The --Cahuilla Indians

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

People of Snowy Mountain, People of the River: a Multi-Agency Ethnographic Overview and Compendium Relating to Tribes Associated with Clark County, Nevada

Portland State University PDXScholar Anthropology Faculty Publications and Presentations Anthropology 2012 People of Snowy Mountain, People of the River: A Multi-Agency Ethnographic Overview and Compendium Relating to Tribes Associated with Clark County, Nevada Douglas Deur Portland State University, [email protected] Deborah Confer University of Washington Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/anth_fac Part of the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Sustainability Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Deur, Douglas and Confer, Deborah, "People of Snowy Mountain, People of the River: A Multi-Agency Ethnographic Overview and Compendium Relating to Tribes Associated with Clark County, Nevada" (2012). Anthropology Faculty Publications and Presentations. 98. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/anth_fac/98 This Report is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Pacific West Region: Social Science Series National Park Service Publication Number 2012-01 U.S. Department of the Interior PEOPLE OF SNOWY MOUNTAIN, PEOPLE OF THE RIVER: A MULTI-AGENCY ETHNOGRAPHIC OVERVIEW AND COMPENDIUM RELATING TO TRIBES ASSOCIATED WITH CLARK COUNTY, NEVADA 2012 Douglas Deur, Ph.D. and Deborah Confer LAKE MEAD AND BLACK CANYON Doc Searls Photo, Courtesy Wikimedia Commons -

History of Nuwuvi People

History of Nuwuvi People The Nuwuvi, or Southern Paiute peoples (the people), are also known as Nuwu. The Southern Paiute language originates from the uto-aztecan family of languages. Many different dialects are spoken, but there are many similarities between each language. UNLV, and the wider Las Vegas area, stands on Southern Paiute land. Historically, Southern Paiutes were hunter-gatherers and lived in small family units. Prior to colonial influence, their territory spanned across what is today Southeastern California, Southern Nevada, Northern Arizona, and Southern Utah. Within this territory, many of the Paiutes would roam the land moving from place to place. Often there was never really a significant homebase. The Las Vegas Paiute Tribe (LVPT) mentions that, “Outsiders who came to the Paiutes' territory often described the land as harsh, arid and barren; however, the Paiutes developed a culture suited to the diverse land and its resources.” Throughout the history of the Southern Paiute people, there was often peace and calm times. Other than occasional conflicts with nearby tribes, the Southern Paiutes now had to endure conflict from White settlers in the 1800s. Their way of life was now changed with the onset of construction for the Transcontinental railroad and its completion. Among other changes to the land, the LVPT also said, “In 1826, trappers and traders began crossing Paiute land, and these crossings became known in 1829 as the Old Spanish Trail (a trade route from New Mexico to California). In 1848, the United States government assumed control over the area.” The local tribe within the area is the Las Vegas Paiute Tribe (LVPT), their ancestors were known as the Tudinu (Desert People). -

Farbübersicht Paracord Typ 3 / Microcord

Farbübersicht Paracord Typ 3 / MicroCord schwarz weiss cream dark grey gun grey charcoal grey steel grey silver grey smoke grey foliage foliage green army olive gold tan tan449 mocca olive darb gold-khaki gold brown caramel Farbübersicht Paracord Typ 3 / MicroCord canary ocher yellow lemon neon yellow yellow banana f. s yellow apricot royal orange yellow pastell orange fox orange mustard goldenrod international solar orange neon orange copper red orange imperial red red chili lava red scarled red Farbübersicht Paracord Typ 3 / MicroCord forest green moss sea green leaf green fern green green pepper khaki Dark green emerald green camo green lime mint signal green acid green neon green alpine green kelly green old kelly greenstone army green Farbübersicht Paracord Typ 3 / MicroCord colonial blue baby blue dark baby blue sapphire blue jeans blue pastell blue royal blue caribbean blue bright petrol blue turqoise dark cyan turquoise neon teal navy blue electric blue turquoise greece blue indigo ocean blue midnight blue Farbübersicht Paracord Typ 3 / MicroCord flamingo pink pastel pink rose pink salmon pink sea star pink bubble neon pink passion pink gum pink pastel purple lavender pink fuchsia lilac lavender purple grey royal purple acid purple purple deep purple Farbübersicht Paracord Typ 3 / MicroCord chocolate hazelnut coyote brown rust brown brown acid dark walnut f.s brown new brown II brown chestnut dark burgundy wine brown chocolate crimson. -

Indian Sandpaintings of Southern California

UC Merced Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology Title Indian Sandpaintings of Southern California Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/59b7c0n9 Journal Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology, 9(1) ISSN 0191-3557 Author Cohen, Bill Publication Date 1987-07-01 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Journal of California and Great Basin Antliropology Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 4-34 (1987). Indian Sandpaintings of Southern California BILL COHEN, 746 Westholme Ave., Los Angeles, CA 90024. OANDPAINTINGS created by native south were similar in technique to the more elab ern Californians were sacred cosmological orate versions of the Navajo, they are less maps of the universe used primarily for the well known. This is because the Spanish moral instruction of young participants in a proscribed the religion in which they were psychedelic puberty ceremony. At other used and the modified native culture that times and places, the same constructions followed it was exterminated by the 1860s. could be the focus of other community ritu Southern California sandpaintings are among als, such as burials of cult participants, the rarest examples of aboriginal material ordeals associated with coming of age rites, culture because of the extreme secrecy in or vital elements in secret magical acts of which they were made, the fragility of the vengeance. The "paintings" are more accur materials employed, and the requirement that ately described as circular drawings made on the work be destroyed at the conclusion of the ground with colored earth and seeds, at the ceremony for which it was reproduced. -

Northern Paiute and Western Shoshone Land Use in Northern Nevada: a Class I Ethnographic/Ethnohistoric Overview

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Bureau of Land Management NEVADA NORTHERN PAIUTE AND WESTERN SHOSHONE LAND USE IN NORTHERN NEVADA: A CLASS I ETHNOGRAPHIC/ETHNOHISTORIC OVERVIEW Ginny Bengston CULTURAL RESOURCE SERIES NO. 12 2003 SWCA ENVIROHMENTAL CON..·S:.. .U LTt;NTS . iitew.a,e.El t:ti.r B'i!lt e.a:b ~f l-amd :Nf'arat:1.iern'.~nt N~:¥G~GI Sl$i~-'®'ffl'c~. P,rceP,GJ r.ei l l§y. SWGA.,,En:v,ir.e.m"me'Y-tfol I €on's.wlf.arats NORTHERN PAIUTE AND WESTERN SHOSHONE LAND USE IN NORTHERN NEVADA: A CLASS I ETHNOGRAPHIC/ETHNOHISTORIC OVERVIEW Submitted to BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT Nevada State Office 1340 Financial Boulevard Reno, Nevada 89520-0008 Submitted by SWCA, INC. Environmental Consultants 5370 Kietzke Lane, Suite 205 Reno, Nevada 89511 (775) 826-1700 Prepared by Ginny Bengston SWCA Cultural Resources Report No. 02-551 December 16, 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures ................................................................v List of Tables .................................................................v List of Appendixes ............................................................ vi CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................1 CHAPTER 2. ETHNOGRAPHIC OVERVIEW .....................................4 Northern Paiute ............................................................4 Habitation Patterns .......................................................8 Subsistence .............................................................9 Burial Practices ........................................................11 -

Greater Palm Springs Brochure

ENGLISH Find your oasis. SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA’S LOCATION OASIS Located just two hours east of Los Angeles, Greater Palm Springs is among Southern California’s most prized destinations. It boasts an incomparable collection of seductive luxury hotels, resorts and spas; world-class music and film festivals; and nine different cities each with their own neighborhood feel. Greater Palm Springs serves as the gateway to Joshua Tree National Park. palm springs international airport (PSP) air service Edmonton Calgary Vancouver Bellingham Seattle/ Winnipeg Tacoma Portland Toronto Minneapolis/ Boston St. Paul New York - JFK Newark Salt Lake City Chicago San Francisco ORD Denver Los Angeles PSP Atlanta Phoenix Dallas/Ft. Worth Houston airlines servicing greater palm springs: Air Canada Frontier Alaska Airlines JetBlue Allegiant Air Sun Country American Airlines United Airlines Delta Air Lines WestJet Routes and carriers are subject to change Flair PALM SPRINGS INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT (PSP) Named as one the “Top Ten Stress-Free U.S. Airports” by SmarterTravel.com, Palm Springs International Airport (PSP) welcomes visitors with a friendly, VIP vibe. Airport scores high marks with travelers for quick check-ins and friendly, fast TSA checkpoints, plus the added bonus that PSP is only minutes from plane to baggage to area hotels. AIR SERVICE PARTNERS FROM SAN FRANCISCOC A L I F O R N I A N E V A D A FO U Las Vegas R- HO Grand Canyon U NONSTOP FLIGHTS R FROM CANADA TO PSP D R IV E TH RE E- HO U R D R Flagstaff 5 IV E 15 TW O- HO U R D 40 R IV Santa Barbara -

Morenci Final Restoration Plan with FONSI

Restoration Plan and Environmental Assessment for Natural Resource Damages Settlement, Freeport-McMoRan Morenci Mine September 1, 2017 Prepared by: Arizona Game and Fish Department Arizona Department of Environmental Quality on behalf of the State of Arizona and The United States Fish and Wildlife Service on behalf of the U.S. Department of the Interior Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction ..............................................................................................................................1 1.1 Trustee Responsibilities under CERCLA and the National Environmental Policy Act ........1 1.2 Summary of Settlement ..........................................................................................................2 1.3 Public Involvement ................................................................................................................2 1.4 Responsible Party Involvement ..............................................................................................3 1.5 Administrative Record ..........................................................................................................3 1.6 Document Organization ........................................................................................................3 2.0 Purpose and Need for Restoration .........................................................................................3 2.1 Site Description ..................................................................................................................3 2.2 Summary of -

The Desert Serrano of the Mojave River

The Desert Serrano of the Mojave River Mark Q. Sutton and David D. Earle Abstract century, although he noted the possible survival of The Desert Serrano of the Mojave River, little documented by “perhaps a few individuals merged among other twentieth century ethnographers, are investigated here to help un- groups” (Kroeber 1925:614). In fact, while occupation derstand their relationship with the larger and better known Moun- tain Serrano sociopolitical entity and to illuminate their unique of the Mojave River region by territorially based clan adaptation to the Mojave River and surrounding areas. In this effort communities of the Desert Serrano had ceased before new interpretations of recent and older data sets are employed. 1850, there were survivors of this group who had Kroeber proposed linguistic and cultural relationships between the been born in the desert still living at the close of the inhabitants of the Mojave River, whom he called the Vanyumé, and the Mountain Serrano living along the southern edge of the Mojave nineteenth century, as was later reported by Kroeber Desert, but the nature of those relationships was unclear. New (1959:299; also see Earle 2005:24–26). evidence on the political geography and social organization of this riverine group clarifies that they and the Mountain Serrano belonged to the same ethnic group, although the adaptation of the Desert For these reasons we attempt an “ethnography” of the Serrano was focused on riverine and desert resources. Unlike the Desert Serrano living along the Mojave River so that Mountain Serrano, the Desert Serrano participated in the exchange their place in the cultural milieu of southern Califor- system between California and the Southwest that passed through the territory of the Mojave on the Colorado River and cooperated nia can be better understood and appreciated. -

Plants Used in Basketry by the California Indians

PLANTS USED IN BASKETRY BY THE CALIFORNIA INDIANS BY RUTH EARL MERRILL PLANTS USED IN BASKETRY BY THE CALIFORNIA INDIANS RUTH EARL MERRILL INTRODUCTION In undertaking, as a study in economic botany, a tabulation of all the plants used by the California Indians, I found it advisable to limit myself, for the time being, to a particular form of use of plants. Basketry was chosen on account of the availability of material in the University's Anthropological Museum. Appreciation is due the mem- bers of the departments of Botany and Anthropology for criticism and suggestions, especially to Drs. H. M. Hall and A. L. Kroeber, under whose direction the study was carried out; to Miss Harriet A. Walker of the University Herbarium, and Mr. E. W. Gifford, Asso- ciate Curator of the Museum of Anthropology, without whose interest and cooperation the identification of baskets and basketry materials would have been impossible; and to Dr. H. I. Priestley, of the Ban- croft Library, whose translation of Pedro Fages' Voyages greatly facilitated literary research. Purpose of the sttudy.-There is perhaps no phase of American Indian culture which is better known, at least outside strictly anthro- pological circles, than basketry. Indian baskets are not only concrete, durable, and easily handled, but also beautiful, and may serve a variety of purposes beyond mere ornament in the civilized household. Hence they are to be found in. our homes as well as our museums, and much has been written about the art from both the scientific and the popular standpoints. To these statements, California, where American basketry. -

Native American Settlement to 1969

29 Context: Native American Settlement to 1969 Francisco Patencio outside the roundhouse, c. 1940. Source: Palm Springs Historical Society. FINAL DRAFT – FOR CITY COUNCIL APPROVAL City of Palm Springs Citywide Historic Context Statement & Survey Findings HISTORIC RESOURCES GROUP 30 CONTEXT: NATIVE AMERICAN SETTLEMENT TO 196923 The earliest inhabitants of the Coachella Valley are the Native people known ethnohistorically as the Cahuilla Indians. The Cahuilla territory includes the areas from the San Jacinto Mountains, the San Gorgonia Pass, and the desert regions reaching east to the Colorado River. The Cahuilla language is part of the Takic branch of the Uto-Aztecan language family and all the Cahuilla groups speak a mutually intelligible despite different dialects. The Cahuilla group that inhabited the Palm Springs area are known as the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians. The Cahuilla name for the area that is now Palm Springs is Sec-he, “boiling water,” named for the hot springs located in what is currently the center of the Palm Springs business district. The springs have always provided clean water, bathing, and a connection to the spiritual world, and were used for ceremonial and healing purposes.24 The Cahuilla people refer to themselves as ‘ivi’lyu’atum and are ethnographically divided into two patrilineal moieties: the Wildcats and the Coyotes. Each moiety was further divided into clans which are made up of lineages. Lineages had their own territory and hunting rights within a larger clan territory. There are a number of lineages in the Palm Springs area, which each have religious and political autonomy. Prior to European contact, Cahuilla communities established summer settlements in the palm-lined mountain canyons around the Coachella valley; oral histories and archaeological evidence indicates that they settled in the Tahquitz Canyon at least 5,000 years ago.25 The Cahuilla moved each winter to thatched shelters clustered around the natural mineral hot springs on the valley floor. -

Uniform Newsgram 2019 Winter

A Newsletter keeping you up to date on uniform policy and changes Winter 2019-20 Summer 2019 UNIFORM NEWSGRAM Winter Uniform Wear and News In this issue: NAVADMIN 282/19 - NAVADMIN 282/19 NAVADMIN 282/19 Navy Uniform Policy and Uniform Initiative - Gold Star/Next of Kin Lapel Button Update has been released and provides updates on recent Navy uniform - Black Neck Gaiter Optional Wear policy initiatives. - Optional PRT Swimwear - Acoustic Technician CWO Insignia Gold Star Lapel Button (GSLB)/Next of Kin Lapel - Uniform Initiatives Button (NKLB) Optional Wear - NWU Type III: Know Your Uniform The GSLB and NKLB designated for eligible survivors of - Frequently Asked Questions Service Members who lost their lives under designated circumstances are now - ‘Tis the Season: Authorized Outerwear authorized for optional wear with Service Dress and Full Dress uniforms. - Myth Busted: Navy-issued Safety Boots - NWU Type III Fit Guide Black Neck Gaiter Optional Wear - New Uniform Mandatory Wear Dates NAVADMIN 282/19 authorized the optional wear of a Black Neck Gaiter during extreme cold weather conditions as promulgated by Regional Commanders ashore and as prescribed by commanding officers afloat. When authorized, it may be worn with the following cold weather outer garments only: Cold Weather Parka, NWU Type II/III Parka, Peacoat, Reefer, and All Weather Coat. Optional Physical Readiness Test (PRT) Swimwear Optional wear of full body swimwear is authorized for Sailors who elect to swim during their semi-annual PRT. Optional swimwear will be navy blue or black in color, conservative in design and appearance and must not prohibit the swimmer from swimming freely. -

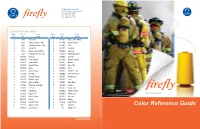

Firefly Color Card

CoatS North ameriCa 3430 Toringdon Way, Suite 301 Charlotte, NC 28277 Tel.: (800) 242 8095 Fax: (800) 843 1105 Color Reference Index Strip Color Color Strip Color Color No. No. Name No. No. Name 1 380 Tan 380 5 341SC Med Dark Navy 5 483 Camo Green 483 5 34158 Sage Green 2 498 Coyote Brown 498 2 412SC Tan 2 499 Tan 499 6 518SC Pewter 1 503 Desert Sand 503 3 589SC Orange 6 504 Foliage Green 504 5 636SX Midnight Blue 3 087SC Yellow 1 756SC Camel 3 088SC Fire Yellow 3 811SC Bright Yellow 4 092SC Patrol Blue 3 832SC Brown 4 093SC Royal Blue 1 833SC Sun Tan 5 094SC Navy 4 837SC Red 5 095SC Dark Navy 2 838SC Golden Fox 2 101SC Kkhaki 2 866SC Tan Air Force 2 105SC Taupe Beige 4 879SC Burgundy 2 147SX Winter Grey 5 880SC Teal 4 155SX Aurora Blue 3 892SC Fire Red 3 162SC Rescue Orange 5 902SC Green 3 163SC Lemon 2 907SC Dark Tan 4 179SX Sky Blue 4 925SC Cherry Red 1 213SC Ligth Tan 1 934SC Khaki #2 100% meta aramid 6 214SC Steel Gray 1 950SC Wheat 6 255SC Olive 6 BLACK Black 3 256SC Punch Red 4 C7316 Light Blue 5 281SC Aquamarine 1 NAT Natural 1 Color Reference Guide 4 340SC Light Navy 1 P1 Khaki P1 Printed in México 201 CNA00-ARAMID Nat 503 756SC 380 P1 213SC 934SC 833SC 105SC Desert Tan Khaki Light Khaki Sun Taupe Natural Sand 503 Camel 380 P1 Tan #2 Tan Beige 100% meta aramid Features Offering 101SC 866SC 147SX 499 498 907SC 412SC 838SC 832SC Tan Winter Tan Coyote Dark Golden Khaki Air Force Grey 499 Brown 498 Tan Tan Fox Brown • 100% inherently fire retardant Sewing Thread Tex Ply • Manufactured to Coats Sewing Thread Specifications 27 2 40 3 • Vertically Integrated supply chain sewing thread is spun by Coats from Fire Retardant staple fiber 60 3 80 4 • High MP 700F for high heat applications 90 4 • Meets NFPA 1951, 1971, 1975, 1977 & 2112 flame 088SC 087SC 162SC 589SC 163SC 811SC 256SC 892SC 925SC retardant standards.