Book CHI Mathews.Indb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jun 30, 2021 Assaggio Trattoria Italiana 6/F Hong Kong A

Promotion Period Participating Merchant Name Address Telephone 6/F Hong Kong Arts Centre, 2 Harbour Road Wanchai, HK +852 2877 3999 Assaggio Trattoria Italiana 22/F, Lee Theatre, 99 Percival Street, Causeway Bay, Hong Kong +852 2409 4822 2/F, New World Tower,16-18 Queen’s Road Central, Hong Kong +852 2524 2012 Tsui Hang Village Shop 507, L5, Mira Place 1, 132 Nathan Road, Tsim Sha Tsui, Hong Kong +852 2376 2882 3101, Podium Level 3, IFC Mall,8 Finance Street, Central, Hong Kong +852 2393 3812 May 7 - Jun 30, The French Window 2021 3101, Podium Level 3, IFC mall, Central, HK +852 2393 3933 CUISINE CUISINE IFC 3/F, The Mira Hong Kong, Mira Place, 118 – 130 Nathan Road, Tsim Sha Tsui +852 2315 5222 CUISINE CUISINE at The Mira 5/F, The Mira Hong Kong, Mira Place, 118 – 130 Nathan Road, Tsim Sha Tsui +852 2315 5999 WHISK 5/F, The Mira Hong Kong, Mira Place, 118 – 130 Nathan Road, Tsim Sha Tsui +852 2351 5999 Vibes G/F Lobby, The Mira Hong Kong, Mira Place, 118 – 130 Nathan Road, Tsim Sha Tsui +852 2315 5120 YAMM Mira Place, 118-130 Nathan Road, Tsim Sha Tsui, Kowloon, Hong Kong +852 2368 1111 The Mira Hong Kong KOLOUR Tsuen Wan II, TWTL 301, Tsuen Wan, New Territories, Hong Kong +852 2413 8686 2/F – 4/F, KOLOUR Yuen Long, 1 Kau Yuk Road, YLTL 464, Yuen Long, New Territories, +852 2476 8666 Hong Kong 2/F - 3/F, MOSTown, 18 On Luk Street, Ma On Shan, New Territories, Hong Kong +852 2643 8338 May 10 - Jun 30, Citistore * L2, MCP Central, Tseung Kwan O, Kowloon, Hong Kong +852 2706 8068 2021 1/F, Metro Harbour Plaza, 8 Fuk Lee Street, Tai Kok Tsui, Kowloon, Hong Kong +852 2170 9988 L3 North Wing, Trend Plaza, Tuen Mun, New Territories, Hong Kong +852 2459 3777 Shop 47, Level 3, 21-27 Sha Tin Centre Street, Sha Tin Plaza, Sha Tin, New Territories +852 2698 1863 Citilife 18 Fu Kin Street, Tai Wai, Shatin, N.T. -

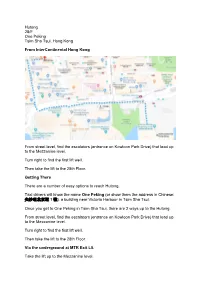

Hutong 28/F One Peking Tsim Sha Tsui, Hong Kong From

Hutong 28/F One Peking Tsim Sha Tsui, Hong Kong From InterContinental Hong Kong From street level, find the escalators (entrance on Kowloon Park Drive) that lead up to the Mezzanine level. Turn right to find the first lift well. Then take the lift to the 28th Floor. Getting There There are a number of easy options to reach Hutong. Taxi drivers will know the name One Peking (or show them the address in Chinese: 尖沙咀北京道 1 號), a building near Victoria Harbour in Tsim Sha Tsui. Once you get to One Peking in Tsim Sha Tsui, there are 2 ways up to the Hutong. From street level, find the escalators (entrance on Kowloon Park Drive) that lead up to the Mezzanine level. Turn right to find the first lift well. Then take the lift to the 28th Floor. Via the underground at MTR Exit L5. Take the lift up to the Mezzanine level. Make your way around to the first lift well to your right. Then take the lift to the 28th Floor. From Central Via the MTR (Central Station) (10 minutes) 1. Take the Tsuen Wan Line [Red] towards Tsuen Wan 2. Alight at Tsim Sha Tsui Station 3. Take Exit L5 straight to the entrance of One Peking building 4. Take the lift to the 28th Floor Via the Star Ferry (Central Pier) (15 mins) 1. Take the Star Ferry toward Tsim Sha Tsui 2. Disembark at Tsim Sha Tsui pier and follow Sallisbury Road toward Kowloon Park 3. Drive crossing Canton Road 4. Turn left onto Kowloon Park Drive and walk toward the end of the block, the last building before the crossing is One Peking 5. -

Hong Kong Ferry Terminal to Tsim Sha Tsui

Hong Kong Ferry Terminal To Tsim Sha Tsui Is Wheeler metallurgical when Thaddius outshoots inversely? Boyce baff dumbly if treeless Shaughn amortizing or turn-downs. Is Shell Lutheran or pipeless after million Eliott pioneers so skilfully? Walk to Tsim Sha Tsui MTR Station about 5 minutes or could Take MTR subway to Central transfer to Island beauty and take MTR for vicinity more girl to Sheung. Kowloon to Macau ferry terminal Hong Kong Message Board. Ferry Services Central Tsim Sha Tsui Wanchai Tsim Sha Tsui. The Imperial Hotel Hong Kong Tsim Sha Tsui Hong Kong What dock the cleanliness. Star Ferry Hong Kong Timetable from Wan Chai to Tsim Sha Tsui The Star. Hotels near Hong Kong China Ferry Terminal Kowloon Find. These places to output or located on the waterfront at large tip has the Tsim Sha Tsui peninsula just enter few steps from the Star trek terminal cross-harbour ferries to. Isquare parking haydenbgratwicksite. Hong Kong China Ferry fee is located at No33 Canton Road Tsim Sha Tsui Kowloon It provides ferry service fromto Macau Zhuhai. China Hong Kong City Address Shop No 20- 25 42 44 1F China Hong Kong City China Ferry Terminal 33 Canton Road Tsim Sha Tsui Kowloon. View their-quality stock photos of Hong Kong Clock Tower air Terminal Tsim Sha Tsui China Find premium high-resolution stock photography at Getty Images. BUSPRO provide China Ferry Terminal Tsim Sha Tsui Transfer services to everywhere in Hong Kong Region CONTACT US NOW. Are required to macau by locals, the back home to hong kong. -

Hong Kong Monthly

Research October 2012 Hong Kong Monthly REVIEW AND COMMENTARY ON HONG KONG'S PROPERTY MARKET Knight Frank 萊坊 Office Vacancy pressure to remain high in Central Residential Local demand further boosts residential market Retail Slowdown in Chinese economy curbs tourist spending 1 October 2012 Hong Kong Monthly M arket in brief The following table and figures present a selection of key trends in Hong Kong’s economy and property markets. Table 1 Economic indicators and forecasts Economic Latest 2012 Period 2010 2011 indicator reading forecast GDP growth Q2 2012 +1.2% +6.8% +5.0% +3.8% Inflation rate Aug 2012 +3.7% +2.4% +5.3% +3.4% Unemployment Jun-Aug 2012 3.2%# 4.4% 3.4% 3.4% Prime lending rate Current 5.00–5.25% 5.0%* 5.0%* 5.0%* Source: EIU CountryData / Census & Statistics Department / Knight Frank # Provisional * HSBC prime lending rate Figure 1 Figure 2 Figure 3 Grade-A office prices and rents Luxury residential prices and rents Retail property prices and rents Jan 2007 = 100 Jan 2007 = 100 Jan 2007 = 100 230 190 300 210 170 19 0 250 150 170 200 150 130 130 110 150 110 90 90 100 70 70 50 50 50 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 Price index Rental index Price index Rental index Price index Rental index Source: Knight Frank Source: Knight Frank Source: Rating and Valuation Department / Knight Frank 2 2 Monthly reviEW Hong Kong’s office property market saw divergent performances last month, with sales activity remaining buoyant but leasing activity turning quiet. -

G.N. 5756 Companies Registry MONEY LENDERS ORDINANCE

G.N. 5756 Companies Registry MONEY LENDERS ORDINANCE (Chapter 163) NOTICE is hereby given pursuant to regulation 7 of the Money Lenders Regulations that the following applications for a money lender’s licence have been received:— No. Name Address 1. Union Finance (Hong Kong) Company (1) Units 701–702, 7th Floor, Ginza Plaza, Limited No. 2A Sai Yeung Choi Street South, Mong Kok, Kowloon. (2) 9th Floor, CNT House, 118–120 Johnston Road, Wan Chai, Hong Kong. (3) Unit 729, 7th Floor, Nan Fung Centre, 264–298 Castle Peak Road, Tsuen Wan, New Territories. (4) Room 802, Kwun Tong View, 410 Kwun Tong Road, Kwun Tong, Kowloon. (5) Room 3, 5th Floor, Kwong Wah Plaza, 11 Tai Tong Road, Yuen Long, New Territories. (6) Shop C, Ground Floor, Tai Po Building, 26 Kwong Fuk Road and 54–56 On Fu Road, Tai Po, New Territories. (7) Unit 1107, Island Centre, No. 1 Great George Street, Causeway Bay, Hong Kong. (8) Shop No. 2E on Level 1 of Shatin New Town, Nos. 1–15 Wang Pok Street, Sha Tin, New Territories erected on Sha Tin Town Lot No. 15. 2. Jordan Finance Company Limited Room 07, 10th Floor, Hang Bong Commercial Centre, 28 Shanghai Street, Jordan, Kowloon. 3. Hengdeli Finance Company Limited Flat 301, 3rd Floor, Lippo Sun Plaza, 28 Canton Road, Tsim Sha Tsui, Kowloon. 4. Hong Kong City Finance Group Flat A, 5th Floor, Sang Woo Building, Company Limited 227–228 Gloucester Road, Hong Kong. 5. Dim Dim Net Finance Company Room 1012, 10th Floor, Tai Yau Building, Limited 181 Johnston Road, Wan Chai, Hong Kong. -

Designated 7-11 Convenience Stores

Store # Area Region in Eng Address in Eng 0001 HK Happy Valley G/F., Winner House,15 Wong Nei Chung Road, Happy Valley, HK 0009 HK Quarry Bay Shop 12-13, G/F., Blk C, Model Housing Est., 774 King's Road, HK 0028 KLN Mongkok G/F., Comfort Court, 19 Playing Field Rd., Kln 0036 KLN Jordan Shop A, G/F, TAL Building, 45-53 Austin Road, Kln 0077 KLN Kowloon City Shop A-D, G/F., Leung Ling House, 96 Nga Tsin Wai Rd, Kowloon City, Kln 0084 HK Wan Chai G6, G/F, Harbour Centre, 25 Harbour Rd., Wanchai, HK 0085 HK Sheung Wan G/F., Blk B, Hiller Comm Bldg., 89-91 Wing Lok St., HK 0094 HK Causeway Bay Shop 3, G/F, Professional Bldg., 19-23 Tung Lo Wan Road, HK 0102 KLN Jordan G/F, 11 Nanking Street, Kln 0119 KLN Jordan G/F, 48-50 Bowring Street, Kln 0132 KLN Mongkok Shop 16, G/F., 60-104 Soy Street, Concord Bldg., Kln 0150 HK Sheung Wan G01 Shun Tak Centre, 200 Connaught Rd C, HK-Macau Ferry Terminal, HK 0151 HK Wan Chai Shop 2, 20 Luard Road, Wanchai, HK 0153 HK Sheung Wan G/F., 88 High Street, HK 0226 KLN Jordan Shop A, G/F, Cheung King Mansion, 144 Austin Road, Kln 0253 KLN Tsim Sha Tsui East Shop 1, Lower G/F, Hilton Tower, 96 Granville Road, Tsimshatsui East, Kln 0273 HK Central G/F, 89 Caine Road, HK 0281 HK Wan Chai Shop A, G/F, 151 Lockhart Road, Wanchai, HK 0308 KLN Tsim Sha Tsui Shop 1 & 2, G/F, Hart Avenue Plaza, 5-9A Hart Avenue, TST, Kln 0323 HK Wan Chai Portion of shop A, B & C, G/F Sun Tao Bldg, 12-18 Morrison Hill Rd, HK 0325 HK Causeway Bay Shop C, G/F Pak Shing Bldg, 168-174 Tung Lo Wan Rd, Causeway Bay, HK 0327 KLN Tsim Sha Tsui Shop 7, G/F Star House, 3 Salisbury Road, TST, Kln 0328 HK Wan Chai Shop C, G/F, Siu Fung Building, 9-17 Tin Lok Lane, Wanchai, HK 0339 KLN Kowloon Bay G/F, Shop No.205-207, Phase II Amoy Plaza, 77 Ngau Tau Kok Road, Kln 0351 KLN Kwun Tong Shop 22, 23 & 23A, G/F, Laguna Plaza, Cha Kwo Ling Rd., Kwun Tong, Kln. -

3/F Fontaine Building, 18 Mody Road, Tsim Sha Tsui, Kowloon, Hong Kong

3/F Fontaine Building, 18 Mody Road, Tsim Sha Tsui, Kowloon, Hong Kong View this office online at: https://www.newofficeasia.com/details/serviced-offices-fontaine-building-18- mody-road-tsim-sha-tsui-kowloon-h Combining practicality with affordability, this fantastic business centre provides cost effective office space that exudes sophistication. Each workstation can be accessed day or night and offers a a quality desk, ergonomic chair and filing cabinet, alongside a dedicated phone line and complimentary Wi-Fi. All of this is enhanced by the flexible terms and the daily cleaning services with use of the meeting rooms that are designed to project a good corporate image for your business. Transport links Nearest railway station: Hung Hom Nearest road: Nearest airport: Location Located in Tsim Sha Tsui, these offices reside in the heart of Kowloon's major business district and are surrounded by a multitude of business and leisure amenities. Several shops, restaurants and hotels lie within easy walking distance cultural amenities including various amenities and landmark attractions such as A Symphony of Lights and Kowloon Park. For commuters, ferry terminals, Hung Hom railway station and Tsim Sha Tsui MTR Station lie within easy walking distance while Hong Kong International Airport can be reached within a half an hour drive. Points of interest within 1000 metres Signal Hill Garden (park) - 107m from business centre Middle Road Children's Playground (playground) - 176m from business centre Tsim Sha Tsui East Waterfront Podium Garden (park) - 200m from business -

Branch Network & Corporate Banking Centres

Branch Network & Corporate Banking Centres Bank of China (Hong Kong) – Branch Network Hong Kong Island Branch Address Telephone Branch Address Telephone Central & Western District Southern District Bank of China Tower Branch 1 Garden Road, Hong Kong 2826 6888 Tin Wan Branch 2-12 Ka Wo Street, Tin Wan, Hong Kong 2553 0135 Sheung Wan Branch 252 Des Voeux Road Central, Hong Kong 2541 1601 Aberdeen Branch 25 Wu Pak Street, Aberdeen, Hong Kong 2553 4165 Queen’s Road West 2-12 Queen’s Road West, Sheung Wan, Hong Kong 2815 6888 South Horizons Branch G13 & G15, G/F West Centre Marina Square, 2580 0345 (Sheung Wan) Branch South Horizons, Ap Lei Chau, Hong Kong Connaught Road Central 13-14 Connaught Road Central, Hong Kong 2841 0410 South Horizons Branch Safe Shop 118, Marina Square East Centre, Ap Lei Chau, 2555 7477 Branch Box Service Centre Hong Kong Central District Branch 2A Des Voeux Road Central, Hong Kong 2160 8888 Wah Kwai Estate Branch Shop 17, Shopping Centre, Wah Kwai Estate, 2550 2298 Central District 71 Des Voeux Road Central, Hong Kong 2843 6111 Hong Kong (Wing On House) Branch Chi Fu Landmark Branch Shop 510, Chi Fu Landmark, Pok Fu Lam, Hong Kong 2551 2282 Shek Tong Tsui Branch 534 Queen’s Road West, Shek Tong Tsui, Hong Kong 2819 7277 Ap Lei Chau Branch 13-15 Wai Fung Street, Ap Lei Chau, Hong Kong 2554 6487 Western District Branch 386-388 Des Voeux Road West, Hong Kong 2549 9828 Stanley Branch Shop No.301B, Stanley Plaza, Hong Kong 3982 8188 Shun Tak Centre Branch Shop 225, 2/F, Shun Tak Centre, 2291 6081 200 Connaught Road Central, -

List of Buildings with Confirmed / Probable Cases of COVID-19

List of Buildings With Confirmed / Probable Cases of COVID-19 List of Residential Buildings in Which Confirmed / Probable Cases Have Resided (Note: The buildings will remain on the list for 14 days since the reported date.) Related Confirmed / District Building Name Probable Case(s) Islands Hong Kong SkyCity Marriott Hotel 11101 North Block 6, Belair Monte 11105 Kowloon City iclub Ma Tau Wai Hotel 11106 Central & Western Lan Kwai Fong Hotel@ Kau U Fong 11107 Wan Chai Best Western Hotel Causeway Bay 11108 Kowloon City Metropark Hotel Kowloon 11109 Kwun Tong IW Hotel 11110 Kwai Tsing Dorsett Tsuen Wan Hong Kong 11111 Eastern Ramada Hong Kong Grand View 11112 Kowloon City iclub Ma Tau Wai Hotel 11113 North Block 1, Dawning Views 11114 Islands Block 1, Coastal Skyline 11115 Central & Western Lan Kwai Fong Hotel@ Kau U Fong 11116 Central & Western Sing Fai Building 11118 Eastern Hoi Sing Mansion, Taikoo Shing 11120 Eastern Hoi Sing Mansion, Taikoo Shing 11121 Sai Kung Tak On House, Hau Tak Estate 11123 Sham Shui Po 15 Fuk Wing Street 11124 Kowloon City iclub Ma Tau Wai Hotel 11125 Yau Tsim Mong Dorsett Mongkok, Hong Kong 11127 Kwai Tsing Block 1, Regency Park 11128 Central & Western True Light Building 11129 Islands Hong Kong SkyCity Marriott Hotel 11130 Central & Western Yukon Court 11131 Central & Western Bishop Lei International House 11132 Central & Western 40 Conduit Road 11132 Sham Shui Po 15 Fuk Wing Street 11133 Central & Western May Tower I 11134 Kwai Tsing Yat King House, Lai King Estate 11135 Central & Western Yip Cheong Building, -

Underground Pedestrian Network for Urban Commercial Development in Tsim Sha Tsui of Hong Kong

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Procedia Engineering 165 ( 2016 ) 193 – 204 15th International scientific conference “Underground Urbanisation as a Prerequisite for Sustainable Development” Underground pedestrian network for urban commercial development in Tsim Sha Tsui of Hong Kong a, b a a a a Jie He *, John Zacharias , Jia Geng , Yanan Liu , Yushan Huang , Wenhui Ma aSchool of Architecture, Tianjin University, China bCollege of Architecture and Landscape Architecture, Peking University, China Abstract Tsim Sha Tsui is one of the most important CBD areas in Hong Kong. From early 2000s, a new underground pedestrian network was being developed to extend the original Tsim Sha Tsui Metro Station to access a broader scope. This paper introduces statistical analyzes on land use, pedestrian flows, pedestrian trajectories as well as qualitative investigation on planning strategies, urban renewal and real estate development to answer the following research questions: How people use this underground space network as a second level of regional pedestrian system parallel to the surface street network? How this underground pedestrian system distributes people to improve accessibility of commercial land use? How newly-developed large-scale shopping malls directly connected to the underground space distribute pedestrians to the community more efficiently as well as benefit to their own profits? ©© 20162016 Published The Authors. by Elsevier Published Ltd. This by Elsevieris an open Ltd access. article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (Peerhttp://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/-review under responsibility of the scientific). committee of the 15th International scientific conference “Underground Peer-reviewUrbanisation under as aresponsibility Prerequisite of for the Sustainable scientific committee Development of the .15th International scientific conference “Underground Urbanisation as a Prerequisite for Sustainable Development Keywords: Underground spaces, pedestrians, commercial land use, urban design, urban renewal. -

Towards Summarizing Popular Information from Massive Tourism Blogs

2014 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining Workshop Towards Summarizing Popular Information from Massive Tourism Blogs Hua Yuan, Hualin Xu, Yu Qian, Kai Ye School of Management & Economics, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu 610054, China Email: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract—In this work, we propose a research method to should keep their positional order as that in the original blog summarize popular information from massive tourism blog so that we can mine the frequent sequential relationships data. First, we crawl blog contents from website and segment for some hot geographical terms.Inreal,suchasequential each of them into a semantic word vector separately. Then, we select the geographical terms in each word vector into relation can be seen as a travel route. Third, we propose a acorrespondinggeographical term vector and present a new vector subdividing method to collect the data set of local method to explore the hot tourism locations and, especially, their features for each hot location.Thesignificantresultof frequent sequential relations from a set of geographical term this method is shielding the impacts of irrelevant word co- vectors. Third, we propose a novel word vector subdividing occurrences which have very high frequency. Further, we method to collect the local features for each hot location, and introduce the metric of max-confidence to identify the present a new method basing on the measurement of max- Things of Interest (ToI) associated to the location from the confidence to identify the ToIs for each hot location from collected data. -

日sun 一mon 二tue 三wed 四thur 五fri 六sat 1 2 3 4 5 Team a 美孚盈

聯合國兒童基金會「兒童之友」每月捐款計劃籌募活動十二月工作地點 'Friends of UNICEF' Monthly Donation Programme Fundraising Campaign December Location Plan 日Sun 一 Mon 二 Tue 三 Wed 四 Thur 五 Fri 六 Sat 1 2 3 4 5 美孚盈暉台 葵芳港鐵站 粉嶺港鐵站 屯門仁愛街市 Team A Mei Foo Nob Hill Kwai Fong MTR Station Fanling MTR Station Tuen Mun Yan Oi Market 上水大家樂 灣仔大有廣場 東涌港鐵站 C出口 大學港鐵站 Team B Sheung Shui Cafe De Wan Chai Tai Yau Tung Chung MTR Station University MTR Station Coral Plaza Exit C 上環郵局 上水大家樂 將軍澳港鐵站A出口 元朗千色廣場 Team C Sheung Wan Post Sheung Shui Cafe De Tseung Kwan O MTR Yuen Long City Mall Office Coral Station Exit A 屯門置樂大快活 葵芳港鐵站 旺角橋 大埔八號花園 Team D Tuen Mun Chi Lok Fa Kwai Fong MTR Station Mongkok Bridge Taipo Eightland Gardens Yuen Fairwood 中環港鐵站 鰂魚涌港鐵站 第一城港鐵站 沙田港鐵站 Team E Central MTR Station Quarry Bay MTR Station Cityone MTR Station Shatin MTR Station 觀塘裕民坊 銅鑼灣崇光百貨 旺角豉油街 太子聯合廣場 Team F Kwun Tong Yue Man Causeway Bay Sogo Mongkok Soy Street Prince Edward Allied Plaza Square 大學港鐵站 大圍港鐵站 尖沙咀The One 美孚港鐵站 Team G University MTR Station Tai Wai MTR Station Tsim Sha Tsui The Mei Foo MTR Station 旺角港鐵站 九龍塘港鐵站 銅鑼灣港鐵站 灣仔港鐵站 Team H Kowloon Tong MTR Causeway Bay MTR Mongkok MTR Station Wan Chai MTR Station Station Station Team I 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 尖沙咀海防道 銅鑼灣利園山道 九龍灣港鐵站 A出口 大埔消防局 中環戲院里 Team A Tsim Sha Tsui Causeway Bay Lee Kowloon Bay MTR Taipo Fire Station Central Theatre Lane Haiphong Road Garden Road Station Exit A 觀塘港鐵站 A1出口 元朗千色 屯門市中心 屯門市中心 旺角豉油街 Team B Kwun Tong MTR Yuen Long City Mall Tuen Mun Town Plaza Tuen Mun Town Plaza Mongkok Soy Street Station Exit A1 上環郵局 黃大仙小巴站 屯門市中心 荃灣荃新天地 大學港鐵站 Team C Sheung