Competition and Cooperation in Hospital Provision in Middlesbrough, 1918–1948

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ORTHODONTIC COMMISSIONING INTENTIONS (Final - Sept 2018)

CUMBRIA & NORTH EAST - ORTHODONTIC COMMISSIONING INTENTIONS (Final - Sept 2018) Contract size Contract Size Units of Indicative Name of Contract Lot Required premise(s) locaton for contract Orthodontic Activity patient (UOAs) numbers Durham Central Accessible location(s) within Central Durham (ie Neville's Cross/Elvet/Gilesgate) 14,100 627 Durham North West Accessible location(s) within North West Durham (ie Stanley/Tanfield/Consett North) 8,000 356 Bishop Auckland Accessible location(s) within Bishop Auckland 10,000 444 Darlington Accessible location(s) within the Borough of Darlington 9,000 400 Hartlepool Accessible location(s) within the Borough of Hartlepool 8,500 378 Middlesbrough Accessible location(s) within the Borough of Middlesbrough 10,700 476 Redcar and Cleveland Accessible location(s) within the Borough of Redcar & Cleveland, (ie wards of Dormanstown, West Dyke, Longbeck or 9,600 427 St Germains) Stockton-on-Tees Accessible location(s) within the Borough of Stockton on Tees) 16,300 724 Gateshead Accessible location(s) within the Borough of Gateshead 10,700 476 South Tyneside Accessible location(s) within the Borough of South Tyneside 7,900 351 Sunderland North Minimum of two sites - 1 x accesible location in Washington, and 1 other, ie Castle, Redhill or Southwick wards 9,000 400 Sunderland South Accessible location(s) South of River Wear (City Centre location, ie Millfield, Hendon, St Michael's wards) 16,000 711 Northumberland Central Accessible location(s) within Central Northumberland, ie Ashington. 9,000 400 Northumberland -

674 Mac Private Uesidents

674 MAC PRIVATE UESIDENTS. (NORTH AND EAST RIDJNGS l'lcLansborough Joseph Wm. Tile;y, Malcolm Percy S. 3 Holbeck road, Ma.rshall Rev. James McCall M.A. The Poplars, Ooatham, Redcar Scarborough u~ctury, t..roft, Varlingtoa N:cLaren Frederic Donuld, 28 Nor-. Maley Mrs. 24 Scarborough rd. Filey Marshal} A. 5 l::louthcliff rd. Withern- wood; Beverley Malim Rev. "\V. G., B.A. Kilverstone l!ea, .l:l.uH McLa.uchlan J o .. eph, 9 !me;; on terrace, villa, Scalby road, Scarborough Mar.s.bal! AlfreJ, 7 Hemy ~otreet, Linthorpe road, Middlesbrough Malley Horace William R. 2 LindPn Loat.bam, Redcar McLaughlin George, 219 Prospect rd. grove, Linthorpe, Middlesbrough Marshall C.J. 12 Grove Hill rd.Bevrly Scar borough Mallin J oseph James, Ewin house, ..\l.arshall Erskine H. 7 1rafalgar s~. McLean Samuel Moore, 16 Trinity Grove hill, Middlesbrou!rh l::lcarborough road, Bridlington . :Mallin Mrs. J oseph, 85 Douglas ter. Marshall l'. Herbert, West par.-, .M:aclennan Daniel, 2 Brookside, Borough road west, Middle:>brongh \)'est road, Loftus Croydon road, Middlesbrough Mu1linder Rev. Dacre, Scorton,Drlngtn Mar.shall Frederick William, Sherbutt .MacLeod John Farquhar M.B. 71 Mallinson Miss, West lane,Hedon,Hull ho. Napham rd. Pock.lington, York ~ormanby road, South Bank Yallory Geo. The Fields, Nunthorpe M.arshall George, Hmderwell Macleod Mrs.. 8 Newbegin, Beverley Mallory Mrs. 1 Carlton st.Bridlington Marshall J.Terrace ho.Burstwick,Hull McLoughry James Wilson, Avondale, Mallory Mrs. Uppleby, Easingwold Marsh all John, 1'he Poplars, Croh, Thornfield rd. Linthorpe,Middlsbro' Mallory Richard Watson, South side, Da.rlingt-on McMahon Rev. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The development of education in the North Ridings of Yorkshire 1902 - 1939 Jennings, E. How to cite: Jennings, E. (1965) The development of education in the North Ridings of Yorkshire 1902 - 1939, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9965/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Abstract of M. Ed. thesis submitted by B. Jennings entitled "The Development of Education in the North Riding of Yorkshire 1902 - 1939" The aim of this work is to describe the growth of the educational system in a local authority area. The education acts, regulations of the Board and the educational theories of the period are detailed together with their effect on the national system. Local conditions of geograpliy and industry are also described in so far as they affected education in the North Riding of Yorkshire and resulted in the creation of an educational system characteristic of the area. -

Middlesbrough Housing Opportunities

Middlesbrough Housing Conference 2019 investmiddlesbrough.co.uk Welcome to Middlesbrough Top 10 city in Europe One of the strongest A strategy for the for growth strategy consumer growth rates city centre to drive (fDi Magazine) in the UK urban living (2018 UK Consumer Powerhouse report) £22.6million TeesAMP £250million development Significant improvements development to attract to make Middlesbrough to public transport to world-class manufacturing the digital city of the UK enhance connectivity, businesses including a direct service to London A growing population, with A well-considered Award-winning demand for middle and Local Plan university and college upper-market properties provide a talent pipeline that stays in the area My mission is to make Middlesbrough the place to be: to do business, to visit and to live. We’re committing millions of pounds to growing key sectors like digital and advanced manufacturing, to drive high-turnover businesses into the area, create jobs for local people and encourage people to move here. It’s vital that Middlesbrough has housing stock to meet the demands of our growing population, from high-rise apartments in the city centre to high quality affordable housing, and middle and upper-market suburban properties. We have numerous sites primed for investment, and I invite you to be part of Middlesbrough’s future. Andy Preston Elected Mayor of Middlesbrough Housing Growth in Middlesbrough Borough Boundary Planning Permission - Not On Site Planning Permission - Under Construction Allocated Site / Development -

Middlesbrough Boundary Special Protection Area Potential Special

Middlesbrough Green and Blue Infrastructure Strategy Middlesbrough Council Middlesbrough Cargo Fleet Stockton-on-Tees Newport North Ormesby Brambles Farm Grove Hill Pallister Thorntree Town Farm Marton Grove Berwick Hills Linthorpe Whinney Banks Beechwood Ormesby Park End Easterside Redcar and Acklam Cleveland Marton Brookfield Nunthorpe Hemlington Coulby Newham Stainton Thornton Hambleton 0 1 2 F km Map scale 1:40,000 @ A3 Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2020 CB:KC EB:Chamberlain_K LUC 11038_001_FIG_2_2_r0_A3P 08/06/2020 Source: OS, NE, MC Figure 2.2: Biodiversity assets in and around Middlesbrough Middlesbrough boundary Local Nature Reserve Special Protection Area Watercourse Potential Special Protection Area Priority Habitat Inventory Site of Special Scientific Interest Deciduous woodland Ramsar Mudflats Proposed Ramsar No main habitat but additional habitats present Ancient woodland Traditional orchard Local Wildlife Site Middlesbrough Green and Blue Infrastructure Strategy Middlesbrough Council Middlesbrough Cargo Fleet Stockton-on-Tees Newport North Ormesby Brambles Farm Grove Hill Pallister Thorntree Town Farm Marton Grove Berwick Hills Linthorpe Whinney Banks Beechwood Ormesby Park End Easterside Redcar and Acklam Cleveland Marton Brookfield Nunthorpe Hemlington Coulby Newham Stainton Thornton Hambleton 0 1 2 F km Map scale 1:40,000 @ A3 Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2020 CB:KC EB:Chamberlain_K LUC 11038_001_FIG_2_3_r0_A3P 29/06/2020 Source: OS, NE, EA, MC Figure 2.3: Ecological Connection Opportunities in Middlesbrough Middlesbrough boundary Working With Natural Processes - WWNP (Environment Agency) Watercourse Riparian woodland potential Habitat Networks - Combined Habitats (Natural England) Floodplain woodland potential Network Enhancement Zone 1 Floodplain reconnection potential Network Enhancement Zone 2 Network Expansion Zone. -

Doxford Walk, Hemlington, Middlesbrough, TS8 9JD

Doxford Walk, Hemlington, Middlesbrough, TS8 9JD One Bedroom Apartment | Spacious Rooms Throughout With Ample Storage | Recently Decorated | Situated Near Hemlington Lake Gas Central Heating & Double Glazed | Ideal For Downsizing Or Rental Investment | Communal Garden | 110 Years Lease Offers In Region Of: £40,000 Doxford Walk, Hemlington, BATHROOM Middlesbrough, TS8 9JD 2.01m (6' 7") x 1.88m (6' 2") Hunters offer For Sale this SPACIOUS one bedroomed apartment situated near Hemlington Lake. The property would make an ideal investment purchase or for those looking to downsize. It benefits from fresh decoration and offers a lease of 110 years. The maintenance and service charges are approximately £20 per month in total. The property is ground floor and benefits from gas central heating, double glazing and a communal garden. Worth a viewing if you're looking for a cosy place of your own or an investment property. Hunters, Teesside - 01642 224366 GARDEN HALL LEASEHOLD INFORMATION LEASE DETAILS - 110 YEARS ON LEASE £20.03 PER MONTH TO COVER GROUND RENT, MAINTAINANCE AND INSURANCE LOUNGE Management company is Thirteen Group - 01642 4.23m (13' 11") x 3.13m (10' 3") 261120 IMPORTANT INFORMATION N.B. Under the terms of the1979 Estate Agents Act, KITCHEN we are obliged to inform prospective purchasers 3.21m (10' 6") x 2.10m (6' 11") that the vendor of this property is an employee of Hunters Property Franchise Group. THINKING OF SELLING? DOUBLE BEDROOM If you are thinking of selling your home or just 3.83m (12' 7") x 3.13m (10' 3") curious to discover the value of your property, Hunters would be pleased to provide free, no obligation sales and marketing advice. -

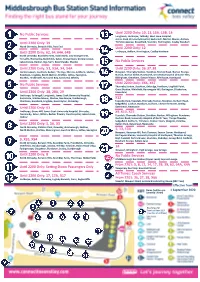

Middlesbrough Bus Station

No Public Services Until 2200 Only: 10, 13, 13A, 13B, 14 Longlands, Linthorpe, Tollesby, West Lane Hospital, James Cook University Hospital, Easterside, Marton Manor, Acklam, Until 2200 Only: 39 Trimdon Avenue, Brookfield, Stainton, Hemlington, Coulby Newham North Ormesby, Berwick Hills, Park End Until 2200 Only: 12 Until 2200 Only: 62, 64, 64A, 64B Linthorpe, Acklam, Hemlington, Coulby Newham North Ormesby, Brambles Farm, South Bank, Low Grange Farm, Teesville, Normanby, Bankfields, Eston, Grangetown, Dormanstown, Lakes Estate, Redcar, Ings Farm, New Marske, Marske No Public Services Until 2200 Only: X3, X3A, X4, X4A Until 2200 Only: 36, 37, 38 Dormanstown, Coatham, Redcar, The Ings, Marske, Saltburn, Skelton, Newport, Thornaby Station, Stockton, Norton Road, Norton Grange, Boosbeck, Lingdale, North Skelton, Brotton, Loftus, Easington, Norton, Norton Glebe, Roseworth, University Hospital of North Tees, Staithes, Hinderwell, Runswick Bay, Sandsend, Whitby Billingham, Greatham, Owton Manor, Rift House, Hartlepool No Public Services Until 2200 Only: X66, X67 Thornaby Station, Stockton, Oxbridge, Hartburn, Lingfield Point, Great Burdon, Whinfield, Harrowgate Hill, Darlington, (Cockerton, Until 2200 Only: 28, 28A, 29 Faverdale) Linthorpe, Saltersgill, Longlands, James Cook University Hospital, Easterside, Marton Manor, Marton, Nunthorpe, Guisborough, X12 Charltons, Boosbeck, Lingdale, Great Ayton, Stokesley Teesside Park, Teesdale, Thornaby Station, Stockton, Durham Road, Sedgefield, Coxhoe, Bowburn, Durham, Chester-le-Street, Birtley, Until -

100% Prime Retail Unit Let to Arcadia Group for a Further 22 Years 7 Months

100% PRIME RETAIL UNIT LET TO ARCADIA GROUP FOR A FURTHER 22 YEARS 7 MONTHS 62A, 64 and 66 Linthorpe Road & 1 Corporation Street, Middlesbrough TS1 1RA EXECUTIVE SUMMARY n 100% prime location amongst leading national retailers n Immediately opposite the recently opened Flannels, Sports Direct and USC units n Let for a further 22 years and 7 months to the Arcadia Group n Passing rent of £174,000 per annum n Freehold n Asking price - £3.11M (Three million, one hundred and ten thousand pounds) excluding VAT reflecting a net initial yield of 5.25% after purchasers’ costs at 6.46% 100% PRIME RETAIL UNIT LET TO ARCADIA GROUP FOR A FURTHER 22 YEARS 7 MONTHS LOCATION Middlesbrough is the economic and The economy within Middlesbrough is administrative centre for Teesside. The town based predominantly on manufacturing, is located approximately 40 miles south of chemical production, and shipping with Newcastle, 12 miles east of Darlington and Tees Port providing major employment 60 miles north east of Leeds. opportunities. Tees Port is currently the 3rd Middlesbrough has a population of largest port in the UK and one of the 10th 138,900 (Middlesbrough Council 2016) largest in Western Europe handling over with a wider catchment population of 56m tons of domestic international cargo. 662,600 within a radius of 12 miles. Middlesbrough also has a thriving University with a student body in excess The town is easily accessible from the A66 of 24,000 contributing over £124m per leading to the A19 and A1(M). By rail the annum to the Middlesbrough economy. -

The Council of the Borough of Middlesbrough (Woodlands Road / Southfield Road / Fern Street) Temporary Traffic Regulation Order 2020

THE COUNCIL OF THE BOROUGH OF MIDDLESBROUGH (WOODLANDS ROAD / SOUTHFIELD ROAD / FERN STREET) TEMPORARY TRAFFIC REGULATION ORDER 2020 NOTICE is hereby given that on 21st April 2020 Middlesbrough Council made an Order which prevents vehicles from using the lengths of road set out below due to redevelopment / improvement works by Teesside University taking place on or near the road because of the likelihood of danger to the public. Access for pedestrians and the emergency services will be maintained at all times. Access will also be provided for vehicles used in connection with maintenance and works carried out by statutory undertakers. The roads will be closed during the programmed dates shown below for up to 18 months or until the works have been completed and there is no longer a danger to the public. If the works are not completed within 18 months, the Order may be extended with the approval of the Secretary of State. Dated 23rd April 2020 Charlotte Benjamin Director of Legal and Governance Services Town Hall Middlesbrough TS1 9FX Location Description Programmed Dates Woodlands Road from its junctions with the southern kerbline of Clarendon 8/6/20 - 10/8/20 Road to the northern kerbline of Southfield Road. Southfield Road from a point 5m west of its junction with the western 20/7/20 - 10/8/20 kerbline of Woodlands Road to a point 15m east of its junction with the eastern kerbline of Woodlands Road. Southfield Road (northern parking bays only) from a point 6m west of its 27/4/20 - 10/8/20 junction with the western kerbline of Fern Street for a distance of 18m in a westerly direction. -

13B Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

13B bus time schedule & line map 13B Newham Grange - Hemlington View In Website Mode The 13B bus line Newham Grange - Hemlington has one route. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Hemlington: 6:47 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 13B bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 13B bus arriving. Direction: Hemlington 13B bus Time Schedule 66 stops Hemlington Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 6:47 AM Nightingale Drive, Newham Grange Hebburn Road, Stockton-On-Tees Tuesday 6:47 AM Humbledon Road, Newham Grange Wednesday 6:47 AM Humbledon Road, Stockton-On-Tees Thursday 6:47 AM The Vale, Newham Grange Friday 6:47 AM Darlington Lane, Stockton-On-Tees Saturday Not Operational Norwich Avenue, Elm Tree Clover Court, Stockton-On-Tees Felton Lane, Fairƒeld Darlington Back Lane, Stockton-On-Tees 13B bus Info Direction: Hemlington Fordwell Road, Fairƒeld Stops: 66 Trip Duration: 81 min Torwell Drive, Fairƒeld Line Summary: Nightingale Drive, Newham Grange, Rimswell Road, Stockton-On-Tees Humbledon Road, Newham Grange, The Vale, Newham Grange, Norwich Avenue, Elm Tree, Felton Rimswell Road South End, Fairƒeld Lane, Fairƒeld, Fordwell Road, Fairƒeld, Torwell Drive, Fairƒeld, Rimswell Road South End, Fairƒeld, The The Rimswell, Fairƒeld Rimswell, Fairƒeld, Bishopton Court, Fairƒeld, The Avenue, Fairƒeld, Castle Close, Elm Tree, Sixth Form Bishopton Court, Fairƒeld College, Newtown, Loweswater Crescent, St Mark's Close, Stockton-On-Tees Grangeƒeld, Spennithorne Road, Grangeƒeld, Ambulance -

Ct12d4.Qxd (Page 1)

Coulby Newham z Hemlington z Middlesbrough via Acklam Road and Linthorpe 12 via Parkway Centre, Dalby Way, Stainton Way, Cass House Road, Viewley Centre Road, Hemlington Hall Road, Viewley Hill Avenue, Hemlington Lane, Acklam Road, Cambridge Road, Orchard Road,The Avenue, Linthorpe Road, Grange Road,Albert Road, Borough Road, Middlesbrough Bus Station. MONDAY TO FRIDAY ****** Service number 12 12 12 12 12 12 12 12 12 12 12 12 Coulby Newham, Parkway Centre 0645 0655 0705 0715 0725 0735 0745 0755 0805 0815 0825 0835 Hemlington,The Gables 0648 0658 0708 0718 0728 0738 0748 0758 0808 0818 0828 0838 Hemlington Shops 0655 0705 0715 0725 0735 0745 0755 0805 0815 0825 0835 0845 Acklam,The Coronation 0702 0712 0722 0732 0742 0752 0802 0812 0822 0832 0842 0852 Linthorpe Village 0708 0718 0728 0738 0748 0758 0815 0825 0835 0845 0855 0901 Middlesbrough Bus Station 0719 0729 0739 0749 0759 0809 0826 0836 0846 0856 0906 0912 Service number 12 12 12 12 12 12 12 12 12 Coulby Newham, Parkway Centre 0845 55 05 15 25 35 45 1745 1805 Hemlington,The Gables 0848 58 08 18 28 38 48 1748 1808 Hemlington Shops 0855 05 15 25 35 45 55 1755 1815 mins at Acklam,The Coronation 0902 12 22 32 42 52 02 until 1802 1822 Linthorpe Village 0908 18 28 38 48 58 08 1808 1828 then every Middlesbrough Bus Station 0919 10 29 39 49 59 09 19 1819 1839 Service number 12 12 12 12 12 For travel Coulby Newham, Parkway Centre 1825 1843 13 43 2313 information contact Hemlington,The Gables 1828 1846 16 46 2316 Traveline on DDA Aware Hemlington Shops 1835 1853 23 53 2323 Please contact us if you have difficulty reading this Acklam,The Coronation 1842 1859 mins at 29 59 2329 0870 until document. -

The Council of the Borough of Middlesbrough (South Area) (Waiting and Loading and Parking Places) (Consolidation) Order 2006

THE COUNCIL OF THE BOROUGH OF MIDDLESBROUGH (SOUTH AREA) (WAITING AND LOADING AND PARKING PLACES) (CONSOLIDATION) ORDER 2006 The Council of the Borough of Middlesbrough ('the Council') in exercise of its powers under Sections 1(1) and(2), 2(1) to (3) 3(2) 32(1) 35 45 46 46A 47 49 51 and 53 and Part IV of Schedule 9 to the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984, as amended, ('the Act') and of all other enabling powers and after consultation with the Chief Officer of Police in accordance with Part III of Schedule 9 to the Act, hereby makes the following Order: DEFINITIONS In this Order all expressions except as otherwise herein provided shall have the meanings assigned to them by the Act. “disabled person's badge” has the same meaning as in the Disabled Persons (Badges for Motor Vehicles) (England) Regulations 2000 “disabled person's vehicle” means a vehicle lawfully displaying a disabled person's badge. “driver” in relation to a vehicle waiting in a parking place, means the person driving the vehicle at the time it was left in the parking place. “dual purpose vehicle” has the same meaning as in Regulation 3 of the Road Vehicles (Construction and Use) Regulations 1986, as amended. “freehold owner” means the owner of premises used for business purposes situated adjacent to a permit parking place more particularly set out in Schedule 10 to this Order. “goods vehicle” means a motor vehicle which is constructed or adapted for use for the carriage of goods or burden of any description and which has an unladen weight not exceeding 7.5 tonnes and is not drawing a trailer.