Social Exclusion and the Provision of Public Transport

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

674 Mac Private Uesidents

674 MAC PRIVATE UESIDENTS. (NORTH AND EAST RIDJNGS l'lcLansborough Joseph Wm. Tile;y, Malcolm Percy S. 3 Holbeck road, Ma.rshall Rev. James McCall M.A. The Poplars, Ooatham, Redcar Scarborough u~ctury, t..roft, Varlingtoa N:cLaren Frederic Donuld, 28 Nor-. Maley Mrs. 24 Scarborough rd. Filey Marshal} A. 5 l::louthcliff rd. Withern- wood; Beverley Malim Rev. "\V. G., B.A. Kilverstone l!ea, .l:l.uH McLa.uchlan J o .. eph, 9 !me;; on terrace, villa, Scalby road, Scarborough Mar.s.bal! AlfreJ, 7 Hemy ~otreet, Linthorpe road, Middlesbrough Malley Horace William R. 2 LindPn Loat.bam, Redcar McLaughlin George, 219 Prospect rd. grove, Linthorpe, Middlesbrough Marshall C.J. 12 Grove Hill rd.Bevrly Scar borough Mallin J oseph James, Ewin house, ..\l.arshall Erskine H. 7 1rafalgar s~. McLean Samuel Moore, 16 Trinity Grove hill, Middlesbrou!rh l::lcarborough road, Bridlington . :Mallin Mrs. J oseph, 85 Douglas ter. Marshall l'. Herbert, West par.-, .M:aclennan Daniel, 2 Brookside, Borough road west, Middle:>brongh \)'est road, Loftus Croydon road, Middlesbrough Mu1linder Rev. Dacre, Scorton,Drlngtn Mar.shall Frederick William, Sherbutt .MacLeod John Farquhar M.B. 71 Mallinson Miss, West lane,Hedon,Hull ho. Napham rd. Pock.lington, York ~ormanby road, South Bank Yallory Geo. The Fields, Nunthorpe M.arshall George, Hmderwell Macleod Mrs.. 8 Newbegin, Beverley Mallory Mrs. 1 Carlton st.Bridlington Marshall J.Terrace ho.Burstwick,Hull McLoughry James Wilson, Avondale, Mallory Mrs. Uppleby, Easingwold Marsh all John, 1'he Poplars, Croh, Thornfield rd. Linthorpe,Middlsbro' Mallory Richard Watson, South side, Da.rlingt-on McMahon Rev. -

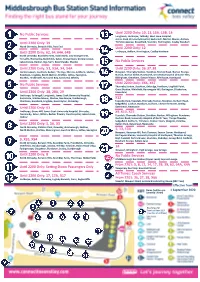

Middlesbrough Bus Station

No Public Services Until 2200 Only: 10, 13, 13A, 13B, 14 Longlands, Linthorpe, Tollesby, West Lane Hospital, James Cook University Hospital, Easterside, Marton Manor, Acklam, Until 2200 Only: 39 Trimdon Avenue, Brookfield, Stainton, Hemlington, Coulby Newham North Ormesby, Berwick Hills, Park End Until 2200 Only: 12 Until 2200 Only: 62, 64, 64A, 64B Linthorpe, Acklam, Hemlington, Coulby Newham North Ormesby, Brambles Farm, South Bank, Low Grange Farm, Teesville, Normanby, Bankfields, Eston, Grangetown, Dormanstown, Lakes Estate, Redcar, Ings Farm, New Marske, Marske No Public Services Until 2200 Only: X3, X3A, X4, X4A Until 2200 Only: 36, 37, 38 Dormanstown, Coatham, Redcar, The Ings, Marske, Saltburn, Skelton, Newport, Thornaby Station, Stockton, Norton Road, Norton Grange, Boosbeck, Lingdale, North Skelton, Brotton, Loftus, Easington, Norton, Norton Glebe, Roseworth, University Hospital of North Tees, Staithes, Hinderwell, Runswick Bay, Sandsend, Whitby Billingham, Greatham, Owton Manor, Rift House, Hartlepool No Public Services Until 2200 Only: X66, X67 Thornaby Station, Stockton, Oxbridge, Hartburn, Lingfield Point, Great Burdon, Whinfield, Harrowgate Hill, Darlington, (Cockerton, Until 2200 Only: 28, 28A, 29 Faverdale) Linthorpe, Saltersgill, Longlands, James Cook University Hospital, Easterside, Marton Manor, Marton, Nunthorpe, Guisborough, X12 Charltons, Boosbeck, Lingdale, Great Ayton, Stokesley Teesside Park, Teesdale, Thornaby Station, Stockton, Durham Road, Sedgefield, Coxhoe, Bowburn, Durham, Chester-le-Street, Birtley, Until -

100% Prime Retail Unit Let to Arcadia Group for a Further 22 Years 7 Months

100% PRIME RETAIL UNIT LET TO ARCADIA GROUP FOR A FURTHER 22 YEARS 7 MONTHS 62A, 64 and 66 Linthorpe Road & 1 Corporation Street, Middlesbrough TS1 1RA EXECUTIVE SUMMARY n 100% prime location amongst leading national retailers n Immediately opposite the recently opened Flannels, Sports Direct and USC units n Let for a further 22 years and 7 months to the Arcadia Group n Passing rent of £174,000 per annum n Freehold n Asking price - £3.11M (Three million, one hundred and ten thousand pounds) excluding VAT reflecting a net initial yield of 5.25% after purchasers’ costs at 6.46% 100% PRIME RETAIL UNIT LET TO ARCADIA GROUP FOR A FURTHER 22 YEARS 7 MONTHS LOCATION Middlesbrough is the economic and The economy within Middlesbrough is administrative centre for Teesside. The town based predominantly on manufacturing, is located approximately 40 miles south of chemical production, and shipping with Newcastle, 12 miles east of Darlington and Tees Port providing major employment 60 miles north east of Leeds. opportunities. Tees Port is currently the 3rd Middlesbrough has a population of largest port in the UK and one of the 10th 138,900 (Middlesbrough Council 2016) largest in Western Europe handling over with a wider catchment population of 56m tons of domestic international cargo. 662,600 within a radius of 12 miles. Middlesbrough also has a thriving University with a student body in excess The town is easily accessible from the A66 of 24,000 contributing over £124m per leading to the A19 and A1(M). By rail the annum to the Middlesbrough economy. -

14, Arncliffe Road, West Lane, Middlesbrough, TS5 4AR Asking Price £85,000

14, Arncliffe Road, West Lane, Middlesbrough, TS5 4AR Asking Price £85,000 EPC D Ideal for first time buyers and investors alike. This spacious property offers versatile and well presented accommodation over two floors with close links to the A66 & Close links to the A66 & A19. A19, ideal for commuting. Upon entry you will be greeted by a fresh airy hallway leading to an ample open plan dinning/reception room. The reception room benefits from a large bay window and the dining room has French doors leading to the rear garden. These features make this property bright and welcoming, ideal for modern family living. Leading on from the hall way you will find a spacious galley kitchen and breakfast room. The first floor boasts two double bedrooms and an excellent single room and is completed by a modern family bathroom. Externally this property has a low maintenance front garden and a private rear garden with a gated patio area perfect for entertaining. ***SOLD WITH NO ONWARD CHAIN*** EARLY VIEWINGS RECOMMENDED TO AVOID DISAPPOINTMENT. https://www.bridgfords.co.uk https://www.bridgfords.co.uk Viewing arrangement by appointment 01642 227827 [email protected] Bridgfords, 141 Linthorpe Road, Middlesbrough, TS1 2JR Interested parties should satisfy themselves, by inspection or otherwise as to the accuracy of the description given and any floor plans shown in these property details. All measurements, distances and areas listed are approximate. Fixtures, fittings and other items are NOT included unless specified in these details. Please note that any services, heating systems, or appliances have not been tested and no warranty can be given or implied as to their working order. -

Our Services for You Welcome to Your Service Guide

Our services for you Welcome to your service guide All of us at Thirteen are looking You might remember that we sent you forward to another busy year some information last year to get your working for you. opinions about planned changes to the way your landlord and Thirteen are This guide brings you details of services structured. We’re aiming to simplify how that are available and improvements we we’re organised and to bring all are making. landlords in the group together to form one organisation called Thirteen. You’ll find information about our Our original aim was to do this by April self-service website, customer services, this year but we’re now working to repairs, home improvements, building complete this process between July new homes, services that are available and September. This means that your for you, your neighbourhood officer, and landlord will stay the same for a little some useful contact details. while longer but we’ll let you know more about this process later in the year. We have also been listening to feedback from tenants, leaseholders and If you have any thoughts about how we customers and as a result, many can improve what we do for you, please improvements to our services are get in touch. underway, with more planned throughout the year. Best wishes Ian Wardle Group Chief Executive On behalf of everyone at Thirteen 2 3 Making things easier for you - Contacting customer services Thirteen self-service 24/7 You can log onto Thirteen’s We’re working on the next phase of Contacting Thirteen couldn’t Improving customer services self-service website to carry our self-service website which will have be easier. -

Local Area Maps

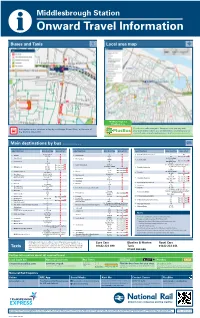

Middlesbrough Station i Onward Travel Information Buses and Taxis Local area map Middlesbrough is a PlusBus area. Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2018 & also map data © OpenStreetMap contributors, CC BY-SA Rail replacement services at lay-by on Bridge Street West, at the rear of PlusBus is a discount price ‘bus pass’ that you buy with your train ticket. It gives you unlimited bus travel around your the Station (Stand W) chosen town, on participating buses. Visit www.plusbus.info Main destinations by bus (Data correct at July 2019) DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP 12, 13, 13A, 14 H 8 M { Teesside Industrial Estate # 17 J { Acklam { Netherfields 17, 17A J 5, 5A N X8 Bus Stn Stand 18 { Beechwood 29 K 63 K { Normanby # 36, 37, 38 (alight 39 A 64A## L { Teesside Park bus on 16 { Berwick Hills 8 M 39 A Middlesbrough Bus Stn Stand 5, 5A, 9 N 8 M Road) 36 Bus Stn Stand 16 { North Ormesby # 5, 5A, 9 N 10 - 15 minutes walk from this Station 62, 62A++, 64A## L via Albert Road (see maps) { Billingham ^ X9, X10 Bus Stn Stand 18 { Teesside University X8 18 8 M 34, 34A 21 Bus Stn Stand Bus Stn Stand 5, 5A, 9 N 8 M 37, 38 Bus Stn Stand 16 { Brambles Farm # { Norton 62, 62A++, 64A## L 62, 62A++ L X10 18 { Teesville Bus Stn Stand 64, 64A Bus Stn Stand 3 { Brookfield 12, 13, 13A, 14 H 28, 28A, 29 K { Nunthorpe ^ 17A J { Coulby Newham 10, 12, 13, 13A H 5, 5A N 36, 37, 38 Bus Stn Stand 16 Dormanstown # 62, 62A++ L 63 K { Thornaby Station ^ { Ormesby # 17 28, -

Middlesbrough Town Centre Stand Information M 8 N H K L

Middlesbrough Town Centre Stand Information Finding the right bus stand for your journey MIDDLESBROUGH HOUSE (Corporation Road) CLEVELAND CENTRE (Grange Road) 9, 39 North Ormesby, Berwick Hills, Park End, Priestfields, Ormesby, No Public Services (Road Temporarily Closed) A Overfields O B No Public Services P No Public Services (Road Temporarily Closed) 13B C (Longlands, Tollesby, Acklam, Brookfield, Hemlington) Q No Public Services (Road Temporarily Closed) No Public Services D R No Public Services (Road Temporarily Closed) E No Public Services No Public Services (Road Temporarily Closed) 9, 39 S F Middlesbrough Bus Station MIDDLESBROUGH TOWN HALL (Albert Road) MIDDLESBROUGH TOWN HALL (Corporation Road) No Public Services No Public Services T G MIDDLESBROUGH STATION MIDDLESBROUGH TOWN HALL (Albert Road) 10, 12, 13, 13A, 14 U No Public Services Longlands, Linthorpe, Tollesby, West Lane Hospital, H James Cook University Hospital, Easterside, Marton Manor, Acklam, Trimdon Avenue, Brookfield, Stainton, Hemlington, Coulby Newham V No Public Services 17, 17A J Linthorpe, Acklam, Thornaby, Ingleby Barwick, Yarm, Eaglescliffe W Rail Replacement Services 28, 28A, 29, 63 Linthorpe, Grove Hill, Saltersgill, Longlands, 9, 39 James Cook University Hospital, Easterside, Marton Manor, Marton, X Middlesbrough Bus Station K Nunthorpe, Guisborough, Charltons, Boosbeck, Lingdale, Great Ayton, Stokesley, Ormesby, Normanby, Eston, Wilton, MIDDLESBROUGH BUS STATION (Brentnall Street: Temporary Stop) Redcar Primary Care Hospital, Lakes Estate, Redcar 62, 64A -

Trimdon Avenue, Baldoon Sands . Union Street . Middlesbrough Via

Trimdon Avenue, Baldoon Sands l Union Street l Middlesbrough via West Lane 14 via Baldoon Sands, Trimdon Avenue, Acklam Road, Longford Street, Union Street, Hartington Road, Brentnall Street, Middlesbrough Bus Station. MONDAY TO FRIDAY S NS S NS t Trimdon Avenue Baldoon Sands 0615 0645 0707 0736 0801 0840 0917 47 17 1447 1526 1556 1626 1631 1656 1726 1731 a l y i n r t s 0 e e Acklam Coronation 0621 0651 0713 0747 0812 0854 0926 56 26 1456 1535 1605 1635 1640 1705 1735 1740 n n h v 3 i t u e West Lane Hospital 0627 0657 0719 0755 0822 0902 0934 04 34 1504 1543 1613 1643 1648 1713 1743 1748 m Middlesbrough Bus Stn arrive 0636 0706 0728 0808 0837 0912 0944 14 44 1514 1553 1623 1653 1658 1723 1753 1758 disability helpdesk y Trimdon Avenue Baldoon Sands 1756 1822 1910 10 2210 2325 l l Monday to Friday 9:00am to 4:30pm Fax: 0191 566 0230 r i n Acklam Coronation 1805 1831 1917 17 2217 2332 t t e u n a Call: 0191 566 0248 (TypeTalk enabled) h West Lane Hospital 1811 1837 1923 23 2223 2338 u t o Email: [email protected] Middlesbrough Bus Stn arrive 1821 1847 1930 h 30 2230 2345 SATURDAY Trimdon Avenue Baldoon Sands 0612 0719 0749 0819 0849 0919 0949 1017 y y s a a a Changes to Service 14 from Sunday 17 February 2019 d Acklam Coronation 0617 0728 0758 0828 0858 0928 0958 1026 d i n r n e West Lane Hospital 0625 0734 0804 0834 0904 0934 1004 1034 F o To assist reliability, there are some minor changes to morning h t o M Middlesbrough Bus Stn arrive 0633 0744 0814 0844 0914 0944 1014 1044 t arrivals in Middlesbrough, and evening trips are slightly retimed. -

Middlesbrough Local Development Framework

MIDDLESBROUGH LOCAL DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK REGENERATION DEVELOPMENT PLAN DOCUMENT ADOPTED FEBRUARY 2009 CONTENTS Section Page 1 BACKGROUND 3 2 CONFORMITY ISSUES 7 3 GREATER MIDDLEHAVEN 10 4 GREATER HEMLINGTON 21 5 INNER MIDDLESBROUGH OLDER HOUSING 29 6 COMPETITIVE BUSINESS 41 INFRASTRUCTURE 7 REVITALISING THE HOUSING MARKET 48 8 A 21ST CENTURY RETAIL AND 55 LEISURE CENTRE 9 A REGIONAL CENTRE FOR EDUCATION, 70 HEALTH AND CULTURE 10 CONNECTING MIDDLESBROUGH 72 APPENDIX A IMPLEMENTATION FRAMEWORK 78 APPENDIX B MONITORING FRAMEWORK 83 APPENDIX C SUPERSEDED POLICIES 87 MIDDLESBROUGH LOCAL DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK REGENERATION DEVELOPMENT PLAN ADOPTED 1 LIST OF POLICIES Policy Page Policy Page REG1 GREATER MIDDLEHAVEN – PHASING 12 REG20 PRINCIPAL USE SECTORS 56 REG2 GREATER MIDDLEHAVEN – 14 REG21 PRIMARY SHOPPING FRONTAGE 57 DEVELOPMENT AND DESIGN PRINCIPLES REG22 CANNON PARK SECTOR 59 REG3 GREATER MIDDLEHAVEN – 16 TRANSPORT INFRASTRUCTURE REG23 MIDDLEHAVEN SECTOR 60 REG4 HEMLINGTON GRANGE – 23 REG24 SOUTHERN SECTOR 62 DEVELOPMENT PRINCIPLES REG25 CENTRE SQUARE EAST 64 REG5 HEMLINGTON GRANGE – 25 EMPLOYMENT USES REG26 GURNEY STREET TRIANGLE 65 REG6 GREATER HEMLINGTON – 26 REG27 MIDDLESBROUGH LEISURE PARK 66 TRANSPORT INFRASTRUCTURE REG28 DISTRICT CENTRES 67 REG7 HEMLINGTON REGENERATION AREA 27 REG29 LOCAL CENTRES 67 REG8 GRESHAM/JEWELS STREET AREA 33 REG30 NEIGHBOURHOOD CENTRES 68 REG9 ABINGDON 35 REG31 PRISSICK BASE 69 REG10 NORTH ORMESBY 36 REG32 ST LUKE'S HOSPITAL 71 REG11 GROVE HILL 37 REG33 CARGO FLEET MEDICAL CENTRE 71 REG12 EMPLOYMENT ALLOCATIONS -

14 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

14 bus time schedule & line map 14 Brookƒeld - Middlesbrough View In Website Mode The 14 bus line (Brookƒeld - Middlesbrough) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Brookƒeld: 6:45 AM - 11:05 PM (2) Middlesbrough: 6:15 AM - 11:25 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 14 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 14 bus arriving. Direction: Brookƒeld 14 bus Time Schedule 26 stops Brookƒeld Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 8:50 AM - 11:05 PM Monday 6:45 AM - 11:05 PM Bus Station Stand 13, Middlesbrough Unit 5/5A Captain Cook Square, Middlesbrough Tuesday 6:45 AM - 11:05 PM Brentnall Street, Middlesbrough Wednesday 6:45 AM - 11:05 PM Brentnall Street, Middlesbrough Thursday 6:45 AM - 11:05 PM Town Hall, Middlesbrough Friday 6:45 AM - 11:05 PM 73-75 Albert Road, Middlesbrough Saturday 7:50 AM - 11:05 PM Amber Street, Middlesbrough Borough Road, Middlesbrough Parkville Care Centre, Newport 14 bus Info Glebe Road, Newport Direction: Brookƒeld Wylam Street, Middlesbrough Stops: 26 Trip Duration: 24 min Parliament Road, Newport Line Summary: Bus Station Stand 13, Middlesbrough, Brentnall Street, Middlesbrough, Leinster Road, Ayresome Town Hall, Middlesbrough, Amber Street, Leinster Road, Middlesbrough Middlesbrough, Parkville Care Centre, Newport, Glebe Road, Newport, Parliament Road, Newport, Liverton Avenue, Ayresome Leinster Road, Ayresome, Liverton Avenue, Acklam Road, Middlesbrough Ayresome, Barnaby Avenue, Ayresome, West Lane Hospital, Ayresome, Springƒeld Road, Linthorpe, Barnaby Avenue, -

Speech and Language Therapy Service for Children with Mild / Moderate Speech Language and Communication Needs in Middlesbrough

SPEECH AND LANGUAGE THERAPY SERVICE FOR CHILDREN WITH MILD / MODERATE SPEECH LANGUAGE AND COMMUNICATION NEEDS IN MIDDLESBROUGH PERFORMANCE REPORT QUARTER 4 13/14 Nikki Joyce Paediatric SLT Service Manager The information contained within this report was pulled from SystmOne on 25th April 2014 following the Easter holiday. All contacts for 1st January to 31st March 2014 were inputted and reportable by this date. All information contained within this report (with the exception of the new referrals as the initial assessment is a health funded contact and, until seen and assessed, the children do not have a diagnosis) relates to children with a diagnosed mild / moderate speech, language or communication need. All children with health needs are excluded from this report. All children with Redcar and Cleveland postcodes are excluded from this report. All Middlesbrough postcodes are included – where children with a Middlesbrough postcode attend a Redcar and Cleveland School (Nunthorpe especially) – data for that school is included. All children included in this report have a diagnosis of either a speech or language DELAY or a mild / moderate general communication DELAY. All disorder diagnoses are excluded from this report as disorder diagnoses would be part of the Specialist Health Funded SLT provision. NB staff funded by health also see children in homes, schools, daycare and clinic settings. Most of the data relates to the number of individual children seen. A child may be seen more than once in a quarter (for example a 6 week block of once weekly speech sound therapy) and this is the number of CONTACTS. Children are allocated the number of sessions as agreed in Part 6 of the contract according to age and diagnosis / aim of therapy. -

Local Resident's Submissions to the Middlesbrough Borough Council

Local resident’s submissions to the Middlesbrough Borough Council electoral review. This PDF document contains 35 submissions from local residents. Some versions of Adobe allow the viewer to move quickly between bookmarks. Click on the submission you would like to view. If you are not taken to that page, please scroll through the document. Gregory, Eleanor From: anitacanderson Sent: 12 February 2013 22:46 To: Pascoe, Mark Subject: Marton West Boundary change proposals Dear Mr. Pascoe I understand that you're the right person to approach with my concerns about the proposal to make the council tax payers at the southern edge of Middlesbrough suffer in the current round of boundary changes. I was shocked to hear that the intention is to combine the disparate areas of Coulby Newham, Marton & Nunthorpe. Whilst you could say there are many similarities between Marton & Nunthorpe, there are major road boundaries between the areas, so it could be dangerous to try to encourage residents to create connections. I'm not sure what your background is, nor whether you're aware of the strength of community feeling that exists in Marton West ward? Residents are hopeful that we may even benefit from cheaper energy prices if the community negotiates successfully. How councillors are supposed to adequately represent such a vast and varied population/property bank, I really can't imagine! In my experience, local councillors are hard-working volunteers who are dedicated to their local area & have sufficient political awareness to ensure they can represent people within the halls of power. They receive very little in the way of expenses or payment for their services.