contract, privacy and the tort of breach of confidence. The paper highlights that this protection is limited and leaves the people whose image is captured bereft of protection. The paper considers scholarship on the protection of image rights in the United States and suggests that Australian law ought to incorporate an image right. The paper also suggests that the law ought to protect image rights and allow users the right to control the use of their own image. In addition, the paper highlights that a right to be forgotten may provide users with a mechanism to control the use of their image when that image has been misused. Dr. Eugenia Georgiades, Assistant Professor Faculty of Law, Bond University, the author would like to thank Professor Brad Sherman, Professor Leanne Wiseman and Dr. Allan Ardill for their feedback. Volume 61 – Number 2 276 IDEA – The Law Review of the Franklin Pierce Center for Intellectual Property Abstract .......................................................................... -

Tech Giants, Freedom of Expression and Privacy

TECH GIANTS, FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION AND PRIVACY TECH GIANTS, FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION AND PRIVACY Rikke Frank Jørgensen & Marya Akhtar e-ISBN: 978-87-93893-77-1 © 2020 The Danish Institute for Human Rights Wilders Plads 8K DK-1403 Copenhagen K Phone +45 3269 8888 www.humanrights.dk Provided such reproduction is for non-commercial use, this publication, or parts of it, may be reproduced if author and source are quoted. At DIHR we aim to make our publications as accessible as possible. We use large font size, short (hyphen-free) lines, left-aligned text and strong contrast for maximum legibility. For further information about accessibility please click www.humanrights.dk/accessibility 2 CONTENT 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................... 5 2 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................. 7 3 WHAT IS A TECH GIANT ................................................................................. 9 4 HUMAN RIGHTS PROTECTION ...................................................................... 11 4.1 THE UN ..................................................................................................... 11 4.1.1 binding rules.......................................................................................... 11 4.1.2 guidelines and recommendations .......................................................... 13 4.2 THE COUNCIL OF EUROPE AND THE EUROPEAN COURT OF HUMAN RIGHT ........................................................................................................... -

In the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Texas Marshall Division

Case 2:18-cv-00549 Document 1 Filed 12/30/18 Page 1 of 40 PageID #: 1 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS MARSHALL DIVISION UNILOC 2017 LLC § Plaintiff, § CIVIL ACTION NO. 2:18-cv-00549 § v. § § PATENT CASE GOOGLE LLC, § § Defendant. § JURY TRIAL DEMANDED § ORIGINAL COMPLAINT FOR PATENT INFRINGEMENT Plaintiff Uniloc 2017 LLC (“Uniloc”), as and for their complaint against defendant Google LLC (“Google”) allege as follows: THE PARTIES 1. Uniloc is a Delaware limited liability company having places of business at 620 Newport Center Drive, Newport Beach, California 92660 and 102 N. College Avenue, Suite 303, Tyler, Texas 75702. 2. Uniloc holds all substantial rights, title and interest in and to the asserted patent. 3. On information and belief, Google, a Delaware corporation with its principal office at 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043. Google offers its products and/or services, including those accused herein of infringement, to customers and potential customers located in Texas and in the judicial Eastern District of Texas. JURISDICTION 4. Uniloc brings this action for patent infringement under the patent laws of the United States, 35 U.S.C. § 271 et seq. This Court has subject matter jurisdiction pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §§ 1331 and 1338(a). Page 1 of 40 Case 2:18-cv-00549 Document 1 Filed 12/30/18 Page 2 of 40 PageID #: 2 5. This Court has personal jurisdiction over Google in this action because Google has committed acts within the Eastern District of Texas giving rise to this action and has established minimum contacts with this forum such that the exercise of jurisdiction over Google would not offend traditional notions of fair play and substantial justice. -

The Failure to Define the Public Interest in Axel Springer AG V

Boston College International and Comparative Law Review Volume 36 Article 5 Issue 3 Electronic Supplement 2-18-2014 Meaningful Journalism or "Infotainment"? The Failure to Define the Public nI terest in Axel Springer AG v. Germany Kathryn Manza Boston College Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/iclr Part of the Communications Law Commons, Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, First Amendment Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Kathryn Manza, Meaningful Journalism or "Infotainment"? The Failure to Define the Public Interest in Axel Springer AG v. Germany, 36 B.C. Int'l & Comp. L. Rev. E. Supp. 61 (2014), http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/iclr/vol36/iss3/5 This Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College International and Comparative Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MEANINGFUL JOURNALISM OR “INFOTAINMENT”? THE FAILURE TO DEFINE THE PUBLIC INTEREST IN AXEL SPRINGER AG v. GERMANY Kathryn Manza* Abstract: Although American courts provide wide discretion for freedom of the press, the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms ensures that the right to privacy enjoys equal footing with freedom of expression in Europe. When navigating the grey areas between these two frequently opposing rights, the European Court of Human Rights allows private information about a public figure to be published only to the extent the information contributes to the public in- terest. -

Places API-Powered Navigation

Places API-Powered Navigation A Case Study with Mercedes-Benz Mike Cheng & Kal Mos Mercedes-Benz Research & Development NA Google Features in Mercedes-Benz Cars Already Connected to Google Services via The MB Cloud • Setup: - Embedded into the HeadUnit - Browser-based - Connects via a BT tethered phone in EU & via embedded phone in USA • Features: - Google Local Search - Street View & Panoramio - Google Map for New S-Class 2 What Drivers Want* Private Contents Hint: More Business Contents Safe Access While Driving • Easy, feature-rich smartphone integration. • Use smartphone for navigation instead of the system installed in their vehicle (47% did that). • Fix destination Input & selection (6 of the top 10 most frequent problems). • One-shot destination entry is the dream. * J.D. Power U.S. Automotive Emerging Technologies Study 2013 - J.D. Power U.S. Navigation Usage & Satisfaction Study 3 What We Have: Digital DriveStyle App • Smartphone-based • Quick update cycle + continuous innovation. • Harness HW & SW power of the smartphone • Uses car’s Display, Microphone, Speakers, Input Controls,.. 4 What We Added A Hybrid Navigation: Onboard Navi Powered by Google Places API • A single “Google Maps” style text entry and search box with auto- complete. • Review G+ Local Photos, Street View, ratings, call the destination phone or navigate. • Overlay realtime information on Google maps such as weather, traffic, ..etc. 5 Challenges Automotive Related Challenges • Reliability requirements • Release cycles • Automotive-grade hardware • Driver distractions -

'The Right to Be Forgotten: More Than a Pandora's Box?'

Rolf H. Weber The Right to Be Forgotten More Than a Pandora’s Box? by Rolf H. Weber,* Dr.; Chair Professor for International Business Law at the University of Zurich and Visiting Professor at the University of Hong Kong Abstract: Recently, political voices have ple of free speech. Therefore, its scope needs to be stressed the need to introduce a right to be forgot- evaluated in the light of appropriate data protection ten as new human right. Individuals should have the rules. Insofar, a more user-centered approach is to right to make potentially damaging information dis- be realized. “Delete” can not be a value as such, but appear after a certain time has elapsed. Such new must be balanced within a new legal framework. right, however, can come in conflict with the princi- Keywords: Data protection; delete; free speech; privacy; privacy enhancing technologies; user-centered ap- proach © 2011 Rolf. H. Weber Everybody may disseminate this article by electronic means and make it available for download under the terms and conditions of the Digital Peer Publishing Licence (DPPL). A copy of the license text may be obtained at http://nbn-resolving. de/urn:nbn:de:0009-dppl-v3-en8. Recommended citation: Rolf H. Weber, The Right to Be Forgotten: More Than a Pandora’s Box?, 2 (2011) JIPITEC 120, para. 1. A. Introduction specific “case” is described in Mayer-Schönberg- er’s book Delete: The Virtue of Forgetting in the Digital 4 1 In 2010 a first legislative project was developed in Age. Stacy Snyder, a 25-year-old former education France that envisaged -

Pinning Down Abuse on Google Maps

Pinning Down Abuse on Google Maps Danny Yuxing Huangx, Doug Grundmanz, Kurt Thomasz, Abhishek Kumarz, Elie Burszteinz, Kirill Levchenkox, and Alex C. Snoerenx x{dhuang, klevchen, snoeren}@cs.ucsd.edu, z{dgrundman, kurtthomas, abhishekkr, elieb}@google.com xUniversity of California, San Diego zGoogle Inc ABSTRACT also ripe for abuse. Early forms of attacks included defacement, In this paper, we investigate a new form of blackhat search engine such as graffiti posted to Google Maps in Pakistan [13]. How- optimization that targets local listing services like Google Maps. ever, increasing economic incentives are driving an ecosystem of Miscreants register abusive business listings in an attempt to siphon deceptive business practices that exploit localized search, such as search traffic away from legitimate businesses and funnel it to de- illegal locksmiths that extort victims into paying for inferior ser- ceptive service industries—such as unaccredited locksmiths—or vices [9]. In response, local listing services like Google Maps em- to traffic-referral scams, often for the restaurant and hotel indus- ploy increasingly sophisticated verification mechanisms to try and try. In order to understand the prevalence and scope of this threat, prevent fraudulent listings from appearing on their services. we obtain access to over a hundred-thousand business listings on In this work, we explore a form of blackhat search engine opti- Google Maps that were suspended for abuse. We categorize the mization where miscreants overcome a service’s verification steps types of abuse affecting Google Maps; analyze how miscreants cir- to register fraudulent localized listings. These listings attempt to cumvented the protections against fraudulent business registration siphon organic search traffic away from legitimate businesses and such as postcard mail verification; identify the volume of search instead funnel it to profit-generating scams.